In 2024, Bidzina Ivanishvili stood before a crowd in Gori—the city Russian tanks rolled through in 2008—and said Georgia should apologize to Russia. Not for anything Georgia had done since. For the war itself. The invaded country, he suggested, owed its invader an apology.

How do you get there? How do you build a political system where this statement becomes possible—even applauded? The answer isn't a single law or a stolen election. It's a twelve-year process that amounts to an operating manual for capturing a democracy without firing a shot.

What happened in Georgia from 2012 to 2025 is not random democratic backsliding. It's a playbook for how to capture democratic states without tanks.

Step by step, the ruling party Georgian Dream built what amounts to a "gaslighting machine" at national scale—capturing state institutions that set the agenda and define reality, then activating this machine with laws that invert meaning itself.

The real foreign influence network captured the state, then labeled defenders of democracy as "foreign agents."

Georgia is now not just a struggling democracy; it is the blueprint for contemporary authoritarians on how to take over nations across Eurasia without firing a shot.

Step 1: Secure your oligarch

Every authoritarian playbook needs a linchpin. In Georgia, it is Bidzina Ivanishvili, a billionaire who made his fortune in 1990s Russia during the "gangster capitalist" era of post-Soviet privatization—metals, banking, and a significant stake in Gazprom. He liquidated his Russian holdings for roughly $4 billion, then brought that fortune to Georgia. At his peak, his wealth equaled one-third of the country's GDP.

Georgian Dream was never about pluralism; it was an instrument for cementing oligarchic control.

What looked like philanthropy was elite state capture: Ivanishvili's Cartu Foundation, the nation's largest charity, has spent over $3.2 billion rebuilding theaters, museums, stadiums, even the country's largest cathedral.

The mechanism was clearest in 2018, when Cartu announced debt relief for 600,000 Georgians—17% of registered voters—weeks before a presidential election. Ivanishvili's candidate gained 530,000 votes between rounds.

Unlike Ukraine, where competing oligarchs fragmented power and inadvertently blocked consolidation, Georgia's single-oligarch system enabled autocracy: one hierarchy, one patron, no internal rivals.

Step 2: Win a real election on real grievances

Authoritarian consolidation is easiest when it begins with genuine legitimacy. Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, and they didn't steal the election. No, they won because Georgians had real reasons to vote against Saakashvili, the pro-EU president who came to power during the Rose Revolution.

Two weeks before the election, videos emerged of abuse in Gldani prison. But the anger ran deeper: Saakashvili's "zero tolerance" policies had tripled the prison population, his government had grown heavy-handed, critics were dismissed. Georgian Dream promised a European future and rule of law. They won fairly.

That real victory became a shield. When crackdowns came years later, Georgian Dream could claim: "We represent the people's will." International observers, having certified 2012 as free and fair, extended the benefit of the doubt far longer than warranted. One clean win buys years of credibility to spend down.

This element exports easily. You don't need rigged ballots—you need real grievances and resources to ride them. Across Europe today, populist movements win on genuine failures. The danger isn't the initial victory. It's what gets built afterward.

From Rose Revolution to “Russian Dream”: Georgia at breaking point with pivotal pro-EU protests

Step 3: Eliminate other power centers

After securing legitimacy, eliminate anyone who could become a rival - inside the system or out.

GD began immediately. Within months of taking power in 2012, prosecutors opened cases against virtually every leading figure from Saakashvili's government: his prime minister, defense minister, interior minister, Tbilisi's mayor. Saakashvili himself was convicted in absentia and later imprisoned. An entire political network, decapitated.

Business rivals came next. When banker Mamuka Khazaradze led a $2.5 billion port project, backed by the first Trump Administration, that Ivanishvili opposed, prosecutors suddenly revived decade-old money laundering allegations—also targeting the father of a critical TV channel's owner. Observers compared it to Putin's destruction of Khodorkovsky.

Even loyalists aren't safe. By 2025, GD had turned on its own: former defense ministers, deputy economy ministers, even a longtime Ivanishvili lieutenant under threat. Anyone with independent resources, knowledge, or networks is a potential threat.Unlike Ukraine's competing oligarchs who inadvertently blocked any single figure from consolidating power, Georgia's system was designed for one pyramid. One patron. No rivals.

Step 4: Penetrate and align the security services

If the previous steps built the visible superstructure, this step builds the invisible infrastructure that holds the system together.

Georgia's security services have been reshaped through loyalty-based promotions and expanded domestic surveillance.

The pattern is visible in leadership churn: Grigol Liluashvili, the longest-serving security chief, was replaced by Anri Okhanashvili—who lasted only months before being replaced by Mamuka Mdinaradze, a longtime Ivanishvili loyalist close to PM Kobakhidze. The message to the security apparatus: loyalty to the patron, not the institution.

The targets are broad: protest organizers, political leaders, critics, ambassadors, journalists.

Leaked materials from 2022 proved the State Security Service conducted massive surveillance against opposition figures, the businessman behind Anaklia port, and even the US Ambassador to Georgia. Between October 2024 and October 2025, there were 600 attacks against the press.

This step is decisive because it transforms dissent from a political act into a personal risk. Opposition leaders are jailed selectively, activists face employment pressure and legal threats, journalists face defamation and criminal exposure, ordinary citizens fear being added to the list.

It's further exacerbated by a law creating a centralized mental health database, effective March 2026—a tool ripe for weaponization against dissidents, as authoritarian regimes have done historically.

The "gaslighting machine" now has enforcement power, not just rhetorical power.

Step 5: Capture institutions sequentially

With political and business opponents neutralized, the blueprint moves to formal institutions. In Georgia, this was deliberate, gradual, and sequential:

- First, the judiciary: a documented "clan of judges" controls appointments through the High Council of Justice, ensuring loyalists fill the courts.

- Then constitutional changes: in October 2025, GD filed to ban all three major opposition parties - the entire pro-European bloc - via a Constitutional Court it controls.

- Media follows: Rustavi 2, the last opposition-aligned TV station, was seized through court order in 2019; Imedi TV merged with channels owned by Ivanishvili's son and now runs fully positive coverage of GD versus fully negative for opposition.

- Electoral bodies confirm what the other institutions produce.

When courts declare what's legal, broadcasters declare what's normal, and electoral commissions declare what's valid - reality becomes whatever the system says it is.

“I was not fierce enough”: Georgian activist’s brutal confession as democracy collapses

Step 6: Quiet economic realignment

A captured state needs external anchors. Georgia built three.

Russia: By 2023, Russia accounted for $3.1 billion in combined revenue from remittances, tourism, and exports—about 10% of Georgia's GDP. Russians registered over 30,000 companies. Russian tourists comprised 20% of all visitors, spending up to $1 billion. 97% of Georgia's wheat comes from Russia; 65% of wine exports go there. Direct flights have resumed. The dependency is structural.

China: After GD prosecuted the Georgian-American consortium building Anaklia deep-sea port, a Chinese state consortium won the $2.5 billion contract in 2024. Chinese firms are building Georgia's largest highway and tunnel. Beijing gets 49% of the port that controls the Middle Corridor - the trade route bypassing Russia that the EU desperately needs.

Iran: Nearly 13,000 Iranian companies are registered in Georgia, most to shell addresses—700 at a single Tbilisi building, 800 in a village of 100 people. A Georgian NGO documented links to Iran's Revolutionary Guards. PM Kobakhidze attended the Iranian president's inauguration in 2024.

Trending Now

Economic dependency makes ideological resistance costly.

Resisting Georgian Dream now means risking livelihoods tied to Russian tourism, Chinese infrastructure money, or Iranian trade flows.

Step 7: Turn the machine on—foreign agent laws as reality inversion

After a decade of gradual state capture, the playbook introduces its signature tool: the foreign agents law.

Organizations receiving more than 20% of funding from abroad must register as "agents of foreign influence," submit to intrusive government audits, and face fines or closure for non-compliance. In practice, this means nearly every independent NGO, media outlet, and civic organization in Georgia—the institutions that monitor elections, document abuses, and support democratic participation.

Western analysts often assume this legislation is the opening move in authoritarian consolidation. In Georgia, it came last—and that's the point. When GD adopted its Russian-style law in 2024:

- Courts were already captured to enforce it

- Pro-government media were ready to echo its narratives

- Security services had tools to identify and suppress targets

- Economic dependency had narrowed the space for resistance.

The law isn't primarily about criminalizing NGOs—it's a reality-inversion device. The network built with Russian money and Kremlin connections now frames domestic protesters as "agents of foreign influence." GD accuses pro-European citizens of "endangering national sovereignty"—because instability might "provoke war with Russia."

A country invaded in 2008, occupied ever since, is told that its pro-European citizens are the real threat to sovereignty. Not the occupying power. This is where the machine starts operating: the captured institutions now enforce a constructed reality.

Step 8: Exploit Western distraction

Timing is a strategic resource. The pattern is clearest in when GD chose to escalate.

On 14 May 2024, GD pushed its Foreign Agents Law through a final parliamentary reading amid mass protests and Western warnings—while the West was strained by wars in Ukraine and Israel, with Russia launching a new offensive in Kharkiv.

On 28 November 2024, PM Kobakhidze announced the suspension of EU accession until 2028, while the US was consumed by its presidential transition. Most recently, while the international agenda focused on Ukraine peace negotiations, GD announced a ban on three major opposition parties.

This isn't a lesson about Western failure. The protagonist is GD and its strategy: adopt the most controversial measures when critics are preoccupied. While democratic allies operate on attention cycles, authoritarian consolidation operates on calendars.

Making the new reality believable

The hardest part of the playbook—still incomplete—isn't building the machine but making the new reality feel true. Georgia experienced civil wars and two Russian invasions. That trauma is real. GD exploits it.

Their central propaganda claim: a "Global War Party"— a shadowy coalition of Western governments, Ukrainian leaders, and Georgian opposition—is conspiring to drag Georgia into the Russia-Ukraine conflict as a "second front" against Moscow. In this narrative, pro-European Georgians aren't citizens exercising democratic rights; they're agents of foreign powers trying to provoke war.

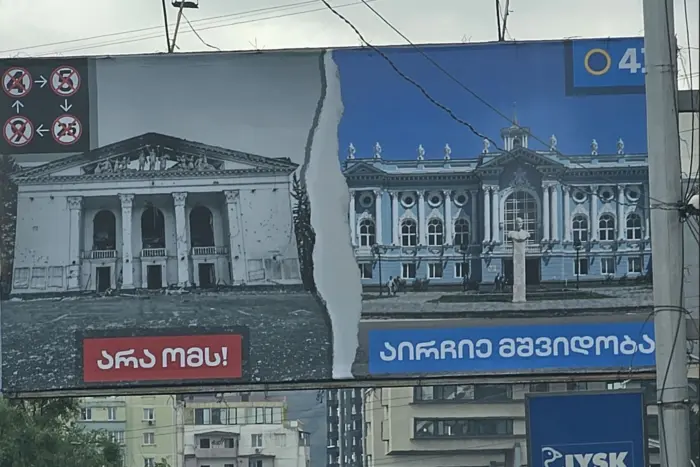

The 2024 election made this explicit. GD plastered billboards across Tbilisi contrasting black-and-white images of bombed Ukrainian cities—including the Mariupol Drama Theatre where 600 civilians died—with color photos of intact Georgian buildings.

The caption: "No to war—Choose peace." The subtext: vote for us or your cities become rubble.

This echoes Viktor Orbán's narrative in Hungary—that Western institutions, not Russia, represent the real threat. But in Georgia it carries particular weight. 20% of Georgia's territory remains under Russian occupation.

The fear is genuine. GD's achievement is redirecting that fear away from the occupier and toward the institutions offering an alternative.

Regional governments, civil servants, and state contractors understand their livelihoods depend on ruling party networks. In towns where the state is the primary employer, opposing GD isn't politics—it's a career decision.

GD reinforces this with Kremlin-style culture war: "traditional family values" versus the "decadent West." This provides cover for those already captured; it rarely converts pro-European Georgians.

In Georgian Dream's constructed reality, the captor—Russia—becomes the protector; the rescuers become enemies.

In GD's constructed reality, Russia—the occupier—becomes a "rational actor" with legitimate interests that must be appeased. Western partners who offered EU membership become "aggressors" dragging Georgia toward war.

The captor becomes the protector; the rescuers become enemies.

Most Georgians reject this inversion. Protests have continued for over a year. But authoritarian systems don't require majority support. They require exhaustion, uncertainty, and fear—and enough captured institutions to make resistance feel futile.

Why the playbook is exportable

This capture sequence is replicable wherever three conditions exist: oligarchic wealth that can accumulate political capital; institutions strong enough to legitimize state power yet vulnerable enough to be captured; and economic dependencies that can be engineered or exploited.

Elements of the Georgian playbook are already spreading.

Kyrgyzstan adopted its own foreign agents law in April 2024—90% copy-pasted from Russian legislation, signed by President Japarov weeks after meeting Putin in Kazan. The crackdown followed the sequence: authorities raided investigative outlet Temirov Live, arrested eleven journalists on charges of "plotting mass unrest," blocked the independent news site Kloop, then passed the law.

Within weeks, longtime rights defender Dinara Oshurahunova shut down her organization rather than register as a "foreign representative."

Serbia submitted its own foreign agents bill in November 2024 - explicitly modeled on Russian and Georgian legislation. President Vučić has already mastered other elements: labeling protesters as "foreign agents," using state media to delegitimize opposition, deploying security services against journalists. The March 2025 protests - Serbia's largest since 2000—show where this trajectory leads, and why it eventually fails to contain genuine popular anger.

Georgia’s Foreign Agents law: Russia’s new frontline in its war against freedom in the world

Russia is not a student of this model but its architect. Moscow refined these techniques domestically before exporting them through aligned oligarchs, shared legal templates, and coordinated timing.

Georgia represents the first complete case study where the full sequence can be observed step by step—from oligarchic capture to semantic reversal—in a country that was, until recently, on a credible path toward European integration.

The lesson is not just what happened in Georgia. It's how quickly the same playbook can be adapted elsewhere.

Georgia should serve as a warning to all vulnerable states. The past decade should be analyzed not as yet another disappointment, but as a prototype for how authoritarian regimes

- subvert democracy without military power;

- invert the meaning of enemy and ally;

- erase the collective memory of occupation and war trauma;

- and try to convince parts of society that defenders of democracy are the ones threatening national sovereignty.

The core question: How do you capture a country using a Kremlin-style playbook? Georgia already knows. Others may soon learn if specific lessons aren't drawn from this case.