A Ukrainian drone struck the Novorossiysk oil terminal on 29 November—and Kazakhstan, 1,500 kilometers away, felt the shockwave. It was the third strike in two weeks. Ukrainian forces had already hit the facility on 14 November and on the night of 24 and 25 November.

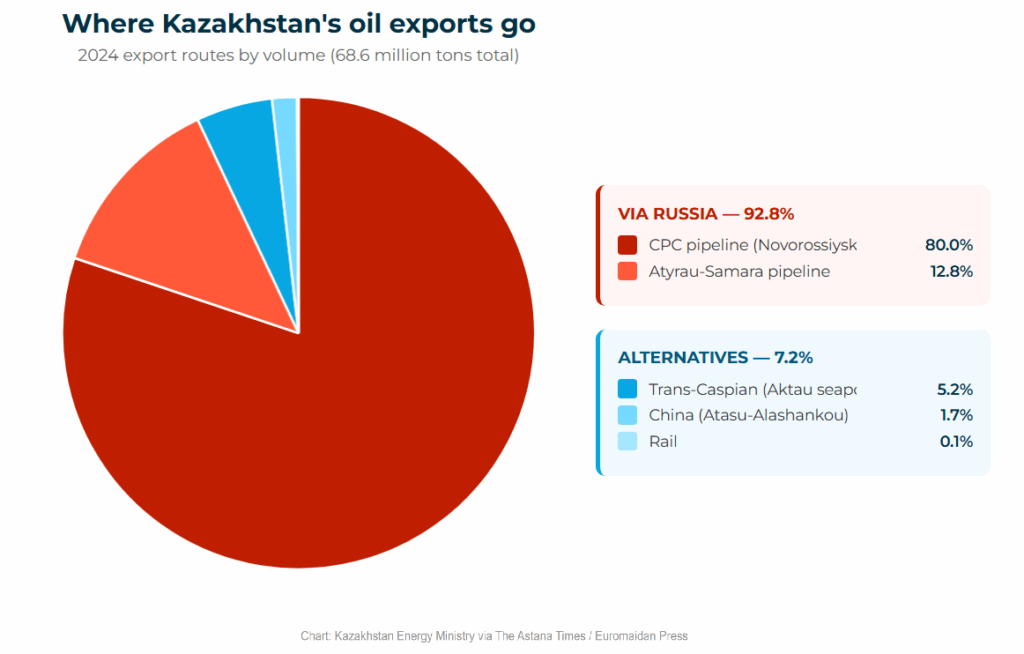

For Kazakhstan, this wasn’t just another episode in Ukraine’s campaign against Russian energy infrastructure. The Caspian Pipeline Consortium terminal at Novorossiysk handles almost 80% of Kazakhstan’s entire crude output.

A single pipeline carries Kazakh oil from the Tengiz field to tankers on the Black Sea.

Oil exports make up 40% of Kazakhstan’s total export revenues, according to the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. The terminal’s continued operation underpins the Kazakh economy.

Astana formally protested what it called “the third act of aggression against an exclusively civilian facility.” Ukraine’s response was blunt: its armed forces are working to “systematically weaken the aggressor’s military-industrial potential.”

An uncomfortable truth

Both claims point to an uncomfortable truth. Kazakh prosperity now depends on infrastructure that Ukraine considers a legitimate military target. Without Novorossiysk, Kazakhstan’s primary export route disappears—and with it, energy security for its third-largest customer: the European Union.

According to Econovis, the EU imports 1.05 million barrels per day of CPC crude, which accounts for roughly 11.5% of all crude imports. Germany remains one of the largest buyers of Kazakh oil despite efforts to cut Russian energy ties. Italy and the Netherlands are similarly exposed. Further disruptions could lead to spiking gas prices and supply shocks as winter approaches.

This vulnerability did not have to happen. It is the result of choices made—and not made—over the course of twelve years.

Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 should have triggered diversification across every nation dependent on Russian energy infrastructure. For Kazakhstan, the math was stark: one pipeline, one port, one point of failure—all controlled by Moscow.

Diversification that never came

Yet diversification never came. Efforts to divert crude to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline date back to 2005, when Kazakhstan’s president attended the BTC inauguration, and Astana agreed to build a connector from its Caspian port at Aktau.

Yet, the project lacked urgency even after the annexation of Crimea. Only after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 did Kazakhstan move in earnest. By then, the window had narrowed considerably.

The EU’s record is no better. Calls to divest from Russian LNG by 2027—thirteen years after Crimea—suggest a Europe still unwilling to acknowledge the threat Russia poses. Kazakhstan has not even released a divestment plan.

Ukraine’s drone campaign against Russian energy infrastructure shows no sign of stopping.

Further strikes on Novorossiysk—or on the pipeline itself—seem likely. For Kazakhstan, the question is no longer whether to diversify, but whether it can happen fast enough to matter.

Too convenient to quit

Even as more oil moves through the BTC pipeline and new routes to China emerge, 2025 is projected to ship more crude via the CPC than 2024—74 million tonnes compared to 63 million tonnes. Alternatives require tankers, transshipment, and complex logistics. The most dangerous route remains the most convenient.

The stakes extend beyond economics.

Kazakhstan has spent three decades balancing between Russia, China, and the West. A prolonged CPC shutdown would force Astana into choices it has long avoided: accommodating Moscow further, pivoting toward Beijing, or seeking emergency Western support.

If Astana does not decide now, the decision will be made for it. For a country that has preserved independence by playing great powers against each other, losing that flexibility could mean decades of dependence.

Twelve years of inaction have left Kazakhstan’s economy at the mercy of a war it did not start and cannot control. The next strike on Novorossiysk could come tomorrow. The time for diversification was 2014. The second-best time is now.

Editor's note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press' editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press