A month of direct war between Europe and Russia would cost roughly €100 billion—about the same as an entire year of current allied support to Ukraine. That calculation sits at the heart of a new report by the Norwegian think tank Corisk, in cooperation with the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, which argues that Europe faces a binary choice: spend significantly more now to help Ukraine win, or spend far more later defending itself.

The findings challenge the prevailing political narrative that Europe cannot afford to increase its support for Ukraine.

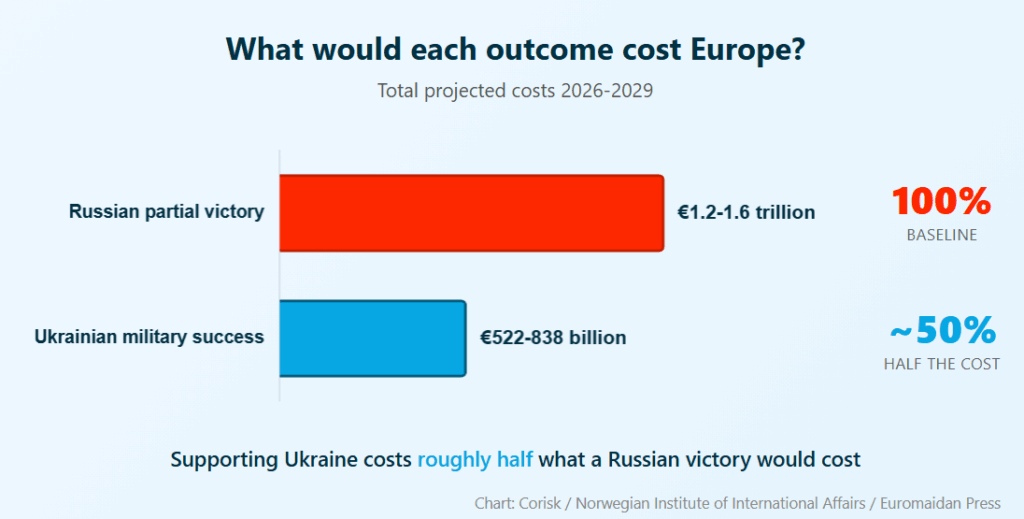

The report arrives as a direct challenge to the Trump administration’s 28-point peace plan, which the authors argue misreads what is required for a stable Ukraine and Europe. Over the course of four years, a Russian partial victory would cost Europe between €1.2 and € 1.6 trillion. Enabling Ukrainian military success would cost €522-838 billion—roughly half.

“This is really a no-brainer,” says Erlend Bjørtvedt, the historian and economist who founded Corisk. “Arming Europe is more expensive than arming Ukraine.”

The math Europe hasn’t done

The report, titled “Europe’s Choice: Military and Economic Scenarios for the War in Ukraine,” and published on 25 November, models what happens if Europe continues current support levels versus what it would cost to equip Ukraine for battlefield success.

Under a Russian partial victory scenario—forces pushing toward the Dnipro River and forcing Ukraine into an unfavorable peace—Europe faces 6-11 million additional Ukrainian refugees costing €150-275 billion annually. Add €256 billion in accelerated rearmament to defend the Baltics and Nordic region, plus ongoing support to a diminished Ukraine.

Under a Ukrainian success scenario, Europe provides an estimated €200 billion annually, Ukraine regains battlefield initiative, Russia accepts negotiations, and some refugees return home.

The €200 billion figure includes compensation for expected US withdrawal from Ukraine support—a factor that looms larger as Washington’s commitment wavers. Current European support sits at roughly €100 billion annually, meaning the continent would need to double its contribution.

“Basically, they will have to have up to €200 billion a year, actually,” Bjørtvedt says. The €140 billion EU loan currently under discussion would not increase support—it would simply maintain existing levels.

That sounds unrealistic. But the alternative math is worse.

Who’s paying and who isn’t

Northern European countries—the Nordics, the Baltics, Poland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK—already provide roughly 95% of European support to Ukraine. Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece contribute little.

“The further European countries are located from Russia, the less money they give to Ukraine,” Bjørtvedt says, citing research from the Stockholm School of Economics.

For countries already contributing, the question isn’t one of capability. Norway alone could significantly increase its support without violating fiscal rules, drawing on oil fund revenues. Germany and the UK have the economic weight to lead.

“Even without [confiscating Russian assets], providing Ukraine with €200 billion per year—that is not even 1% of Europe’s GDP,” Bjørtvedt notes. NATO countries have already pledged to spend 3.5% of GDP on defense. “So, can we then spend 0.9% of GDP on Ukraine? We spent 2% or less on COVID-19 or on saving the Greek economy.”

Frozen Russian central bank assets in Europe total roughly €300 billion. “If we confiscate Russian assets, then it’s absolutely realistic,” Bjørtvedt says.

Europe’s missing strategy

Bjørtvedt’s sharpest criticism targets the European strategy—or the lack thereof.

“Russia has a strategy,” he says. “It was not totally successful. They wanted to take at least half of Ukraine and change the government there. But they have a strategy. They want Ukraine. And we don’t have a strategy. We don’t even know if we want to save Ukraine.”

The Ukrainian government faces constraints too—the constitution prohibits ceding territory, limiting what Kyiv can offer in negotiations. But Bjørtvedt argues Ukraine cannot develop a strategy without knowing what resources Europe will provide.

“If they’re going to have a strategy, they need more money. As of today, Ukrainians can only defend. They cannot afford any other strategy than holding the fort.”

How they crunched the numbers

The methodology matters for skeptical readers. Bjørtvedt’s team collaborated with a colonel from Norway’s War Academy, who conducted the military analysis and attached detailed cost estimates to each equipment category. They used Norwegian military planning tools to verify results.

“The uniqueness of this study is that we go bottom up,” Bjørtvedt explains. “We look at everything that we believe Ukraine would need to succeed, to survive, and more than survive.”

Previous studies by the American Enterprise Institute, the Kiel Institute, and Sweden’s Stockholm School of Economics examined individual countries. Corisk wanted the complete European picture. The Kiel Institute reached the same conclusion for Germany alone: costs would be 10 to 20 times higher under a Russian victory scenario. Corisk found the same ratio applies across Europe.

Trending Now

Russia’s economy: weaker than official figures suggest

One of the report’s core sections tackles whether Russia can sustain the war economically.

For this analysis, Corisk partnered with Olav Slettebø from Statistics Norway, a national accounting expert with nearly two decades of experience who had never studied Russia before. Bjørtvedt sees that as an advantage:

“He came to this as a newcomer but as a very experienced national accountant. He also found that Russia’s economy is probably weaker than the official narrative.”

The key is inflation. Official Russian figures put it at 8-13%. The independent Romir Institute—before Russian authorities shut down its public data earlier this year—estimated 20-42% during the war. The US State Department provided another data point: Russia pays five to six times the world market price for war-critical goods, such as digital components, implying an inflation rate of up to 600% for items essential to weapons production.

When Corisk adjusted Russia’s growth figures to account for higher inflation estimates and incorporated labor participation data, they reached a conclusion that contradicted official narratives.

“We ended up at zero growth in 2023, zero growth in 2024, negative growth in 2025 and 2026,” Bjørtvedt says. “They have been in recession for four consecutive years.”

Evidence of strain mounts: Russia’s largest tank manufacturer, Uralvagonzavod, has begun layoffs; bankruptcies appear even among military production companies; Russia’s pension fund liquid reserves may be depleted by 2026. International bond markets price in a 100% risk of Russian sovereign default based on credit default swap rates—a financial metric indicating investors see default as virtually certain.

But economic collapse doesn’t necessarily stop wars.

“Look at Germany in 1944,” Bjørtvedt says. “There was hardly one house standing. Everything was totally destroyed. But the army was still fighting. The last thing that ended was the fighting.”

His point: economics determines who wins wars of attrition—and Russia’s GDP before the invasion was roughly ten times Ukraine’s. Without increased support, Ukraine cannot outlast Russia, regardless of how much Russia’s economy struggles.

Can Russian data be trusted?

The Corisk team reconstructed Russia’s foreign trade entirely from records of its trading partners. Their finding: Russian trade data is surprisingly accurate.

“We have verified that the international trade data of the Bank of Russia are probably totally correct,” Bjørtvedt says. “We’ve presented this at various international seminars.”

Production statistics from Rosstat, Russia’s statistical office, also appear reliable according to researchers at the Bank of Finland. The problem is inflation—manipulate that number, and everything else looks better than it really is.

The report concludes Russia faces what economists call crowding out: military production, largely state-owned, squeezes private businesses. High interest rates—the central bank rate recently sat at 16-17%—crush civilian industry. Labor shortages intensify as young professionals flee and military recruitment pulls workers from productive sectors.

The political question

Whether European governments will act on this math remains uncertain. The report positions itself as a corrective to both over-optimism about Russia’s collapse and defeatism about Ukraine’s prospects. Russia’s economy is struggling, but won’t implode on its own timeline. Ukraine can regain battlefield initiative—but only with dramatically increased support. Europe can afford that support—but only if it decides to.

“The support that we provide Ukraine today per year—almost €100 billion—that would be the cost of war per month for Europe,” Bjørtvedt says.

The question is political will—and whether Europe will develop a strategy before events force one upon it.