Belgium blocked the EU's €193 billion plan to fund Ukraine with frozen Russian assets at the October 23-24 Brussels summit, demanding legally binding guarantees from other member states before moving forward.

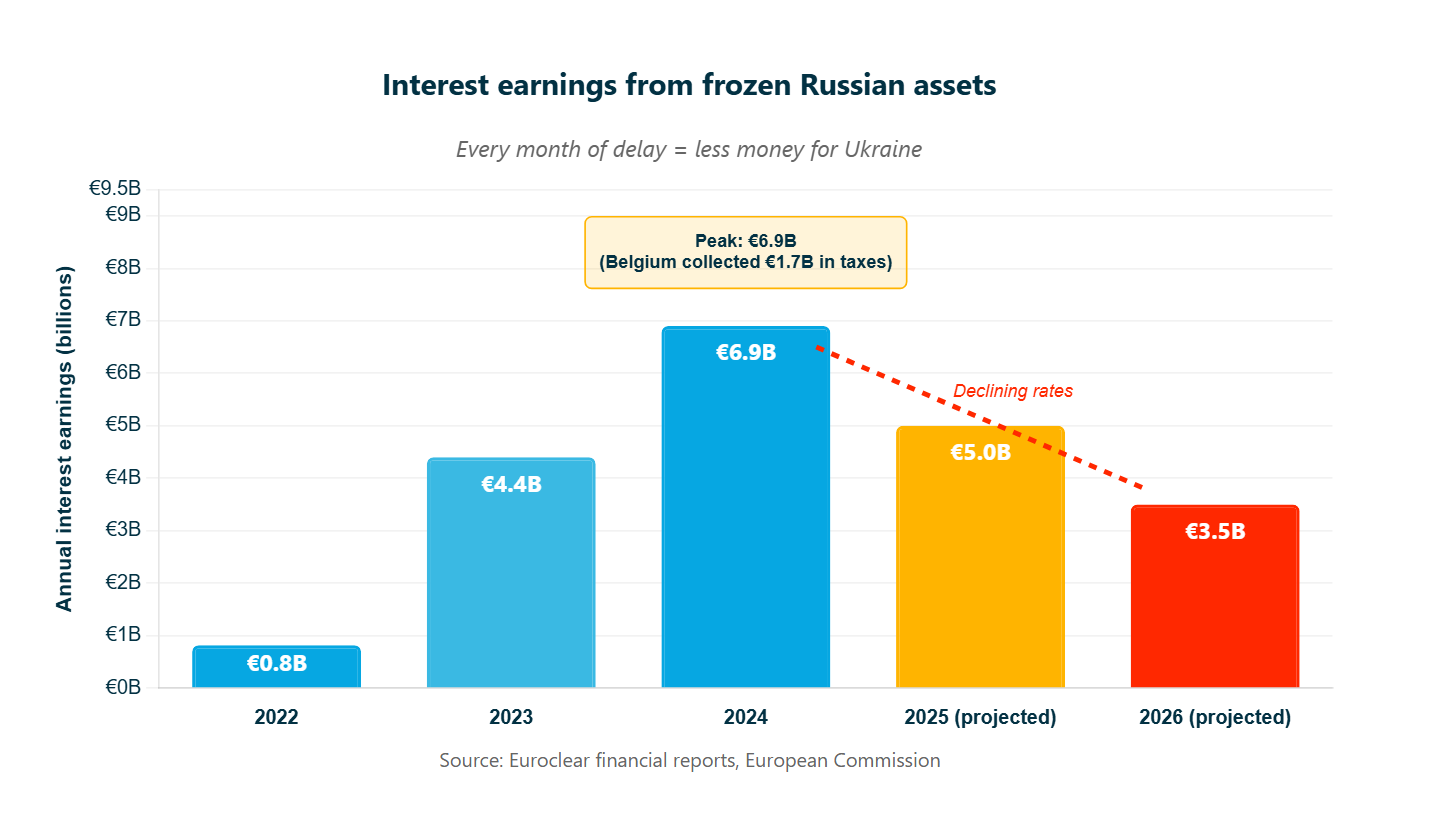

The holdup isn't just postponing help—it's watching that help evaporate. Falling interest rates mean those frozen assets will likely generate €5 billion ($5.8 billion) in 2025, down from €6.9 billion ($8 billion) last year.

The interest matters because it's what Ukraine can actually access. Europe froze the €193 billion principal but won't seize it outright—citing legal barriers and fears of setting dangerous precedents. Instead, the interest earnings from that frozen money have been flowing to Ukraine through the existing G7 loan program.

Belgium's blocking the next step: a proposed €140 billion loan mechanism that would use the principal as collateral, unlocking far more than the dwindling annual interest can provide.

By the time Europe agrees on a mechanism—if it ever does—there might not be much left.

The delay matters because Belgium has skin in the game. The Belgian government collected €1.7 billion in corporate taxes from Euroclear's earnings on frozen Russian assets in 2024 alone—taxes Belgium controls and decides how to spend on Ukraine. Under the proposed EU loan mechanism, earnings would flow directly to Ukraine through EU frameworks. Belgium would lose both the revenue and the leverage.

Euroclear, the Brussels company holding most of Europe’s frozen Russian assets, reported €3.9 ($4.5) billion in interest earnings through September 2025. Falling European interest rates are the culprit, and Euroclear warns the decline will continue as central banks cut further.

Translation: Every month the EU spends arguing means less money reaches Ukraine’s defense. And that’s assuming they ever agree at all.

The money keeps shrinking

When interest rates climbed in 2022, those frozen assets earned just €821 ($952) million. By 2023, they earned €4.4 ($5.1) billion; in 2024, they earned €6.9 ($8) billion.

That peak already passed. This year’s €3.9 ($4.5) billion through three quarters means the annual total will fall well short of last year—possibly to €5 ($5.8) billion or less.

Central banks are cutting rates across Europe, directly reducing what frozen Russian cash can earn.

According to British economist Timothy Ash, Ukraine needs an estimated $100-150 billion annually to sustain its defense and economy. The existing G7 loan program uses only windfall profits to provide $50 billion. As interest rates fall, even that limited stream is drying up.

Belgium blocked progress at the October 23-24 Brussels summit. EU leaders vowed financial backing for Ukraine but held off on the frozen assets plan, setting a vague December deadline instead.

Belgium’s real objection: control, not just cash

Belgium’s resistance makes sense when you consider what it stands to lose. The Belgian government owns 12.92% of Euroclear—9.85% directly through the Federal Holding and Investment Company and 3.07% through a consortium of seven Belgian institutions.

In 2024 alone, Belgium collected €1.7 ($1.97) billion in corporate taxes from Euroclear’s earnings on frozen Russian assets.

Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever notes that Belgium spends this tax revenue on Ukraine aid.

But that framing misses the point. Under the current system, Belgium collects the taxes and decides how, when, and whether to spend that money on Ukraine—giving Brussels leverage and control. Under the proposed EU loan mechanism, earnings flow directly to Ukraine through the EU framework.

Belgium would lose the revenue and the ability to control it. And there’s no verification of whether Belgium spends the full €1.7 ($1.97) billion on Ukraine, or how much goes to other priorities.

Euroclear’s balance sheet shows €227 ($263) billion in total assets as of September 2025, with €193 ($223.9) billion representing sanctioned Russian holdings. The company processes over €1 ($1.16) quadrillion in transactions annually and reported €1.4 ($1.6) billion in underlying business income for the first nine months of 2025—a 7% year-on-year increase in its core operations.

De Wever demands three conditions before supporting the asset-backed loan: transparency about frozen assets in other EU countries (France holds roughly €19 ($22) billion, Luxembourg €10 ($11.6) billion), legally binding risk-sharing guarantees from all member states, and a solid legal basis for the mechanism.

One country, 27 hostages

Belgium’s obstruction reveals a structural problem in European decision-making. When collective action requires unanimous agreement, any member state can hold the process hostage for national interests. The frozen assets plan needs Belgium because Euroclear holds 86% of Europe’s Russian holdings.

Without Belgium’s cooperation, there is no plan.

Trending Now

This isn’t unique to Belgium. Similar dynamics played out over energy sanctions, military aid packages, and financial support mechanisms throughout the war. Individual countries leveraged their veto power to extract concessions, delay decisions, or water down commitments—all while proclaiming unwavering support for Ukraine.

The gap between rhetoric and action has real costs.

Each month of delay doesn’t just postpone help—it reduces the available help, as falling interest rates steadily diminish what frozen assets can generate.

Euroclear’s risk claims don’t add up

Euroclear reported direct costs of €82 ($95) million from implementing sanctions in the first nine months of 2025, plus €25 ($29) million in lost business income. The company faces 94 legal proceedings in Russian courts seeking to access blocked assets, and Euroclear states, “the probability of unfavorable rulings in Russian courts is high.”

But the transparency problem cuts both ways. Euroclear has contributed around €5 ($5.8) billion to the European Fund for Ukraine, yet it has retained significant profits “as a buffer against current and future risks.”

The company’s Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratio stands at 61%—well above regulatory requirements—suggesting its capital position remains extraordinarily strong despite the claimed risks.

That €107 ($124.4) million in claimed costs and losses looks modest next to €1.7 ($2) billion in taxes Belgium collected, or the €3.9 ($4.5) billion Euroclear earned from frozen assets this year alone.

The gap between promises and actions

EU leaders tasked the European Commission with presenting “options for financial support” for Ukraine’s 2026-2027 needs at the December summit. The watered-down language—agreed by all member states except Hungary—shows Belgium’s success in diluting earlier drafts that would have committed to the €140 ($162.8) billion reparation loan.

Poland’s Prime Minister Donald Tusk insisted December must be the “final deadline” for a decision. Germany’s Chancellor Friedrich Merz backed the loan as necessary to prevent Berlin from shouldering Europe’s Ukraine costs alone.

However, the mechanism could not function without Belgium’s cooperation.

The situation exposes how individual national interests can derail collective commitments, even with enormous stakes. Europe’s leaders can debate how to structure the loans, who bears the risk, and how to compensate Belgium. But while they talk, the window of opportunity is closing. The clock is ticking, and with every month of delay, there’s less money to argue about.