On a cold October morning in 2024, Ukrainian soldiers found a lone survivor in a trench near Spirne, a small village in eastern Ukraine. The man was wearing a bizarre contraption made of tourist sleeping mats sewn together - a desperate attempt at protective gear that looked more like a child's cartoon costume than military equipment. This was Li Won Chol, once celebrated as a hero of what Russia called its Russian Spring in Ukraine, now the only survivor of yet another futile assault ordered by his Russian commanders.

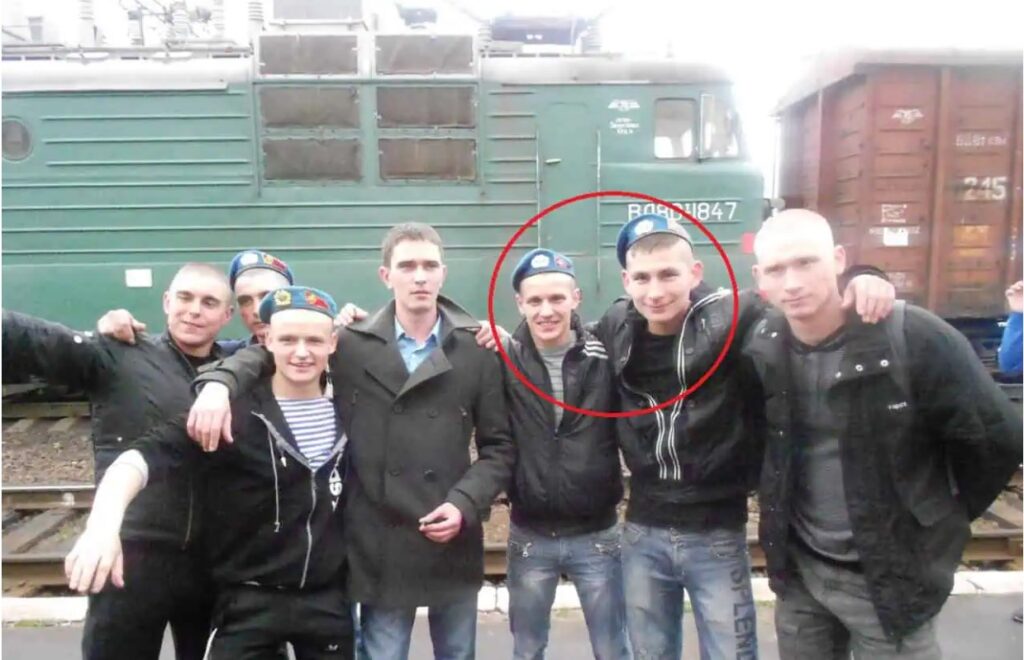

A decade earlier, in March 2014, this same man had climbed to the roof of the Luhansk Regional State Administration building in eastern Ukraine, where he and four others - most of them Russian citizens who had arrived specifically for this operation - raised the Russian flag in what would become one of the first acts of Russia's creeping invasion. Then known as Herman Prokopiv, this ethnic Korean citizen of Ukraine would soon become the first individual to face European Union personal sanctions - a distinction earned even before the EU sanctioned the Russian-backed separatist entity - Luhansk People's Republic (LNR) - he helped create.

The arc of Li Won Chol's story mirrors the broader trajectory of Russia's war against Ukraine. What began in 2014 with local collaborators helping to create a façade of popular uprising would eventually reveal its true nature: a brutal Russian military invasion. When Moscow launched its full-scale assault in 2022, Li Won Chol found himself helping capture the very Ukrainian cities he had once sworn to protect as a Ukrainian serviceman - Rubizhne, Sievierodonetsk, and Lysychansk fell one by one.

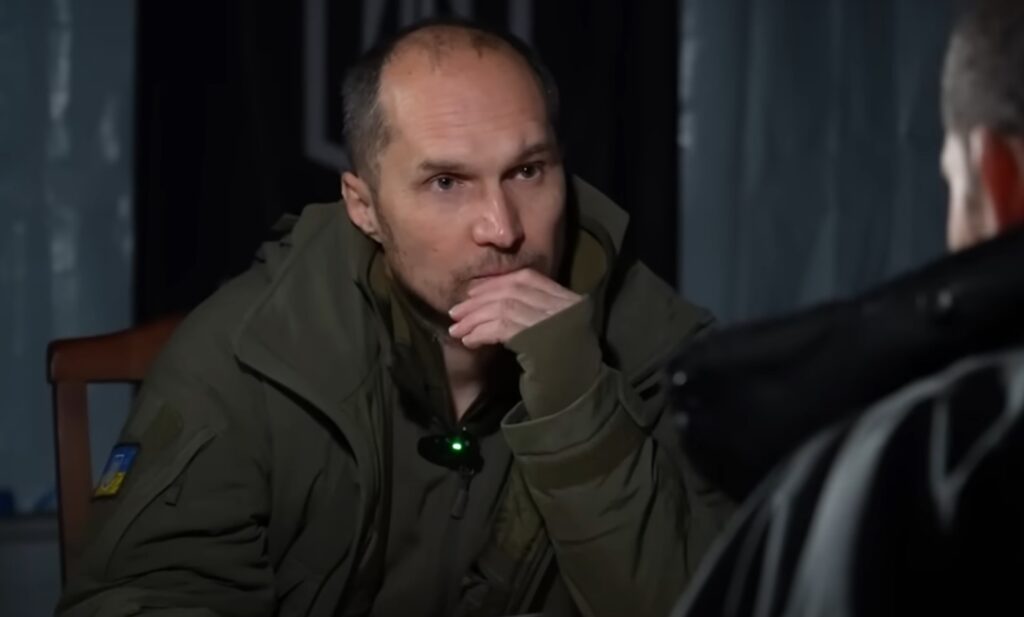

But Russia has little use for its spent pawns. Today, the "heroes" of 2014, like Li Won Chol, are forgotten by Russian propaganda, their stories buried alongside the thousands who died in this war. Yet in a revealing interview with prominent Ukrainian military journalist Yurii Butusov, Li Won Chol's account offers a rare glimpse into how Russia manipulated local collaborators to lay the groundwork for invasion, only to discard them in waves of futile attacks once their propaganda value was exhausted.

"Friends from Russia" in Luhansk

In the spring of 2014, as Russia was testing its hybrid warfare tactics in eastern Ukraine, Li Won Chol was making connections that would alter the course of his life. "These were guys from Russia we met on social media," he tells Butusov with an affected casualness that seems to mask deeper implications. "They asked about the situation. I invited them to visit, so they came." The invitation would prove fateful - not just for him but for the entire region.

The operation to seize control of Luhansk followed a carefully orchestrated script that would soon become familiar across eastern Ukraine. First came the propaganda and protests, then the seizure of government buildings, and finally - crucially - the acquisition of weapons. When Butusov presses him about the source of their arsenal, Li Won Chol's carefully constructed narrative begins to fray.

"It was all from captured Security Service and Interior Ministry storage facilities," he insists initially, his voice carrying the practiced tone of an explanation repeated many times. The claim is absurd on its face - these administrative buildings couldn't possibly house the tanks, mortars, and heavy artillery that his unit would soon deploy against Ukrainian forces. When confronted with photographs of tanks and grenade launchers his unit possessed - weapons that could only have come from Russia - his story shifts. "In 2020, this was already being issued in the army when they created the People's Militia," he offers before retreating behind a final, telling defense: "But how would a simple soldier know?""

Even when shown video evidence of himself commanding a mortar unit shelling the Luhansk airport in June 2014, he maintains the fiction: "Commanders got the weapons. They brought the weapons and asked who knows how to use them." The obvious question - where could local "commanders" acquire military-grade mortars just months after the uprising began - hangs unanswered in the air.

"People's militia" in Luhansk gets Russian commanders

As the conflict evolved from staged protests to military operations, the facade of a "people's militia" quickly gave way to revealing the Russian military chain of command. Li Won Chol's brigade found itself under the command of Denis Ivanov, a Russian officer who went by the callsign Tashkent. The reconnaissance company was led by another Russian, Baur Saitov, known as Zhuk.

When Butusov points out this pattern of Russian command, Li Won Chol attempts a defense that dissolves mid-sentence: "We have local people from Luhansk in our units too, it's based on merit..." He pauses, then nods when Butusov states the obvious: "Not a single brigade commander is from Luhansk Oblast. All high-level officers are Russian."" His quiet "Well, yes" is an admission of what he can no longer deny.

The true nature of this Russian control became brutally clear in the fate of Alexander Bednov, one of the early local commanders known as Batman. When first asked about Bednov's death, Li Won Chol attempts to maintain the official fiction: "They hit some mine, I think." But when Butusov mentions the video evidence of Wagner Group mercenaries executing Bednov on the outskirts of Luhansk in 2015, the pretense crumbles.

"Possibly, it was due to a conflict with Plotnitsky," he admits, referring to the Russian-installed head of the self-proclaimed republic. "He got into politics" - in other words, he had overstepped the boundaries set by his Russian masters.

"We had no mortars": a story that changes with each video

Li Won Chol's account of his combat activities is full of contradictions and attempts to avoid responsibility. In June 2014, he commanded a mortar unit that shelled Luhansk Airport, defended by Ukrainian paratroopers - his former brothers-in-arms. When Butusov points this out, he first denies having mortars: "We had no mortars." Then, when shown a video, he changes his story: "I can't know about this, I wasn't in those storage facilities." Finally, he admits he was "more of an instructor" for the mortar unit.

Particularly revealing is his social media post from 13 June 2014, where he boasted about killing 15 Ukrainian soldiers and wounding 40 more. When questioned about this, he backpedals: "This was part of information warfare, propaganda. How could I know? We were shooting the old-fashioned way - over, under, over."

A hero no more: running from his own Russian world

After Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022, Li Won Chol participated in capturing several Ukrainian cities but was horrified by the losses: "I think we lost about half the brigade in infantry battles and assaults." He cites "lack of experience in command, absence of communication between units," and poor brigade training as reasons. "Our own forces opened fire on me personally about six times," he recalls.

When confronted about the destruction his forces brought to these cities, where the majority of buildings now lie in ruins, his justification rings hollow: "I saw it, but again, this is war. Ukrainian servicemen also hit us with artillery." He seems unable to acknowledge that it was Russia that brought this war to these Ukrainian cities. "We didn't shoot civilians, we didn't loot, we didn't marauder," he insists as if the widespread destruction of civilian infrastructure somehow wasn't a war crime in itself.

The catastrophic losses and senseless assaults finally led him to desert. For a year and a half, the former "hero of the Russian Spring" was hiding in Luhansk - the same city where he once removed Ukrainian flags. He worked illegally at construction sites where no documents were required."Heroes of the Russian Spring are afraid of Russian authorities in Luhansk. After 8 years. What a paradox," Butusov notes ironically.

Eventually, he was found. The arrest was brutal: "They beat me during detention. Not severely, but it was a rough reception. They didn't let me give my wife the keys; she was left at 10 PM with a child at the door," he recounts."I was with a stroller, with a child, they asked if I was so-and-so? I said yes. I asked for their documents, they twisted my arms."

A suicide mission in tourist mats

The most striking part of Li Won Chol's story is his last battle, which appears to have been designed as a suicide mission. The Russian command equipped soldiers with bizarre homemade "armor" made from tourist sleeping mats: "It's like walking in a barrel. Like in a stupid cartoon where a person puts on a barrel and thinks nobody can see them," he describes. The construction consisted of foam sleeping mats rolled into cylinders and sewn together with camouflage netting.

They were given minimal ammunition - only 90 rounds - and basic supplies: "A backpack with a water bottle and a can of canned meat." When Butusov expresses surprise at such light equipment for an assault mission, Li Won Chol admits they understood it was probably a one-way mission.

Among those sent on this suicide mission was his childhood friend, Oleksii "Lyosha" Tytarenko, who had also previously deserted. The assault group was supposed to be guided by a drone to their position, about five kilometers through open terrain. At dawn, the drone operators abandoned them in a sparse tree line despite Li Won Chol's warnings about their exposure.

What followed was a desperate attempt to survive under constant Ukrainian drone attacks. After the first explosion, Li Won Chol and Tytarenko had to cut themselves out of their mat "armor" and try to escape. Tytarenko was wounded and found a small dugout covered with branches. "Come with me," Li Won Chol urged him. "We need to hide, we need cover." But Tytarenko said he'd been hit badly in the back and would stay.

Li Won Chol found a trench covered with planks, but reaching it was difficult as a Ukrainian drone was hunting him. The Russian drone operator, callsign Zhadny (Greedy), who had briefed them before the mission, returned with a new drone and joked about Li Won Chol's desperate attempts to find cover: "Why are you running around, just jump in the trench."

After reaching the trench, Li Won Chol lost all radio contact. He was alone, without water or food, as they had dropped their backpacks while running from Ukrainian drones. The position was littered with corpses of previous assault groups from the 123rd Brigade. After being hit by an FPV drone, he lost consciousness. When he came to at night, Ukrainian soldiers found him and offered him the chance to surrender, which he accepted.

When Ukraine shows mercy

Throughout this conversation, Li Won Chol continually attempts to minimize his historical role. "You greatly exaggerate my significance," he insists repeatedly." Yet his story is remarkable not just for what he did but for what he survived: the violent chaos of 2014, the elimination of fellow separatist leaders by Wagner mercenaries, the meat grinder of the full-scale invasion, and finally, the suicide mission from which he emerged as the sole survivor.

He takes pride in claiming he "wasn't afraid to speak his mind" either under Ukrainian or Russian rule. Yet when ordered on a one-way assault wearing tourist mats as armor, he went without protest. When Butusov points out this contradiction, asking why he didn't fight to the end for his Russian world, Li Won Chol responds without irony: "But I did fight to the end." The end, it seems, was not dying uselessly in a field littered with corpses of previous assault groups.

When asked what exactly he wanted to change in 2014 and what drove him to help bring Russia into Luhansk, his answer is tellingly vague: "That it would be like in Moscow." But when Butusov presses him on whether Luhansk achieved this dream, he admits: "It differs quite significantly." Each time he attempts to construct a narrative that would justify his choices, photographs and videos force him back to uncomfortable truths.

"It was youthful maximalism," he offers at one point, attempting to dismiss a decade of conscious choices as mere revolutionary romance. But this explanation rings hollow for a man who continued serving in the Russian military years after watching it systematically eliminate his fellow "heroes of the Russian Spring," who returned to duty even after seeing half his brigade destroyed in senseless assaults.

Now, after a Ukrainian court has sentenced him to eight years in prison for treason, Li Won Chol finds himself in a final irony: his life was saved by the very Ukrainian forces he helped Russia fight against. The soldiers who found him in that trench could have easily left him there, another nameless casualty in a senseless assault. Instead, they offered him the chance to surrender – an opportunity for survival that his Russian commanders never intended to give him.

His story stands as a testament to the true nature of Russia's war in Ukraine – a campaign built on lies that consumes even its most devoted servants. In the end, Li Won Chol's journey from raising the Russian flag to surrendering to Ukrainian forces while wearing homemade foam armor serves as a stark warning: those who help bring Russian "liberation" often end up as its most disposable victims.

Read more:

- Ukraine court sentences militant of LNR terrorist organization to 10 years

- The traitors, terrorists, and criminals Ukraine received in prisoner swaps with Russia's “LNR/DNR”

- Surviving the “DNR/LNR”. Photo project reveals the horror of captivity

- “Our men are rotting alive!”- say wives of Ukrainian POWs held in “DNR/LNR”