Nobody expected war in the small Russian town Sudzha, even after two and a half years of intense military action raging ten kilometers away. Sudhza is a ten-minute drive from the Russian-Ukrainian border, but “war” is not part of the vocabulary here. All residents interviewed by Euromaidan Press looked baffled when asked about a “war.”

Instead, they talked about the “SVO” (“special military operation”), an euphemism for Russia's 2022 full-blown invasion of Ukraine. The "SVO," along with Russia's proclaimed goals of "denazification" and "demilitarization" of Ukraine, are prime examples of Orwellian lingo, a Soviet language inherited by Putin’s Russia. Its goal is to distort reality, manipulate truth, and promote authoritarian control by using euphemisms and contradictions. Obscuring meaning is a signature move.

For Russians in Sudzha, SVO was happening on a faraway planet. Everyone in Sudzha said they were “shocked” when military activities came to their town. For many, war was peace, in the best tradition of 1984. Oleg, a tanned man with deep furrows on his forehead, in his late 50s, was smoking in front of a temporary shelter—just recently, a school—where he and his neighbors had been hiding for weeks.

He shrugged and said, “We thought the ‘special military operation’ started to rebuild Donbas. We never expected any battles here."

His friend Anatoly, squinting at the sun, added, “We heard something about Mariupol and Bucha but it was all just some news on the TV. Lots of stories, lots of noise.”

Like most Russians, the residents of Sudzha were oblivious to the fact that their military had committed war crimes in Ukraine. The exact number of Ukrainians killed in the seaside city of Mariupol, which fought off a Russian siege for three months, all the time being leveled by Russian aviation, will never be known. However, some estimates place this number as high as 87,000.

In Bucha, occupied between 5-30 March 2022, executions often followed security checks. As of 8 August 2022, 458 bodies had been recovered, including 9 children; of which 419 had weapons wounds.

Window into reality of Russia's war

Although the Russian military destroyed and damaged buildings in Sudzha during six weeks of Ukrainian incursion, Ukrainian troops treated the locals in a polite albeit reserved manner. They provided the residents with food, drinking water, and shelter from the Russian attacks.

On the central square of Sudzha, an empty pedestal loomed, plastered with large photos of collapsed high-rises, ruined schools, and kindergartens in Borodianka, Irpin, and Donbas - the Ukrainian Army's attempt to break through Russia's silence about the war crimes of its army in Ukraine.

"The Russians destroyed the Lenin monument with an FPV drone," Oleksii Dmytrashkivskyi, a spokesman for Ukraine’s military administration in Kursk, explained the pedestal's emptiness.

He and Oleh Palchyk, both servicemen of the Territorial Defense Forces, brought the photo exhibit As Long as the War to Russia. Perhaps symbolically, more photos of destroyed Ukrainian cities were taped to the plywood covering the windows of a temporary shelter.

Residents cut off from communication and TV signals now had a window into the nameless war.

“Speak to them and see for yourself if their mindset is changing,” Vadym Misnik, spokesman for the Ukrainian Siversk tactical-operational group, said, inviting me into a shelter for the locals.

Russian war narratives face reality

Although the locals had few opportunities to view the outdoor exhibits due to relentless Russian military attacks on Sudzha—drones, guided bombs, artillery, and missiles—the perspective seemed to shift for some. A few Russian civilians, chased by FPV drones and forced to sleep in basements, began expressing doubts about their government’s agenda.

Yuliana, a thin and fragile teenager, nervously fumbled with her blonde hair and necklace as she spoke to our crew on the second floor of the shelter. In front of her was a plate of candies, with flies swarming over it. The large hall lined with beds was hot, and the loud rumble of a generator nearly drowned out her voice.

"I knew there was a war, but on the TV, they said Russian soldiers were all good,” she said. “It’s not true, as it never happens this way, and I knew it. People are different. We were told that Russia’s goal was to free Donetsk and Luhansk, but some said that Putin just wanted new lands. It was confusing to me. I want the war to end."

Many remaining Sudzhans seem to be confused. Clinging to habitual Russian state propaganda narratives appears to be comforting.

Lydia, a partially blind woman in her 80s, sat on a bed in the communal room and was reluctant to talk at first. She opened up, though, and spoke about the “special military operation” at length and in classical Russian propaganda narratives.

She knew the war had been going on since 2014 -- the year when Russia occupied Crimea -- and believed that “Ukraine attacked Luhansk" -- the number one Kremlin narrative used to explain the war it had unleashed in Ukraine.

In reality, in 2014, Russia set up a proxy state in Luhansk Oblast, supplying weapons and personnel to fight against Kyiv, up until Russia's full-scale invasion of 2022.

She said that in 2022, “Ukraine wanted to pull Russia into the war with help from America and Europe,” reiterating Kremlin narratives that Russia is a state threatened by the West.

Lydia had warm memories of growing up during Stalin’s era, “when everything was amazing because we were young."

Her nostalgic Soviet memories are unchallenged and even promoted under Putin. As a result, ever-growing numbers of Russians consider Stalin, a Communist dictator responsible for murdering millions, an "effective manager."

This nostalgia, a tool of totalitarian states for exploiting emotions, serves a very practical purpose for the Kremlin as it seeks to resurrect its sphere of influence by invading Ukraine.

Symbols like the Soviet hammer and sickle and unchanged Soviet-era street names like Communist ideologist Karl Marx perpetuate a longing for the past, inhibiting critical thinking while evoking feelings of belonging to a great nation. By manipulating memories and emotions of a bygone era, the Kremlin ramps up support for its imperial foreign policy and repressive actions at home.

Other Sudzha residents are simply confused and feel left behind.

Maria Egorovna, 90, half-deaf, pale, with dark bags under her eyes, sat in the hallway of the school and asked everyone to find her two sons. She was afraid that they could have been killed during the first days of the attack. Maria lost touch with them when she was left alone in her house at the beginning of the Ukrainian incursion in the Kursk Oblast.

“No food, no water, no telephone and under fire,” she said. “I would step out to feed my fifteen chickens, and bombs are falling and falling, so I’d say, ‘Boys, don't bomb me! I don't bomb you, do I?’ But they don't hear me.”

When asked what she thought about the war, Maria Egorovna appeared to be confused, “What can I think about the war when I am 90? I don't know where my sons are. Maybe they are already dead. Why do they shoot? Putin said he wouldn't shoot at people. I do believe Putin because he is independent... unlike Zelenskyy.”

Anatoly, back from the yard, said, "We are sheltering in a basement and I don’t know who is bombing us."

Others had some ideas: Olga, a jolly young woman in her early twenties, wore a ribbon in Ukrainian national colors, yellow and blue, around her wrist, and said that it was clear to her that Sudzha was suffering from Russian bombing.

“It seems to me that about a thousand Russian people are left here without a chance to evacuate,” she said. “I think the Russians are just trying to get rid of those of us who didn't get evacuated. They want to get rid of eyewitnesses. I live far from the city administration building, and I didn’t make it on time to catch the evacuation bus. People nearby made it, but there were only three evacuation buses. My mother was leaving in one of the buses, under fire. I don't know who was shooting at the bus then. I don't think well of Putin anymore. He should have evacuated us.”

Olga lived in Sudzha since 2005, working at an office. She didn't expect there would be a war and didn't hear anything about it. Working long hours, she claimed she had no time to watch TV or listen to the news.

“I did hear about SVO but knew nothing about it. Some men from the village did serve in the army,” she said. “We didn't think anything would happen here. We have only five thousand people and there is nothing to get here. I thought: why would anyone come here? You live in a moment, one day at a time, day by day. Now, there are terrible air attacks and we have to sit out in basements.”

Olga enjoyed being at the shelter.

“Some of us live at home and some come to the shelter for water and food. People are getting ready for winter and digging some potatoes in case there is no food. I know a lot of people and we play games,” she said.

“I try not to step outside because of the drones. Yesterday, a drone was buzzing nearby and then it fell and blew up. The drones often drop something on buildings.”

Olga said that she was influenced by the videos of what was happening in Ukraine and would like to move to Ukraine.

“We were told bad things about Ukrainians but they helped us and didn't do anything bad to us.”

One resident, speaking on the conditions of anonymity for security reasons, said, “Many know the war is about grabbing land and are anti-Putin. But no one will tell you their real thoughts. It’s dangerous. The Russians will be back, and they may kill us.”

Fear is the most powerful weapon for controlling a population that must remain loyal. When this control weakens, the Russian government loses its grip on power--and its interest in the population.

Russian civilians stranded in Sudzha

The Kremlin has assured its citizens for years that the Ukrainian Army had been bombing civilians in Russian-occupied Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts. Now, that narrative has come back to bite, as the Russian authorities failed to evacuate locals in areas now controlled by the Ukrainian army.

This now endangers hundreds of Russian civilians as the Russian Army launches attacks in an attempt to regain Kursk, and reportedly plans a larger offensive.

Misnik, a spokesman for the Ukrainian Siversk tactical-operational group, told Euromaidan Press that the Ukrainian forces compiled lists of Sudzha residents for evacuation, sending them to both Russian and Ukrainian authorities. The Russian authorities failed to respond.

This effectively leaves many civilians stranded in a war zone, "as Russian civilians cannot and will not be evacuated to Ukraine forcefully.”

Passing by the WWII memorial, Misnik said, “Our ancestors were fighting against fascism together and now we are fighting against Russian fascism. We do not remove any of their monuments.” Like many Ukrainians, Misnik acknowledged shared history while resisting the false narrative of "brotherly nations" pushed by the Kremlin.

He pointed at the memorial plaques dedicated to Russian soldiers who fallen in the Chechnya war and a 20-something-year-old soldier killed in 2022 at the beginning of the full-scale aggression.

“Here is the Russian World marching to die for Putin,” he said.

A modern building of a kindergarten and a primary school was intact when the Ukrainian forces took control of Sudzha, but in early September, it was attacked by the Russian military, according to Misnik. Charred parts of a Russian Geran drone, also known as Shahed, were in front of the kindergarten door, and the inside was packed with portraits of Putin and the victorious Soviet and Russian army posters.

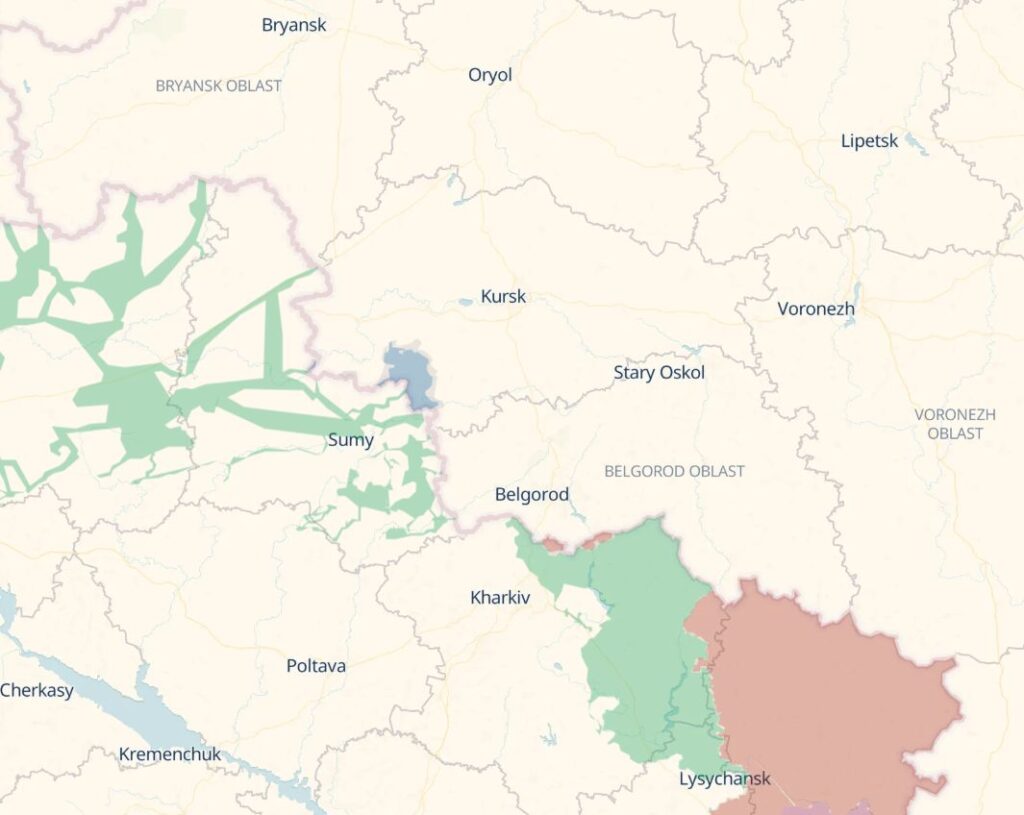

Since 2003, Putin has made "patriotism" the core ideology of Russia, and military victories have become a brand. In Kursk Oblast, where the Ukrainian army occupied 776 km2 within a month, while the Russian authorities abandoned civilians, reality breaks the protective bubble of the Kremlin's illusion. Will the Russians see, hear, and acknowledge the facts?

Related:

- Ukraine deploys demining drones to break Russia’s Dnipro wall

- Russian drones hunt civilians, terrorize Kherson with “human safari”

- Frontline report: Russian forces trapped twice in Kursk as rescue mission backfires

- Kyiv invites international organizations to Kursk amid ongoing military action

- Kursk offensive: “I’m living every soldier’s dream,” says Ukrainian fighter