Not much reminds of the war at shashlychnа—kebab joint—in the Kherson Oblast, apart from the distant booms of artillery mixing with the dusty cat purring on a shabby, Matrix-like couch. The smell of fried meat, delicious smoke, an ice cream stand with Mango-Marakuya and Lavender-Mint syrups for lemonades, and cardboard boxes topped with brilliant-green watermelons make one feel on a summer country outing, but the feeling is deceptive. A walk to the nearby creek or a stroll in a sunflower field can cost you your life.

In 2023, approximately 174,000 square kilometers—one-third of Ukraine’s territory—were contaminated with mines, placing more than 6 million people at risk of injury or death, according to Yuliia Svyrydenko, First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economy of Ukraine.

Even though by February 2024, demining services reduced the area to 156,000 square kilometers, as reported by the State Emergency Service of Ukraine, Ukraine remains the most heavily mined country in the world since World War II.

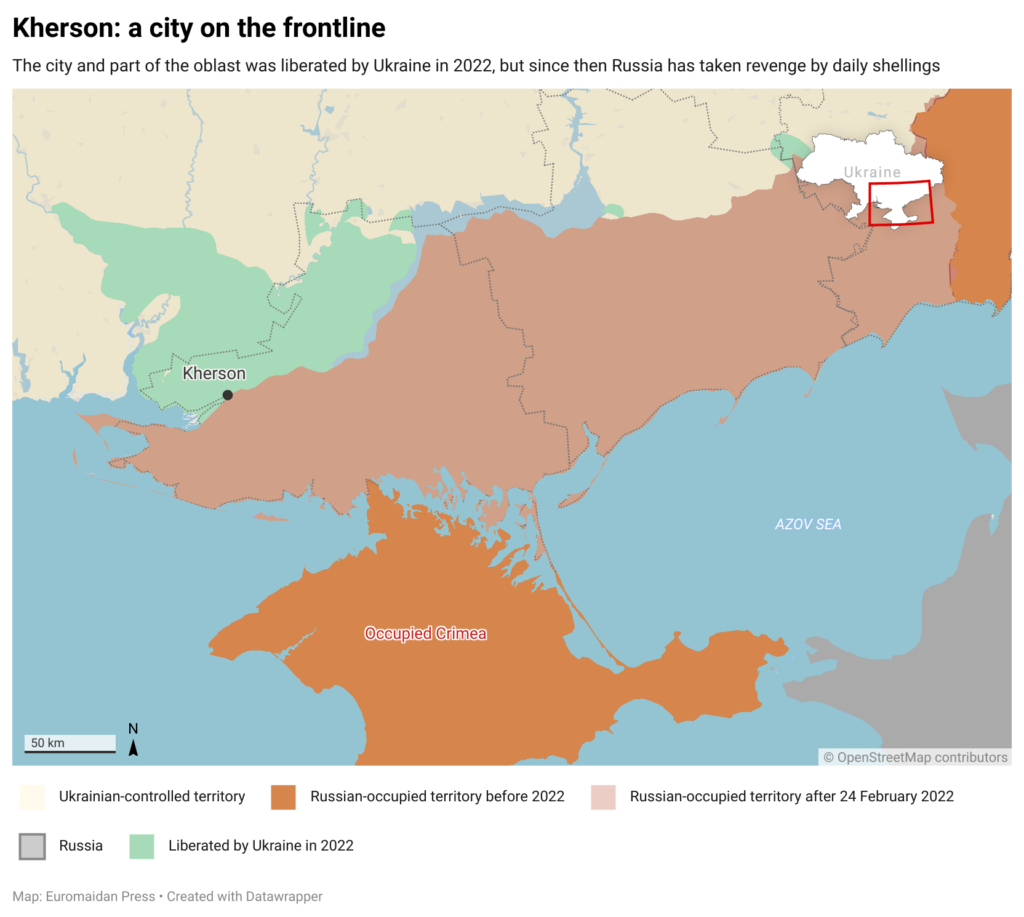

In Kherson Oblast, by the end of 2022, about 50,000 square kilometers of de-occupied land needed demining. According to the local military administration, by March 2024, 40% of agricultural land on the liberated territories of the Kherson Oblast (2060 kilometers (206,000 hectares) were demined,

Yet another 2700 kilometers (270,000 hectares) were potentially contaminated with Russian mines, and unexploded ordnance, reported the authorities in May 2024.

The humanitarian demining process is ongoing and well-covered in the press.

But what about the water mines? Enter drones.

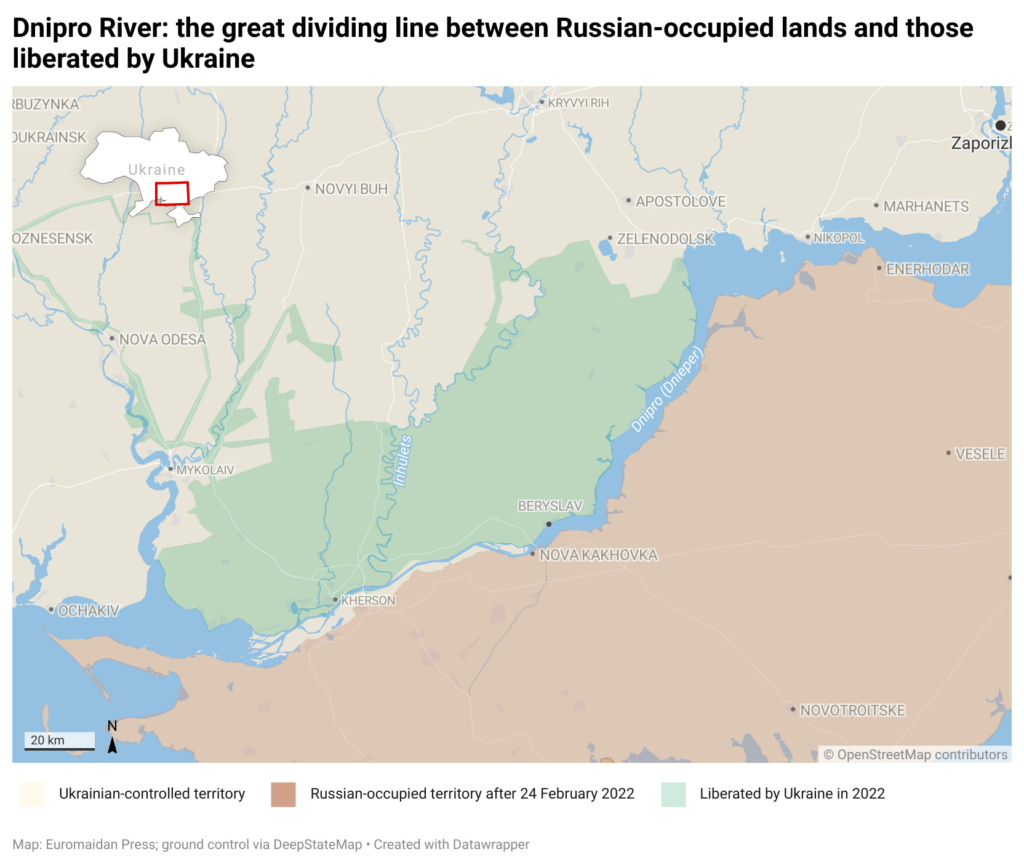

Four fighters of the 126th Independent Brigade of the Territorial Defense Forces of the Ukrainian Armed Forces explain to Euromaidan Press a drone-performed water demining in the Dnipro (Dnieper) River.

They look like The Matrix Resistance Fighters: eyes red, tired and determined, hands rough and calloused, clothes weather-beaten and burned out in the sun but neat and clean.

Sipping strong coffee after an endless shift, they ask not to take photos or reveal their call names. Their work is extremely dangerous. They fly drones to hunt mines. Russians fly drones to hunt them. Our conversation is about the future of warfare: drones, or, possibly, about the future of the world, in which machines control humans.

Water mines in the Dnipro River and vicinity

While water mines in the Dnipro River in the Kherson Oblast do not endanger the civilians—there is no navigation or fishing due to the Russian troops' proximity—they pose a significant threat to Ukrainian forces operating in the contested coastal areas of “gray zones,” as well as on the islands and islets along the river.

The fight for the Dnipro River depends on the sappers as the mines complicate the mission of the Ukrainian troops engaged in ongoing efforts to liberate the Russian-occupied left bank, slowing the advance and endangering personnel and equipment.

Everything is done by drones. Russian drones perform remote mining: the FPV (First Person View) drones drop standard munitions, such as YARM and PDM-4 mines, and sometimes homemade explosives.

YaRM mines, equipped with basic target sensors, are dropped in water reservoirs and anchored to prevent drifting into the Black Sea. They can be positioned on the water surface or occasionally submerged, though the Russians rarely place the mines underwater due to the absence of large ships on the Dnipro River.

The PDM-4 operates on the same principle, but it is a newer model, with explosives at the bottom and an empty top section for buoyancy. Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) are based on the same principles as traditional Soviet and Western mines, which use a combination of explosives and target sensors.

However, in modern warfare, nearly any sensor or power supply paired with an electro-detonator can be used to create a functional mine.

Maritime and riverine demining

To destroy these mines, it is essential to either strike them directly or pass close enough for the target sensor to activate, triggering the detonation and neutralizing the mine. According to the documented standard procedures for demining YaRM ammunition, the technician approaches the object by boat, installs an explosive, leaves, and remotely explodes it.

However, this method cannot be applied in the Dnipro River in the Kherson Oblast due to the proximity and omnipresence of the Russian drones and artillery.

In general, the freshwater demining process is more complex compared to land and maritime demining in the Black Sea.

Land demining is relatively straightforward. Mine detectors locate explosives, and once identified, the mines are typically destroyed through controlled detonation. On land, demining teams can work with precision, and the detection tools are well-established.

Manual land demining involves trained personnel using handheld detectors to methodically sweep the ground for explosives. Machine land demining uses specialized vehicles equipped with flails, rollers, or robotic arms to clear larger areas more efficiently. However, these machines are limited in their ability to navigate uneven or densely vegetated terrain.

Yet, land demining methods do not apply to underwater environments. Water dynamics, such as currents and reduced visibility, make detection and destruction of mines far more challenging.

Hi, I'm Zarina, a frontline reporter for Euromaidan Press and the author of this piece. We aim to shed light on some of the world's most important yet underreported stories. Help us make more articles like this by becoming a Euromaidan Press patron.

In non-combat zones, minesweepers—special-purpose ships used to search and destroy sea mines—are typically employed for maritime and riverine demining. In the Black Sea, sappers manage naval mines, using specialized equipment like sonar and unmanned vehicles for general underwater detection.

However, along the Dnipro River and nearby areas, using boats is currently impossible. The Russian military actively targets and destroys all boats, regardless of their freight or destination, making every vessel a potential target.

"Underwater Javelins," unmanned mine-clearing boats equipped with side-scan sonar and small torpedoes, are suited for wider, deeper sections of the Dnipro River. In many areas along the Dnipro, the narrow, shallow straits are often cluttered with debris, making it difficult for these drones to detect mines effectively. Additionally, launching them requires direct access to the water, which is currently impossible as along the 80-kilometer stretch of coastline west of Kherson on the right bank of the Dnipro, villages lie in ruins, offering no cover for units attempting to approach the river safely.

Drone mine hunters

The task of the two river undermining units, responsible for demining the Dnipro River and its straits, bays, and lakes, is critically important for the battle for the Dnipro River. Covering the area from the Inhulets River to Beryslav City, these units employ aerial drones to locate and neutralize water mines.

Despite the significance of their mission, the sappers have not received formal training for this type of demining, simply because these methods are non-existent. They are developing and adapting devices and approaches on the fly. The art of improvisation is everything.

Each unit is composed of four soldiers: two drone operators, a coordinator managing ammunition, and a driver. Each role is critical to the success—and survival.

The drone operators work in shifts, flying small drones and conducting surveillance to identify potential mines. The operators navigate drones to scan for suspicious objects, which can be challenging to distinguish from debris such as trash, leaves, branches, dead fish, and even bodies of fallen soldiers.

The task demands considerable skill and experience. Operators work 12 hours a day from 5 a.m., often suffering from eye pain due to prolonged monitor use. They lack specialized eye protection and a TV screen connected to the monitor to improve visibility. The monitor’s small screen makes it challenging to detect underwater mines.

Ukrainian drone operators could benefit from AI-integrated software that compiles data and enhances target identification to improve the identification of water mines amidst debris like branches, leaves, and even bodies. So said Michael Montoya, Director of Invictus Global Response, an NGO founded by US and British military veterans with decades of experience, focused on landmine clearance, teaching civilians to identify explosive risks, and providing support in mine action, stockpile reduction, and humanitarian assistance, in an interview with Euromaidan Press.

The coordinator is responsible for preparing the ammunition, a task complicated by the absence of standard explosives for freshwater mine destruction in the Ukrainian army. The process involves several stages: 3D printing, utilizing regular explosives like TNT, and assembling the ammunition on-site. Typically, the unit might receive 5 kg of explosives intended to destroy 5 mines, but this allocation often proves insufficient, as a single target may be missed, leading to the failure to detonate.

The detonation operation is often a lottery. The precision of the strike is the key.

The units lose drones daily—sometimes several in a single day—primarily due to Russian electronic warfare (EW), and occasionally to direct fire.

Michael Montoya said that to reduce signal vulnerability and improve the resilience of Ukrainian drones against Russian EW systems, increasing the power and direct transmission could help but may compromise other functions. While tethered systems offer security, he explained, they could reveal the operator’s location, and direct line-of-sight communication might expose the operator to potential threats.

According to Montoya, incorporating frequency-hopping technology into drone demining operations could help navigate different frequencies under electronic warfare attacks, allowing drones to maintain connectivity. Deploying a GPS-guided drone to gather data on active frequencies, return with that information, and send out another drone to disrupt those frequencies could be an effective tactic to reduce Ukrainian drone losses and counter Russian surveillance drones.

The driver’s role is hard to overestimate: he is responsible for safely transporting the team to and from their location under the non-stop attacks.

The coastal area is under Ukrainian Army control, but the islands and isles in the Dnipro River remain a “gray zone” with both Russian and Ukrainian troops present. The Russian forces have their own drone units and surveillance capabilities, targeting specific sections of the Beryslav highway and able to spot the unit’s vehicle at any moment.

The omnipresent surveillance of sci-fi is here: every move is tracked and recorded by drones. Drones appear out of thin air, searching for targets around the clock and striking without warning—on a “search and kill” mission.

Russians conduct reconnaissance using larger Orlan drones as well as Mavic drones, often deployed in a "carousel" pattern, returning for recharging to the operators while continuously monitoring the area. There are night-vision and thermal vision models so there is an ever-present “eyes” in the skies.

Once located, the adversary attacks. The strike could come from mortars or FPV drones capable of reaching a speed of up to 145 km/h. The driver must race at high speeds to evade the fast-moving threats. The situation has deteriorated significantly; while the highway was relatively safe until September 2023, by August 2024, few vehicles dared to travel there.

The omnipresent surveillance of sci-fi is here: every move is tracked and recorded by drones. Drones appear out of thin air, searching for targets around the clock and striking without warning—on a “search and kill” mission.

Defense against drones is one of the most vulnerable parts of this story. Electronic warfare (EW) controls the skies in modern warfare, with both sides constantly trying to manipulate frequencies and signals in an invisible battle. The EW systems installed on the sappers’ vehicles provide some level of reassurance but not a perfect solution. In a game of hide-and-seek, Russian drone operators constantly switch frequencies, reducing the effectiveness of these systems.

Despite the fatigue from over two years of service, daily losses of drones to electronic interference, and direct attacks, the soldiers' morale remains high. The comradery spirit of the resistance is palpable, and as the unit bids goodbye, leaving the short-lived vacation from the fight, their faces are lit and their gait is firm.

***

The Matrix does come to mind again, whether one likes dystopian thrillers or not. Not only do drones shape the battlefield, but the battle of human will against technological supremacy is real.

The war is developing dynamically. Technologies are advancing. AI is another unexplored chapter of this war. The reliance on drone warfare creates a new reality for modern combat in which continual innovation and adaptation are a must for survival. Ukrainian soldiers face the challenge of outwitting enemy drones, and the drone demining units operating on the Dnipro River serve as a prime example of ingenuity in modern warfare.

Sci-fi aside, there is an urgent need for more advanced resources and equipment from Western allies, with the emphasis on Mavic drones, batteries, TV screens for monitors, standard ammunition-enhanced electronic warfare units, and regular updates to adapt to evolving threats, to keep pace with a better-equipped adversary.

A previous version of this article had the headline "Ukraine deploys drones to demine Dnipro river for major offensive"

Related:

- Russian drones hunt civilians, terrorize Kherson with “human safari”

- Chasiv Yar’s survival rests on daring night drone team

- Ukraine now has drones rescuing fallen drones from hazardous battlefields

- Firefighting robot certified for Ukrainian military for dangerous demining missions