Recent archaeological developments in Ukraine are rewriting the history of early urbanization. Massive planned settlements, dating back to 4000 BCE, challenge the long-held belief that the first cities emerged in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, and parts of Iran, Türkiye, Syria, and Kuwait.

As published in the Swiss Neue Zürcher Zeitung, new archeological research suggests that the first urban settlements in present-day Ukraine are much older than previously assumed.

These so-called Megasites (from the Greek word “mega” for something large and from the English word “site,” which refers to an archaeological site) reveal complex societies that flourished for centuries before disappearing around 3600 BCE.

Their existence not only pushes back the timeline of urban development, but also sparks heated debates about early social organization, sustainability, and the very definition of a city.

Key points:

- Discovery: Found in the 1960s through aerial photography and confirmed by geomagnetic surveys

- Age: Dated to around 4000 BCE, predating Mesopotamian cities by centuries

- Size: Ranging from 30 to 320 hectares, with the largest comparable to Monaco

- Layout: Planned settlements with houses arranged in concentric rings

- Culture: Part of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, known for distinctive pottery

- Duration: Each settlement lasted about 200 years, with the phenomenon persisting for 500 years

- Decline: Disappeared around 3600 BCE for reasons still debated

For decades, archaeologists believed that the first cities in human history emerged around 3800 BCE in Mesopotamia, in what is now Iraq. These early urban centers were characterized by thousands of people living in close proximity, sustained by food produced in the surrounding hinterland, engaged in trade, and governed by a complex administration.

However, recent archaeological discoveries are challenging this long-held belief. In Ukraine, researchers have uncovered evidence of settlements dating back to 4000 BCE that reached sizes of up to 320 hectares, and may have housed more than 10,000 people.

These findings shift our understanding of early urbanization and reveal how archaeologists can develop entirely different narratives about the past from the same material evidence.

Discovery of the Megasites

The story of these settlements' discovery begins in the 1960s Soviet Union. A military topographer named Konstantin Shishkin was examining aerial photographs of Ukraine when he noticed peculiar shadows on the ground. These shadows, visible only from the air, were caused by differences in plant growth due to buried archaeological remains. Plant roots could penetrate deeper into the soil where there was once a ditch, resulting in taller growth. Conversely, where roots encountered stones, the stems remained shorter.

These growth patterns were arranged in concentric circles, strongly suggesting human-made structures beneath the soil. Shishkin discovered such features at 250 locations, some covering areas of more than 300 hectares. He hypothesized that these were prehistoric settlements.

To verify these findings, Ukrainian scientists began a large-scale research campaign in 1971 using a method that was just being developed in archaeology: geomagnetics. This technique measures very slight variations in the Earth's magnetic field caused by structures hidden in the ground and the iron particles they contain.

Although labor-intensive, especially with the equipment available in the 1970s, the method allowed researchers to map large areas much more quickly than traditional excavation techniques.

The Cucuteni-Trypillia culture

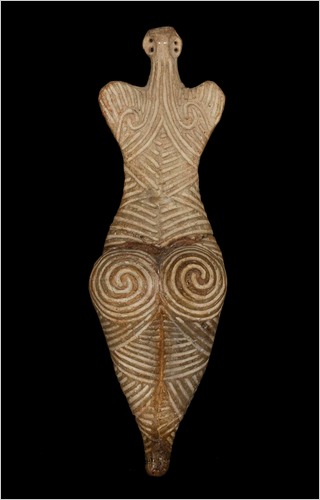

The settlements discovered belong to what archaeologists call the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, named after two early find sites: Cucuteni in Romania and Trypillia in Ukraine, 40 kilometers south of Kyiv. This culture is known for its distinctive pottery - yellowish clay vessels decorated with geometric patterns and curved lines. The culture's influence extended across a vast area, reaching into present-day Moldova.

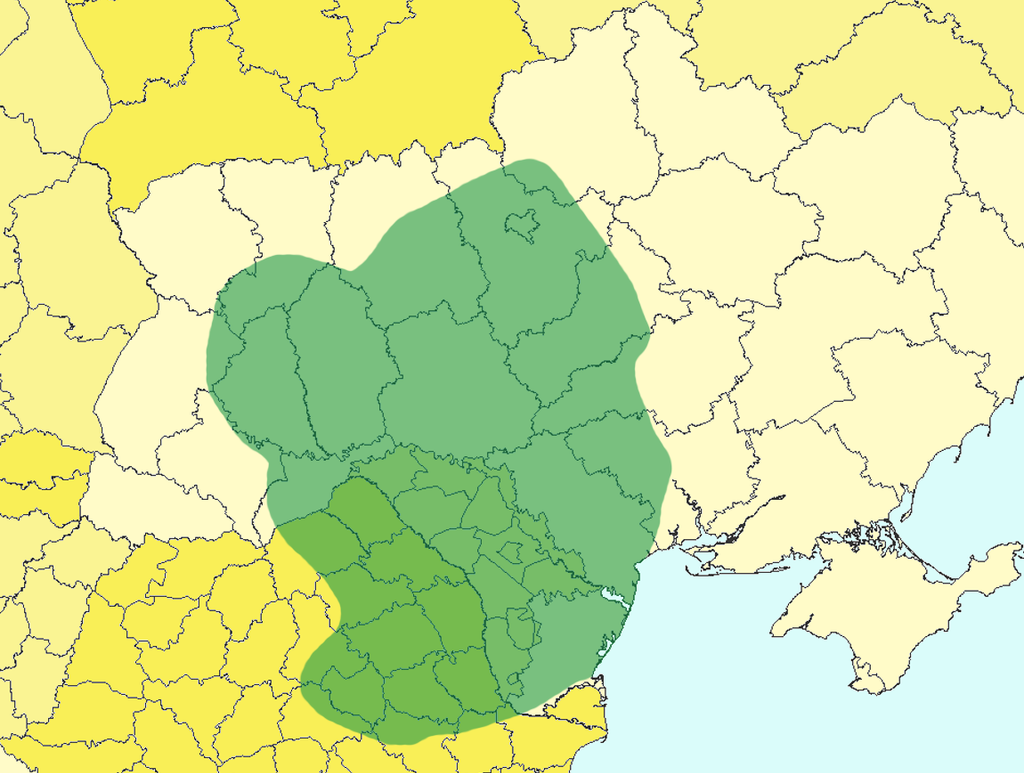

While settlements of various sizes have been found throughout this region, the truly massive sites - what archaeologists term Megasites - are concentrated in Ukraine, along the northern edge of the Pontic Steppe. At least 140 settlements larger than 10 hectares have been identified, with the largest reaching sizes of over 100 hectares.

Structure, layout, and architecture of the Megasites

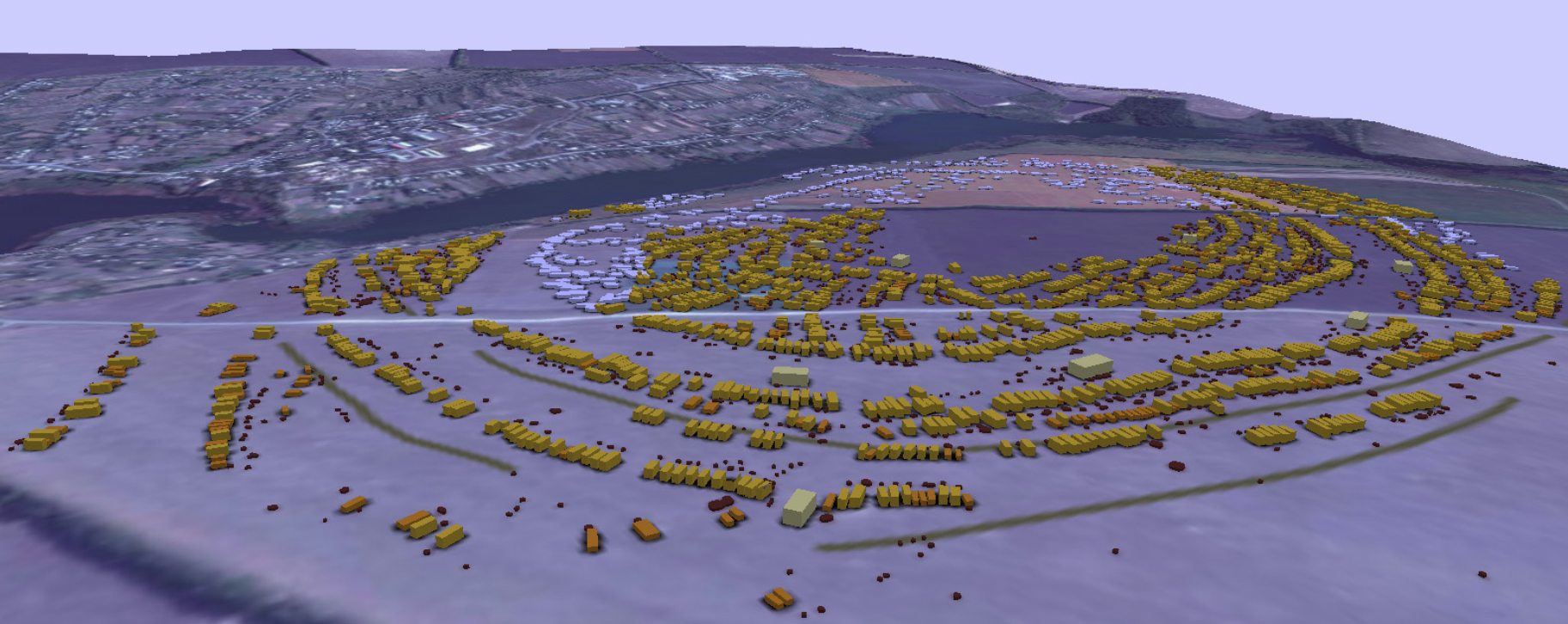

The layout of these settlements is strikingly different from the organic growth patterns seen in many historical cities. Viewed from above, the Megasites are circular or oval, with houses neatly arranged in concentric rings. These rings are regularly interrupted by wide corridors, and the center is typically an open, unbuilt space.

This orderly arrangement clearly indicates planning. The settlements were not allowed to grow haphazardly; instead, plots were marked out and gradually built upon. These are, in effect, the world's first planned cities.The smallest Megasites cover about 30 hectares, while the largest spans 3.2 square kilometers, larger than the principality of Monaco and almost as large as New York's Central Park.

The houses in these settlements were constructed from wood and clay, not unlike modern half-timbered buildings. While there's debate about whether they were one or two stories tall and whether the gables were pointed or arched, the houses were remarkably similar to each other in many respects. They were often of similar size, typically about 5 meters wide and 14 meters long. Johannes Müller, an archaeologist from the University of Kiel who has been researching these sites since 2011, describes the architecture as reminiscent of Lego, suggesting a modular system of construction.

Intriguingly, the houses were eventually burned down, not by attackers during a conflict, but in a regulated manner by their inhabitants. The motivation for this practice remains a matter of speculation.

Society and social structure of Trypilian Megasites

The nature of the society that built and inhabited these Megasites is a subject of intense debate among archaeologists. Their interpretations vary widely, highlighting how the same archaeological evidence can lead to very different conclusions about past societies.

Some archaeologists, including Mykhailo Videiko from the University of Kyiv, favor a more traditional view. They argue that as societies grow larger, social differences inevitably increase. Videiko sees evidence in the large Trypillia settlements for a hierarchical social order with a chieftain at the top.

This interpretation also draws on the theory proposed by Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas between 1974 and 1991, which posited that European society was originally female-centered, matriarchal, and peaceful, worshiping a "Great Goddess." According to this view, patriarchy only became dominant with the immigration of Indo-Europeans in the Bronze Age.

Videiko and like-minded colleagues interpret the numerous terracotta figurines found in the Megasites as representations of female deities. They suggest that the large, prominent buildings (termed Megastructures) found in these settlements were temples dedicated to these goddesses.

In stark contrast, the group led by Johannes Müller in Kiel sees no evidence for such hierarchies or religious structures. Instead, Müller interprets the Megastructures as communal assembly houses where decisions were made collectively. Given the similarity of the residential homes and the lack of evidence for institutionalized social differences throughout the settlement, Müller's team proposes an egalitarian society.

They suggest that people moved to these large settlements from the surrounding areas, effectively depopulating the regions around them. This maximalist model estimates the population by counting the number of houses and multiplying by an estimated 5-10 inhabitants per household, arriving at figures between 5,000 and 15,000 inhabitants.

A third interpretation, proposed by John Chapman from Durham University and his colleague Bisserka Gaydarska, suggests a different scenario altogether. Based on experimental archaeology and analysis of ancient plant pollen, they argue that the settlements were not permanently inhabited by large populations. Instead, they propose that the Megasites were used seasonally as pilgrimage centers, where people from the surrounding area gathered once a year to perform rituals and celebrate festivals.

Environmental impact and sustainability of Trypillia Megasites

Researchers also disagree on the Megasites' environmental impact. Müller's team, based on soil analyses, concludes that the inhabitants practiced sustainable agriculture and animal husbandry. They argue that while significant deforestation was undertaken to meet the settlements' wood needs, leading to the expansion of the steppe, the ecological carrying capacity was never exceeded. In fact, they suggest that the clearing of forests actually improved soil conditions, contributing to the formation of the highly fertile chernozem (black earth) soils.

Chapman and Gaydarska, on the other hand, argue that if all the houses had been in use simultaneously and subsequently burned down, the amount of wood required would have necessitated extensive forests. However, they find no evidence of such large-scale deforestation or intensive grain cultivation (which would have been necessary to feed thousands of people) in the 6,000-year-old plant pollen samples from the soil.

Regina Uhl, a researcher at the German Archaeological Institute specializing in the prehistoric archaeology of the Black Sea region, takes a more cautious stance. She points out that the carbon-14 dating method, which the Kiel archaeologists use to estimate how many houses were inhabited simultaneously, is imprecise for the beginning of the 4th millennium BCE, with potential variations of up to 150-200 years. This makes it impossible to determine with certainty whether all houses were inhabited at the same time, although it also doesn't rule out this possibility.

Were the Trypillia Megasites actually cities?

The designation of these settlements as cities is also a matter of debate. Traditionally, the Mesopotamian city of Uruk was considered the world's first city. In the 4th millennium BCE, Uruk was home to people who did not have to engage in agriculture themselves - true urbanites.

They obtained their food from the surrounding hinterland, had a ruling elite, monumental architecture, and an administrative system that included the development of writing. For a long time, archaeologists considered these features essential characteristics of a city.

The Trypillia settlements, however, exhibit none of these features. Nevertheless, Johannes Müller now considers them cities. He argues that the key feature of a city is not its size, but rather a concept and planning that is evident from the beginning. Moreover, he suggests that a crucial aspect of urban life is that one doesn't know all the people living in the same settlement, even those just 1.5 kilometers away.

The end of the Trypillia Megasites

Around 3600 BCE, the Megasites disappeared. The reason for their abandonment is another mystery, with no evidence of conflicts, violence, or external invasion. The cause seems to have been internal.

Müller sees the end of the Megasite phenomenon as connected to their egalitarian structure. He suggests that over time, decisions were made by increasingly smaller groups, as evidenced by the disappearance of smaller assembly houses. Meanwhile, population numbers were rising, necessitating new forms of communication and administration.

Unlike in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China, where writing developed independently due to administrative needs, the people of the Megasites did not invent writing. They may have used a system of tokens for counting, but this apparently wasn't sufficient for managing their large, complex societies.

The Trypillia Megasites represent an intriguing chapter in human history, challenging our understanding of early urbanization and social complexity. Their significance can be summarized in several key points:

- Rewriting history: They push back the timeline of large-scale, planned settlements by centuries.

- Complexity: They demonstrate sophisticated planning and organization in Neolithic Europe.

- Longevity: The phenomenon persisted for 500 years, longer than many later social orders.

- Mystery: Despite extensive research, many aspects of these settlements remain debated and poorly understood.

- Ongoing research: As Regina Uhl states, "We're not done with it yet," highlighting the continuing importance of these sites in archaeological research.

The Trypillia Megasites offer a glimpse into a complex, organized society that existed in Eastern Europe millennia before the rise of classical civilizations. As research continues, they may well rewrite our understanding of the origins of urban life and social complexity in Europe and beyond, reminding us that the path of human development is far more diverse and complex than we once believed.

Related:

- Ukraine’s European heritage is in its language’s DNA

- Texty: Russian museums refuse to return 110,000 Ukrainian looted treasures

- Sensational archaeological find uncovers “Ukrainian Stonehenge” in eastern Ukraine

- Ukrainian experts hope UNESCO status will help preserve ancient Trypillian culture

- Archaeologists unearth unique amphora-shaped pendants in Poltava Oblast

- Remarkable find near Khortytsia. Underwater archaeologists raise ancient Cossack gun carriage to surface