Six days into Ukraine's incursion into Russia's Kursk Oblast, mixed Ukrainian troops have advanced 30 km across the border, with reports suggesting partial Ukrainian control over the city of Sudzha.

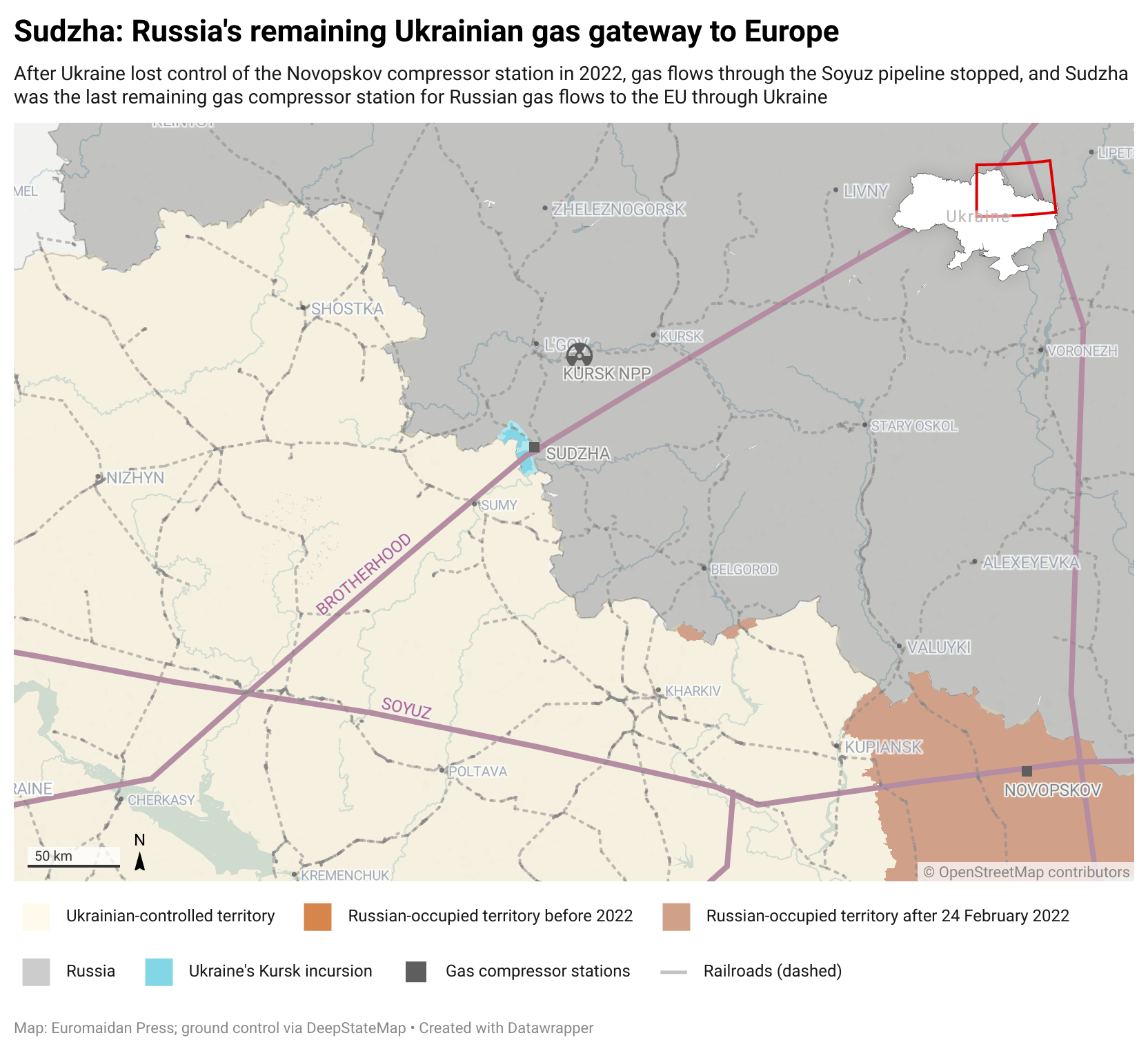

Sudzha serves as the gateway for Russia's remaining gas supplies to the EU, while the strategically significant Kursk Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) is located just 50 km away.

These developments have ignited widespread speculation about Ukraine's potential energy-related objectives in the operation and its implications for EU gas supplies.

We interviewed Mykhailo Gonchar, Ukrainian energy expert and President of the Centre for Global Studies Strategy XXI, to address key questions: Would Russia halt the gas flow through Sudzha? Does Russia still maintain gas leverage over the EU? Could Ukraine realistically aim to seize the nuclear power plant?

Sudzha: one of Russia's two remaining gas lifelines to Europe

Sudzha, a small town in Russia's Kursk Oblast near the Ukrainian border, has gained strategic importance due to its gas compressor station. This facility serves as a critical point for Russian gas transit to Europe through Ukraine.

The Sudzha gas metering station is one of the main entry points for Russian gas into Ukraine's transit system. Before Russia's full-scale invasion in February 2022, there were two primary gas entry points from Russia to Ukraine: Sudzha and Sokhranovka. However, in May 2022, Ukraine's gas operator ceased accepting gas through Sokhranovka, citing loss of control over the facility due to Russian occupation of the area. This development left Sudzha as the sole remaining transit point for Russian gas flowing to Europe via Ukraine.

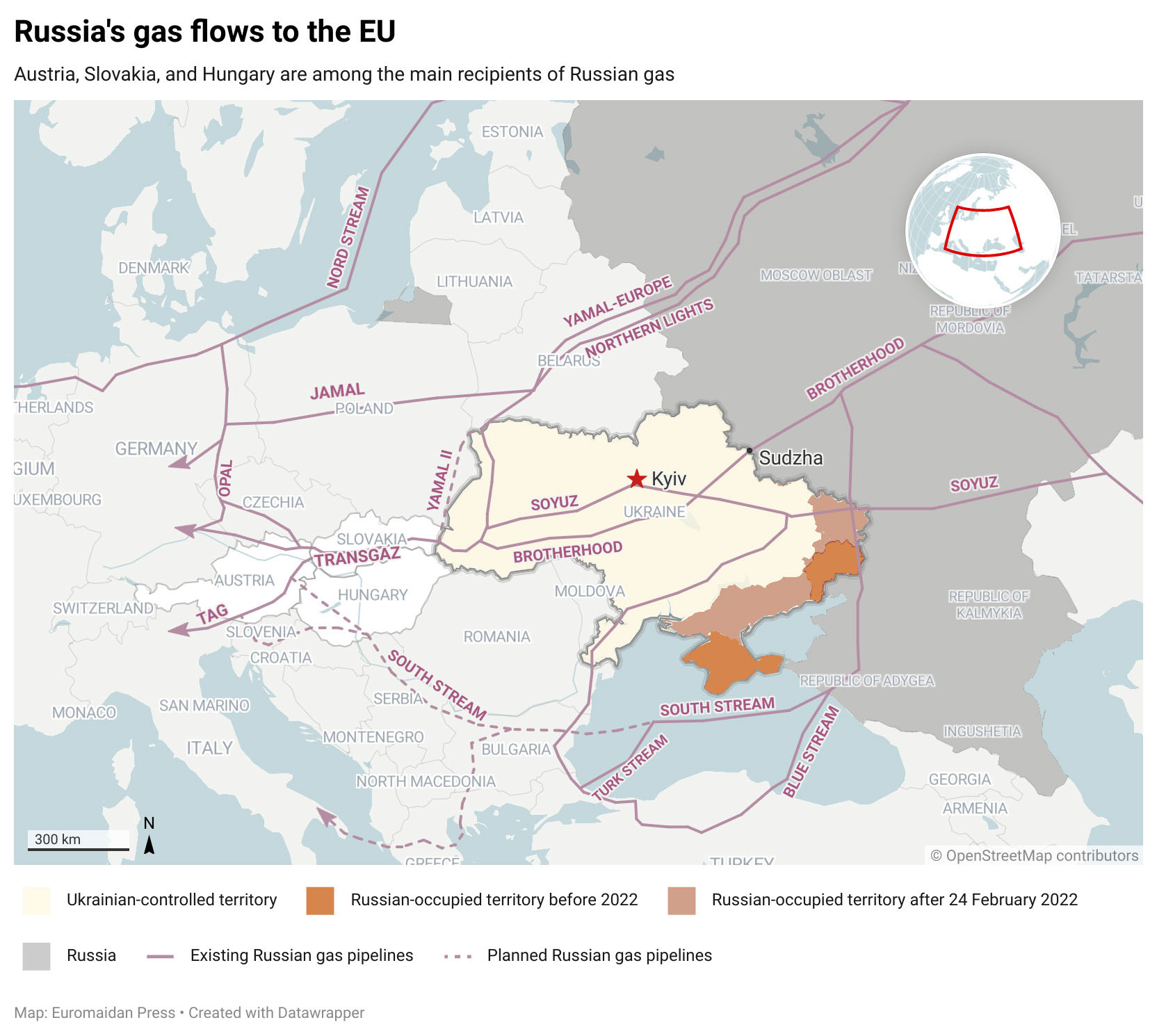

As of 2024, Sudzha handles approximately 43 million m3 of gas per day, accounting for about half of Russia's gas exports to Europe via pipeline. The TurkStream pipeline covers the remainder.

Following the outbreak of fighting, Moldova, one of the countries receiving gas through the Sudzha gateway, placed its gas market on high alert. However, despite concerns, daily gas flows were only slightly reduced, and no significant challenges to gas transit materialized.

No plans to seize the Kursk Nuclear Power Plant

According to Mykhailo Gonchar, Ukraine never had plans to seize the Kursk Nuclear Power Plant, despite widespread online speculation about a potential plan to capture the station and negotiate its exchange for the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, occupied since 2022.

The power plant is located 80 km from the border, with the road distance extending to 120 km. Gonchar argues that if Ukraine had planned to capture and maintain control over such a strategically important object, it would have deployed much larger forces.

Furthermore, he contends that if Ukraine had such plans, it would have delivered the main surprise blow toward the direction of the plant, with other military operations playing a secondary role.

Gonchar suggests that the real reasons for Ukraine's unexpected incursion into Russia could be related to logistics rather than energy. Railroads running through the regional rail center of Lgov deliver supplies south, where the rail-reliant Russian army had made an incursion to the north of Kharkiv in May.

By invading the Kursk Oblast, Ukraine may intend to disrupt the flow of military supplies by destroying rail infrastructure such as bridges. Even if Ukraine is forced to retreat, Russians will need time to rebuild and, furthermore, will be within firing distance from Ukrainian territory, Gonchar believes.

Gazprom unlikely to cut off gas through Sudzha

Russia's state gas company Gazprom could have cut off the gas flow to the EU through the Brotherhood pipeline in retaliation for the tacit support that the West had shown for Ukraine's Kursk incursion. The pretext could have been Russia's loss of control over the Sudzha gas compressor station, similar to how Ukraine stopped pumping gas through the Soyuz pipeline after losing control of the Novopskov gas compression station in 2022.

However, Gonchar believes this is unlikely to happen in the future. At the other end of the pipeline are what he refers to as the Kremlin's "Trojan horses" -- Hungary, Slovakia, and, to a lesser degree, Austria.

"The leadership of these three countries holds maximally Kremlin-loyal positions in the EU. So even though the Kremlin would likely want to switch off the gas flow, it would mean, first of all, punishing their own that are serving the Kremlin's interests. This is why Russia desperately wants to preserve the 'status quo' of gas flows and ignore the EU's statements," Gonchar argues.

Trending Now

Apart from the need to supply its friendly states, Gazprom is in a difficult financial situation and desperately wants to return to the EU market. This is another reason why Russia is unlikely to switch off the flow through Sudzha, which earlier could be considered a minor fuel pathway but currently supplies half of Russia's gas volumes to the EU.

Kremlin's actions helped wean the EU from Russia's gas dependence

In the last two years, the EU has managed to radically diversify its supply after decades of reliance on the Kremlin. However, Gonchar believes this is hardly Brussels' accomplishment; rather, it is Russia's.

Before 2022, Gazprom supplied 46% of the EU's gas. When the bloc resolutely supported Ukraine after Russia's invasion, the Kremlin attempted to weaponize gas to force the EU to stop supporting Ukraine.

To achieve this, Russia attempted to curb the flow of gas to the EU market to drive up gas prices. At the peak of the crisis in 2022, gas prices in the EU topped $3000 per 1000m3, up from their usual $300-500 per 1000m3.

Russia used contrived pretexts to reduce gas supplies to the EU market:

- A conflict with Poland led to Russia stopping gas pumping to Germany through the Yamal-EU pipeline, accusing Poland of arbitrarily taking control over Gazprom's share in their joint venture for the Polish section of the pipeline.

- The largest blow to the EU's market was delivered with the Nord Stream Siemens turbine drama in 2022. Russia claimed that turbines in the Portovaya gas compressor station malfunctioned, leading to reduced gas flows to Germany. This claim is questionable, as the simultaneous failure of eight turbines is highly improbable, suggesting a political rather than technical reason for the halted gas flows.

The Kremlin leveraged the allegedly broken turbines to pressure the West to lift sanctions enacted on Russia for the war against Ukraine. This led to diplomatic tensions, with Germany petitioning Canada to temporarily lift sanctions to allow turbine repairs.

Gonchar explains that the Kremlin's message was essentially, "You, the West, can only blame yourself because you imposed sanctions on us for what you consider an invasion of Ukraine."

This situation continued until early fall 2022 when Gazprom's Western European customers threatened serious fines for breach of contract due to gas supplies falling below the minimum stipulated volumes.

Subsequently, a mysterious explosion damaged both Nord Stream I and II pipelines. Gonchar believes this was an insider job, with Russia aiming to manufacture a force majeure to explain its low gas supplies.

However, all these attempts at weaponizing gas forced the EU to wean itself off Gazprom's gas dependency. The EU Commission did not manage to convince all the EU members to impose gas sanctions against Russia; therefore, the bloc took measures to drastically reduce its fossil fuel consumption, as well as started purchasing American LNG.

"By attempting to weaponize gas supplies, Gazprom lost the EU gas market. Currently, Nord Stream I and II do not operate, and neither does Yamal-Europe. Only the TurkStream branch through the Black Sea remains and the route through Ukraine, which Russia is forced to use despite not wanting to," Mykhailo Gonchar explains.

However, now the Kremlin has understood that losing the EU market is a catastrophe. Russia hoped that China would buy all the gas. But it was in for a rude awakening: China demanded domestic, subsidized gas prices, leading to the stalling of the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline, rendered unprofitable by Beijing's demands.

Gazprom's crisis is why the Kremlin can be expected to make attempts to return to the EU gas market at any price and trick in the near future, Gonchar believes.

Related:

- Germany tries to wrench a turbine out of Canada’s sanctions. It should press on Russia instead

- Kursk incursion: why is Ukraine taking the war to Russian soil?

- Kursk incursion: experts debate Ukraine’s objectives as Kyiv consolidates blitz gains

- Ukraine’s surprise Kursk incursion: lifting spirits or stretching resources?