On 31 July 2024, at 5 pm, in the southern Ukrainian city of Kherson, as the record heat subsided, Oleksandr, a tall hollow-chested man in his 40s, packed trash into two plastic bags, put on a black baseball hat, stepped outside, looked at the clear blue sky, took a few steps towards the overfilled trash container at the end of the lane and heard loud buzzing.

A Russian military drone whirred about ten meters above his head like a giant bumble bee. Black, gangly, it hovered above, and a black-and-white Coca-Cola can was dangling from its bottom. Oleksandr froze. He knew that was an explosives load.

Drones—skids—have been dropping grenades and homemade explosives on the people in his neighborhood by the Dnipro River for two months. Breathless, Oleksandr jumped into the dense bushes and flattened against the fence. His heart beating fast, feeling like a hunted animal, Oleksandr raced towards the remains of a building wrecked by shelling across the lane. In his flip-flops, still clutching on the garbage bags, he ran like he had never run before.

The drone darted down, chasing him, hissing, squealing. Then, suddenly, it changed its course, plummeted into the fence—right where Oleksandr was hiding a moment ago—and with a crackling noise went up in black fumes.

The chase lasted about a minute. It wasn’t the first time, and it would not be the last, thought Oleksandr.

The next day, Russian military drones attacked Kherson region residents about 25 times. Nadiya, 45, a vigorous woman with hearty laughter, was cooking borshch in a private house by the Dnipro River when she heard buzzing. She peeked out the window, looked up, and saw a drone hovering above her roof. After ten minutes, it dropped the explosives into her yard, raising a dust storm.

“It was as if the Earth collapsed on top of me. The burning smell—no, stench!—was like ethyl alcohol. Thank God it was a small explosive,” said Nadiya. “I ended up with a small crater in my yard. I see these drones every day. Five or six might fly past me in the morning, maybe at lunchtime. They become active in the morning or the evening.”

Sveta, a short brunette in her late 40s, lives in a family house close to the river. Not much of her family is left: her husband of 25 years burned alive in a car after an artillery attack; her mother was killed by a Russian shell. To step outside, Sveta, just like her neighbors, has to first listen, then examine the skies, and, if all is clear, walks in short bursts, hiding in the bushes or under the trees.

“As soon as we leave the house,” explained Sveta, “two drones may follow. One drone starts monitoring. It is not loud. It summons the second drone: a killer drone that carries the explosives, chases the person, and then either drops the load or falls and blows up with it. This killer drone is loud. It hisses and squeals. Both drones go after civilians, be it a man, be it a woman, be it a child. Anyone is a target: elderly people, children, adults, bicyclists, someone walking a dog.”

Skids in Kherson: Russian Mavic drones and FPVs

The Kherson military administration confirms that Russian military drones regularly drop explosives on civilians in the city and suburbs of Kherson.

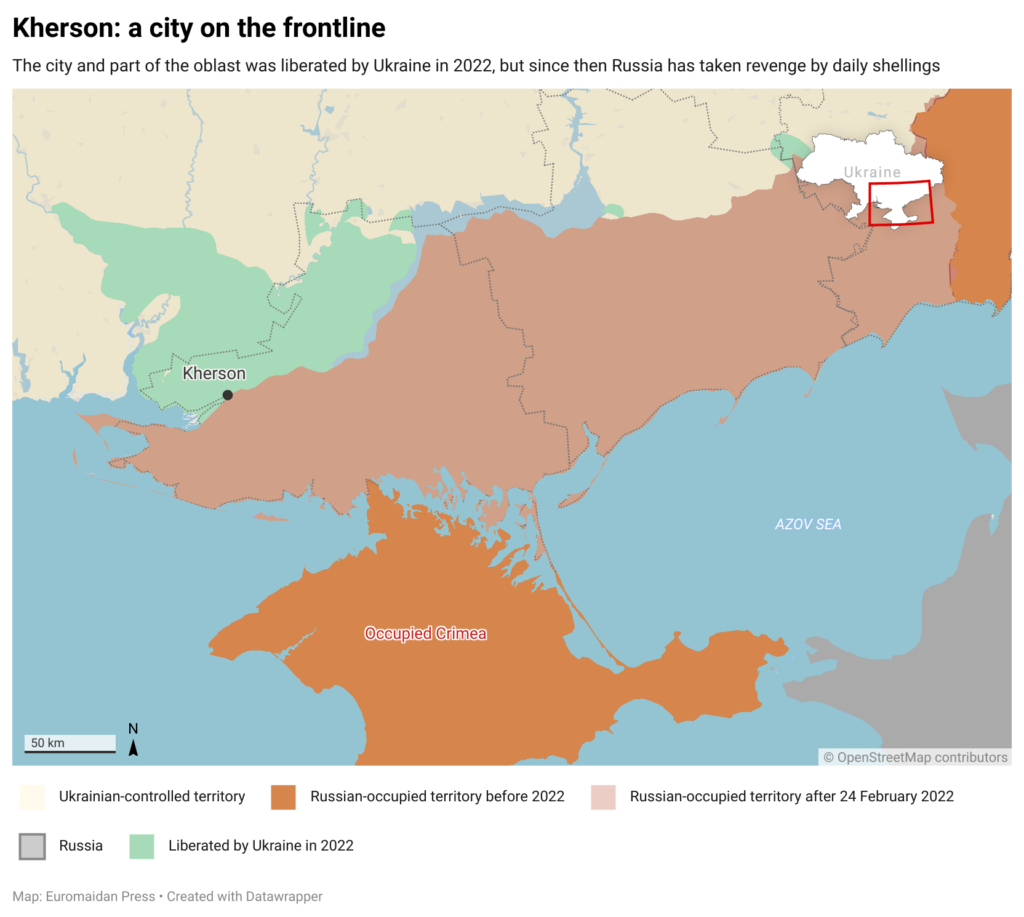

Kherson Oblast, a strategic region in southern Ukraine, has been under a nine-month occupation and experienced relentless attacks since its liberation in November 2022. In June and July 2024, residents witnessed the transformation of drones from surveillance units into weapons systems hunting and killing human targets, primarily civilians.

In two months, drone attacks injured and killed more than 50 civilians, and the attacks are on the rise.

On 6 August, in one day only, drone attacks killed one and injured 12 civilians. In Kherson, one FPV drone flew inside an apartment of a nine-story residential building; another one dropped explosives near a group of old ladies sitting on a bench in the yard. Yet another drone attacked a local store, damaging the premises and wounding one man.

In another district, a drone attacked a municipal service building, a third strike like this in the last week.

Russian drones also targeted trucks in the coastal areas of the city. In Beryslav, the Kherson Oblast, a Russian drone dropped explosives on a 45-year-old man who died on the spot. A 34-year-old woman sustained an explosive injury and concussion while in her own home in Bilozerka.

In Stanislav village, about 5 Russian drones attacked an abandoned gas station and targeted women on the street. A 68-year-old local woman received an explosive injury, a contusion, and a shrapnel wound to the abdomen and was hospitalized. A 56-year-old woman received an explosive injury, a contusion, and a shoulder injury.

Locals call these drops “human safari.” The world is generally unaware of this dystopian development.

To attack civilians in Kherson, the Russian military uses Mavic and First Person View (FPV) drones, unmanned aerial vehicles guided to their target by remote pilots. Both models are modified versions of commercially available models, equipped with cameras that send live videos to the operators. Both Mavics and FPVs may carry explosives, often packed with shrapnel.

A Mavic drone equipped with a high-resolution camera performs reconnaissance. It usually does not crash on impact and can return to its operator. Occasionally but rarely, Mavics can be modified to drop small explosives.

Hi, I'm Zarina, a frontline reporter for Euromaidan Press and the author of this piece. We aim to shed light on some of the world's most important yet underreported stories. Help us make more articles like this by becoming a Euromaidan Press patron.

The FPV drone carries a warhead and attacks targets. Relatively inexpensive, it is designed for single use and detonates upon reaching its target. According to a local Telegram channel, Kherson: War without Fakes, FPV drones carry different types of projectiles and improvised explosive devices (IED). Shrapnel often flies in multiple directions, incurring injuries and damage.

Oleksandr Tolokonnikov, the head of the Kherson military administration, explained the challenges faced by the Ukrainian electronic warfare (EW) units, as the Russians change frequencies, complicating efforts to counter the drone attacks. "Our army has EW systems, but they are not sufficient to cover the coastal front. So the drones continue to enter our space from above and then descend to target civilians," he said.

While the Ukrainian military is hastily working on reprogramming their EW systems, the deadly tandem of Mavics and FPVs are moving past the coastal areas to attack the residents of downtown Kherson.

What kind of a human can hunt other humans?

In mid-July, Victoria Orlova, a slender woman with big brown eyes and long dark hair, in her late 30s, parked her car in the very heart of Kherson by a grocery store. As she got out of the car, she heard a loud banging sound, instantly followed by another. Before she could move, a long object fell right by her feet with a deafening blast.

It was an explosive load.

Victoria, who lived in Kherson throughout almost two years of shelling and had been under artillery fire several times, knew to fall on the asphalt and crawl towards a poplar tree. Explosions went on. Everything was covered in thick smoke.

When the attack stopped, Victoria made it back to the car, her hands shaking, gasping for air. Fighting a severe panic attack, she drove to a hospital where the doctor diagnosed a contusion. It was her lucky day, though. If the drone had not malfunctioned, she might not have seen her teenage daughter and husband ever again.

Yet, every day, Victoria and her family face risk: since Kherson is located one kilometer from the Russian military, it is easy for the drones to “hunt people like at a shooting range,” said Victoria.

“Was it God’s will? What saved me?” asked Victoria. “And what kind of human can hunt other humans?”

Mykyta, 18, a smiling tall, and robust young man, studies music, loves singing, and just got accepted to a college. He loves his white Labrador Ceaser who hides under the bed, hearing the drones and explosions. On 31 July, Mykyta woke up around seven o'clock and, next to his mother Svitlana, he stood under the awning in the yard and watched drones fly by. They had never seen an attack like this before.

Like daddy longlegs, with lethal jars filled with explosives hanging from the bottoms, the drones flew rather slowly from the Russian-occupied, “left” bank past their house, heading up, towards downtown. Svitlana and Mykyta could see the hellish procession well as the drones flew rather low, about ten meters away.

Svitlana, a cheerful doctor and volunteer in her 40s, drank coffee and counted: “Here it flies. Here, in 30-40 seconds, a cracking sound of explosion follows. Here, the drone hurries back empty, rushing towards the left bank.” From 7 am to 11 am, she counted 13 drones. Their noise reminded her of a motorcycle driving far away or a broken fan.

“We have no military here,” said Svitlana. “They shoot at children and the elderly. Yesterday, one drone dumped explosives at an old lady in her 90s. Her yard was damaged and she received a concussion.”

Further down the river, close to the Antonivskyy Bridge, destroyed during the liberation of Kherson, by a rather miraculously still working oncological hospital, drone attacks are even more fierce.

On 26 July, a drone hit a bomb shelter in front of a vegetable stand, next to a summer café, injuring four civilians. A man in his 60s, with a bandage on his cheek, said, “I was right here, at 1 pm, sitting on a bench, when a drone flew here, blew up and fragments cut my face and shoulder.”

Tetiana and Sasha, good friends and neighbors, also in their late 60s, standing in line at the vegetable stand, shared their stories. Tetiana said, “I was sitting on a bench with a group of my lady friends when a drone flew into the yard. I started to run towards my building, raised my eyes, and saw it hovering over the sixth floor, over Sasha’s car.”

“My car was broken as the explosives fell on it,” confirmed Sasha, showing the photo of his broken vehicle. A store nearby gets hit quite often, too, they said. On July 3, at least four civilian cars got damaged by skids in front of the hospital.

Kherson, paralyzed but alive

The Russian military drone attacks have a severe impact on the civilian population as they paralyze already hard life in the battered city.

Victor Shushlyanikov, an Internet provider engineer in his 50-s, with a neatly trimmed silver mustache, tanned face, and tired blue eyes, fixes lines damaged by shelling and spends most of his work day outdoors. Several times a day, he hides underneath the walls or runs to the nearest bomb shelters hiding from the drones as they fly close and circle for a long time, looking for a target. Back home, Victor finds no rest: his private house is close to the Dnipro River. In the morning, leaving for work or trying to clean the yard turns into a hide-and-seek game, played against dozens of drones.

“Kherson used to suffer mainly from missiles, artillery, mortar, and tank attacks. Since July, the number of drone attacks has greatly increased. They are looking for military objects and if none is around, they drop explosives on random targets, including civilians, civilian cars, or houses.

There must be no point for them to carry the load back across the river,” said Victor. “Drone attacks are scarier than shelling. During artillery shelling, you have the opportunity to run for cover and they are not aiming at you. Drones are hovering over you and at any moment you expect a grenade to fall directly on your head.”

After a Russian artillery or drone attack, the Russians use FPV drones to target the first responders: police, communal services, rescuers, firefighters

Survival in coastal areas is becoming more and more difficult. The postal service, Nova Poshta, temporarily stopped delivering mail to several coastal areas. Volunteers who used to deliver humanitarian aid avoid driving along the “streets of death.”

The police minimize time spent at the sites of attacks due to the Russian tactic called “double tap.”

After an artillery or a drone attack, the FPV drones wait for the municipal services to arrive to save casualties from under the rubble or to put out fires. Then, the drones attack the first responders, aiming at the personnel. Russian drones routinely target the first responders, city services staff, and vehicles. They track and attack the police, communal services, rescue vehicles, and firefighters’ engines.

Why drones?

The goal of these attacks might be the demoralization of the population. By inciting fear, the Russian military is attempting to force the remaining Khersonians out of the city. 360,000 pre-war population has declined to below 60,000 and numbers are dropping. With no civilians left, Kherson can be reduced to ashes like many cities and towns in Donbas, such as Bakhmut, Avdiivka, Chasiv Yar, and more.

Another likely goal is to terrorize the population by putting pressure on the Ukrainian government to negotiate with Moscow on Putin’s terms. The Kremlin often uses psyops (psychological operations) to reach its aspirations. In this case, it is undermining Ukrainian resolve and unity in the Kherson Oblast.

The main urban center, Kherson city, located on the “right” Ukrainian-controlled bank of the Dnipro River is heavily damaged by shelling, with the broken pavements strewn with shrapnel, twisted piles of steel and concrete resembling WWII landscapes, and most windows cardboarded, giving Kherson a nickname “the city of wooden windows.”

The oppressive silence is broken by the bursts of machine-gun fire hunting for drones and wild dogs howling. Suburbs and villages of the liberated Kherson region had faced two years of persistent attacks and significant infrastructure destruction. The fields are heavily mined. Efforts to rebuild amidst the attacks lead to new victims.

The invasion has left the local population without jobs, with more housing ruined by the Nova Kakhovka flood. Hospitals and humanitarian aid centers are damaged and destroyed, leading to shortages of medical supplies and hygiene products. Nightly artillery attacks, lack of sleep, and daily terror lead to a mental health crisis.

Many residents of the Ukrainian-controlled territories of the Kherson Oblast have families on the Russian-occupied left bank, in the temporarily occupied territories (TOTs). Ukrainians who continue to resist the invaders do not just face arrests, murders, and tortures, but are also used as hostages and leverage to put pressure on the loved ones of the “right” bank population.

Despite hardships, Kherson’s resilient spirit prevails, with communities organizing art classes, gyms, history lectures, and theater shows in bomb shelters. Drone attacks are aimed to put an end to all resistance.

The deliberate targeting of civilians by drones constitutes a war crime, as drone operators can clearly identify their targets. Despite the clarity of these violation of Geneva Convention, these Russian war crimes are not reported in the national and global press. This lack of coverage keeps these atrocities in the dark and allows them to continue without accountability. The media must report these incidents more thoroughly to raise awareness and push for justice against the perpetrators.

Related: