On 1 August, the United States, Russia, and the European allies exchanged 24 prisoners, marking the largest such swap since the Cold War.

In the high-profile exchange, the West secured the release of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, former US Marine Paul Whelan, and imprisoned Russian dissidents, including Vladimir Kara-Murza.

The list was to include the most high-profile Russian political prisoner, opposition leader Aleksey Navalny. However, he did not live to his planned liberation.

This is the first time Putin agreed to include people with exclusively Russian citizenship in an exchange with Western countries - a practice rooted in Cold War-era diplomacy when the Soviet Union occasionally engaged in high-profile prisoner swaps that included not just foreign nationals but also Soviet citizens, often dissidents or refuseniks.

In exchange, Russia received killers, spies, and fraudsters. One of Putin’s main bargaining chips was Vadim Krasikov, a Russian security service hitman freed by Germany, and Roman Seleznev, who was serving time in the US for a major hacking scheme, among others accused of espionage or cyber crimes.

Navalny swap without Navalny

While this prisoner swap freed some high-profile individuals from both sides, like Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and Russian-American journalist Alsu Kurmasheva, it initially hoped to include Russian opposition leader Aleksei Navalny, sentenced to 19 years under charges of “extremism.” He did not live to see this day, having died in a Russian prison in February under suspicious circumstances.

Leonid Volkov, Navalny's closest ally, expressed mixed emotions about the exchange.

"'The Navalny swap has taken place…but without Navalny. It hurts a lot,” Volkov wrote on X.

Russia’s key figure for exchange - an assassin

The key figure who would secure Navalny’s return would have been Vadim Krasikov, a Russian convicted in Germany for the 2019 murder, allegedly ordered by Moscow, of a former Chechen separatist in Berlin. The Wall Street Journal, which was privy to the brewing exchange, reported that Putin personally wanted Krasikov back for loyalty to the state.

The Russian president even publicly expressed interest in Krasikov's release during a February interview with American commentator Tucker Carlson.

The negotiations dragged on because Germany was hesitant to release a murderer, fearing it would signal to Russia that they could use detainees as bargaining chips to recover those who the Kremlin sends abroad to spy and perform sabotage for Russian goals.

Only through direct appeals, including that of Evan Gershkovich’s mother, to Germany’s Counsellor Olaf Scholz, did the country agree to let Krasikov go for the sake of political prisoners and a handful of German nationals jailed in Russia.

Russia returns criminals, the West returns political prisoners

While Russia returned the murderer and other serious criminals, the US welcomed back Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, former US Marine Paul Whelan, and Russian-American journalist Alsu Kurmasheva - along with several prominent Russian opposition figures, accused of espionage and condemnation of Russia’s war in Ukraine. They all denied these charges.

Several associates of Navalny were among those freed, including Lilia Chanysheva, Ksenia Fadeyeva, and Vadim Ostanin. Russian opposition politician Ilya Yashin, a vocal Kremlin critic, was also part of the swap. He was arrested after he had spoken up about Russian war crimes in Bucha, Ukraine.

Another of Putin’s opponents, Vladimir Kara-Murza, was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2023 for spreading “fake” information about the Russian army after it invaded Ukraine full-scale in 2022, the Kremlin’s codename for criticizing the war.

A 71-year-old Russian human rights activist, Oleg Orlov, and other dissidents were exchanged, as were artist Sasha Skochilenko, who was sentenced to seven years for replacing supermarket pricing labels with anti-war messages, and Kevin Lik, a German-Russian citizen convicted of treason as a teenager.

The swap also included Andrei Pivovarov, who headed the Open Russia foundation, and Dieter Voronin, a Russian-German citizen sentenced on "treason" charges. Patrick Schoebel, a German national detained in St Petersburg for possession of cannabis gummy bears, and Herman Moyzhes, a Russian-German immigration lawyer facing treason charges, were also among those released.

In exchange, Russia received several individuals convicted of serious crimes in Western countries. Apart from Vadim Krasikov, this included Roman Seleznev, son of a Russian MP and Putin ally, who was serving part of a 27-year sentence in the US for a massive hacking scheme that caused $169 million in damages. Another cyber criminal, Vladislav Klyushin, who had been jailed for nine years in the US for insider trading, was also part of the swap.

Trending Now

The exchange included Vadim Konoshchenok, charged by the US with conspiracy related to procurement and money laundering on behalf of the Russian government. Mikhail Valeryevich Mikushin, accused of gathering intelligence in Norway while posing as a Brazilian academic, was another of those returned to Russia.

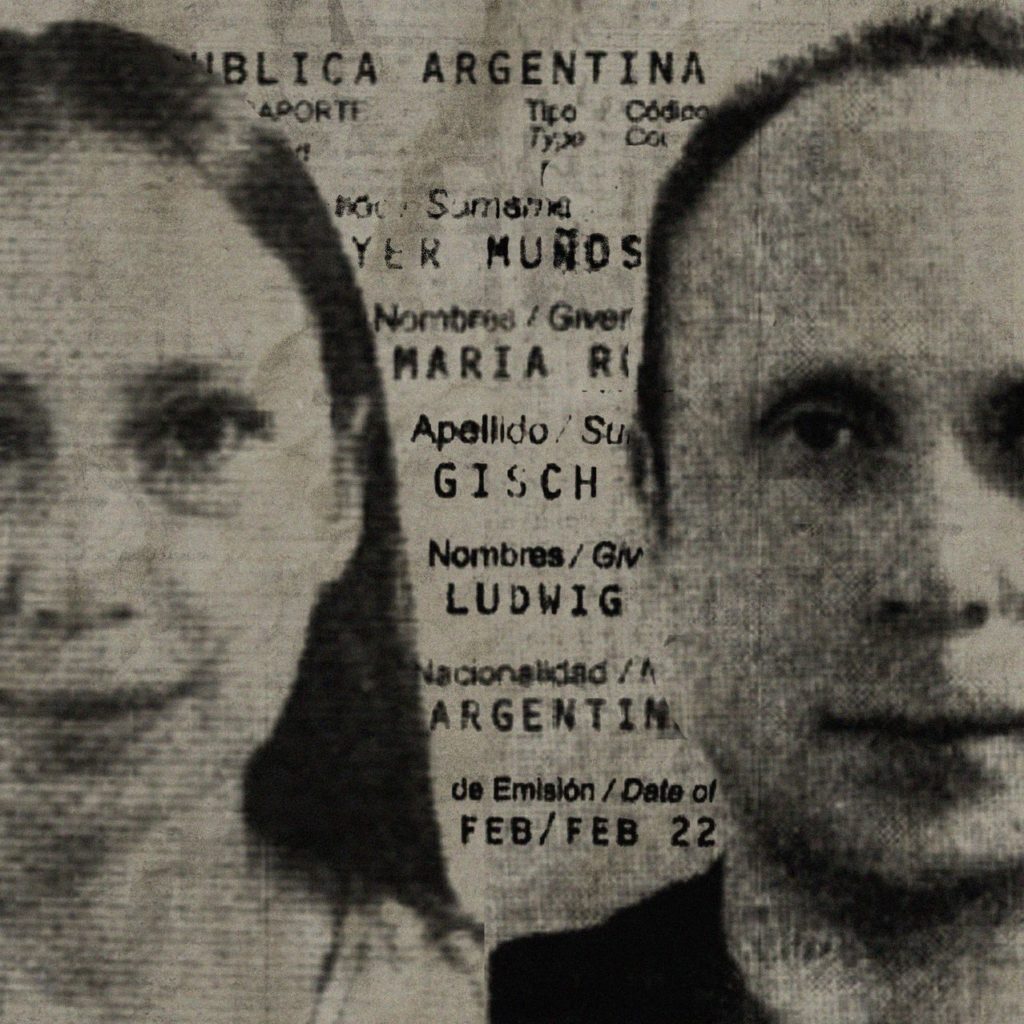

A married couple, Artem Viktorovich Dultsev and Anna Valerevna Dultseva, convicted of espionage in Slovenia, were also part of the deal. They were a couple with children, living under false Argentinian identities, running an IT business and an art gallery in disguise while secretly sending information to their real motherland.

The swap also involved Pablo González (Pavel Rubtsov), a Spanish-Russian journalist arrested in Poland in 2022 on accusations of espionage and links to Russian military intelligence. His case has drawn the attention of organizations like Amnesty International and Reporters Without Borders.

This prisoner swap beneficial for Biden’s image

President Biden emphasized the priority of freeing wrongfully detained Americans abroad in his final months before he leaves office, reiterating this commitment not to seek re-election.

William Courtney, a former US ambassador with extensive experience in US-Soviet relations, told RFE/RL that the prisoner exchange could benefit the Biden administration's image.

He stated that the administration "knows how to deal with great powers who are adversaries [and] knows how to do complex negotiations,” according to RFE/RL.

Courtney also suggested that Russia gains little from holding high-profile prisoners, noting that it "gets nothing but bad publicity internationally" for doing so.

Despite the successful exchange, US officials emphasized that it does not signal a thaw in relations between Washington and Moscow. According to the New York Times, the deal was driven by “cold calculations of national interest” rather than a new détente.

US President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris personally welcomed the freed Americans at Joint Base Andrews in Maryland. Biden hailed the exchange as a "feat of diplomacy" and declared, "Their brutal ordeal is over.”

Worries about a Russia-West rapprochement in Ukraine

In the aftermath of the recent prisoner exchange between Russia and Western countries, a complex web of concerns regarding how this event might be interpreted globally is emerging in Ukraine, as Iryna Kutielieva for European Pravda reported.

One primary concern is that this exchange could be seen as a sign of Russia's willingness to negotiate more broadly. Some worry that certain international voices might use this as leverage to push for peace talks with Moscow despite the ongoing war in Ukraine. As Kutielieva notes, there's a fear that some might overlook Russia's tactic of "taking hostages" to strengthen its negotiating position.

The White House has attempted to preempt such interpretations. Jake Sullivan, the US National Security Advisor, emphasized that negotiations about prisoner exchanges and potential talks concerning the war in Ukraine are entirely separate matters.

However, there's skepticism in Ukraine about whether this distinction will be universally accepted. Kutielieva points out that not all advocates for appeasing Russia may heed these words, potentially increasing pressure on Ukraine to enter negotiations.

None of the exchanged individuals today were Ukrainian citizens. However, scores of Ukrainians are also languishing in Russian prisons. In February, Ukraine’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Dmytro Lubinets, stated that approximately 28,000 Ukrainians — military personnel, civilians, journalists, and children — remain in Russian captivity; however, the number is hard to verify.

Related:

- Biden, Harris welcome freed Americans at Andrews Air Force Base in Washington

- Russian think tank’s “relocant” pitch clashes with unmasked spy couple in Slovenia

- The Times: Ukraine says Russia operates black market of prisoners of war

- ISW: Russia may force Ukrainian prisoners of war to fight in Ukraine