Western-made components essential for weapons manufacturing continue to reach Russia despite sanctions. These critical parts - including microchips, semiconductors, transistors, electrical wires, and metal alloys - are found in missile-destroyed Ukrainian hospitals, homes, and on the frontlines.

A joint investigation by Ukrainian media project Trap Aggressor, German outlets Süddeutsche Zeitung, NDR, WDR, and French newspaper Le Monde has exposed a supply chain funneling EU components to Russia through a network of companies linked to the Russian corporation Promtech and a small Turkish company Enütek.

The investigation identified several Western manufacturers whose products have made their way to Russia, including:

- Infineon (Germany): Largest semiconductor manufacturer

- Tampoprint (Germany): Specializes in pad printing and laser processing

- Attax (France): Produces spare parts, including aircraft seat fastening systems

- Lebronze Alloys (UK/Germany): Manufactures semi-finished and finished products using high-performance copper and nickel alloys

- Molex (US/Germany): Produces electronic, electrical, and fiber optic connectivity systems.

Notably, Ukrainian intelligence reports Molex microchips in Russian Kh-101 cruise missiles, one of which recently devastated Ukraine's main children's hospital Okhmatdyt.

Euromaidan Press will now detail how these components circumvent Western sanctions to reach Russia.

Russia's Promtech funnels Western tech into military production

Promtech, a vast Russian scientific-industrial corporation, operates across 30 regions with 14 manufacturing enterprises and a design bureau.

It produces critical components for aviation, aerospace, ground, and naval equipment, serving major Russian military-industrial clients like Russian Helicopters, Roscosmos, United Aircraft Corporation, and Rosatom.

Founded by Valery Shadrin, a ballistics engineer from the Russian Military Space Academy, Promtech manufactures crucial components in-house but continues sourcing irreplaceable Western parts through third countries, despite US sanctions.

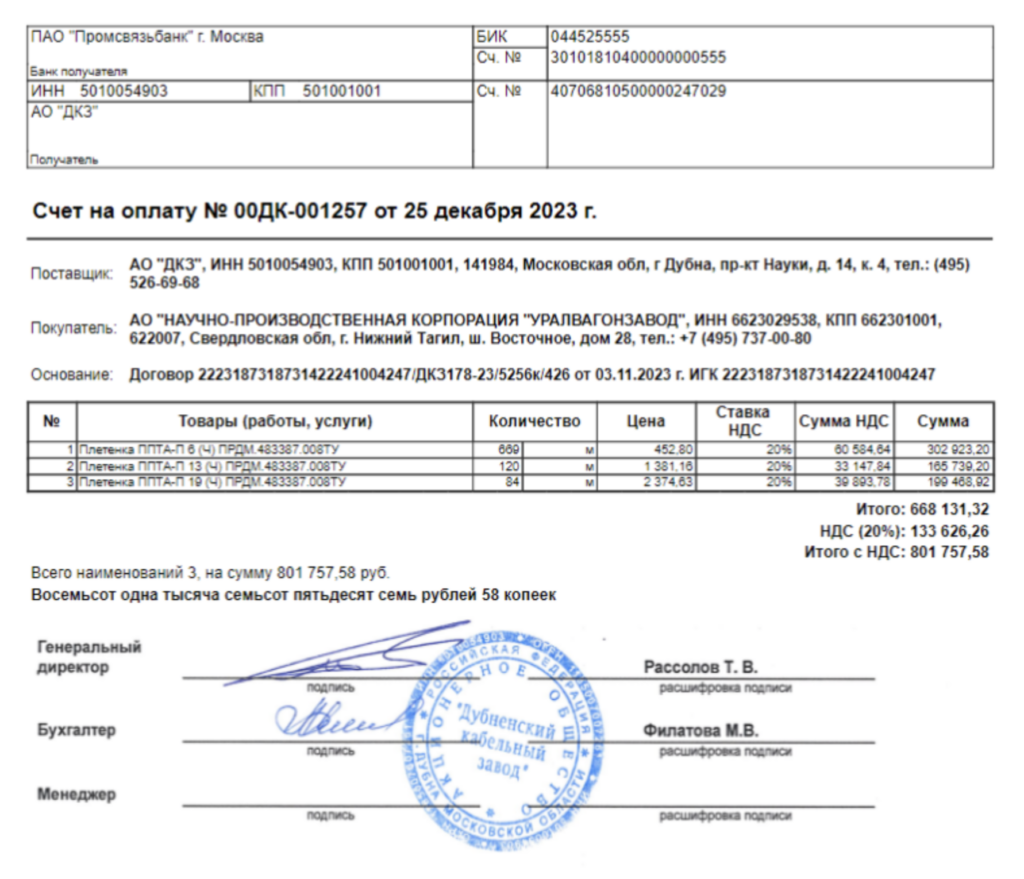

A key Promtech subsidiary, Dubnenskiy Kabelny Zavod (DKZ) in Moscow Oblast, supplies the Russian company Uralvagonzavod, the largest main battle tank manufacturer in the world. In December 2023, DKZ billed Uralvagonzavod for nearly a kilometer of wires, likely one of many such transactions.

However, Promtech maintained access to Western technologies until late 2023 due to an EU sanctions loophole. In 2023 alone, DKZ imported $3.2 million worth of Western-made CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines - crucial for producing missile, aircraft, and drone components that Russia cannot manufacture independently.

Only the EU's 12th sanctions package finally restricted the re-export of these vital machine tools and CNC systems from third countries.

A Turkish furniture company which aids Russia's military

Enütek, an inconspicuous Turkish company in Istanbul, has emerged as a critical conduit for supplying Russia with specialized technology, exploiting Türkiye's exemption from the European sanctions regime.

Despite its mundane self-description as a trader of “machinery, equipment, and office furniture,” Enütek plays a significant role in Russia's military-industrial complex:

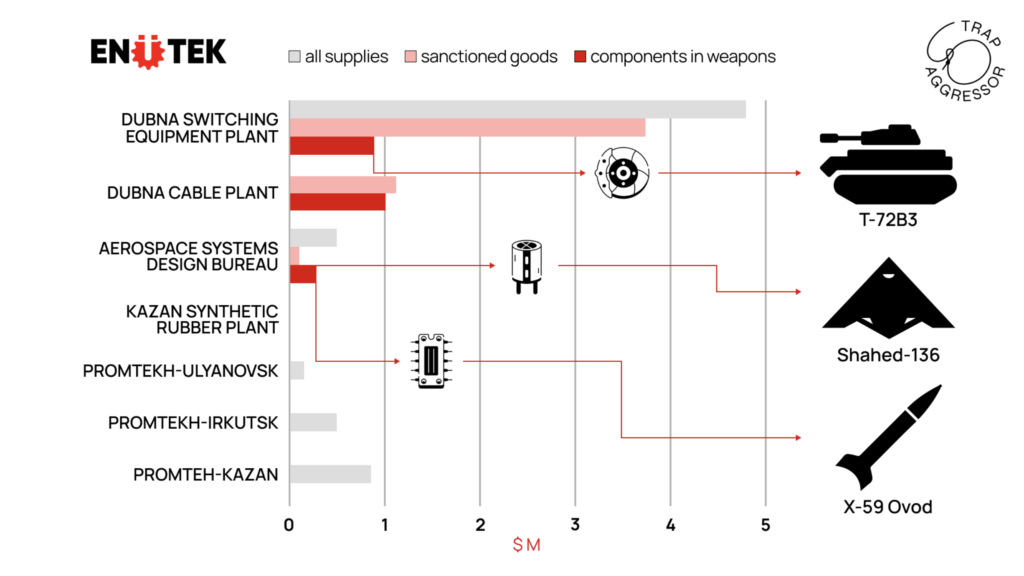

- In 2023, Enütek exported near $8 million worth of goods to Russia.

- Journalists cross-referenced these goods with the Ukrainian Military Intelligence's database. They discovered that at least $850,000 of these exports were Western components for weapons

- The company facilitated the supply of wires to Russian tank manufacturers and procurement of crucial CNC machines for Russia's defense industry.

Enütek's client list includes key Promtech enterprises such as Dubnenskiy Zavod Kommutatsionnoy Tekhniki and OKB Aerokosmicheskiye Sistemy. Through this Turkish intermediary, these companies have gained access to a wide array of critical technologies:

- Electronic switches from the USA

- Precision measurement tools from the Netherlands

- Specialized screws from France

- Heat-resistant temperature measuring devices from Italy

- Various high-tech components from Germany.

The investigation also uncovered the involvement of well-known Western manufacturers. Electrical connectors from Molex, round bars from Lebronze Alloys

for electrical contacts, and semiconductors from Infineon have all found their way to Russian military manufacturers through Enütek's channel.

Bonjour from Moscow: Promtech's French alter ego ITGF

Industrial Technologies Group France (ITGF), effectively Promtech's French arm, established Turkish company Enütek in 2022 amid Russia's invasion of Ukraine. This move marked a significant shift in ITGF's operations.

Prior to the invasion, ITGF was a major supplier of Western products to Russia, with Russian Promtech enterprises being its primary customers. Until May 2022, Promtech owned 100% of ITGF's shares.

Before the invasion, ITGF primarily supplied Western products to Russian Promtech enterprises. Promtech owned ITGF outright until May 2022, with Alexey Shadrin, son of Promtech head Valery Shadrin, serving as ITGF's initial CEO. Valery Shadrin heavily influenced ITGF's major decisions, evidenced by both Shadrins' signatures on 2018 and 2019 meeting minutes.

On 15 May 2022, ITGF's ownership was transferred to Hong Kong-based Interasia Trading Group Limited, making Chinese citizen Zhou Xingze the beneficial owner. Valery Shadrin's signature and Promtech's seal appeared on the transfer document.

Throughout 2023, Enütek supplied Promtech with Western equipment crucial for weapons production. When questioned, ITGF's legal consultant Amandine Hérician claimed Zhou Xingze created Enütek to enter the Turkish telecommunications market, denying knowledge of sanctions-violating exports.

However, several factors suggest collaboration between ITGF, Promtech, and Enütek to circumvent sanctions:

- ITGF's foundation involved Russian Promtech.

- ITGF traded with Russian Promtech group companies for years.

- The creation of Enütek coincided with Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

- Enütek supplied critical products to the Russian defense industry.

- ITGF's name and logo closely resemble those of Russian companies.

Neither Promtech nor Enütek responded to media inquiries, leaving questions unanswered about this apparent sanctions-evasion network.

Sanctions evasion or oversight? Companies respond

When contacted, the implicated companies offered various explanations and defenses:

- Most German firms claimed compliance with international sanctions, asserting they ceased Russian trade since the war's onset in 2022.

- Lebronze Alloys Germany admitted to business ties with Promtech (December 2019) and Enütek (June 2023), but downplayed their significance, citing minimal turnover impact (0.04% and 0.14% respectively).

- Tampoprint acknowledged selling goods to ITGF in 2019, predating the current sanctions.

- Molex, the US parent company, stated they produce "standard products offered by intermediaries worldwide," emphasizing compliance with international law. However, they did not address allegations about their microchips in Russian cruise missiles.

- Infineon claimed to have halted all direct and indirect deliveries post-invasion, implementing "comprehensive measures."

Several companies, including Infineon and Tampoprint, stressed instructing distribution partners to prevent sanction-violating deliveries. Infineon highlighted the challenges in controlling product resale throughout its lifecycle.

Some firms argued they supplied independent intermediaries rather than foreign subsidiaries, implying limited control over final destinations.

Despite these justifications emphasizing compliance or minimal involvement, the volume and nature of exports uncovered suggest a more complex reality. The discrepancy between corporate statements and the flow of dual-use goods to Russia raises questions about sanction enforcement and corporate due diligence.

Benjamin Hilgenstock, an economist at the German Council on Foreign Relations, argues firms could demand appropriate efforts from distribution partners as a basis for continuing business relationships.

"It is an excuse for Western companies to claim that they have no control over what the many intermediaries do," he told Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

Julia Grauvogel, a sanctions expert at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), finds the companies' statements only partially plausible.

"There are clearly individual companies that simply don't want to know where their dual-use products end up," she told Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

However, she acknowledges smaller companies may struggle to adapt to and correctly classify their deliveries under current regulations.

****

Despite Kremlin assertions, Russia's economy remains heavily reliant on Western technologies for both civilian and military production. The European Union's efforts to curtail this dependency through sanctions and legal action reveal a complex challenge.

Western manufacturers play a crucial role in this landscape. They must conduct rigorous due diligence on clients, especially those outside the EU, to prevent sanctions evasion. The accountability of European companies in this process is paramount.

The latest EU sanctions package attempts to address this by mandating "best efforts" in client verification. However, the efficacy of these measures ultimately depends on stringent oversight by regulatory authorities.

Read more:

- Kh-101: the Western parts fueling Russian missile that hit Kyiv hospital

- EU issues guidance to prevent evasion of sanctions imposed on Russia

- Trap Aggressor: Key Russian defense complex businessman not sanctioned, lives lavishly in Europe

- Watchdog: US comms company Iridium keeps Moscow office, works for Russian defense industry