The Swiss military correspondents wanted action; the 93d brigade wanted to oblige. Vladyslav Ovcharenko, callsign “Tourist,” had an idea: attach a munition to a racing drone bought online.

Donning goggles, he sped the drone kilometers away to a Russian-controlled village. Picking up speed, it slammed inside the blue doors of a hut with soldiers inside. Plumes of smoke followed; back at base, the Ukrainians cheered: they had turned a munition into a flying remote attack weapon.

And just like that, in July 2022, the FPV military drone revolution was conceived. This technology now defines the battlefield in Ukraine, making old doctrines obsolete. It led to the failure of Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive: western demining machines now last only hours due to swarms of Russian drones. While Ukraine initially led in FPV technology, Russia is scaling up drone production. The outcome of the war depends on who innovates faster.

Euromaidan Press has talked with Ukrainian FPV drone producers to understand why these cheap flying bombs have become key, and what could come next.

The outcome of the war depends on who innovates faster.

What FPV drones can do

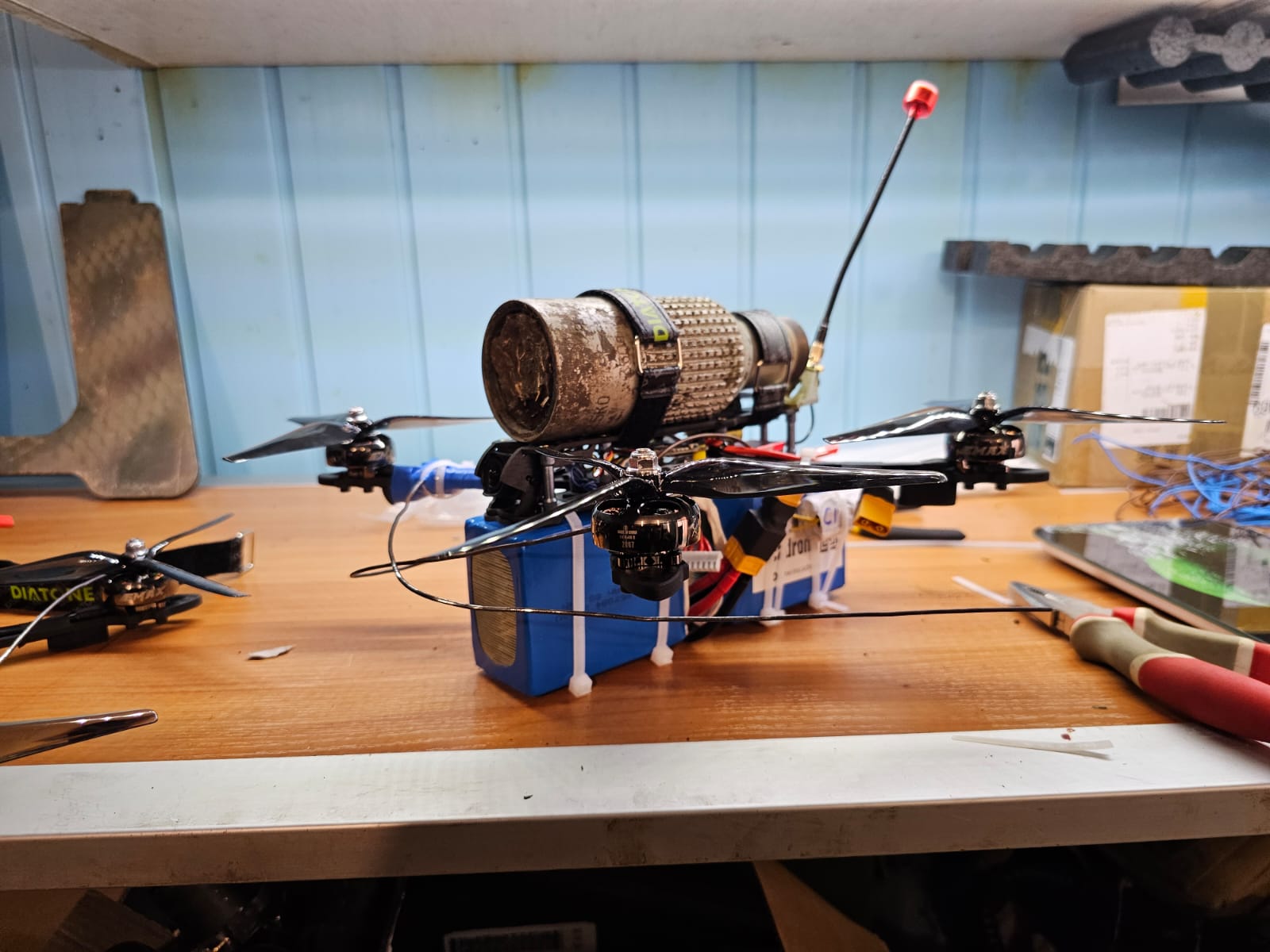

Well-known Mavic “wedding drones” show the battlefield from above on a monitor. FPV drones are different: used by professionals for racing, they stream video directly into the pilot’s goggles for immersive flight.

“That way, you control the situation better, reacting faster to changes. You get immersed in flying,” Vadym, a Ukrainian FPV drone operator of a frontline unit who asked his last name to be withheld, told Euromaidan Press.

Difference between a "wedding drone" and an FPV drone

| Mavic drone | FPV (First-Person View) drone |

|---|---|

|  |

| Flies autonomously when told to go in a certain direction | Do not fly autonomously, require manual control |

| Can hover over an area | Fly fast, up to 72 km/hour, is harder to shoot down, do not hover |

| Camera faces down to capture stable aerial photos and video | Camera faces flight direction for freestyle tricks and high-speed racing. |

| Piloted by line-of-sight while watching the drone in the sky | Piloted using live first-person video feed from the onboard camera to goggles or a monitor. The pilot sees as if they were aboard the drone |

| Can be flown after minimal training | Require highly skilled pilots with extensive training |

| Can carry 0.5 kg of explosives (F1 grenade, VOG-25 grenade, or a self-made explosive system on its base) | Can carry 1.5-2 kg of explosives (two thermobaric 0.8 kg bombs or a round from the SPG-9 gun, allowing piercing heavily armored vehicles |

Small drones are indispensable to the battlefield now.

- They allow soldiers to go 1-3 km behind the contact line, performing fire support, reconnaissance, artillery correction, and identifying casualties on both sides. “For instance, a sniper shoots a Russian from 1.2 km, but doesn’t know if he’s KIA or WIA. We raise a drone and verify that,” Vadym explains. Drones also deliver urgently needed supplies to positions, such as radios, ammunition, or water. In one case, a drone led a woman to safety in a rescue mission.

- Drones provide cheap but highly effective weapons. At the start of the war, artillery, anti-tank launchers, and grenade-dropping drones caused the most damage to Russian equipment. By March 2023, kamikaze and grenade drones were the most cost-effective Ukrainian weapons; FPV drones now hold first place. For $500, an FPV drone can uncover a dugout so that mortars can blast it, take out a T-72, and set a Russian Tor air defense system ablaze. “These are expensive, irreplaceable losses for Russia, difficult to recreate because it requires sanctioned Western technology. One T-72 tank was taken as a trophy: a drone dropped an SPG round, and its crew fled,” Vadym explains. Escadrone’s first FPV hits of Russian armor were in September 2022.

Moreover, drones have now become a key factor for battlefield success. “If we had 300 drones when our battalion's tank offensive was underway, it would’ve been total victory,” Vadym explains.

Drone pilots are now prime targets, but operating remotely is still relatively safe. This is why many Ukrainian soldiers are now lining up to become drone pilots, technicians, or engineers.

How FPV drones are produced in Ukraine

FPV drones in Ukraine use Chinese parts like flight controllers, motor regulators, and communication systems. Frames can be cast or machined locally, as per Vadym.

“It’s like the USSR in WWII: many little garage operations try to produce their own machines for different tasks. Ukraine has dozens of large groups, and smaller ones in each brigade,” he says. His unit is one of the smaller producers, assembling 10-30 drones a month, and more if parts suffice.

One of the largest producers is Escadrone, founded by a pair of investors with a background in finance who saw perspectives in the FPV technology. They donated $8,000 towards 10 drones but did not see results. So they started creating their own cheap and effective drones for the army.

FPV drones should be a method of mass terror. A $500 drone should simply destroy everything that moves.

Escadrone founder Andriy

At first, Escadrone’s founders self-funded producing drones for Ukraine’s units, investing $200,000. Now, the initiative is funded by many other donors who want to invest in Ukraine’s victory.

They cut costs from $800 to $340 per drone by finding the right developers. An expert developed a base model; then, the company scaled production. In August, they produced 2,743 drones; the goal for December was 4,000. The engineers are young, 21-22 years old on average; the oldest is 34. Just one has an engineering degree, but all have strong practical skills. Despite this, Escadrone claims advanced technologies.

“You don’t need a big plant and Ivy League engineers. Combining financing, enthusiasm, and knowledge works,” said founder Andriy.

Escadrone does not create new models but squeezes the most out of existing models. They produce 7, 8, and 10-inch propeller drones, cutting the 7” cost from $500 to $284 with an 8-km range. Larger batteries mean over $500. The 10” one, called “Mammoth,” carries 4 kg for 12 km.

The record distance for an Escadrone FPV drone so far is 23 km with a 1.2 kg payload. This record is likely to increase as batteries, ammunition, and motors evolve.

Escadrone now produces its own drone munitions, as Ukraine lacked the right types. They now produce a 4 kg thermobaric bomb in partnership with other companies, handling licensing.

Liubov Shypovych of NGO Dignitas, which facilitates technological development in the Ukrainian army and runs a drone school, believes Ukraine needs 200,000 FPV drones monthly, more if there are offensive operations. Currently, some 200 producers which supply 10-15% of this.

DroneSpace founder Maksym Sheremet gives a higher estimate: Ukrainian companies manage to produce about 50,000 drones a month; Russia makes sixfold more.

Ukraine faces a drone deficit, Escadrone’s Andriy says:

“FPV drones should be a method of mass terror. They are not Russian Lancets, costing $40,000 and going only after armor. A $500 drone should simply destroy everything that moves. Cars, light, heavy armored vehicles, infantry. We’re seeing effectiveness skyrocket. One brigade uses drones to support assaults: 50 drones fly and destroy everything in the trenches.”

China’s role

In September 2023, under US pressure, China restricted exports of military drones and drone components. This forced Ukrainian producers to rely on complex intermediary schemes to keep acquiring components -- the basis of Ukraine's homemade FPV drones.

“When we order anything labeled ‘DJI for FPV drones,’ China stops it at the border when they see it’s heading for Ukraine. Our procurement routes are now elaborate – China to Bangkok to UK to Ukraine. It’s lengthy, costly, and unpredictable,” Vadym explains.

Meanwhile, the Russians have a carte blanche: China not only allows them to buy these components, they also sell them ready-made solutions, says Vadym.

“If we see China as a partner of Russia, then how do [the USA] expect to hit Russia with these Chinese restrictions? They have a common border; 15 Russian cargo planes fly to China daily,” says Escadrone’s Andriy.

He does not believe that forcing China into sanctions and restrictions will work: “The Chinese are quick and clever. Today you restrict Ivanov, and tomorrow he rebrands himself into Petrov and will produce any brand at the same factory. The Chinese will make money off us, the Russians, and anybody else.”

Escadrone initially thought the Chinese restrictions would not impact FPVs. But in practice, Chinese companies now fear exporting any drones to Ukraine, whether ordered by the Communist Party orders or to avoid problems. Like Vadym’s unit, Escadrone now uses intermediaries in Poland, Vietnam, UAE, etc, raising costs. To Ukraine, it can appear corrupt via shell companies, undermining state deals.

Mass-production over 1,000 drones monthly poses challenges, including component shortages and defective or substandard parts sneaking into the supply chain. This is why a part of Escadrone’s drones come in semi-assembled from China, which Andriy says have better quality control than Ukraine’s fledgling industry. Chinese workers have more experience in specialized roles and better production systems.

However, ready drone flows are easy to restrict, as the September bans showed. China blocks FPV drone exports not just to Ukraine, but Poland and Kazakhstan too, per Andriy. This is why Ukraine must develop domestic production while procuring ready Chinese solutions if possible.

Russian electronic warfare and FPV drones in Ukraine

Evading Russia’s sophisticated electronic warfare is a game of cat and mouse, according to Escadrone’s founder. Jamming brought down 9 of 10 drones in some areas. Escadrone found a solution to the problem, but the Russians will soon get hold of the Ukrainian FPV drones that do not fall, find their secret, and tweak their EW. Then, Escadrone will need to search for new ways to evade.

“The only plus is that we can shift to new gears in a few nights, and their huge military production complex needs a lot of time to come up with countermeasures.

If Ukraine started from cheap drones and is moving to more expensive ones now, Russia went the opposite direction: they buy expensive drones in China and remake them into 10” long-rangers. This was Ukraine’s mistake, Andriy believes: precious time was lost.

Russia still trails Ukraine by 3 months in drone tech but is catching up in skills. “In the future, this will be a huge problem for us,” Andriy from Escadrone says. Russia’s money is the big problem - more multimillionaires funding advanced drones vs Ukraine’s bang-for-buck models, Andriy says. He won't detail Russia's deficiencies - no need to help them improve.

Frontline feedback crucial for fast developing FPV drone field

Vadym's small unit is an R&D operation funded by wealthy battalion members.

"My boss fights with these drones, gives us frontline feedback to improve them. We constantly upgrade as developers, operators, and funders. It's a full cycle," he explains.

Trending Now

The more different approaches there will be, the larger the chances for progress. We can’t standardize drones – if one code’s cracked, all have problems.

Escadrone founder Andriy

This agility keeps them ahead, per Vadym. New tech like block-10 protocols and multi-satellite GPS gets implemented fast. "So our drones now fly farther, are more stable, have better video, and carry more due to efficiency gains."

This contrasts with Ukraine’s state military production giants like Ukroboronprom, recently transformed into a consortium. Requests to make a special bomb would take 1.5 years of checks, Vadym laments.

Agility and flexibility are also key for Escadrone. They have direct feedback from the units they supply, allowing rapidly identifying and solving problems. When Russian EW brought FPV drones in Ukraine down en masse, within one month, Escadrone studied the problem, experimented with the frequencies, and found a fix – something that would be unthinkable when cooperating with the state.

Most Ukrainian drone teams know and assist each other despite trade secrets. Escadrone's founder believes diversity benefits progress: whoever believes in any given technology develops it. The state and the army could want a unified product, but it will never happen: “the more different approaches there will be, the larger the chances for progress. We can’t standardize drones – if one code’s cracked, all have problems.”

Small teams constantly improving custom solutions for specific units are an asset, even if they only make 10 drones monthly: the feedback from the front enables breakthroughs in technological progress.

Escadrone knows each pilot and gets feedback to improve drones. It supplies FPV drones to roughly 100 army units in Ukraine, but only after pilots undergo Escadrone’s training course on theory and repairs, which will help them handle irregular situations.

Then comes practice: “tie a kilogram to a drone and fly around with it from morning till evening,” until pilots are able to land the drone on their feet, take off from their lap.

"Ace" pilots have flown 600-700+ drones. On missions, aces deploy 40 drones simultaneously, shattering Russian armor. They can circle tanks to identify vulnerabilities - first motors, now more penetrable turrets. Any equipment hit is a win, even if not destroyed on the spot - it often retreats for repairs.

Most importantly, hits show Russians they're watched and vulnerable. This erodes morale and motivation as they feel like prey instead of hunters. “They are like sitting ducks, everyone is watching them, they are picked off at ultra-long distances. People with a sense of prey have no motivation to fight."

Meanwhile, drone pilots feel like hunters, sitting protected in a bunker with a control station. Intercepts convey Russian panic over the relentless accuracy of drones - desperate calls to deploy EW and guns to stop the "birds."

Ukrainian FPV drone producers vs. the Ukrainian state

Small producers like Vadym struggle with state cooperation due to bureaucracy hindering defense contracts, including 50% domestic parts requirements -- problematic given the lack of high-tech manufacturers.

Even small orders get stuck at customs for weeks, putting qualified pilots at risk: without drones to fly, they pick up rifles and become soldiers. Sometimes Security Service friends intervene to release shipments.

Escadrone, on the other hand, certified some drones for use with the Ministry of Defense but still faces hurdles. Any parameter change means redoing certification, which takes 3-4 months. By then, the model is outdated as the "rules of the game" change rapidly -- munitions, ranges, EW, frequencies, etc. One 5km drone was useless when finally certified: the average range of FPV drones in Ukraine increased to 15km.

“The state hasn’t switched to a war mode,” Escadrone’s Andriy says. This is why agile and flexible private initiatives will always be ahead of the rigid state in drone production, he believes. The certification paperwork and delays make it hard to keep pace with the quickly evolving technology.

This is why Escadrone has only one small state contract; most drones are funded by private investors, charities, and parent companies like Everstake. "We show 400-500 times return on investment; they're happy to see their funds show results, destroying equipment."

However, Andriy acknowledges issues with Escadrone’s financial model. Money from charities and investors is dwindling as ordinary Ukrainians struggle financially from the war toll. State contracts would increase production, though Escadrone avoids them due to the bureaucracy involved. Working with local and municipal authorities, who increasingly spend tax money on drones, has gone better.

Everyone sees drones work; local communities and the state will buy more. But agile volunteer initiatives, not bureaucracy, enabled the breakthroughs in drone warfare.

“Volunteer groups like ours drove progress. We didn't just say 'this can fly and carry stuff,' we showed results: burnt tanks and howitzers 22km away that artillery can't reach - drones did it," Andriy stresses. This constant video evidence contributed to a paradigm shift among older commanders.

The "Army of Drones" launched in July 2022 is a welcome shift in state-producer relations. For Escadrone, it has acted as an information hub, connecting them with investors, aiding production and use. Run by the Ministry of Digital Transformation, it avoids Defense Ministry bureaucracy. In 2023 it spent $1.07 million on drones for army units. While still insufficient, this is a significant sum, says Liubov Shypovych.

Working with the state is difficult, but Ukraine has no other choice, she says: “We’re in a great war. Private initiatives alone can't win against Russia's regular army, no matter how many private armies we build. As hard as it is, we must move in this direction."

Some initial pilot projects can be private, but later all must scale to the armed forces level. Her Dignitas fund leads by example, establishing a state FPV pilot training program on a military base.

"If we disappear, it will continue. Training more pilots, some becoming instructors, roots this in the Armed Forces so it can't be rolled back," says Shypovych.

The changes are irreversible: even the most Soviet commanders now see drones as essential, Shypovych assures.

At the start of Russia’s invasion in March 2022, drone-users seemed exotic freaks: grenade launchers and machine guns were seen as the real weapons. Now artillery won't fire without a Mavic "wedding drone" video feed. "Those Soviet colonels may not understand the tech, but they want real-time war vision," she notes.

Overcoming limitations and the future

Innovation depends on the right parts, and that is becoming a problem. Apart from the FPV drones themselves, power cells, rare low-loss cables, high-quality connectors for them, components for remote antennas and repeaters are needed, as well as facilities for manufacturing drone components. Vadym's unit makes carbon fiber frames based on modified Chinese models. His dream is a fully Ukrainian drone, but only motors are feasible soon - flight controllers, regulators and video systems lack domestic factories.

Agile volunteer initiatives, not bureaucracy, enabled the breakthroughs in drone warfare.

Some components are already rare with war-driven demand. But Vadym's team improvises, like reverse-engineering flight controllers using Arduino microcomputers and custom software with sensors to mimic integrated functions of an accelerometer, gyroscopes, barometer, processor, payload switches, etc.

Further improvements include a ballistic calculator to calculate optimal bomb drop spots - currently relying on pilot skill. "The biggest problem is that compatible software for our systems doesn't exist," says Vadym.

A major factor limiting the garage-style development of FPV drones in Ukraine is the isolation of the small teams, which prevents building on the achievements of one another.

The isolation of small teams hinders building on each other's achievements. "Some made jam-resistant GPS from Chinese parts and local software. Without involvement, you'd never know, only seeing their drones succeed where yours failed. Most keep developments secret due to competition," Vadym notes.

Bridging isolation is a Dignitas goal via workshops and conferences. "It's important manufacturers don't stay locked in basements but communicate to understand each other's capabilities," says Shypovych. "Maybe one makes basic engines $2 more than Chinese ones – maybe it’s worthwhile for others to buy from this manufacturer, rather than import from China. They want to learn from each other, with one such meeting replacing months of work.”

However, holding such gatherings is dangerous in Ukraine, as they become targets for Russian attacks. Dignitas’ conference for drone producers in Chernihiv was struck this summer, killing seven and injuring 148 despite conspiracy precautions.

"It's understandable why Russia targeted it - to intimidate, inhibit development by stopping communication," explains Shypovych.

Escadrone is working on solutions for drones to lock onto targets and strike independently of pilot skill, like US Switchblades, allowing hits despite EW - but at a fraction of the cost. "Complicated systems doable in a garage, but lots of testing and time needed, especially from scratch by basic engineers," they note.

Perhaps the biggest limitation in Ukraine's drone innovation is the shortage of qualified engineers to drive progress. Before the invasion, little demand existed in the deindustrialized economy, and many experts trained after independence emigrated.

Most Ukrainian engineers were trained during Soviet times and worked on state behemoths; they are smart and qualified but lack the dynamism required for the FPV field, as drone producer Oleksandr Yakovenko told Forbes. He spent months hunting specialists like EW engineers, even abroad.

The engineering deficit is felt more acutely in the field of large, long-range reconnaissance and attack drones – a crucial part of Ukraine’s capacity to strike military objects in Russia amid a Western prohibition on using long-range missiles on Russian soil.

However, drone assembly alone is a relatively basic skill that many can readily learn. This is why FPV producers take on training complete novice engineers - anyone capable of handling a soldering iron can be quickly taught full drone construction and wiring, allowing companies to build talent from the ground up. Dignitas tries to accelerate this process: in the last months, they have released two online training courses for aspiring FPV engineers, which have been promoted by Ukraine’s Digital Transformation Minister Fedorov.

Related:

- Here is a map of all Ukraine’s 2023 drone strikes on Russian targets

- Inside Ukraine’s campaign to crush Russia with combat drones

- Ukraine’s FPV drone production nearly sixfold behind Russia’s amidst engineers shortage

- War of drones: can Ukraine keep its asymmetric advantage?