The dungeons of Orikhiv

In mid-July 2023, I was on a humanitarian mission, which brought me to the town of Orikhiv in the Zaporizhzhia Oblast. The Russians never occupied this town, but since the spring of 2022, it has been in the proximity of the frontline, wholly exposed to Russian shelling.

As a result, almost all town buildings have been damaged or destroyed. In 2020, its population was about 15,000. Less than 10% remain now. Most of them are elderly. Many of them were deprived of electricity, running water, and other basic facilities for over a year. Some time ago, a humanitarian hub was set up, where they could come and receive hot food, have a shower, and watch TV. A few days before I came to Orikhiv, Russian airplanes dropped two bombs and destroyed the hub. Together with those who had come to receive some help there. About a dozen people died, and more were wounded — most of them volunteers and elderly people.

We visited the place where some of these elderly live. Their three-story apartment house is at the town’s side facing the Russian positions. From there, they are being shelled on an almost everyday basis. A Russian cannon had delivered a mine precisely to the door of their building during breakfast time the day before we came. This makes it suicidal to stay in their apartments. Less suicidal is to stay in the house’s basement, where they moved more than a year ago.

I have been to many places of misery, such as the favelas of Rio de Janeiro and the slums of Uganda. Even the barracks in Auschwitz, in my judgment, look more comfortable than the living conditions of the babushkas hiding in the basement underneath their apartments in Orikhiv. Members of this group, the oldest of them in her advanced 80s, spend most of their time surrounded by concrete walls, without daylight or ventilation. They do not have electricity, running water, or sewage. In addition to that, they are being ceaselessly bombarded by the Russians.

I could not resist asking these people: why do you choose to stay in this basement? They have a choice to go to Zaporizhzhia or even abroad. Social workers and volunteers urged them many times to leave for safety. Yet, they told me there was no way they would. They are resolved to stay as close as possible to their homes, whatever it takes, even death itself.

I was first puzzled by their response, but then I realized that it is a metaphor for Ukraine.

My country, in a similar way, did not yield to the overwhelming and seemingly unstoppable Russian forces advancing on Kyiv with plans to take it in three days. The Ukrainians who have picked up the seemingly unwinnable fight and continue fighting regardless of the price are like these elderly people in Orikhiv. They have been urged to give up many times, and yet they are resolved to carry on. If someone disagrees with their decision, we still must respect it because it is their free choice based on rational arguments and moral judgements.

The Maidans

Ukraine emerged from the Soviet yoke with a minimal experience of freedom and self-determination. Joseph Stalin, and before him the Romanovs, made sure that the Ukrainians forgot the traditions of self-governance and decision-making which they had had in the period of the Cossack republic in Zaporizhzhia in the period of early modernity before they became incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Holodomor, the artificial famine of 1932-1933, delivered the strongest blow to the Ukrainian longing for freedom. The Kremlin created conditions that led to starvation and the eventual death of about four million Ukrainians, mostly in the rural areas. Many were bearers of the strong will and agency for political and social action that Stalin wanted to eradicate.

The Soviet dictator managed this, but not completely. Since the independent Ukrainian state was established in 1991, the Ukrainian weakened political agency and responsibility has been growing exponentially. This growth featured several important milestones, which the Ukrainians refer to as “the Maidans.”

Why has Ukraine succeeded as a democracy, contrary to Russia and Belarus?

The earliest of them was the so-called “Revolution on Granite.” It took place in October 1990 and was driven by a group of students. They went on hunger strikes and stayed in tents pitched on the main Kyiv square’s granite pavement — hence is the revolution’s name.

At its culminating point, it brought together dozens of thousands of protesters. They tried to prevent the reestablishment of the Soviet Union through a new agreement between the Soviet republics. Instead, they wanted their country to become independent and de-Sovietized.

At that time, I was in high school and participated in similar manifestations in my own city of Cherkasy, in central Ukraine. I remember this feeling of being a part of a group, which, albeit small, can incur a lot of change.

After many years, I would describe this feeling as an awoken awareness of our own agency. By “us,” a posteriori, I mean the nuclei of the nascent civil society, which would become the strongest player on the Ukrainian political scene.

Next time, I had the same intense feeling 14 years later, during the “Orange Revolution.” It was the color of the presidential campaign of Viktor Yushchenko, with whom most of the Ukrainian civil society identified themselves and their hopes for democratic change. His contender was Viktor Yanukovych, associated with corruption and regress.

In the presidential elections in November 2004, the Central Election Commission of Ukraine gave Yanukovych the victory. However, there was a consensus shared by most international observers and the progressive Ukrainian public that the Commission manipulated the results. Up to one million poured into the Square (Maidan) of Independence in Kyiv, as well as central squares and streets in other Ukrainian cities. As a result, Ukraine’s Supreme Court ordered to redo voting. This time, it was declared fair and awarded Yushchenko with the presidency.

That year, I defended my PhD thesis at Durham University and sometime earlier had started working in Moscow, at the Department of External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate. I was full of ideas that I brought from Britain, where I discovered the power of civil society and learned to appreciate democracy. I saw similar manifestations of people’s own agency in the streets and squares of Kyiv, where I visited my family.

One time, I visited Kyiv with my colleague from the Moscow Patriarchate. I observed that his attitude to what we saw in Kyiv during and soon after the Orange Revolution was different from mine. He looked at it with suspicion. He clearly showed that he did not appreciate the agency of the people.

Later on, he would become one of the key designers of the “Russian world” ideology, which acknowledges the agency of the state only. This ideology wants the people’s agency to be limited to following exclusively the will of the political leaders. If citizens dare to diverge from what the government says, they are manipulated, deluded, or both.

In November 2004, when the protests against the rigged elections started, the wife of Victor Yanukovych, Lyudmyla Yanukovych, held a public speech which became viral:

Dear friends, I am just from Kyiv. I can tell you what is going on there. There’s an orange bacchanalia there! So, there are valenki boots in rows…, and everything is American everywhere! And mountains of orange oranges. It’s just… It’s a nightmare! And I want to tell you that these are no ordinary oranges; they’re spiked with drugs. People take an orange, eat it, and then take another one. And their hands on their own stretch to take another [orange]… And they stand and they stand! Their eyes are just crazy!”

In a nutshell, Yanukovych and his confederates wanted to deliver the following: those who dare protest do this not by their own decision. They are either drugged, manipulated, or bribed. Viktor Yanukovych and his cronies could not imagine that people could come to the Maidan by their own will.

Among many explanations about the origins of such a perception, one is theological. In his native Donbas, Yanukovych began his career as a criminal who turned into a politician. When he reached some political prominence in his region, he converted to Orthodox Christianity. His conversion happened under the influence of a renowned monk, Zosima Sokur, who became Yanukovych’s spiritual mentor.

Zosima’s peculiar spiritual practices and ideas included a complete disbelief in human agency. At the same time, he believed in coercion as the only effective means of achieving the ideals of Christian life. He was also completely anti-Western, anti-ecumenical, and a fervent proponent of Ukraine’s unity with Russia. He said, for example:

“This is what our Rus was like: one, mighty, indivisible. This is how it should be for future generations: inseparable. So that there would be no this Ukraine, Russia… So that it could unite all of us so that we would be a single spiritual family.”

The ideas of coercion and unity with Russia helped Yanukovych to consolidate his power and cultivate autocracy and corruption. Quasi-theological ideals of his spiritual mentor, Zosima, planted in his mind disbelief in society’s own agency.

The same disbelief has been planted in Vladimir Putin’s mind. The Russian leader also has spiritual mentors who believe in coercion and “Holy Rus.” They include the Patriarch of Moscow Kirill Gundyaev and Metropolitan Tikhon Shevkunov. Both are the main providers of religion-based ideology for Putin’s regime.

At the same time, Tikhon’s worldview is closer to that of Zosima. The former often refers to the latter and shares his conspiracy theories that the global West ostensibly seeks to destroy Russia.

Tikhon also actively promotes coercion in both spiritual and political life. His best-selling book, Everyday Saints and Other Stories, endorses coercion as the most effective method of mission, which God himself prefers. Human agency in the book and the worldview of Tikhon is reduced to a minimum.

He reportedly advises Putin on various policies, which helps him to pass his ideas and theories to the Russian president and his circles. Those ideas and theories fall to the well-prepared soil. As a KGB agent, Putin was trained to distrust human agency and to identify either real or imagined manipulations behind political and social developments. The more absolute power he accumulated, the more his distrust developed into paranoia.

Putin’s paranoia about Ukrainian agency

Apparently, a progressing paranoia regarding the growing agency of the Ukrainian civil society constituted a factor that influenced Putin’s attitude toward the events that developed in Ukraine during the winter of 2013-2014. Those events became known as the Revolution of Dignity or Euromaidan.

It was triggered by President Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. Instead, he declared that his priority would be to tighten Ukraine’s relations with Russia. Not only this, but also the galloping corruption and multiple violations of human rights under Yanukovych’s presidency urged hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians in Kyiv and other cities across the country to join the protests. Ukraine’s main square, “the Maidan,” again became their epicenter.

My experience with the Euromaidan was not much different from the experiences of 1990 or 2004: people rose up and began acting with determination and assuredness about their own agency — against all odd circumstances.

This time, however, the circumstances were significantly harsher than earlier. It was winter, with temperatures falling far below zero. Then, there were special police units, especially the infamous “Berkut.” They circumfused the protesters with water guns under below-zero temperatures, organized bands of gangsters to beat those who returned from the Maidan home, and kidnapped people, of whom some were killed in the forests around Kyiv.

The governmental violence culminated in February 2014 when snipers and other units started shooting and killing the protesters. 108 were killed. Later, they were proclaimed the members of the “Heavenly Hundred.” Over 1100 were wounded.

This was the hardest test so far for the resilience and self-determined agency of Ukrainian society. It had to resist not only the troops sent by Yanukovych but also some Western mediators who tried to bring the Maidan’s representatives to the table with Yanukovych. The Maidan, in its majority, booed such attempts. Eventually, everyone complied with the will of the protesters, including Yanukovych, who fled the country.

Vladimir Putin, however, did not see the victory of the Maidan as a manifestation of the people’s will. He read it as a success of the Western manipulations behind the scenes. Russian propaganda began disseminating narratives that confirmed such an interpretation of the events.

For example, a popular conspiracy theory was propelled that the protesters at the Maidan were drugged. It was not much different from how Liudmila Yanukovych had explained the Orange Revolution. This time, however, not oranges but cookies appeared to be at the center of anti-Maidan propaganda.

The story goes like this. On 11 December 2013, a representative of the United States Department of State Victoria Nuland, accompanied by the US Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt, visited the camp of the protesters at Maidan Nezalezhosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. They shared some sandwiches and pies with the people gathered during their visit. The Russian propaganda immediately turned them into cookies infused with drugs that paralyze the will of those who eat them. Not a chance was given to the Ukrainian people to exercise their own will and agency.

As a true believer in coercion as the only means that can effectively change people’s minds, Vladimir Putin waged a proxy war against Ukraine immediately following the victory of the Revolution of Dignity. He annexed Crimea and then sent his “green men” without military insignia to the Donbas area in the east of Ukraine.

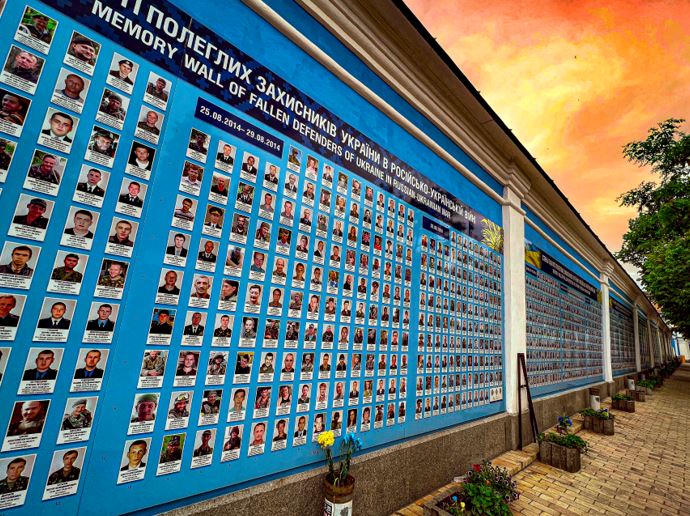

The war began, and it has not ended yet. In February 2022, it just escalated. From February 2014 through February 2022, according to the Ukrainian reports, over 3400 civilians and over 4600 Ukrainian military were killed.

Nevertheless, the Western reactions to the Russian intervention in 2014 were lukewarm. The US and EU introduced sanctions against the Russian economy, which were more decorative. Through the “Minsk agreements,” they tried to force Ukraine to accept a formula “peace in exchange for territories.”

In the meantime, they kept striking sweet deals with Russia, such as the notorious “Nord Stream” pipeline for Russian gas. Like in the case of the earlier Maidans, the will and strong agency of the Ukrainian people were the main driving forces that resisted the Russian aggression.

Affirming the Ukrainian agency

Strong agency helped the Ukrainians to resist the overwhelming Russian military forces after 24 February 2023. Ukraine’s partners had no hope that it would survive the invasion. Yet, a miracle happened.

My explanation for this miracle is civil society, which is aware of its potentiality and self-determination. It had matured during the previous Maidans and reached its highest point during the Russian invasion.

More than three decades of recent Ukrainian history demonstrate a decisive resolution of the Ukrainian people to protect themselves and their democracy. Each time that the pressure increased, the resolution grew only stronger. It seems stronger than the West’s will to help Ukraine, even though Western solidarity has increased dramatically since February 2022.

Although the Ukrainian army, supported by the army of volunteers and the West, has contained Russian advances and significantly weakened his army, Vladimir Putin and his propaganda machine still present this war with Ukrainians being nearly entirely deprived of agency.

According to the Kremlin, the war has been provoked by the West, particularly NATO, and the Ukrainians are just a veil for the Western neo-imperial advances against the “Holy Rus.” Russian propaganda presents Russia, and not Ukraine, as the victim of aggression, while Ukraine is just a passive instrument.

Surprisingly, many of those in the West who sincerely support Ukraine still buy into and retell these narratives. Quite a few secular intellectuals and religious leaders across the globe would agree, to one or another degree, with the formula that the West fights against Russia to the last Ukrainian. The aggressors coined this formula. For example, the Russian Minister of Defence, Sergey Shoigu, as early as April 2022, accused the United States of the intention “to fight until the last Ukrainian.” Some days later, these words were repeated by Noam Chomsky.

In a surprising move, Russia and quite a few Western policy-makers and intellectuals like Chomsky converge in seeing the war as a chess game. For them, the Ukrainians are just pawns on the board: their will, resolution, and agency do not matter. Nothing can be more unfair to the people who every day choose to sacrifice their life and health for the sake of their freedom and the freedom of those who value it in the world.

Therefore, any scenario of peace for Ukraine should be based on what the Ukrainian society decides to do about its own future.

During the Maidans, this society demonstrated its maturity in judgments and resolution to sacrifice anything for freedom. The Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, also demonstrates his understanding of how important Ukrainian agency is. Many politicians in the West have demonstrated the same understanding. There should be a complete consensus on this matter among those who stand for Ukraine.

Related:

- Why has Ukraine succeeded as a democracy, contrary to Russia and Belarus?

- Russian World: the heresy driving Putin’s war