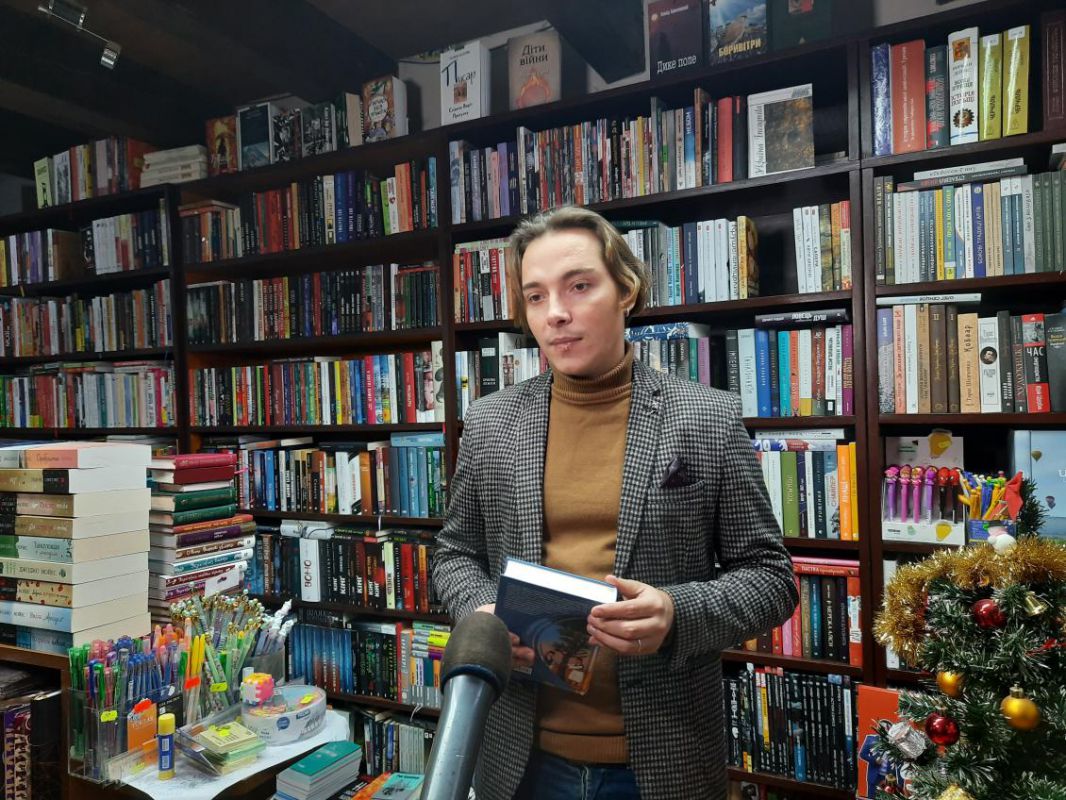

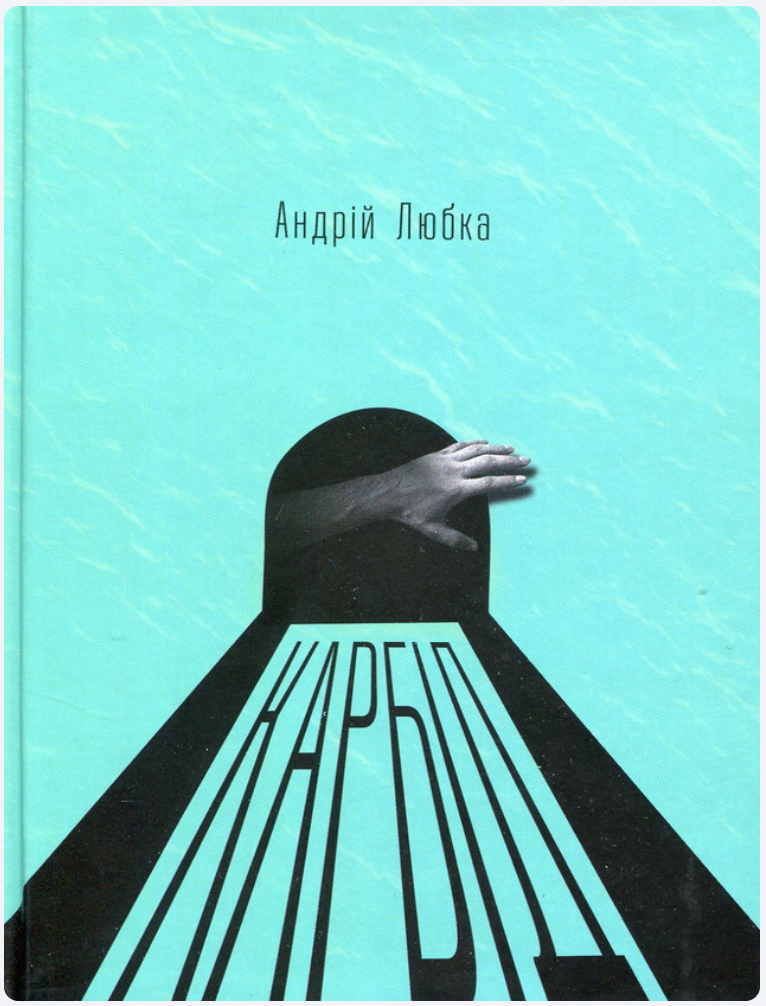

Sometimes, either by fate or serendipity, a work of literature emerges that captures the struggle of a nation at an opportune time and possesses the ability to seize the world’s attention. As the war in Ukraine continues, the need for Ukrainian voices in literature, mainstream media, film, and other fields grows. One such voice is novelist Andriy Lyubka’s, whose novel Carbide provides a satirical take on Ukraine’s European pre-invasion integration crisis, which since 24 February 2022, has made international headlines and logistical headway. With cheeky humor, Carbide opens for readers the in-your-face world of nationalism and the underground realm of corruption and leaves readers even more curious about a country that only 34% of Americans can identify on a map.

Carbide is the raucous, often laugh-out-loud tale of Tys, also known as Carbide–a history teacher in the small Transcarpathian village of Vedmediv, where he lives with his wife Marichka. Frustrated by Europe’s lack of recognition that Ukraine is essentially Europe and Transcarpathia is its center, Tys develops a masterplan: an underground tunnel leading into Hungary through which Ukrainians can travel until all Ukrainians cross the border and are in the European Union. Readers unfamiliar with Ukraine’s complex history and existence with Europe may at first find Tys’s idea rather, well, stupid.

However, Lyubka’s novel portrays a pre-February 2022 Ukraine striving to prove itself to a global community wary of the nation’s involvement in the EU, let alone NATO. Because of this, Carbide opens an international conversation about how established NATO-EU countries treat and work with those nations striving to become not only part of a unified Europe, but also a united, globalist society.

The tense Ukraine-NATO-EU relations portrayed in Carbide essentially no longer exist. It is 2023: the war in Ukraine nears the one-year mark; the Biden administration vows the US will continue to support Ukraine; smaller countries like Estonia pledge entire stockpiles of weapons such as howitzers to Ukraine; Germany has agreed to send Leopard 2 tanks to the battlefields. More significantly, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg believes NATO allies should help Ukraine defeat Russia on the battlefield. During the war, Ukraine has continued making great strides in its reforms by quickly aligning its legislation with the EU’s to ensure that when the war ends, accession negotiations can open.

Carbide, too, highlights another long-standing barrier–apart from Russia’s influence–to Ukraine’s NATO membership–corruption. As Tys endeavors to become the “Moses of Ukraine,” he recruits a few local smugglers, including his obviously questionable friend Icarus, a man determined to thwart the border guards at all costs.

Also joining Tys’s ragtag team is Ulyana Kruk, the femme-fatale coroner who traffics human organs to European black market, and Zoltan Bartok, the tomato-pickling mayor whose adolescent life of toilet paper thievery propels him into mayorhood. The smugglers with whom Tys associates manipulate Tys’s tunnel into a tool for their own means, and unlike Tys, whose obsession is using the tunnel for an improved (and emptied) Ukraine, Icarus, Ulyana, and Bartok see only the hundreds of dollars in illegal monies and goods they can sneak between Hungary and Ukraine. Instead of working towards a better future for Ukraine, the smugglers will instead continue perpetuating the illegal systems that keep inhibiting Ukraine.

Carbide’s depictions of corruption ring all too loudly. Prior to the 2022 invasion, the Biden administration continually emphasized that for Ukraine to join NATO, Ukraine must first improve its political and legal systems. On the corruption index–one of the many scales on which a country’s NATO eligibility is determined, Ukraine ranked 122 of 180 countries, as of 2021. More recently, Western allies expressed concerns about how money they send to Ukraine is being used, and several top Ukrainian officials were fired amid corruption allegations.

Tys highlights for readers how, in many countries only the corrupt and the rich typically have access to passport and visa acquisition, and that such corruption, despite media stereotyping, is not a Ukraine-only problem. Tys reflects on the reasons he does not have a passport, and he believes that “Upstanding citizens will never get visas, because they simply have no legal grounds for them.” He clarifies that if one is “an upstanding citizen with a college degree,” or if one works as an educator and doesn’t steal or break laws, then “a visa is out of reach–applying for one is like trying to lick your elbow.” He also shares that one needs “money in the bank, an invitation, and forged documents–which you can’t get without paying a bribe–so once the Schengen Area began sharing a border with Ukraine, traveling became impossible.”

Carbide focuses on the inequity perpetuated by border restrictions, an inequity established by “European bureaucrats sitting in their fancy Brussels offices” who “set everything up that way on purpose so only rich people could get visas and cross the border.”

Nonetheless, this is another socio-political area in which reality and Carbide conflict. According to European Data Journalism Network, the EU automatically grants residence permits and visas to Ukrainian passport holders, and Ukrainians are given priority for housing and social services. As of December 2022, because of the war, the EU granted Ukraine five “visa-free regimes”— energy, transport, economic, customs, and digital. The years-long project, according to The Odesa Journal, became a reality within 10 months. And, as approximately 18 million Ukrainians face a humanitarian crisis and some 4.9 million have registered under the EU’s Temporary Protection scheme, the International Centre for Migration Policy Development forecasts another four million Ukrainian refugees could enter the EU.

Another warning Carbide delivers is that of unchecked nationalism. In the past five to ten years, far-right extremism has risen not only in Ukraine, but also in other European countries, including France, Iceland, and Germany, and in North American countries like the United States. Far-right extremists pose a threat to any democracy, and Tys’s character transforms from an eccentric history teacher obsessed with the history he teaches to a personified Catch-22, where patriotism, civic concern, and blind nationalism blend to form a stereotype of Western Ukrainians, and in general all Ukrainians, that has continued to fuel Russian propaganda.

This stereotype of the stalwart nationalist stems from harmful ignorance of Ukraine’s involvement in World War II, where a small faction of Ukrainians joined the SS Waffen units to form the Waffen SS Galicia Division. Tys is blinded by his theory that Ukrainian Transcarpathia–and specifically his little town of Vedmediv–is the heart of Europe. His personal desire for Ukraine to join the rest of Europe is altruistic and selfish. At other times, Tys’s desire for Ukraine’s integration seems to be one of genuine concern for the rights and well-being of Ukrainians. Tys, however, envisions that his experience is the universal Ukrainian experience, and in Tys, readers see a man wrecked by despair: “In these parts, dreams fade into oblivion the moment before waking; they fly off people’s eyelids, never to return.”

At the same time that Tys transforms into a warning about blinding nationalism, his observations of the ethnic and cultural make-up of Transcarpathia educates readers about this infrequently discussed region of the world. While Lyubka’s portrayals of the corruption and smuggling permeating every level of Vedmedivite society paint Vedmediv and Uzhhorod as no place any tourist would want to visit, Tys’s historical reflections provide a more diverse society than what readers might initially think exist in the region.

With traces of Proto-Albanian influence the dialect of Ukrainian spoken by the Hutsuls, and with “years of Hungarian rule” that “brought Transcarpathians closer to the Balkan peoples,” what becomes clear for readers is that in this region of Ukraine, a distinct identity, even a distinct origin, weaves a complex cultural and historical web incomprehensible to most Westerners. What readers discover is that the stereotypes, propaganda, and general ignorance they hold or believe do not apply to the people, the region, and the country as a whole. Ukraine as a whole is a diverse nation.

All you wanted to know about Ukraine in one book and on one YouTube channel

What readers have to remember while reading Carbide is that Tys is delusional. His story is a pessimistic, tragic one. Meanwhile, as Russia continues its attempts to destroy Ukraine’s sovereignty from, literally, all of Ukraine’s sides and the skies above, Ukrainians everywhere remain optimistic about their, and Ukraine’s, future. In the face of war, Ukraine continues to make progress in its human rights and anti-corruption efforts. Ukrainian resilience, ingenuity, bravery, and determination inspires democracy-cherishing people across the globe. Nevertheless, Tys’s journey in Carbide is an important one, and the talking points about borders, corruption, bureaucracy, and nationalism opened in the novel are imperative to not only Ukraine’s, but any democracy’s, future.

For Western, and particularly American readers, Carbide is a deep dive into one of the finest works of literature to emerge from Ukraine in the last five years. Reminiscent of the satirical works of Kurt Vonnegut and Voltaire, it’s a great starting point for those just beginning to expose themselves to Ukraine’s lengthy literary tradition. Carbide is unforgettable, a satire laced with a humor that leaves one laughing out loud one minute and then questioning their laughter the next while hoping that Lyubka is already at work on his next contribution to an underappreciated literary canon.

Nicole Yurcaba is a Ukrainian American poet and essayist of Rusyn origin. She teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Nicole Yurcaba is a Ukrainian American poet and essayist of Rusyn origin. She teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Related:

- Eleven books to understand Ukraine’s ongoing struggle: a shortlist by Ukrainian politicians

- The rebirth of Ukrainian literature and publishing: famous contemporary authors and new...

- A view of Ukraine’s Euromaidan revolution from the square

- 8 Ukrainian book illustrators that will amaze you

- 2017 marked the beginning of Ukraine’s cultural renaissance

- War veteran Illia Titko: “My “blood formula” has now been changed forever!”

- Putin’s war in Ukraine looks very different in Pskov than it does...

- Graphic novels on the Holodomor