Winter is upon us, on the frontline, in the cities and steppes, in the villages and forests. It will be one of the most difficult ever. This is a fact. This is what ordinary Ukrainians must endure, keeping the faith and continuing to work and play, attend school and take good care of one another with head held high. Otherwise, how to look into the eyes of the soldiers who haven’t seen their families for months, who risk their lives every day, fighting in the rain-soaked trenches, muddy fields or snow-covered forests?

These are not empty words. We in the rear or abroad cannot imagine what is happening at the front, at “point zero”.

The frontline dugout – a temporary haven

It’s noon and pouring rain. Cold and damp. Noise from all sides. Wet. Loud. Our artillery fires, followed by loud explosions nearby; the enemy returns fire. The tanks roll forward slowly, covering a few inches at a time.

The commander orders everyone to take cover. We climb into a small dugout. Water and mud under our feet; the sleeping mats and wooden boards disappear below the rising muck. Sometimes, our guys huddle together and sleep here six at a time. They say it’s warmer that way.

We hear a rustling noise. A mouse! It runs into a small recess on the wall and disappears. The guys joke that they’ve domesticated the mice around them. They’re used to them now and no longer jump at the sight of a column of little creatures scurrying along the ground.

It rained all day. At one point, it was difficult to move. We sank into the thick sludge, our legs slipping and sliding uncontrollably. Each step was difficult. And the penetrating cold. Our clothes clung to our shaking bodies.

But, when it snows and freezing temperatures hit all regions, it will be much harder for everyone. Perhaps it will be easier for the military hardware and vehicles to advance and keep up the momentum, but our men and women will have to affront the cold, deal with freezing fingers and toes, howling blizzards and thick snowstorms.

Today, our soldiers press on from village to village; it’s a fact. But, the most difficult phase is yet to come.

(adapted from Liberov photographers . Kostiantyn and Vlada Liberov are Kyiv-based photographers currently working on the frontline of the Russian-Ukrainian war.)

Who are they, the men and women on the frontline?

Not one Ukrainian wanted this life.

Some, like Sheva, a legendary tanker, was a senior freight handler in a large Ukrainian company before the full-scale invasion. Some like Suieta, Sheva’s comrade, had his own small business.

Some were teachers, professional athletes; others - construction workers, cooks, musicians, IT geeks, designers, realtors, photographers, journalists, salesmen, engineers, musicians, doctors.

Thousands of different people from different walks of life, different professions, different life styles. Thousands of men and women whose lives have changed because they followed their conscience.

Their lives were completely different, far from violence and cruelty, but they took up arms to defend their country and protect their homes. None of them are killers, but they learned how to carry a gun, point and fire at the enemy.

However, their hearts and souls are not soiled by the dirt, pain and cruelty of war. Of course, war leaves its mark, but this doesn’t change the essence of a soldier’s being.

(adapted from Valeriy Puzik, a Ukrainian writer, artist, director and screenwriter from Odesa. Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Puzik has been serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. He carries his paints with him everywhere and creates colourful artwork on ammo crates and discarded boxes.)

Body bags in the setting sun

As I fly my drone over a village under siege, I see something strange and out of place: behind the school building, the Russians have arranged several rows of black bags. The size and shape leave no doubt about their content. I stop the drone and count quickly - fourteen or fifteen.

Someone has lined up the bodies of Russian soldiers, each of whom travelled hundreds of kilometers to get to Ukraine… only to end up lying in a nameless Ukrainian village in black polythene body bags for several days, waiting for someone to come and take them away.

They will wait a few more days until the weather turns really cold. Then, the temperature will rise again for another two-three days, and the freezing weather will disappear, even at night. Then the Russians, who have set up their positions in the school basement, will be hit by the stench of rotting bodies.

The steppe wind whistles through the empty village streets; the body bags flutter silently in the strong gusts as if begging to be liberated.

The rays of the setting sun penetrate the wind, painting everything in a radiant yellow-orange hue. Covered with this reddish golden tone, even the scorched, ruined buildings, where we take shelter, look beautiful.

I gaze at this scene, drinking it in with my eyes… because I know that there are only a couple of clear days left, and then the earth and sky will be hidden by rain, snow and fog.

(adapted from Ihor Lutsenko, a Ukrainian politician and journalist. In 2014, Lutsenko was elected to the Verkhovna Rada. In May 2022, he was awarded the Order of Courage for his actions as a drone operator in deterring Russian aggressors during the battle of Kyiv. He currently serves somewhere in eastern Ukraine.)

Our frontline Grads: old weapons on high-tech battlefields

There are clashes every day. Difficult and bloody battles.

It’s quite spectacular to see the Grads at work - truck-mounted self-propelled multiple rocket launchers designed in the Soviet Union and used extensively by the Ukrainian Army.

But, it’s difficult to find new firing angles. Designed to deliver its munitions over an area rather than a point target, the Grad is not a precision weapon. Grad rockets, often fired in salvos, make a very distinctive low rumble. Within seconds, a Grad rocket launcher can fire off 40 rockets, raining them down like hail (Grad = hail in Ukrainian). But, the closer you come to the weapon, the greater the risk of a small but serious injury from flying plastic fragments.

The commander issues the location of the target to his men. They aim, fire and leave immediately. Grads don’t stand in one place for long, as the enemy quickly pinpoints their position and returns fire, seeking to destroy them.

Believe it or not, it’s a beautiful sight. A strange word to use in this context. But, the evening light is really amazing: incredible colours, a soft sunset, the power and fury of our war machines.

Suddenly, we hear a deafening roar above. We look up and see a fighter jet. Everyone freezes… enemy aircraft often operate in this area.

But no, it’s ours. A beautiful sight… really beautiful!

(inspired by Liberov Photographers)

Old man Kostia

Our guys walk by, coughing and rubbing their tired, bloodshot eyes.

Water boils in a cup.

Tea with lemon is highly recommended. Some kind of virus and high fever are hitting the men.

I catch myself thinking that I don’t see them as soldiers. Not military guys, not soldiers, but beekeepers, farmers, builders, photographers, marketers, drivers, etc. Real people, not just some guys in pixel uniforms. People who were forced to take up arms. People who dream of returning to the world they’re used to. But, they can’t.

None of them wants to fight. Or should I say: no one wanted to. But, they’re forced to do it now: dig trenches, chop wood, move forward, risking their lives, and learning how to kill Russians. Everyone is full of anger and hate.

When these guys open up and talk, you don’t hear pretentious phrases that are so popular on the Internet. You don’t hear whining, inspirational statements such as: “The light within us” or “Hold the line!”

They clench their fists, grit their teeth and continue working… senseless physical work, pushing themselves to the limit of their capabilities.

Sleeping two or three hours a week - no problem. No signal - no problem. Health problems - of course. But, what the fuck, victory is ours!

Through gritted teeth. Every day. Morning to night. Joking and smiling.

Kostia, soaking wet, runs inside to change his clothes and hang them up to dry. He does it quickly, shivering in the cold, illuminating the corner of the room with a pocket flashlight.

-Here’s your poncho, old man.

-Here are your pants. Put them on.

Kostia mumbles a quiet “Thank you” and pulls on the pants.

Max looks into a box, takes out a pair of socks that some volunteers gave him.

-Take a couple, man. You may need them.

-And here’s a pair of army boots.

He pulls some boots out of the box.

-And those socks are really great. They go right up to the knees.

-The water’s boiling. Want some tea?

-Sure, thanks.

- When I get home, continues Kostia, sitting on a tree stump near the stove, - I’ll lie on my bed all day. I have a really cool bed. And everything’s clean. The bedspread, the sheets, the pillows. I’ll go to bed naked. Uh-huh. I’d turn on the lights, but our house chat says there’s no electricity. Although I’m sure it’s fine by candlelight.

Kostia talks a lot. Too much. Sometimes we wish he’d just shut up. He even mumbles in his sleep.

Kostia sips his steaming tea. He throws some wood on the fire.

- Hey there! Hey, old man, There will be smoke all over the place.

- As long as it’s not cold. At least not tonight.

- So, you’ve decided to sleep in your birthday suit?

The boys burst out laughing.

- That’s not gonna work, old man.

- Nah, not tonight, guys. Nah, - he puts the mug down on the stump, - A couple more hours and I’ll be in my warm bag, sleeping like a baby.

- Like a young Greek god…

- Come on already...

The rain seems to have stopped.

Kostia sighs heavily, picks up his weapons and goes outside.

Wet clothes hang on a rope. From time to time water drips on the boot-trampled muddy ground.

(adapted from Valeriy Puzik)

Kurakhove, Donetsk Oblast

It’s biting cold. The wind carries the dry remnants of summer along the street. The bust of Pushkin, the Russian poet with thick sideburns, still stands on the pedestal, whereas the building opposite collapsed some time ago from heavy Russian shelling.

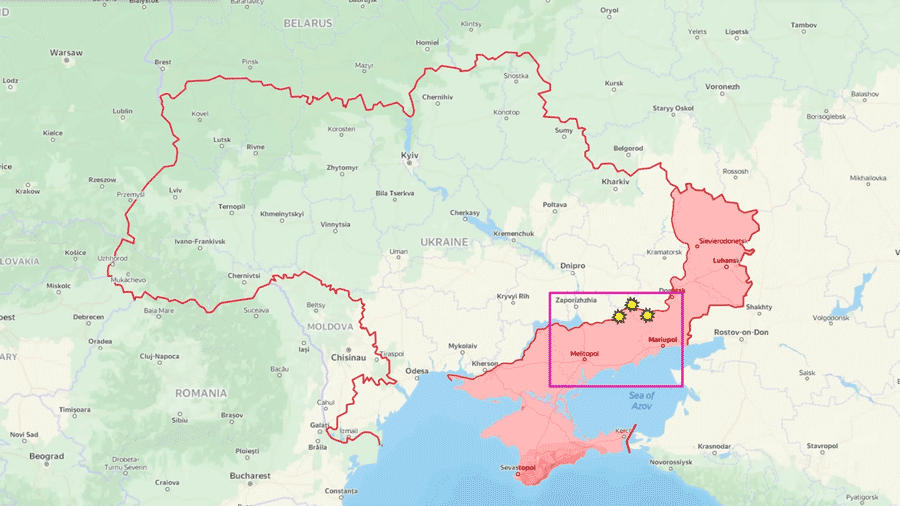

The frontline hasn’t moved much here since the full-scale invasion in February. A few miles to the east is Donetsk, a major city captured by Russian troops and Russian-backed forces in 2014. Moscow has since annexed that territory, and bombards the Ukrainian side with artillery in an attempt to claim more of what it calls the "Donetsk People's Republic".

Half an hour ago, several shells exploded in the city centre. In one of the shops, a local asks the sales clerk where it happened.

“I didn’t hear anything!” she replies sincerely.

I enter another store, and they also ask me. I ask the saleslady where it landed. She sighs deeply.

“When I heard the explosion, I fell to the ground… right here!” she points to a tiny place between the counter and the wall.

A few weeks ago, shelling killed two soldiers nearby. They’d been through hell, some of the fiercest battles, but death caught them in the rear.

The open-air swimming pool in Kurakhove is filled with water. The pool, they say, is one of the best in Europe.

I listen, wondering if this is all a dream. The Kurakhove thermal heating plant is now a key target in Russia’s campaign to obliterate civilian infrastructure, particularly the power grid. The Kremlin is trying to weaponize the winter season and sap morale by plunging Ukraine into a cold world of obscurity.

(adapted from Ihor Lutsenko)

Vuhledar, Donetsk Oblast

War in winter and war in summer are two completely different wars.

The windows of Vuhledar whistle all the time. The wind hunts for the warmth of our bodies; if you stand still too long, life drains quickly from your arms or legs. It takes time to restore movement, to drive away the cold paralysis.

For a person who freezes slowly, it becomes difficult to think, the will weakens; an endless winter covers the future.

In Vuhledar, there are no problems with electricity, because there’s been no power for a long time.

The enemy also suffers. I saw how right along the frontline the Russians lit a fire in a portable stove. Apparently, they believe the steppe cold is more dangerous than our artillery fire.

But I remember something else…

The road to the front passes the graves of my relatives who died some 80 years ago during the Holodomor. In my imagination, I see them watching me from above as I continue fighting a war which started hundreds of years ago.

They say to me: “The cold you endure isn’t as harsh as the cold of the 1932-33 winter. The weapons in your hands are a thousand times better than what we had. You are the part of our family, against which their weapons will crumble and fall. Though you are not the strongest among us, your hands carry both life and death.”

(adapted from Ihor Lutsenko)

Read more:

- The untold story of the first battle for Kherson

- From retiree to millionaire: 7 stories of heroism during the war in Ukraine

- He was a Putin fan. Then Russians bombed his house

- Russian war crimes in Katiuzhanka: torture chamber, toilets in classrooms, and stolen lingerie

- Cruelty, murder, and destruction in Bucha

- Killed for refusing to shout “Glory to Russia!”: Russian war crimes in Trostianets

- The Ukrainian Aleppo, or unprecedented terror in Borodianka – Dispatch from Ukraine