The odor of mass graves

“The stench of decomposing human bodies is the worst smell any living person can ever experience,” said Don Arleth, an American journalist working for a Polish TV channel TVP World, after visiting Izium mass graves.

https://twitter.com/euromaidanpress/status/1573400548245929985

“This smell is very intense, and it is very difficult to be near decomposing bodies, even for a few minutes. The mask does almost nothing to help. Even thirty minutes after we left the area of the exhumation, that nauseating smell persisted and I wanted to erase it with another smell. You wonder how forensic pathologists and the police worked on that site for hours, days,” said Ihor Krut, a Ukrainian-Canadian photographer.

“The smell of death and rot is reminiscent of the smell of spoiled meat or rotten garbage. Dead smell, in a nutshell,” said Viсtoria Streltsova, a journalist and anchor for 1x1 Ukrainian channel who shared that she had to wash her clothes, backpack, and shoes after the first visit to the mass graves and aired everything at the balcony to get rid of the smell.

A combat veteran with experience of working at mass graves in Bosnia suggested using Vicks ointment for individuals attending the exhumation of burial sites. Respirators and masks were recommended by the Kharkiv Media Hub but, according to most journalists, did not help. Slices of orange brought to the site failed to erase the odor. A Ukrainian Orthodox priest, present at the site, waved an incensory over the bodies and standing right next to him brought a short-lived relief. The staff and police working on the site were chain-smoking.

I found the scent was sickeningly sweet, strong, like spoiled soup or cough syrup, and felt viscose, gooey, and it got into every pore. Although I don't smoke, I had to smoke a cigarette at the site. I could feel the smell underneath my fingernails and even on my silver rings a week later. I had to buy a cheap perfume at the bus station to sniff it to get rid of the memory of the odor. I wrote about it and had a therapy session dedicated to the experience but the odor lingered in my mind.

What’s in a smell?

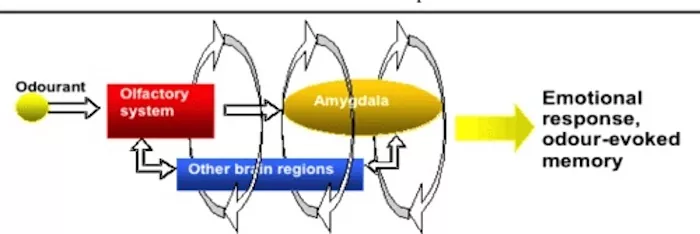

When we experience scents, the molecules floating in the air enter our nostrils and hit sensory cells, called olfactory sensory neurons. The neurons deliver electric signals to the olfactory bulb in the brain. The olfactory bulb is connected to the amygdala and hippocampus, areas responsible for storing all memories, including trauma, and to the limbic system regulating emotion. Thus, the brain converts the sensation of smell into perception.

Scientists proved that odors can trigger emotional memories and responses, just as sounds and visual stimuli.

Some scents can evoke pleasant memories, a phenomenon known as Proustian, called after a famous scene with a madeleine cookie dipped in tea bringing back childhood memories. When mom bakes a pie, the child associates the scent with comfort and will carry this association through life.

Other scents bring back traumatic, intrusive memories and flashbacks. If orchids were placed in a coffin at a funeral, the scent of orchids can cause negative emotions, commented Ukrainian-American perfumery expert, a graduate of the prestigious Grasse Perfumery School Olga Zubareva in an interview with Euromaidan Press.

Sensations known as olfactory hallucinations and odor-related fear and anxiety open a whole other can of worms.

People suffering from PTSD often associate odors with specific traumatic events. In a military hospital in Odesa, wounded Ukrainian soldiers request air fresheners and deodorants more often than food or hygiene goods.

“An emotional memory, like the smell of home cooking, can trigger feelings of comfort, while for those with PTSD, an odor associated with a traumatic experience can trigger a negative response and PTSD symptoms,” commented Dr. Filomene G. Morrison, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School.

There is insufficient scientific data on the subject.

“One of the ways that the brain codes trauma is by increasing sensitivity to the trauma cues in the environment and these tools make it tractable to understand how trauma is encoded. Nothing has been done in this particular realm—one that looks at the structural changes of the brain—particularly of the specific sensory representations associated with fear or trauma and how they change with regard to extinction or recovery from fear,” said Kerry J. Ressler, MD, Ph.D., Chief Scientific Officer and Chief of the Division of Depression and Anxiety Disorders at McLean.

The lasting quality and persistence of the decay odor have a simple explanation.

Smells are a mixture of molecules. The larger the molecule, the fewer chances it will be oxidized. For instance, citrus scents have small molecules and evaporate swiftly, while musky and synthetic fragrances with larger molecules stay on the skin for hours and even longer on clothes and paper where there is no reaction with the skin, and no effect of temperatures, fats, and hormones. Plus, there the porous cloth structure allows molecules to penetrate deeper and the effect of oxygen is further reduced, explained Olga Zubareva.

“Thin fingers raised like a final plea for help.” Exhuming the Izium massacre

“The horror, the horror”

There is a scientific theory of the acute reaction to the smell of dead bodies. Research showed that humans, just like many other species, might be programmed to detect putrescine and cadaverines, chemical compounds produced by the breakdown of fatty acids in the decaying tissue of dead bodies, and perceive them as threat signals. “Necrophobic behaviors” such as avoidance of exposure to pathogens and danger, alertness, or fight-or-flight response, could be deeply ingrained survival mechanisms.

"Humans have likely long been aware that the odor of a decomposing animal is altered following death and that this odor can attract vertebrate and invertebrate scavengers. Homo ergaster (primates, Hominidae) and Homo erectus (primates, Hominidae) would relocate their butcheries away from settled populations to avoid attracting competitors and predators. [...] Carrion flies are not just considered as annoyance pests; they are also notorious vectors that can transmit numerous human and animal diseases caused by many deadly antibiotic-resistant zoonotic pathogens," write the authors of Odor of Death: An Overview of Current Knowledge on Characterization and Applications in BioScience, Vol. 67, Issue 7, July 2017.

“For an individual who does not deal with decaying bodies professionally, exposure to death on such a scale is severe trauma, a psychological shock. And the smell affects us on a subconscious level. The brain perceives this smell as a serious danger. Most likely, a person will be subsequently haunted by a phantom smell,” said Zubareva.

Apart from basic survival instinct, our reaction might be caused by a more complex psychological factor. The decay odor might be associated with existential trauma. A person confronted with the smell of dead human flesh faces the inevitability of physical death, the classic Freudian death anxiety. It is easier to make an abstraction of the sight or sound, theorize, rationalize or dissociate them as opposed to the smell which is purely physical and withstands analysis.

Moral injury cannot be dismissed. Journalists, observers, diplomats, and workers exposed to the mass murder sights are confronted and need to process the inhumanity, the horror that leaves most humans at the loss of words. Moral injury is described as the damage done to a “person’s conscience or moral compass by perpetrating, witnessing, or failing to prevent acts that transgress personal moral and ethical values or codes of conduct.”

Claud Wild, the Ambassador of Switzerland in Ukraine, who arrived at the burial site with a delegation of EU diplomats, said in an interview:

“What we see here—there are no words. […] It is very important to document what is happening here so that those who did it don’t get away with it. We are in front of war crimes here.”

Matti Maaskias, EU Ambassador and the Head of the EU Delegation in Ukraine echoed this sentiment:

“What we have witnessed here today, at this mass burial site, in Izium, has signs of the most heinous war crimes. These war crimes must be tried in court, and, after a visit to this site, for which one has no words, it is clear that the international tribunal must be established as soon as possible and the perpetrators must face the trial.”

Related:

- Bodies of victims in deoccupied Izium are mutilated, have severed genitals – deputy minister

- Mass graves in liberated Izium: Photo report

- “Thin fingers raised like a final plea for help.” Exhuming the Izium massacre