As of 20 June 2022, over 1.2 mn Ukrainians, according to Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine Iryna Vereshchuk, were forcibly transferred to Russia. The top officials of the European Union and the world's leading human rights organizations have urged Russia to stop the unlawful filtration of civilians in occupied territories. One possible outcome of this process is forced deportation, which violates international humanitarian law (IHL). Let's examine Russia's unlawful filtration system in the eastern and southern parts of Ukraine and the plight of civilians currently held/detained in Russia's filtration camps.

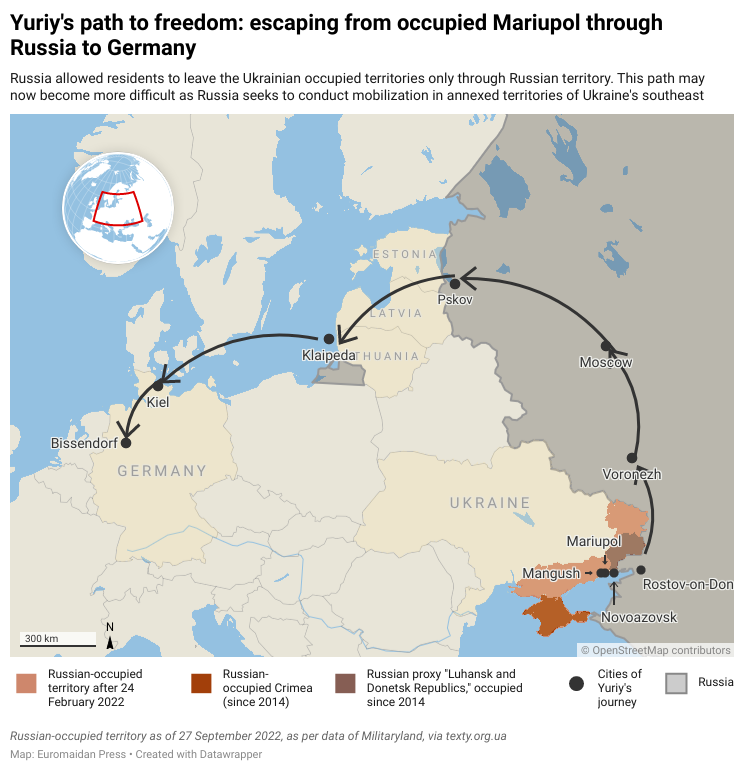

Escaping occupied Mariupol via Russia after "filtration"

During the last century, a part of Russia's war policy has been not only gaining victory on the battlefield but imposing terror against civilians and destroying peaceful cities and villages.

Since the first days of the large-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces have started to block Ukraine's Mariupol. They shelled Mariupol's residential areas and evacuation convoys. Consequently, the heavy bombardments inflicted irreparable damage on water, gas, and electricity supply facilities. They also razed 90% of the buildings in the city.

"At first Russian soldiers allowed civilians to leave Mariupol. I guess the idea was to let as many people as possible out to 'clean up' the city," Yuriy, a former Mariupol resident, told Euromaidan Press.

He successfully escaped occupation and now lives in Europe.

One day, several rockets hit and damaged his house.

"Only because we hid in the bathroom we survived. We quickly took the most important things and documents and left the building. When we got out, our house was already in flames," Yuri recalled.

Then, sometime later, fighters of the so-called Donetsk People's Republic, an illegal state within Ukraine recognized by Russia, began to rule the city:

"It's hard to explain... but they were, in fact, simply thugs and bandits. They could stop a civilian car, force people out and take the vehicle and shoot them."

"DNR" ("Donetsk People's Republic, a Russian proxy state in eastern Ukraine) and Russian forces blocked all the communication services. Zoom, the video platform, was also stopped as a part of sanctions imposed on Russia. According to Yuriy, he had to stand in the queue for two months to get a starter pack of the only Russian mobile operation in the city.

As life in Mariupol became unbearable, Yuri and his family decided to come to Manhush, an urban settlement 20 km away from Mariupol, and wait for liberation. "There was at least some food. Cereal grains…" Soon, they realized fighting was far from over and concluded they needed to leave the occupied zone.

Yuriy and his family were not forcefully deported to Russia. However, they needed to undergo a filtration procedure to receive a pass to evacuate to Russia. Yuriy says that during the filtration, men needed to show their tattoos as Russian soldiers were looking for supporters of Ukraine, including Ukrainian law enforcement employees and military personnel.

While checking their belongings, the invaders found contacts on his mobile phone with profile pictures with Ukrainian symbolics. Then Russian soldiers interrogated Yuriy for 45 minutes.

"Do you know that it was the Azov Regiment [a special unit of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, one of the main 'enemies' of Russia and icon of Ukrainian resistance] that destroyed most of Mariupol?" Yuriy shares examples of the questions.

He was saved due to his job -- he is an online teacher of the English language. Yuriy said his clients lived in different countries -- some in Ukraine and some in Europe. The soldiers handed him the pass documents and allowed him to evacuate to Russia.

Russians did not offer Yuriy and his family a center for refugees or a temporary home upon entry. They had no Russian bank card, internet connection, or GPS navigator to reach their next destination -- Taganrog city, located more than 100 km from Manhush.

In Taganrog, Yuriy had a place to stay - he knew one of the Mariupol refugees who found accommodation there.

"Russian forces isolated the left bank of Mariupol. Residents could only evacuate to Russia from there," Yuri says.

Then, he contacted Russian volunteers, who helped Ukrainians return to Ukraine or find a place to live in Europe.

"Volunteers created the full (evacuation) route for us. They booked a hotel on the way and helped to cross borders. We passed through three countries in one day."

Yuri is endlessly grateful to the volunteers and says they even cooked borscht (a traditional Ukrainian meal) for the refugees:

"If they didn't help us, I couldn't have imagined what to do."

Now Yuri and his family are safe and live in Germany.

Deportation of Ukrainian children: an intrinsic part of Russia's genocide

According to Russian officials and media, there are currently over 628k Ukrainian children in Russia. However, it is impossible to verify this information. The Russian military has consistently denied the representatives from Ukraine and international human rights organizations full access to the filtration camps and transfer centers set up in its occupied territories.

According to RBC Ukraine, citing Aksana Filipishina, a spokeswoman of Ukraine's Ombudsman office, Russia is yet to respond to formal inquiries on the deportation of children.

Consequently, Ukraine has launched its inquiry. On behalf of the Office of the President of Ukraine, the Ministry of Reintegration and the National Information Bureau developed the "Children of War" platform.

This program provides up-to-date information on children that suffered from Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine (killed, injured, missing, deported) and those who were repatriated. It has tracked 7.8k instances of children who were deported to Russia since 24 February 2022, but only 55 children returned to Ukraine as of 16 September.

As of 16 September, 7.8k children have been deported to Russia since 24 February, and only 55 children have returned to Ukraine.

Among them is 10-year-old Illia. When Russian forces began heavy strikes on Mariupol, he and his mother, Natalia, were residing in the city. During one of the devastating bombardments, Natalia severely injured her head, and Illia almost severed his leg as they fled to a neighbor's apartment to escape the shelling.

Despite agony and exhaustion, Natalia had to carry Illia to the flat. They hugged each other as they lay down on a couch. Natalia was cradling her son till her last heartbeat. She passed away in her son's arms.

The following day, Russian soldiers came for the boy. They took him to the occupied city of Novoazovsk and after to Donetsk. Local doctors thought he needed amputation as his leg was badly wounded. They later discovered that the leg was still functional.

In the meantime, Illia's grandmother, Olena Matvienko, was looking for every possible way to return her grandson. At the same time, Russian officials intended to deport Illia to Russia and find him an adoptive family. Olena has finally gained custody of Illia and had to travel across four countries to bring him back to Ukraine.

Meanwhile, on 30 March 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree easing the adoption process of Ukrainian children. This regulation makes it easier for Russian families to adopt "orphans from Ukraine" and the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics. It also makes provisions enabling new parents to alter Ukrainian children's names, dates, and places of birth.

This means that the youngest Ukrainian children may grow up unaware of their heritage.

On 23 August, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) of Ukraine reported that Russia had forcibly moved more than 1k children from Mariupol to the Russian cities of Tumen, Irkutsk, and Kemerovo. Additionally, Russia held 300 children in specialized facilities in the Krasnodar Krai.

There was a recorded case of deportation of minors to Belarus, said Natalia Yashchuk, a coordinator for the Center for Civil Liberties, in a comment for RBC.ua.

In March, when parts of Kyiv Oblast were still under Russian occupation, two Ukrainian brothers visited their sister. They stumbled upon a Russian checkpoint on the way back. Russian soldiers captured and forced them into armored vehicles, put black bags over their heads, and tortured them.

When the invaders learned that one of the siblings was under 18, they deported him to an orphanage in Mazyr, Belarus. It took him a month to return to Ukraine. The Russian occupies reportedly moved the other sibling to the Taganrog detention facility #5 in Russia's Krasnodar Krai, and thus far, his exact whereabouts remain unknown.

The US Department of State and Yale find 21 Russian filtration sites in Ukraine

On 25 August, the US Department of State (DOS) urged Russia to "immediately halt its filtration operations and forced deportations and to provide outside independent observers access to identified facilities and forced deportation relocation areas within Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine and inside Russia itself."

The statement issued by the DOS also included a reference to the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab (Yale HRL) report issued by the Conflict Observatory detailing Russia's war crimes and other atrocities committed in Ukraine.

According to the report's findings, Russians have set up a filtration system weeks before the invasion. This system "likely grew following Russia's capture of Mariupol in April for the filtration of all citizens."

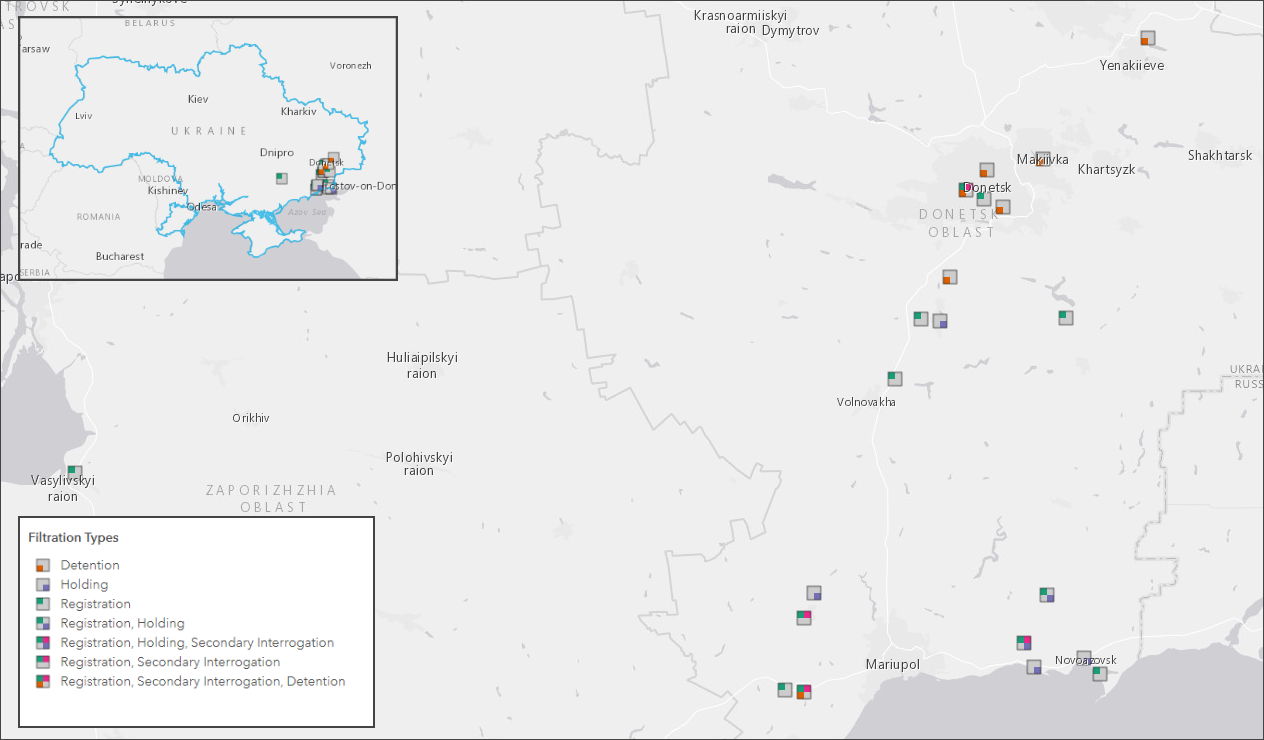

In addition, the report indicates that Russian and Russia-aligned forces run at least 21 filtration sites of four different categories of facilities in and around Donetsk Oblast. These facilities are engaged in the filtration of Ukrainian civilians: registration, holding, secondary interrogation, and detention.

The findings were based on high-resolution satellite images and multiple accounts from victims of unlawful filtration. Here are some examples:

Filtration camp in Bezimenne village, Donetsk Oblast: torture and interrogation

A filtration camp in the Bezimenne village of Novoazovsk Raion, Donetsk Oblast, where Ukrainian citizens are forced to undergo a horrifying filtration process leading to detention, interrogation, beatings, and forced deportation to Russia, was described by BBC.

In March, Vadym, 43, a former employee of a state-owned company in Mariupol, claimed that Russian occupiers had tortured him in the Bezimenne village, Novoazovsk Raion, Donetsk Oblast.

According to him, Russian soldiers questioned his wife after discovering she "liked" the Ukrainian army's Facebook page. They also retrieved the proof of her contribution receipt to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU). Russian interrogators struck down Vadym multiple times upon his attempts to defend his wife. He later regained his feet, but they continued to beat him. Vadym described it as a repetitive pattern, an attempt to "re-educate" him.

After that, Russian soldiers discovered where Vadym worked and moved him to another facility. He claimed that Russian soldiers kept interrogating and beating him and asked him 'dumb questions. Based on Vadym's account, the Russian interrogators kept electrocuting him to the point that he nearly died. Russian soldiers knocked out his dental fillings, Vadym fell and choked on them, then he vomited and passed out. Russian interrogators were enraged. When Vadym regained consciousness, they commanded him to clean up the mess and carried on with his electrocution.

Filtration sites in Kozatske and Bezimenne villages of Kherson and Donetsk Oblasts: registration and detention

News outlet VSE told about the filtration sites in Donetsk and Kherson oblasts - concentration camps of the 21st century. Russian occupiers forcibly transferred the surviving residents of the destroyed city of Mariupol to the detention camps. The survivors underwent registration, holding, detention, torture, interrogation, exploitation, and forced labor.

Nearly four weeks ago, the Russian occupiers forcefully evacuated all the civilian men from Huhlino, Myrnyi, and Volonterivka districts (in Mariupol). They forcefully moved about 2k people to the Bezimenne and Kozatske villages. The official reason is filtration. Russian occupiers banned personal belongings and confiscated passports and other personal identification documents. The first casualty occurred in the Kozatske village due to the occupiers' refusal to call an ambulance.

Filtration camp in Starobesheve village, Donetsk Oblast: daunting images -- a state of absolute deprivation

A report in Meduza tells about how the Russian system of filtration camps for Ukrainians operates. And what happens to those who "failed" filtration?

Russian soldiers initially told Oleksandr's family that leaving for Russia "just like that" was impossible. The nearest filtration site was in Starobesheve, a village in southeastern Ukraine held by the so-called LDNR occupying authorities. "The days at Starobesheve were hellish," recalls Oleksandr. The occupying authorities placed women with young children in daycare. And they housed the rest in some recreation center. The occupying authorities forced all of them to sleep on the ground. There was no restroom at the filtration site, and the only functional toilet was outdoors. Oleksandr explained that it took approximately a three-kilometer walk to get to the cafeteria, where one could eat for free.

The so-called LDNR occupying authorities detained Oleksandr in the filtration camp for three days. They interrogated him about his ties to "extremists," namely Ukrainian military forces, activists, or law enforcement officers. After this, they issued Oleksandr a "travel ticket" to Russia.

Russia's accountability issue for its crimes

The Russian political and military leadership has established an unlawful filtration process for Ukrainians. This action is a flagrant violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention on protecting civilians and a war crime.

At the same time, the Rome Statute serves as the fundamental legal framework of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Under the Statute, the forcible transfer of children initiated by Russian occupying authorities is classified as both a crime of genocide and a crime against humanity.

"Deportation or forcible transfer of population" means forced displacement of the persons concerned by expulsion or other coercive acts from the area in which they are lawfully present, without grounds permitted under international law," states Article 7 of the Rome Statute: crimes against humanity.

The ICC has already begun collecting evidence of Russia's war crimes and is closely cooperating with Ukrainian authorities to investigate additional human rights abuses and territorial integrity violations.

To hold Russia accountable for all the unlawful actions against Ukraine, the MFA of Ukraine urged the international community to sign a petition titled "Put Putin on trial" on the Avaaz platform in support of its initiative to establish the special international tribunal. Despite requests for its removal from Russian officials. The petition continues to gather signatures from across the globe. Currently, it has the support of more than 1.8 mn people.

Read more:

- How Ukraine is preparing a Tribunal for Putin

- Ukraine launches portal to find children deported to Russia

- 8-months Ukrainian pregnant medic held captive by Russians

- Bucha slowly comes to life after Russian massacre: Dispatch from Ukraine

- NEST initiative gives Ukrainians rebuilding their houses after Russia's invasion a temporary mobile home

- Russia killed Ukrainian POWs in Olenivka to hide signs of torture – Ukrainian intelligence

- Russian war crimes: "denazifying" Ukrainians through deportation, torture, detention, and filtration camps

- Putin officials oversee filtration measures in Ukraine – US at UN