The Syvak family

Ksenia Prokopiuk was born on January 31, 1927, in Tanske village of Uman district. Her father, Hyva Syvak, was a blacksmith. He could shoe a horse or make the necessary agricultural tools, and had his own small smithy. Ksenia’s mother Paraska was taking care of the home farm, since Syvaks had some land. “Wherever you see, there was a farmed field,” Ksenia recalls of that time. Also, the family kept a horse and a cow.

The campaign of dekulakization didn’t touch the Syvak family, unlike many of their fellow villagers who were called “kulaks” by the Bolsheviks and thrown out from their own houses. The cattle and belongings of so-called “kulaks” were taken away. Their houses were dismantled and used as building material—later the kolkhoz constructed the pigsty and barns from it and planted gardens in place of the houses.

Dekulakization was often accompanied by physical violence by Soviet officials and their collaborators, who, having the armed power of the state behind them and feeling impunity, mocked and hurt the people. For example, Maria, the pretty daughter of the Syvaks’ neighbors, was taken away during the dekulakization. Her mother later tried to find out what had happened to her child and whether she had survived at all, but the woman never found out.

When the collectivization started, Ksenia’s parents refused to join the kolkhoz willingly. However, later they still were forced to hand over their land, cattle and smithing tools and to become the members of the collective farm. Due to the mismanagement in the collective farm, the collected horses soon began dying, and the land had to be cultivated with the cows.

People weren’t paid in the collective farm. A small income was nominally accrued to compensate for the days worked for the kolkhoz, but in fact all this money was later deducted as fines, taxes, and other payments, so the net was often zero.

“And what was the workers' payment in the kolkhoz? You bring your cow for mating, and they charge you for it. Maybe, if there was still little money that would be due to you, your small children let your cow get into a kolkhoz

field, someone saw it—it will be noted and you will be charged. In the end, no one had ever had a penny at all,” Ksenia Prokopiuk says.

“And they took everything away from everyone”

In 1932, when Ksenia was only five years old, in her village Tanske, as well as throughout Ukraine, official food searches started in accordance with the instructions of the higher authorities of the USSR. They had only one aim, which was to take away all the food products from Ukrainians and doom them to starvation. This robbery was done by groups of Soviet officials and "aktivisty" (collaborators from local rural population and sent from cities). It is also noteworthy that none of the residents of Tanske who joined these groups died of starvation. “They did not starve… These aktivisty who were close to the [Communist] Party. I know there was the head of the village council... and his whole family survived. There were about ten of them, and they all survived,” the witness recalls. The searches and confiscation of all food created the conditions for destruction of the Ukrainian nation. Also, the genocide became possible through such mechanisms as “black boards,” the “Five Ears of Grain Law,” the prohibition to leave the Ukrainian SSR, the restrictive internal passport system, and the so-called "grain procurement campaign."

A cousin of Ksenia’s father also joined the communist "activists." She compares their experiences: “This one became an 'activist,' and that one was a worker. This one lived in easy street, and that one worked for living.” As a result, the relatives did not talk to each other for the rest of their lives. In this way, the communist regime destroyed the family connections by setting one person against the other.

In order to hide at least some food from the “pillaging brigade,” the Syvaks used some “tricks.” For example, they spread some rye onto the stove shelf used for sleeping, put their children over it and told them to be still so the rye would not rustle. During the search, the parents lied to the aktivisty explaining the children were very ill. The brigade believed them, since many children in the village were already swollen from starvation. In this way, the family managed to survive for some time. Also, Ksenia’s parents were able to save some food by hiding it in a hole in the stove, which they covered up by wooden boards and white clay.

The most devoted aktivisty stooped as low as to even search the manure pits. “These aktivisty searched where the manure was and near the manure. I saw that there was a mess made, meaning they searched there. They searched everywhere.” Moreover, there were those who checked for hidden food even in the toilets. “There were also some ‘five-hundreders,’ they checked the toilets,” Ksenia recalls.

Sometimes aktivisty took advantage of the fact that adults worked on the collective farm all day and conducted searches when only children were home and unable to resist. After the brigade searched the Syvaks' house several times in this way, the parents started locking the children in the house when they were not home.

Also, Ksenia’s parents were afraid that their cow, whose milk saved the family from dying, might be stolen. That is why they kept the animal tied to a table in the house, and took turns watching it at night. Such fear was justified, as thieves not only stole the neighboring Chyzhenko family cow and slaughtered it in the woods, but also attacked the housewife and locked her up. Fortunately, the woman survived, but her three children later died of starvation.

The house was also locked against beggars entering the house, but as there was nothing to steal—Ksenia's father Hyva Syvak had already exchanged all the more or less valuable clothes, shoes and jewelry for grain in the city.

Surrogates

Surrogates, substitutes for normal food, became almost the only salvation for starving people. Among them, Ksenia Prokopiuk remembered the nettles, goosefeet, pilewort and other plants.

Once Ksenia’s father found some yellow fodder beets and her mother cooked them.

Ksenia's grandmother Maryna worked at a pig farm and when she could she would steal some oilcake (dross from sunflower oil production, used as animal fodder) in a secret pocket of her skirt for them. She divided the food among her grandchildren equally, everyone receiving a handful. Later in 1933 she died of starvation herself.

Often the famine pushed people to desperate actions. Ksenia and her younger sister Hanna witnessed how their fellow villagers attacked an unattended horse walking down the street and cut it into pieces to eat. “Even the intestines were taken away,” the woman shared her memories.

A case of cannibalism happened in the village, too. The body of Ksenia’s friend Natalka was found cooked in the house of her neighbors. “We were told, if you walk on the street and someone offers you some necklace or something, don’t go with them. Don’t go into their house. Walk straight home.” This is how the parents tried to protect their children from the worst.

“No one cried, no one was sorry for anyone, they just died and that was all.”

One of Ksenia’s most horrible memories of that time is the death of her youngest brother Mykola, who was just an infant. Despite the family feeding the boy with cow’s milk, they couldn't manage to save him, and the child died in front of everyone.

“My mom gave him to me. I held him while they made the bed for him. He started hiccuping and my mother said, ‘Don’t shake him.’ I replied, ‘I'm not shaking him, he has hiccups.’ Then they laid him in bed where he hiccuped one more time and died.”

Her parents buried the child on their own, but they didn’t mark the grave.

Later Ksenia Prokopiuk many times witnessed the deaths of her relatives and neighbors. For example, once she came to the house of her neighbors the Muzykas to bring them some milk. Their son Dmytro was swollen from starvation, and the parents asked the Syvaks for help. However, the boy couldn’t drink it. Ksenia recalls, “I brought the milk, and he was dressed up laid out dead on the table. I said, ‘I brought the milk for you, why are you lying here?’ and they all looked at me strangely...” Three more people died in this family afterwards.

Ksenia’s uncle Andrii Koval also became a victim of the Holodomor. In order to properly bury him, her father Hyva made a coffin. The body remained in his house for three more days since the two men who collected the dead and drove them by horse-pulled cart to the cemetery were too weak to lift the coffin.

Mostly the traditional funeral rites were set aside: “They buried the dead without coffins. They dug big pits in the cemetery for those who died and piled the bodies in them. They piled them up until the pit was full.”

In 1932-1933 many inhabitants of Tanske died of starvation. Yet, according to the official data, only 123 people were killed by famine in the village. The real number is still unknown.

Mykola and Maryna Syvak, Todos, Lehera, Pavlo and Dmytro Muzyka, Hnat Petro and Maria Chyzhenko, Halyna and Polina Petrenko, Ivan and Andrii Koval, Fedir and Volodymyr Franko, Andrii, Kateryna, Fedir and Samiilo Burlachenko—all these people became the victims of the genocide. Along with them, Holodomor took the lives of many other relatives and neighbors of Ksenia Prokopiuk, but she doesn’t remember their names.

“Maidan”

For the children whose parents died of starvation, the kolkhoz organized a kindergarten named “maidan,” where the orphans were given some food. For some time Ksenia and her younger sister had also been eating there, but it didn’t last long. The management was informed that the family had a cow and so the girls were no longer fed. “We had a cow, it means, they won’t give us any food,” Ksenia Prokopiuk says.

Incidentally, the wife of Ksenia’s godfather worked at the “maidan.” She distributed bread for the kids—everyone received 100 grams (3.5 ounces). Once she wanted to give Ksenia a little more than “normal”, and poured her a handful of crumbs. However, the girl was too small to understand this idea and was offended. “When I saw that I got crumbs, while everyone got whole pieces, I threw the crumbs on the ground! She was shocked: ‘What's that? Did you already eat?’ Right away, all other children got on their hands and knees to snatch the crumbs like chickens and I didn’t get anything.”

One of Ksenia's family's neighbors also worked there. Although she was a Komsomol communist youth organization member and an aktivist, seeing that Ksenia was very weakened, the woman also tried to help her. “She wanted the best for me—to give me more crumbs of that bread. My father had asked her: ‘Help her as much as you can, she barely eats, maybe you could help her.’” There were some communist "activists" who showed some humanity.

History of the church

At first, the Soviets turned the village of Tanske's ancient wooden Church of St. Dmytro into a propaganda and community center (so-called “house of culture”), and then they completely dismantled in 1940. Earlier, during the Holodomor, the building was set on fire (“People said the fire was set by Communist Party members,” recalls Ksenia), but the inhabitants of the village managed to extinguish it.

Communist aktivisty

treated the local priest cruelly. He was locked until he died in the basement of the village council, which was located in the house of a "dekulakized" family. “No one could find him there, they covered him up with garbage, and that's it,” Ksenia recalls.

During the German occupation, the priest’s son, who was also a priest, returned to Tanske and conducted religious services in the premises converted back into a church. When the communists returned to Tanske, a large tax was imposed on him, and he had to leave the village forever.

Famine of 1946-1947. Trip to Belarus.

The next life challenge for Ksenia was the mass terror-famine of 1946-1947 when she was already nineteen years old. At the time, the decree of August 7, 1932, known as the "Five Ears of Grain Law," was still in force. It forbade anyone from picking up even small remnants of the harvest from the collective farm fields. That's why several Tanske residents were imprisoned. “One woman, she took seven beets left in the field after harvesting, and they gave her a seven-year prison term. And the neighbor, who took three or four hundred grams (10-15 ounces) of barley in her pocket, got four years.”

A trip to the neighboring republic of Belarus in the spring of 1947 saved Ksenia from starvation. Together with her friend and several other villagers, the girl traveled by train where she exchanged home-made clothes and embroidered towels for food for several weeks. The starving villagers from Ukraine begged locals for food and those who could often shared what they had. “We would walk and walk, and the locals would give us some liquid to eat in a big clay bowl. It was water, but with a little lard, and somewhere in there is a pea. They also cooked big potatoes and you could take one and eat it. And, if you exchanged some of your things, you could even get a piece of bread. But they wouldn't give it to you without a trade. Then we would walk more and ask other local people to trade our belongings for food to let us eat even a small bit in exchange.” Ksenia never found a prosperous life in Belarus, but there was no famine there either.

On the border between Ukraine and Belarus, there were many thieves robbing those who went in search of food. One of them used a razor to cut Ksenia's bag that held things for exchanging, but she managed to escape and even to save her belongings. She returned to her native village with 24 kilograms (52 lbs.) of rye and barley, which was enough to save her family.

During the mass terror-famine of 1946-1947, the mortality rate was not as high as in the years of the Holodomor genocide. Nevertheless, several inhabitants of Tanske did not survive this time. Among them was a girl named Dunia, an orphan, who was found in the field by herself during Holodomor in 1933. She was brought up in the kolkhoz orphanage and received the surname Vesela (“Cheerful”). She was the youngest pupil at the orphanage so when all the children graduated, the girl was left alone. She had no one to take care of her and in 1947 she died.

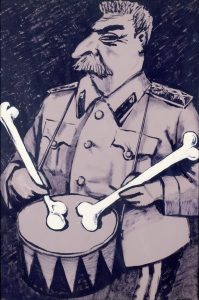

Propaganda

The propaganda of the communist regime always promised Ukrainians a happy life and the construction of a “new order.” In contrast, it brought destruction, arrests, famine, and mass death. And although some believed the loud propaganda slogans, most did not accept the Bolshevik “innovations.”

The true attitude of Ukrainians regarding communist propaganda is evidenced by the following eloquent fact: Ksenia’s mother Paraska hung a paper portrait of Lenin near the stove to protect the wall from soot. She hung it horizontally. When the wife of one of the communist "activists" saw this, she warned the woman that she and her family might be punished: “Paraska, what do you think? They will fine you, exile your family, and send your husband to prison.” Then Paraska turned the portrait to face the wall so that only the back of the sheet was visible. In the end, the communists did not succeed in transforming Bolshevism into a new quasi-religion.

The staff of the Holodomor Museum recorded Ksenia Prokopiuk’s story in Svitlovodsk town of Kirovohrad oblast as part of the project “Holodomor: Mosaics of History. Unknown Pages,” supported by the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.

Further reading:

- Half our village died of starvation, mostly the elderly | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- My neighbor buried her three children | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- Every day two or three people died in our village | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- My village once saw twelve people die of hunger in one day | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- My family survived Holodomor by eating waste left from sugar production | Voices of witnesses

- Surviving in the “collective farm paradise”: voices of living Holodomor witnesses

- How my father saved his co-villagers from starvation during the Holodomor

- My neighbors escaped starvation by eating grain stored by field mice | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- “Let me take the wife too, when I reach the cemetery she will be dead.” Stories of Holodomor survivors

- Stalin’s management of Red Army proves Holodomor a Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

- Holodomor in Kharkiv through the lens of Austrian engineer: photo gallery

- Holodomor: Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts