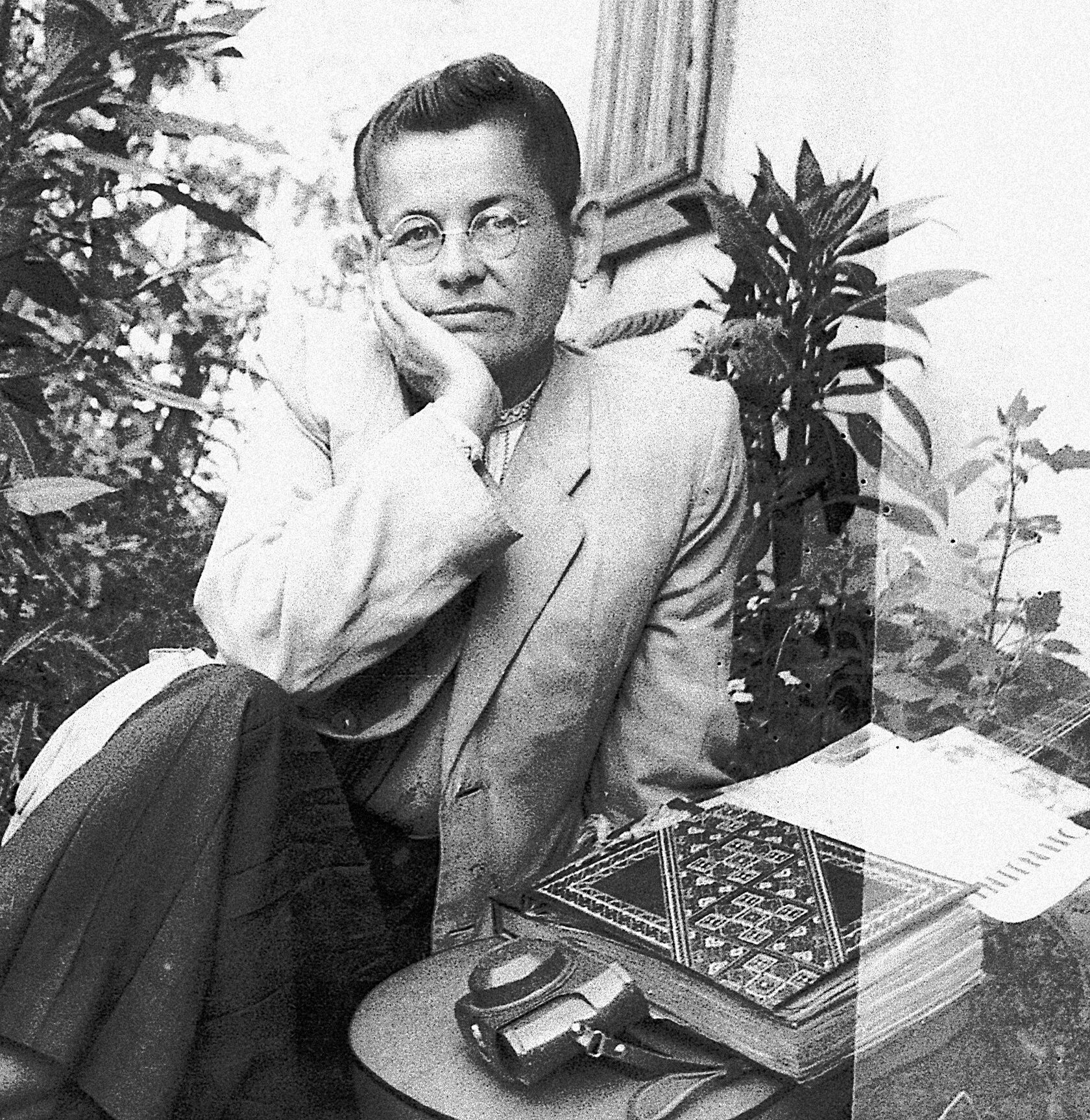

She is in a way a Ukrainian Vivian Maier — an American self-taught photographer who, unknown during her life, took more than 150,000 photographs documenting life in cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

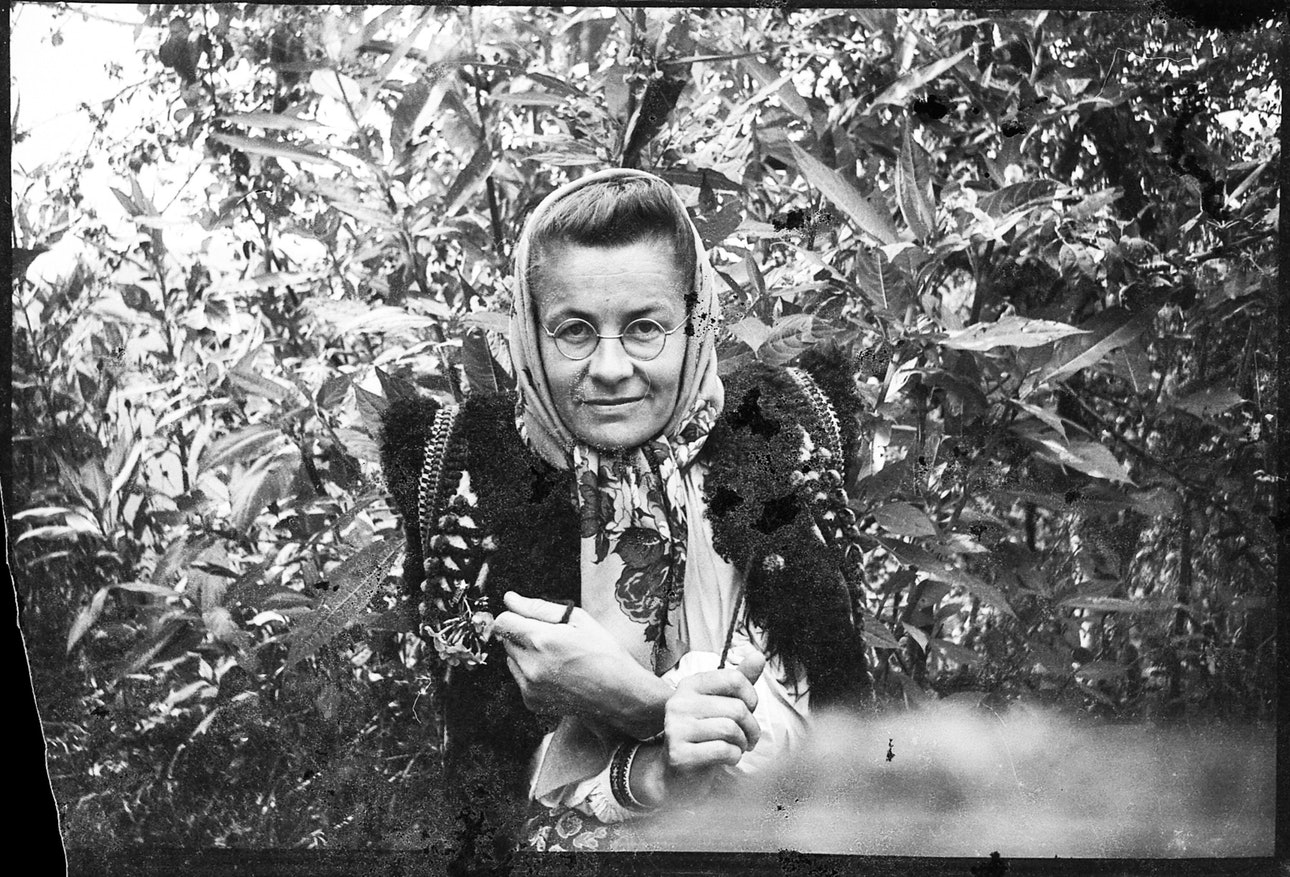

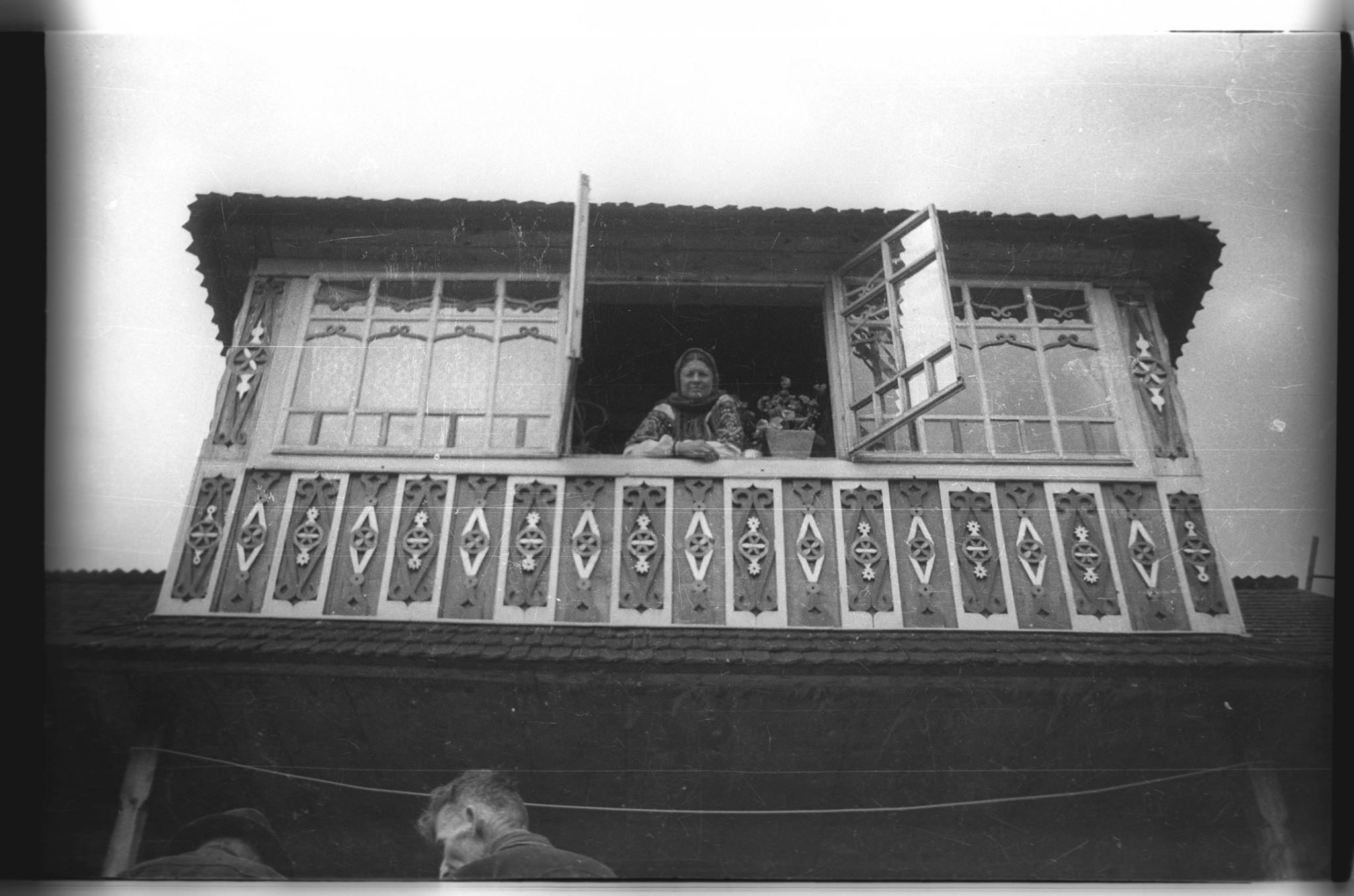

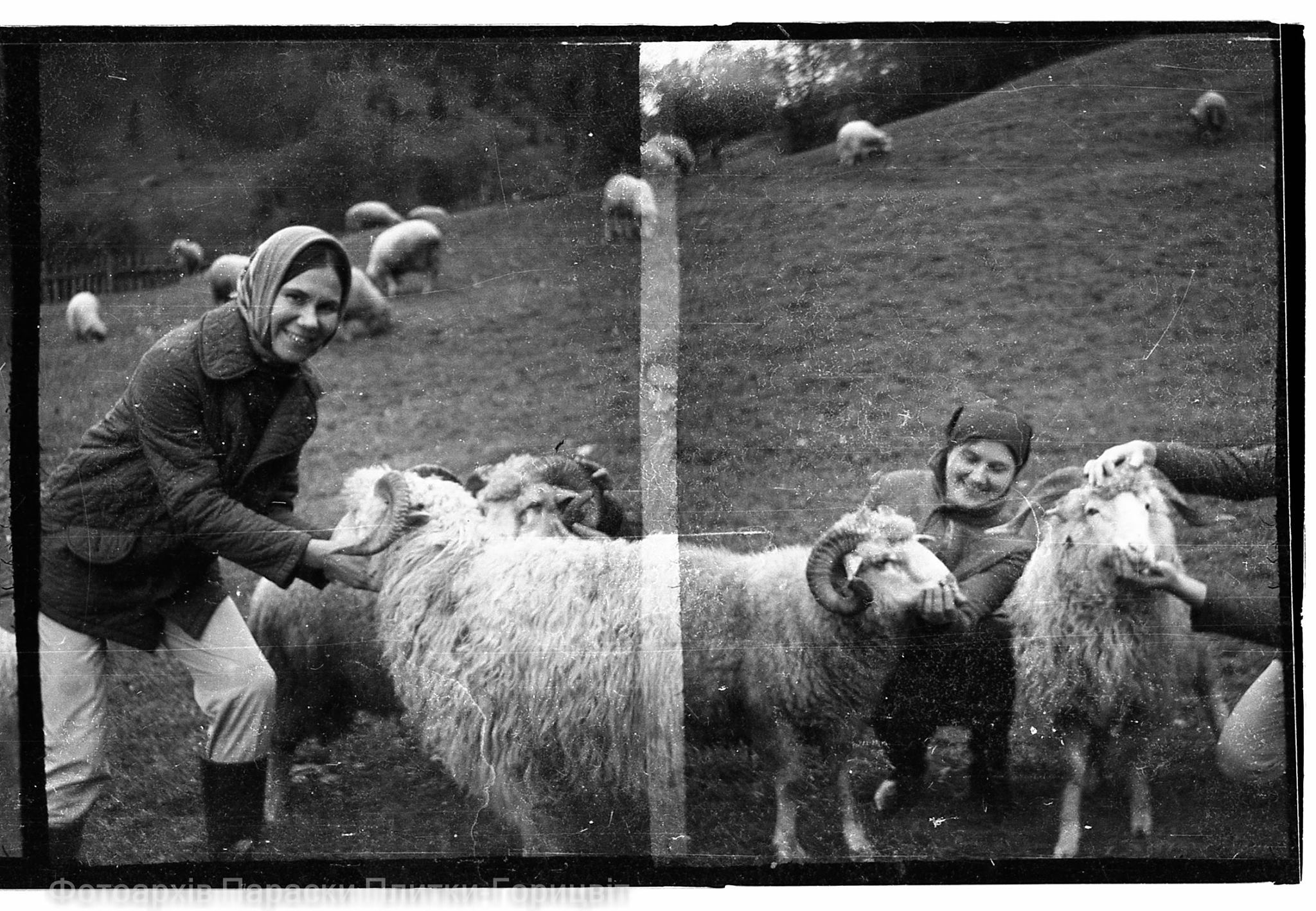

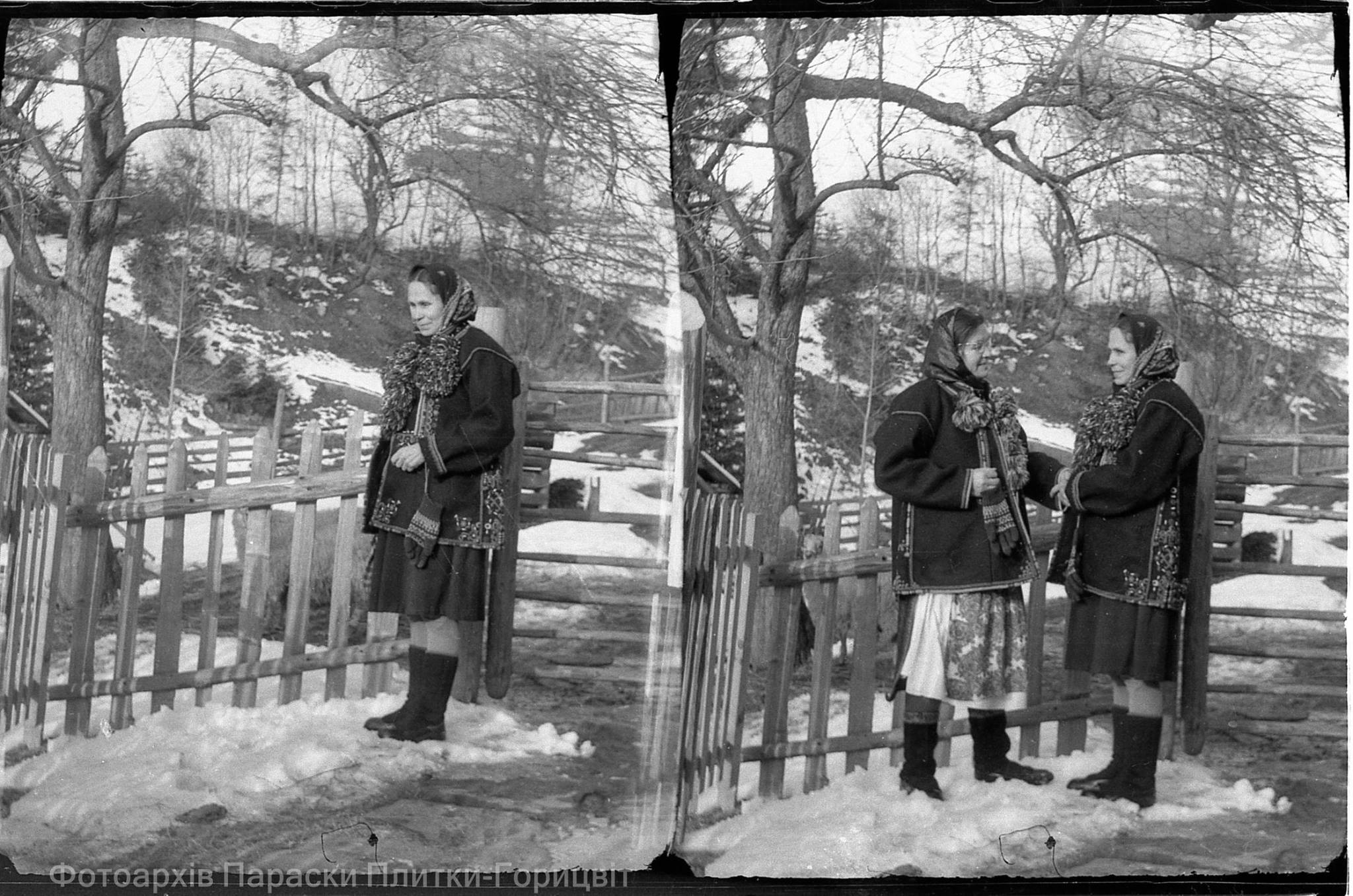

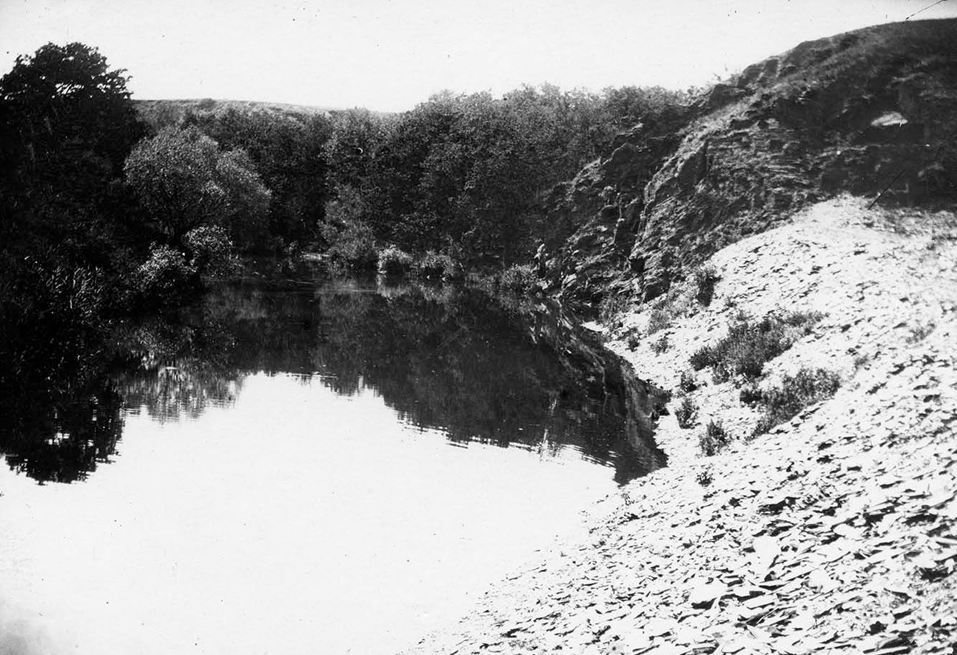

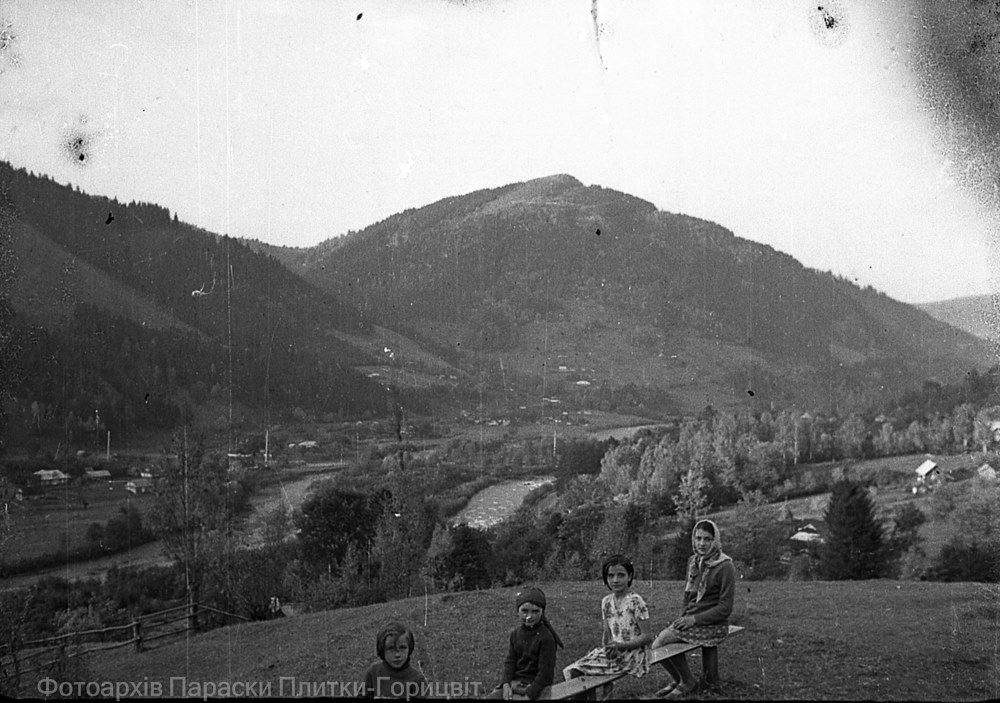

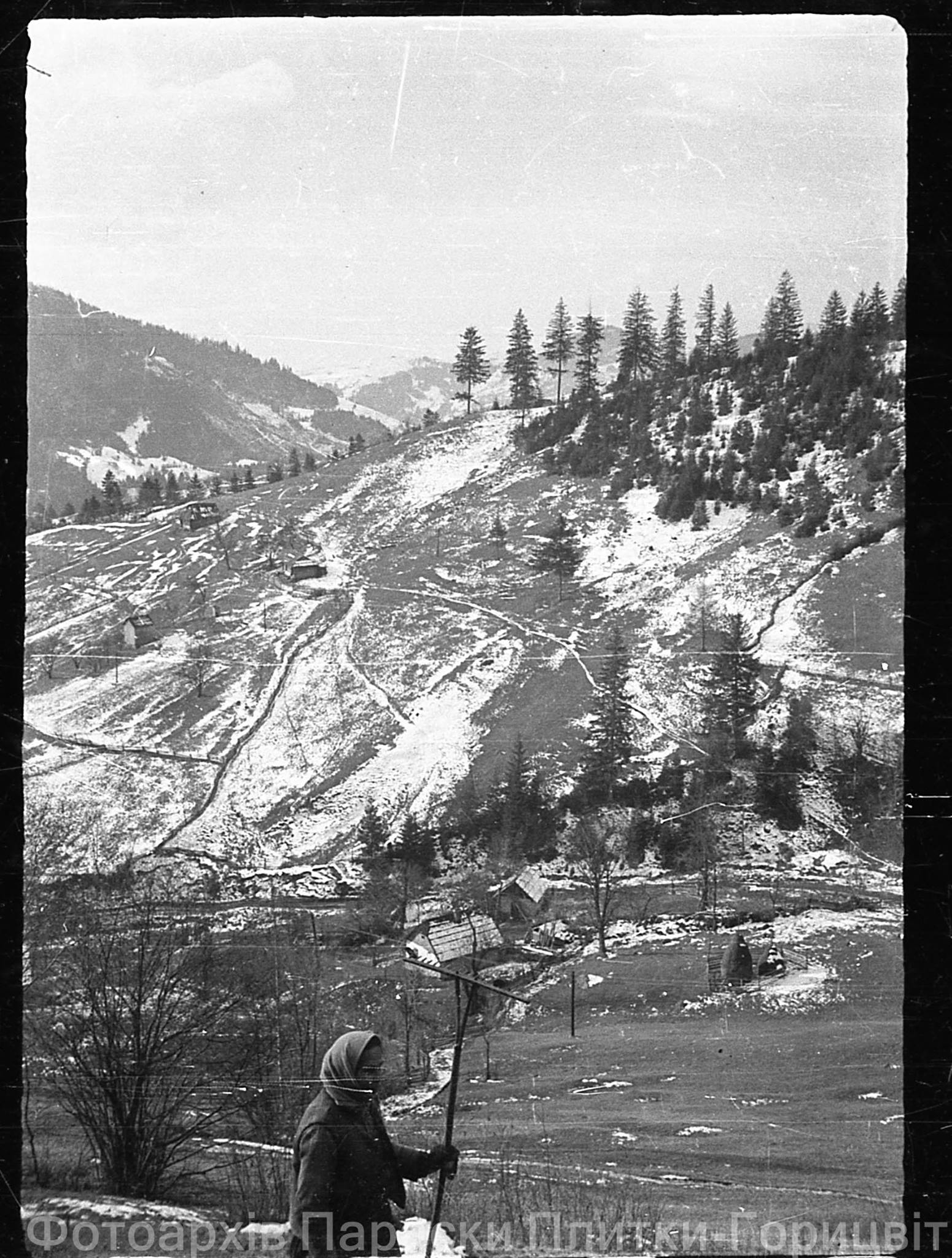

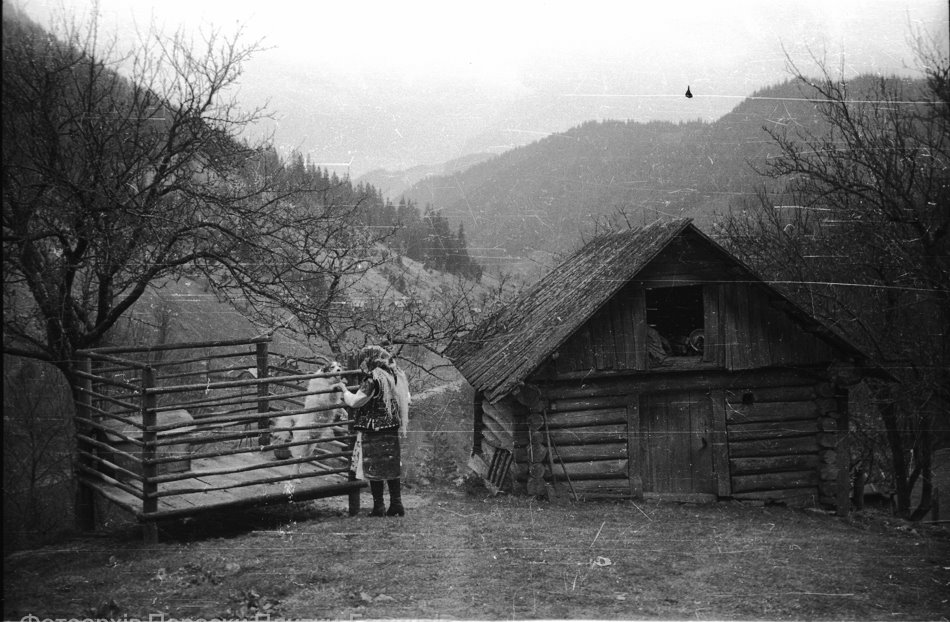

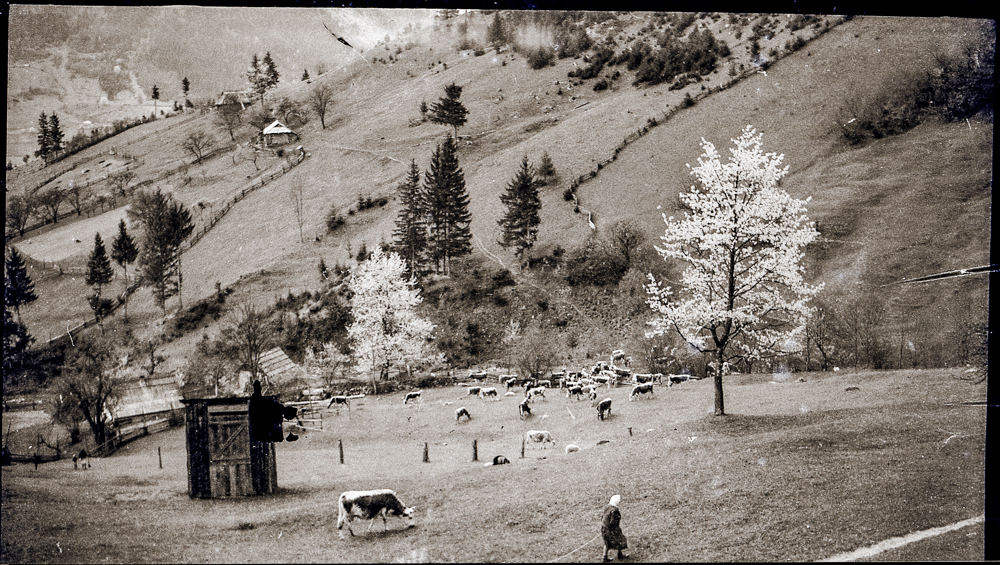

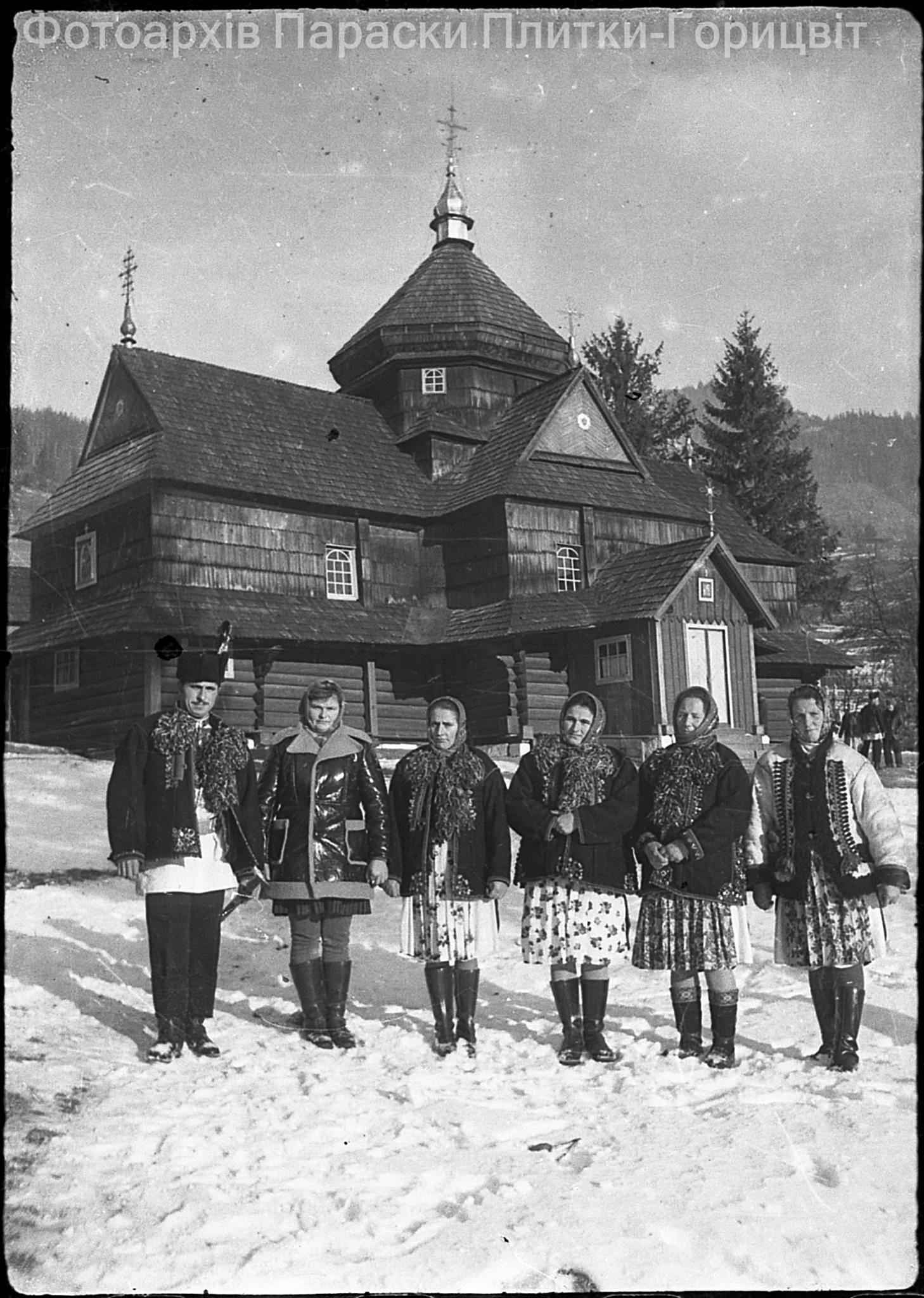

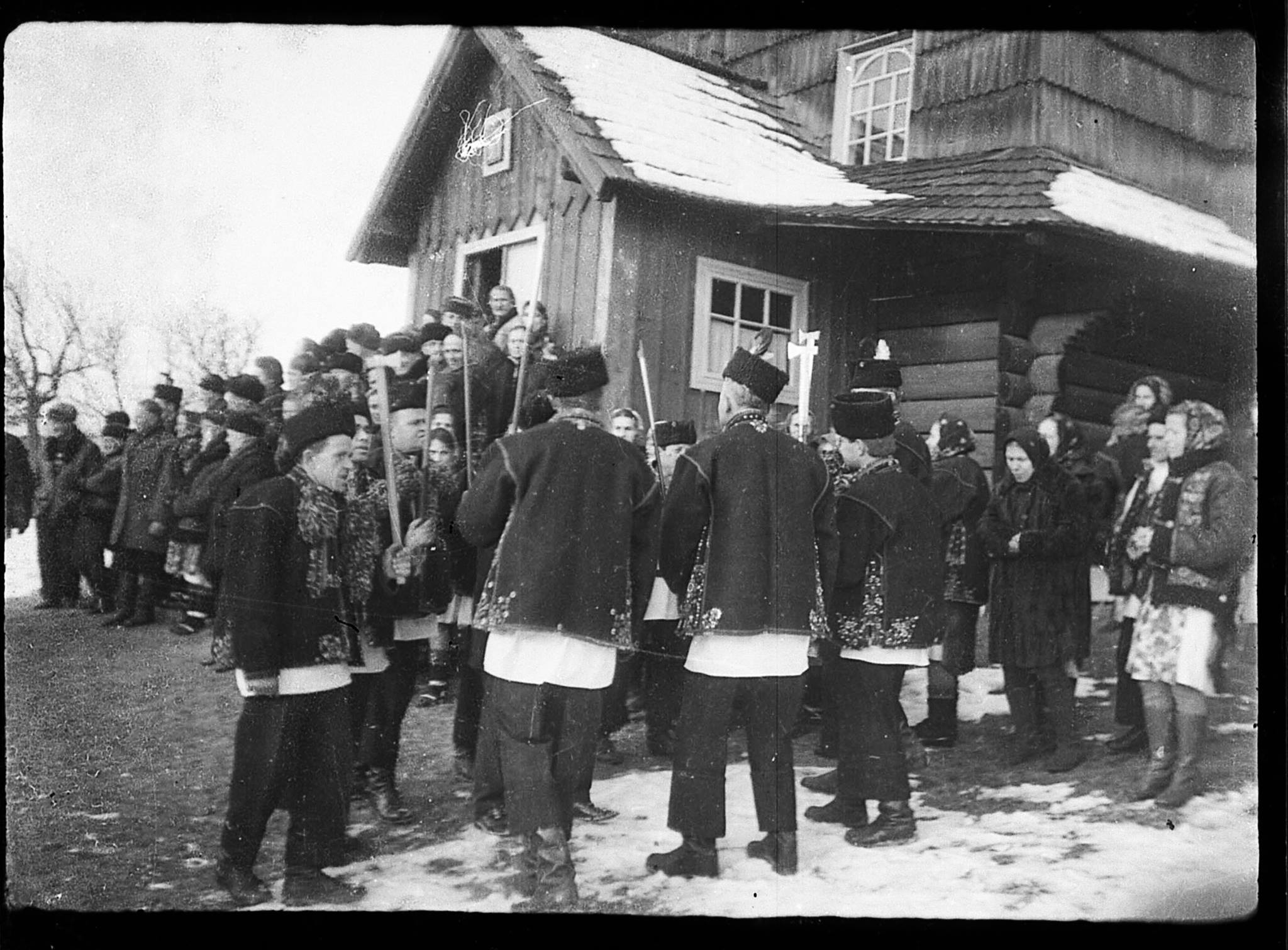

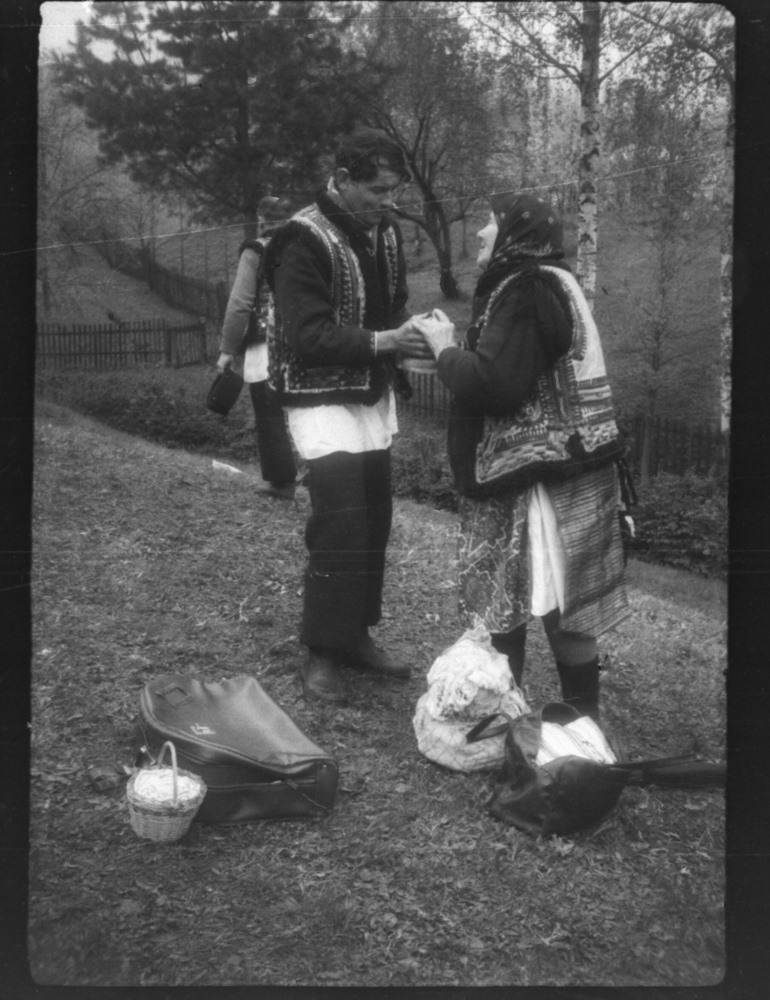

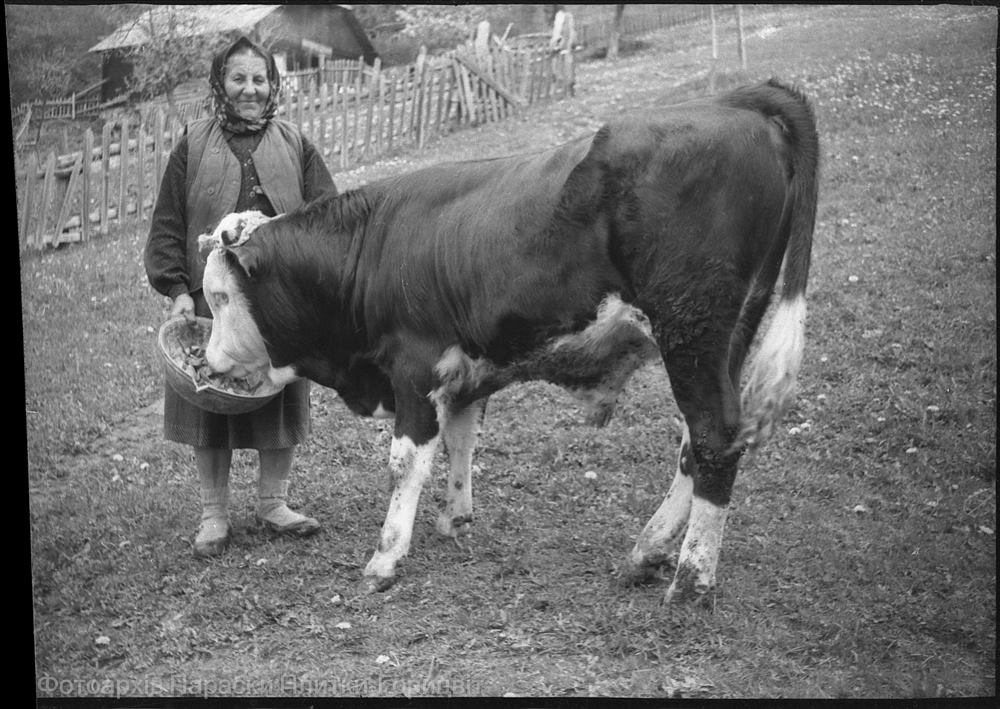

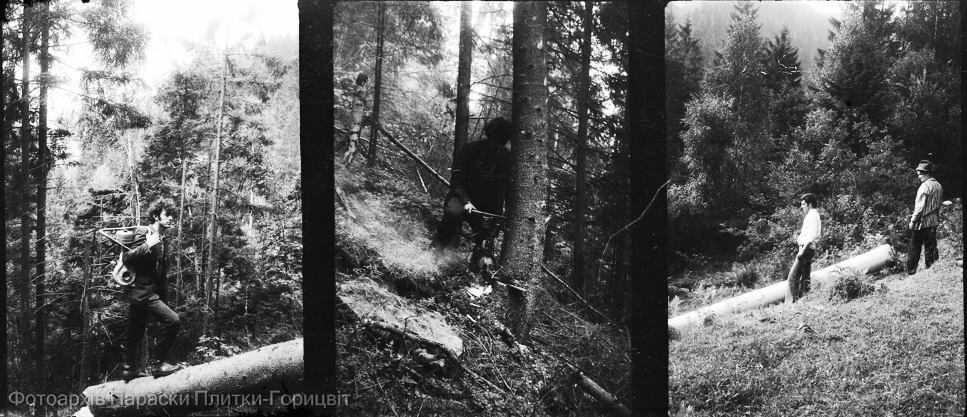

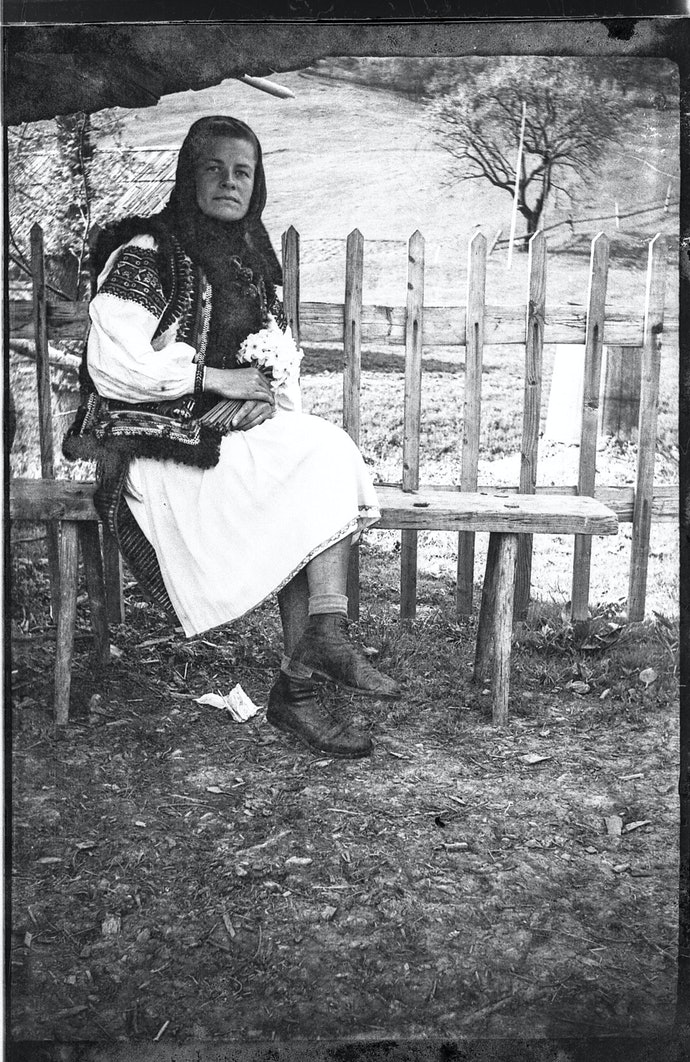

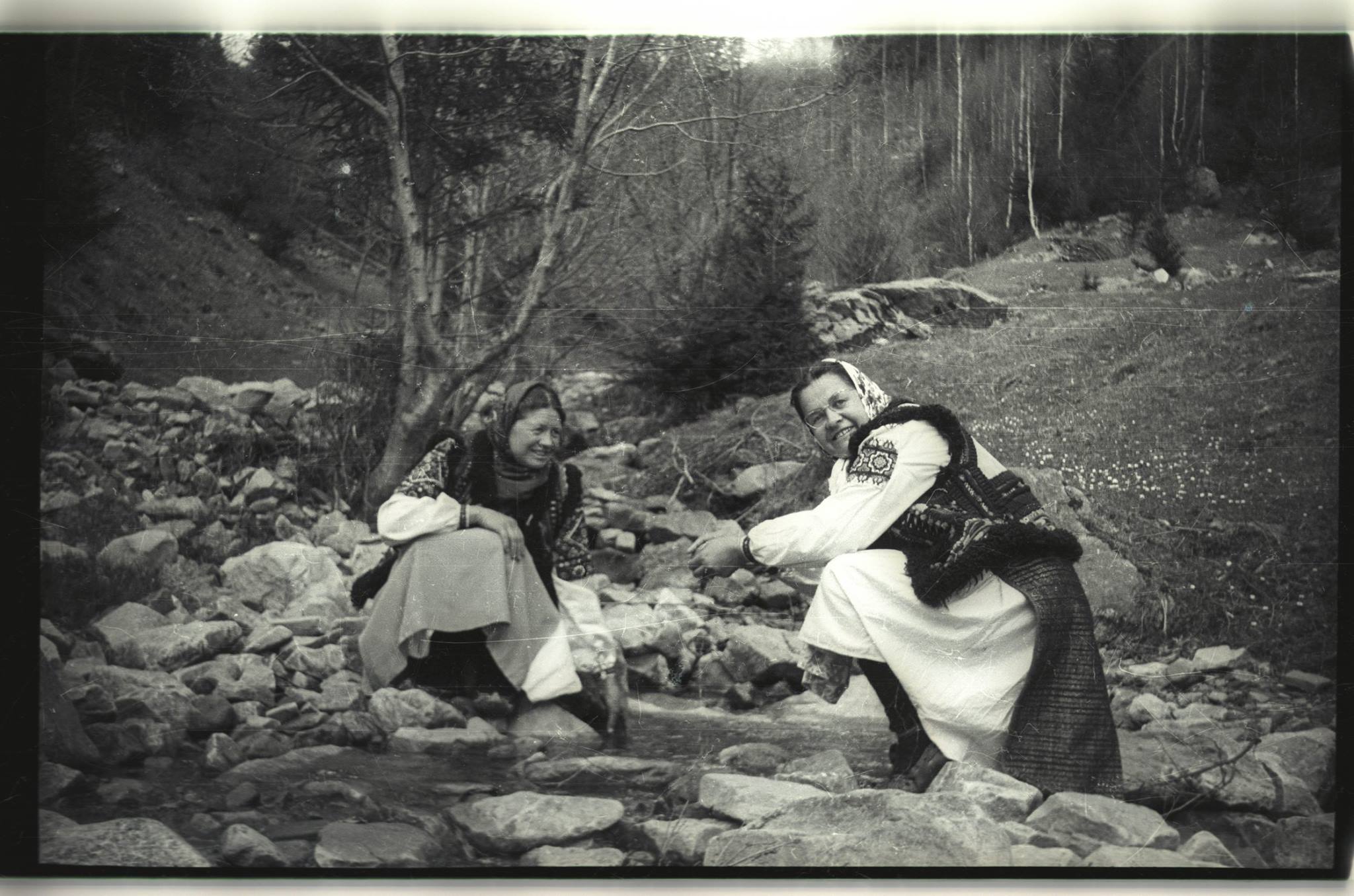

Like all Hutsul mountaineers, Paraska had an indomitable spirit and a creative talent which she put to good use, mastering the art of photography on her own, recording church holidays, folk rituals and traditions, Hutsul life and, of course, the Carpathian landscapes.

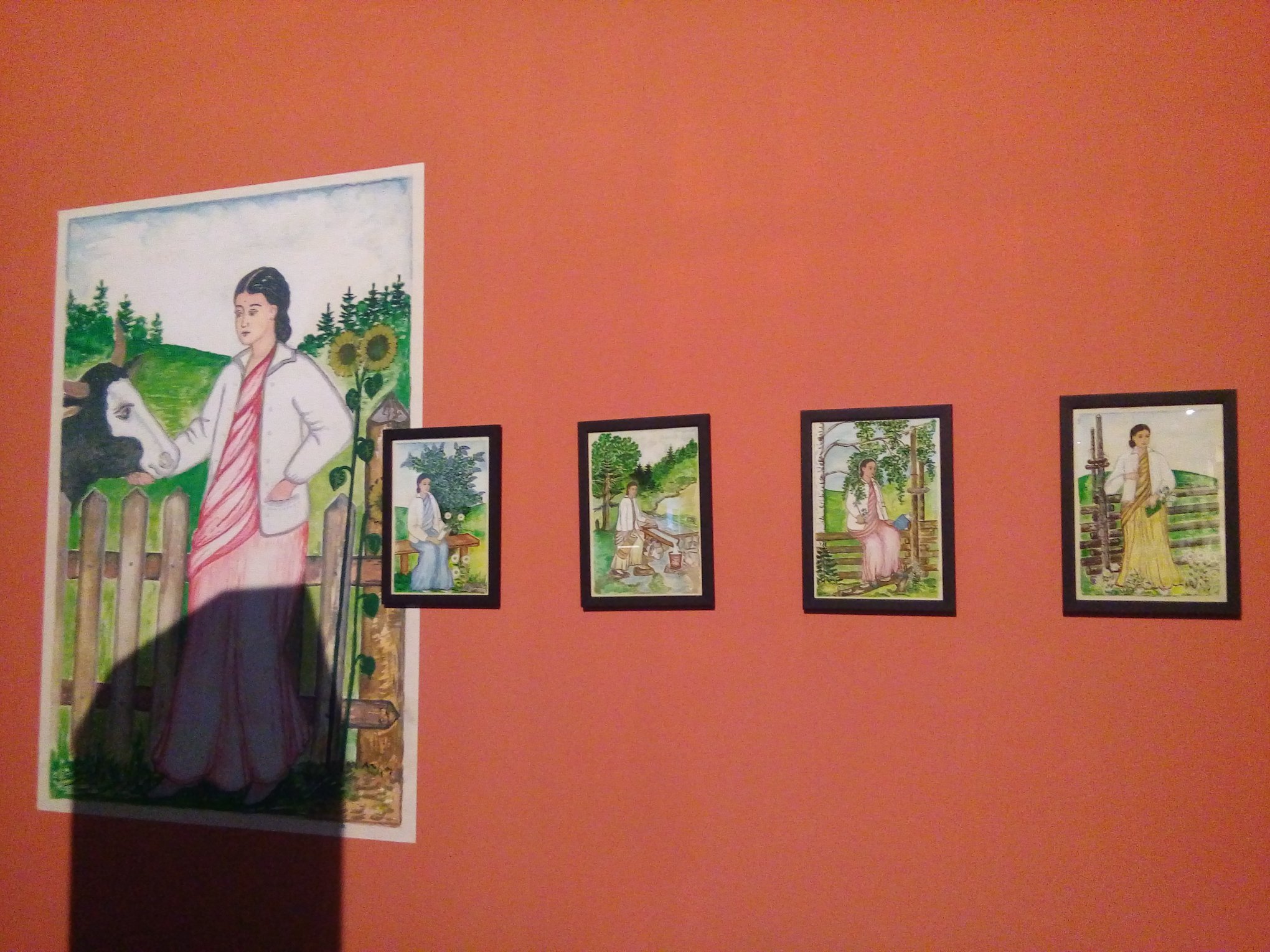

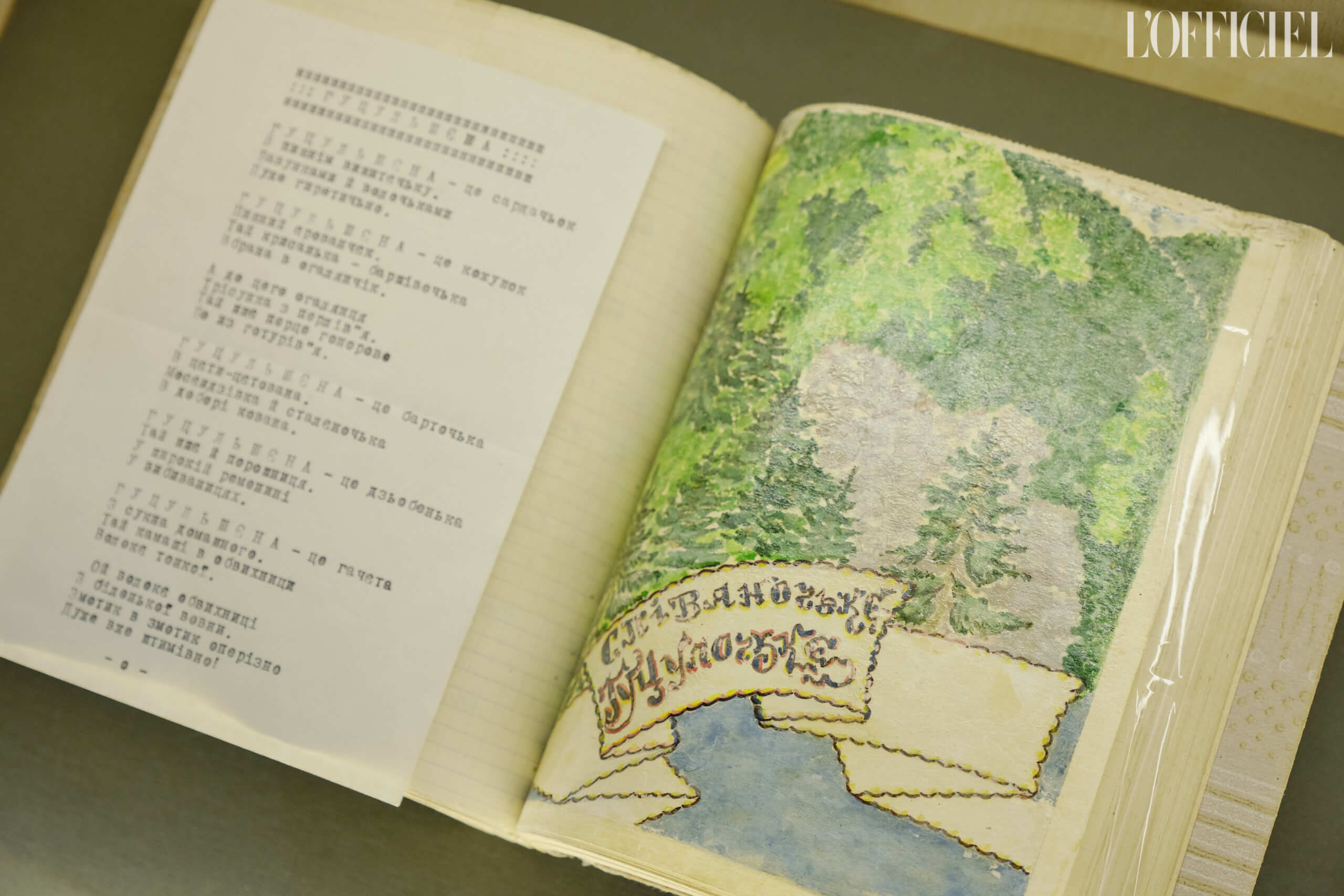

Paraska’s creative output includes more than 4,000 photographs and about 500 books. She wrote many of her manuscripts in the Hutsul dialect, but very few were published during her lifetime. She did not limit herself to photography, but also wrote poetry, created handmade books, explored Indian art and culture, corresponded with soldiers, exiles, dissidents and some friends abroad, and painted portraits, naive art and icons.

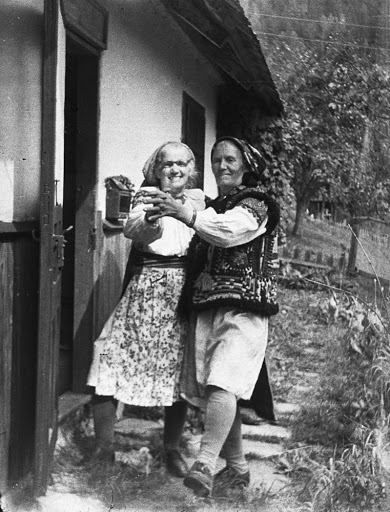

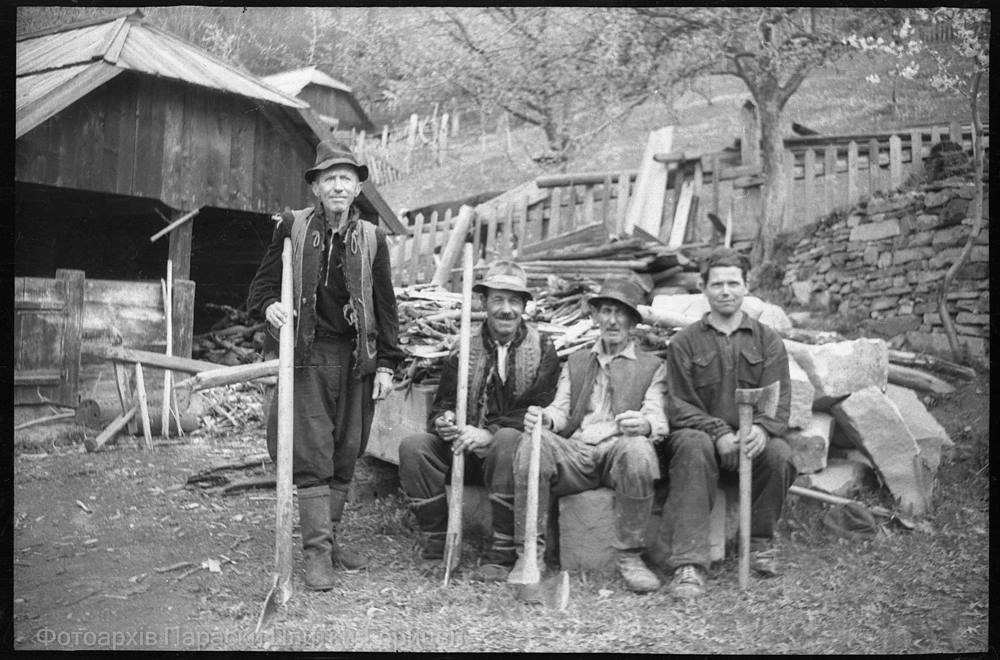

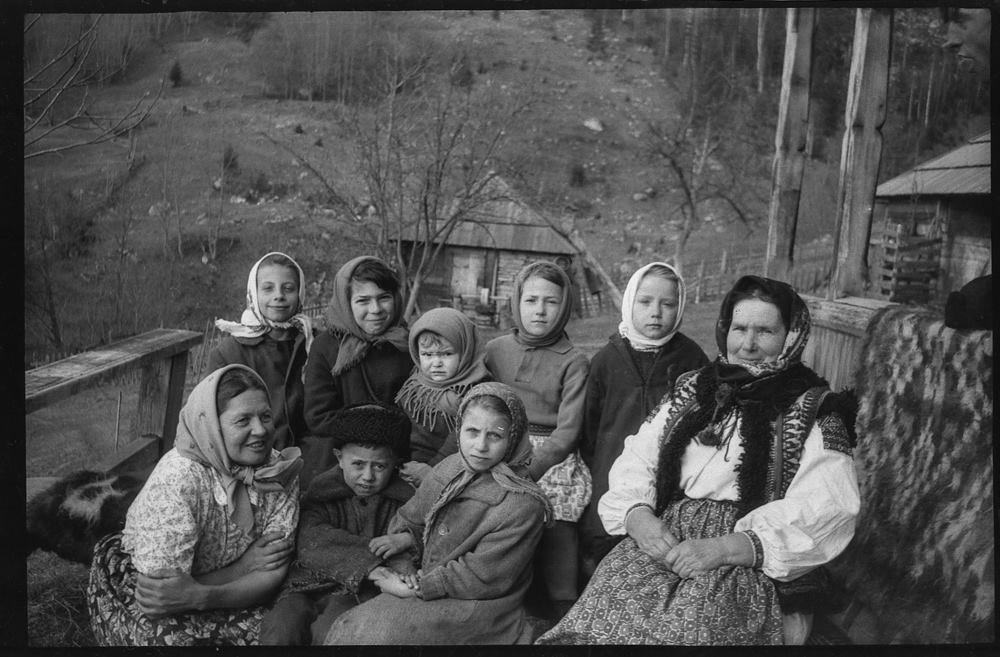

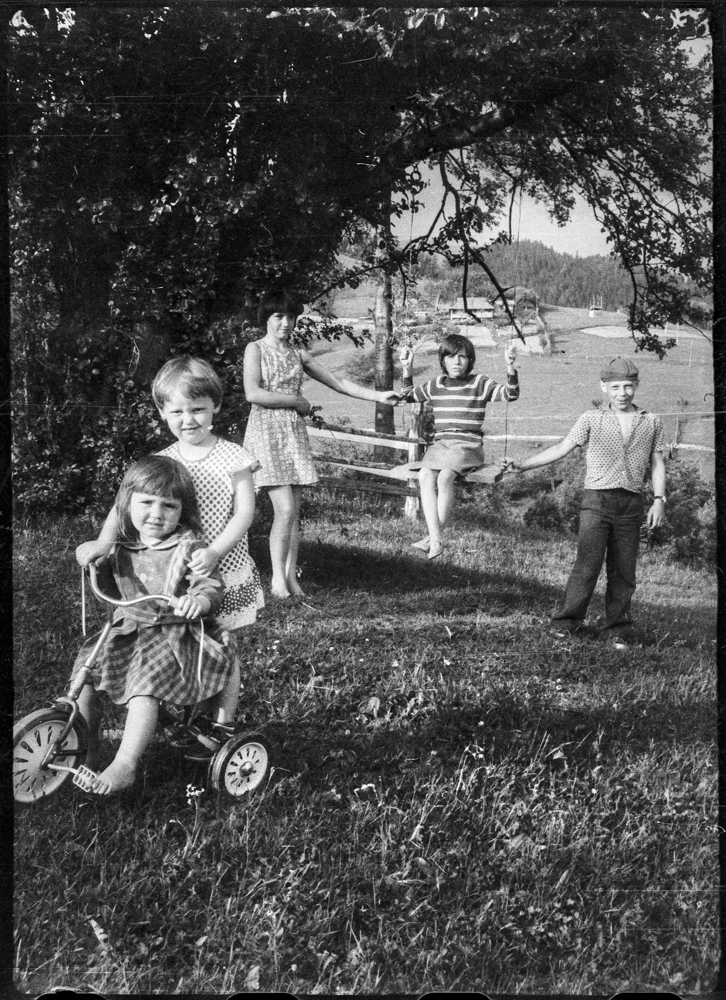

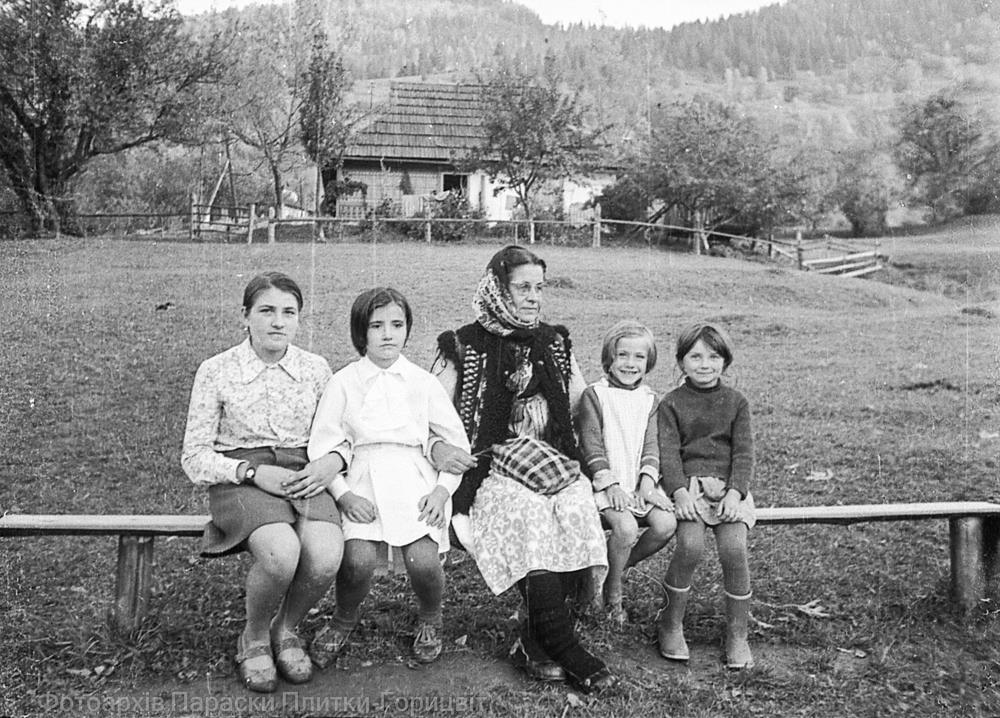

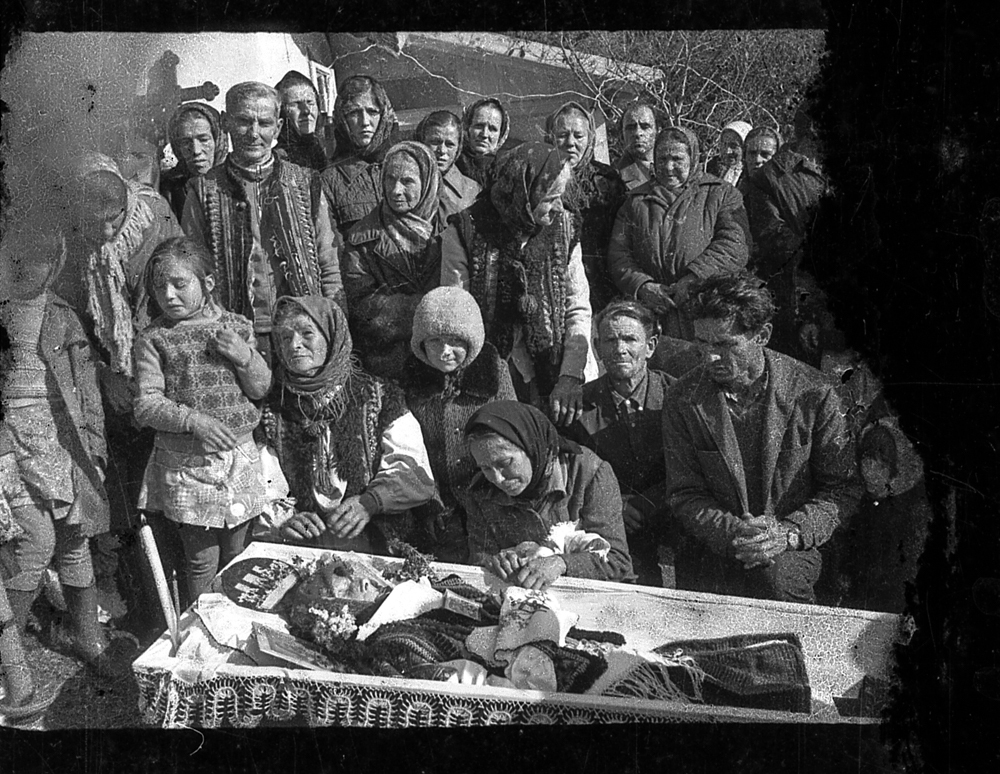

Hutsul life

Early life in the Carpathians

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit was born on March 1, 1927 in the village of Bystrets, Verkhovynsky Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Her father, Stepan Plytka, was a well-educated blacksmith and his wife Hanna, worked as a master weaver and embroiderer. The family soon moved to Kryvorivnia where Paraska completed four grades in primary school, and then was homeschooled by her father who also taught her German. During World War II, she worked as translator at the village administration.

In 1943, she travelled alone to Germany, where she hoped to gain a higher education. Unfortunately, she was forced to work in a factory and as a housekeeper. She returned to Kryvorivnia and joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), where she worked as a liaison courier under the call sign “Lastivka” (Swallow).

Hutsul life (cont'd)

Exile in Siberia

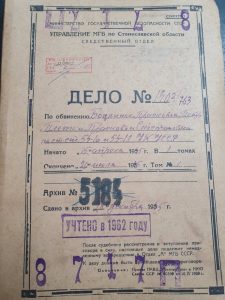

On March 10, 1945, 18-year-old Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit was arrested for her activities in the OUN / UPA movements.

After four months in prison, the NKVD military tribunal sentenced her to ten years in prison, deprivation of civil rights for five years and confiscation of all property. Paraska and hundreds of women from Western Ukraine were herded onto freight trains and sent to Siberia.

“Instead of warm clothes, they gave us oversized blood-stained overcoats that they’d taken from the executed prisoners,” she remembers.

It was so cold in the Kolyma penal colony that Paraska fell ill and her feet were frostbitten. She stayed in the Ural prison hospital, where she was miraculously saved from amputation by a Georgian doctor. For almost five years, Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit had to use crutches. In 1947, she was transferred to a special penal colony in Kazakhstan.

Ten years later in 1954, at the age of 27, Paraska finally returned home to her beloved Kryvorivnia.

A life dedicated to God, photography & creativity

When Paraska Plytka Horytsvit arrived in Kryvorivnia, she was greeted with hostility and suspicion by her fellow villagers, who kept their relationship with her at a distance, all of this due to fear of brutal reactions of the Soviet authorities.

Carpathian landscapes

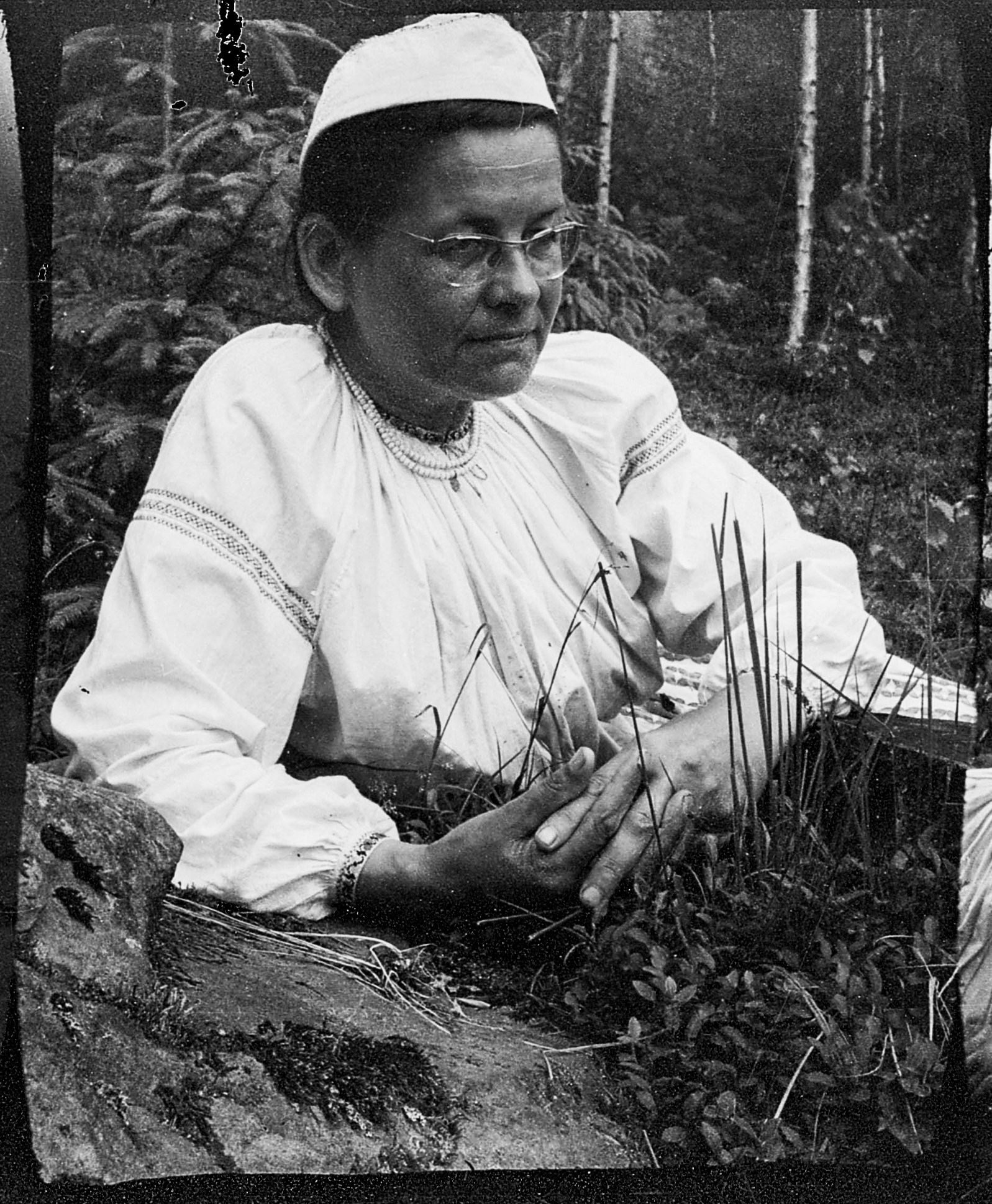

Paraska never spoke of her time in exile, but joined in village activities and gradually regained the confidence of the villagers. She lived alone, dedicating much of her time to prayer, and began painting, writing and recording ethnographic observations. She was hired as an artist in a local lumber company, and used her first salary to buy a Smena camera, and her second salary - a photo enlarger.

Religious celebrations in Kryvorivnia

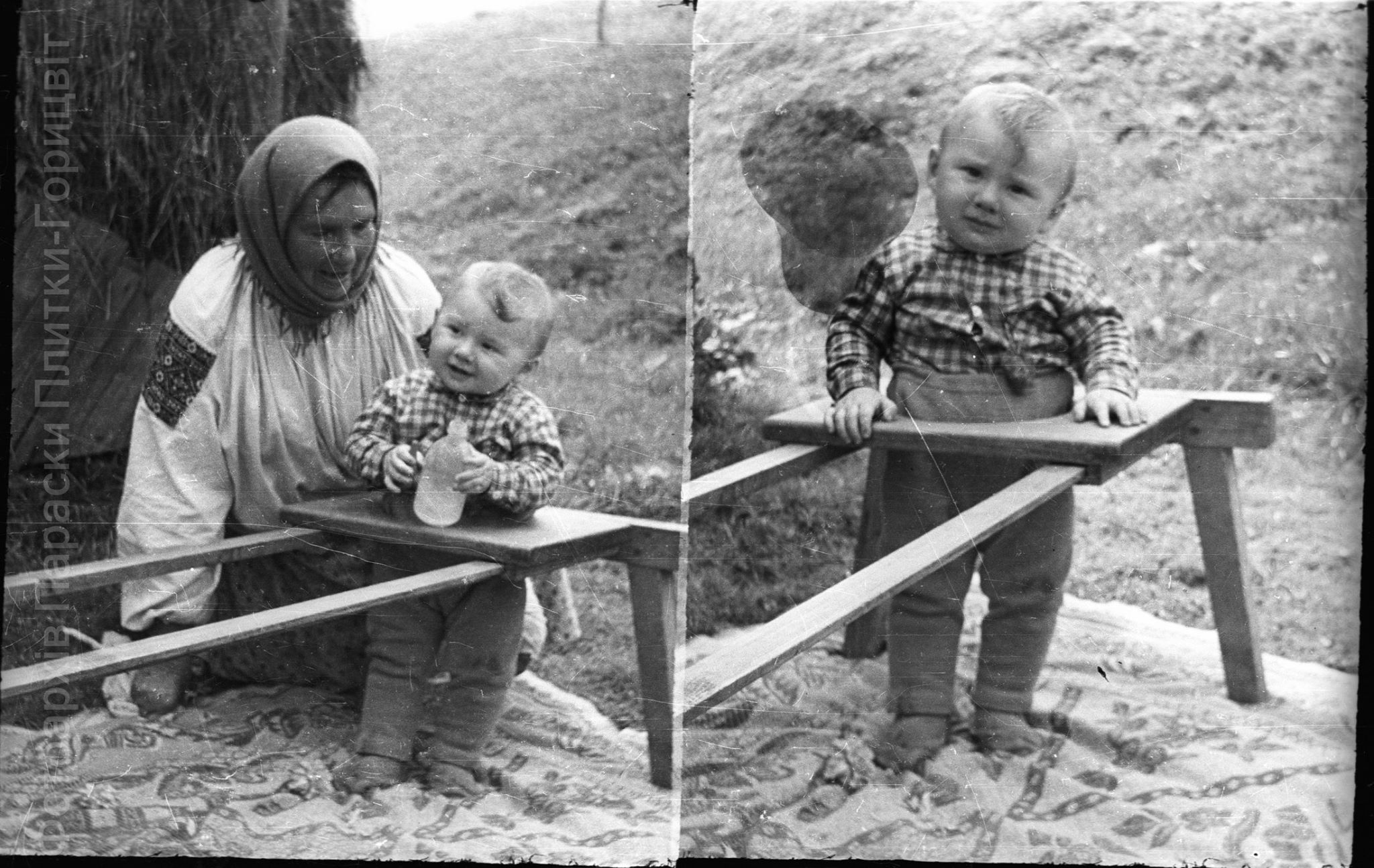

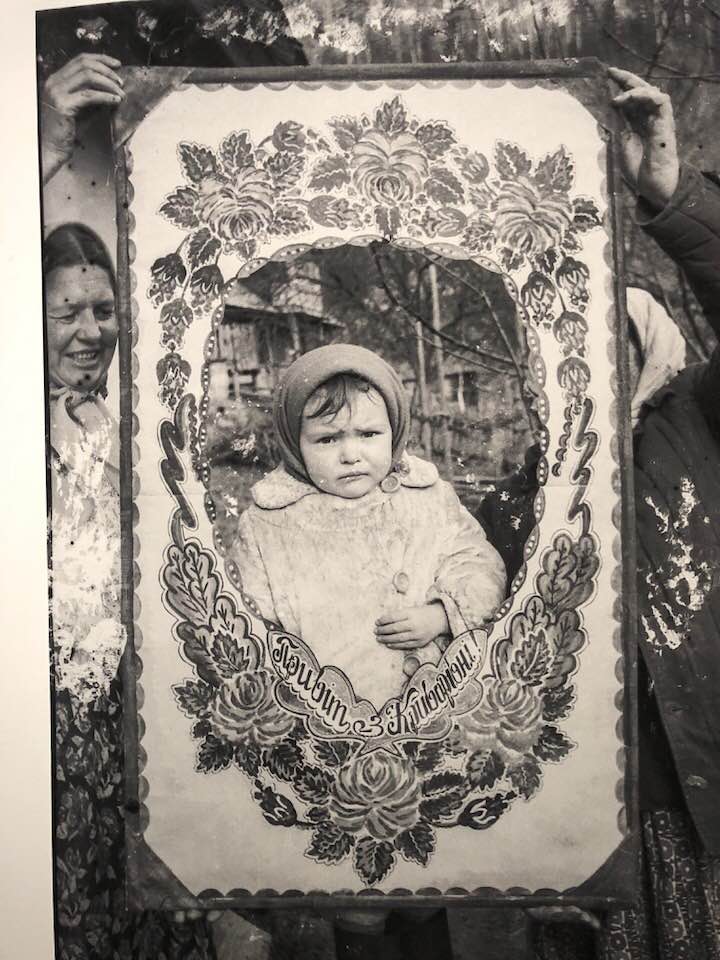

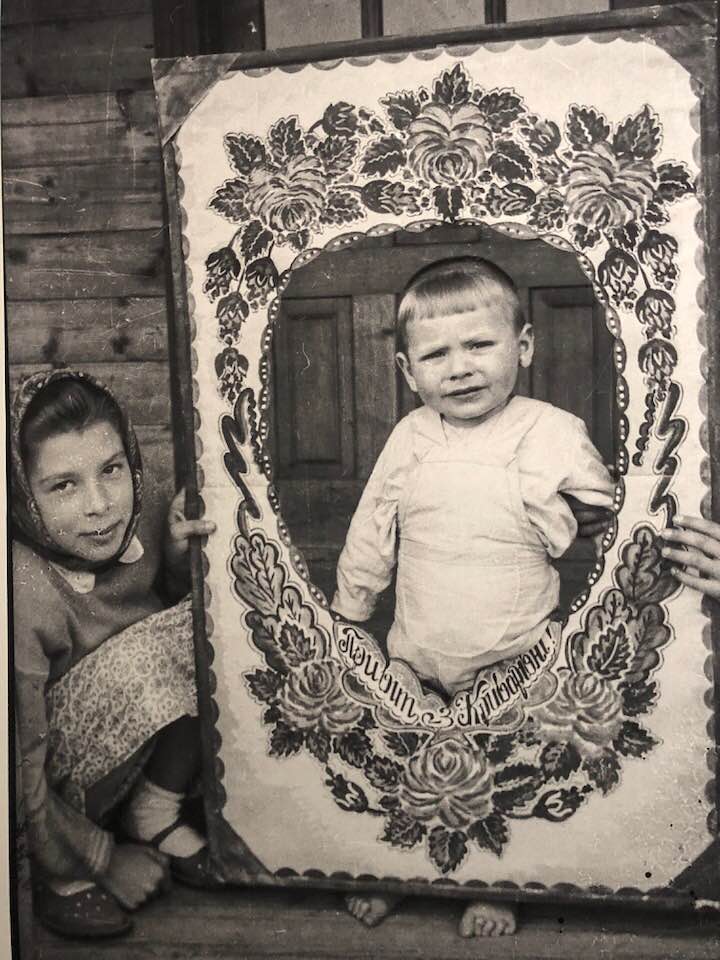

Her work as a photographer endeared her to the villagers, who often asked her to take pictures of their families, children and homesteads. Paraska always obliged, thus she unwittingly began recording Hutsul life and Carpathian landscapes.

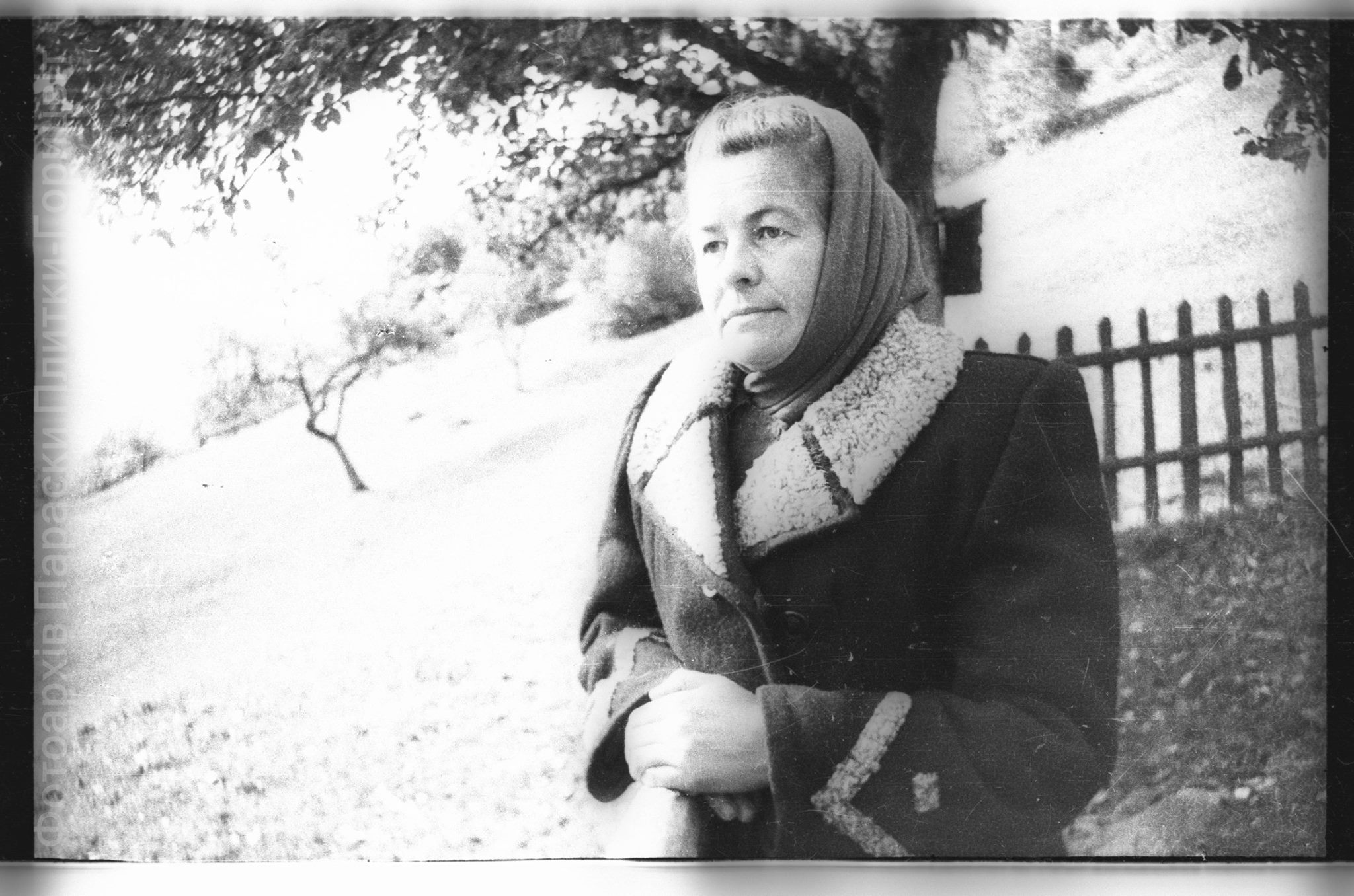

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit’s archive consists of photographs of smiling villagers, from rosy-cheeked infants to poised or cheerful elderly villagers. She documented birthdays and funerals, religious holidays and family events. Everything that surrounded her – people, animals, trees, bushes, mountains – found their way into her photographs.

Religion, Hutsulshchyna, India & handwritten books

Religion occupied a special place in Paraska’s life, perhaps due to the suffering and hardships that she had endured in the remote Gulags. She painted icons, gifted them to friends and the church. She led a simple, ascetic life, and material things were not important to her.

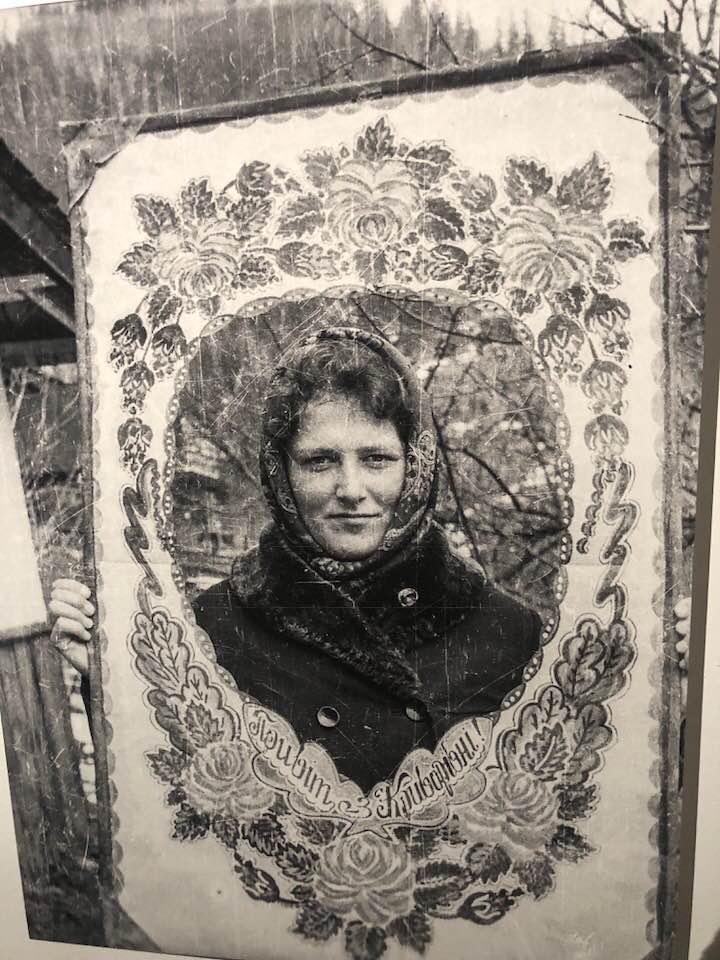

In the early years of the 20th century, photo stand-ins or face-in-hole boards were very popular in photography, and were often used at fairs, festivals to capture amusing images of persons who wanted their picture taken. Paraska created her own boards, two with no inscriptions and two with – “Greetings from Kryvorivnia” and “Greetings from the Carpathians”.

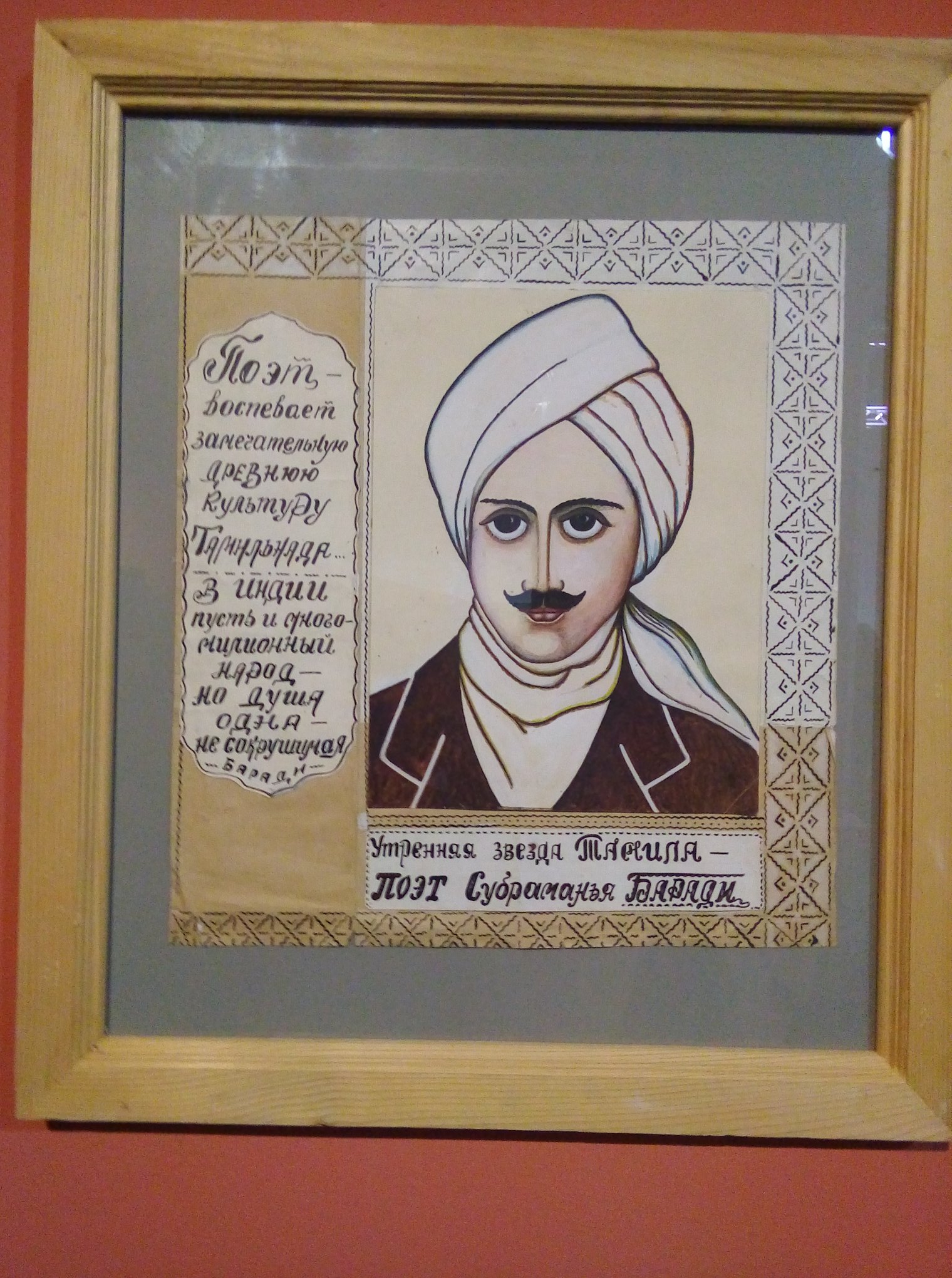

Paraska was a gifted artist and created lifelike figures and animals inspired by her Hutsul environment and exotic India.

Her photographs bear witness to a historical era that has vanished, while her writing, paintings and figures document the traditions of the Hutsuls. Paraska’s work illustrates local life and customs against the background of major historical changes.

In 1947, India gained its independence, and as a sphere of Soviet influence, was constantly in the news. Programs about India and Indian music were broadcast on the radio, and Indian films were aired daily on Soviet television.

Paraska was fascinated by Indian culture, and especially by Mahatma Gandhi and his philosophy. She wrote a six-volume novel, Indian Glows, about the travels and adventures of two Hutsuls in India, as well as a graphic series Adventures in the Indian Jungle and Leaders of a Peaceful India.

Paraska’s legacy also includes about 500 manuscripts. She illustrated the books herself, created the graphic designs and leather covers, which are decorated with patterns, calligraphic inscriptions and embroidery. Most of them are written in the Hutsul dialect. Paraska even began compiling a dictionary of the Hutsul dialect, so that her texts could be understood by the general public.

The end of a small vibrant world

Painful memories of interrogation by the NKVD, long years of suffering and hunger in the Siberian Gulags, and the dismal greyness of life in Soviet Ukraine could have broken Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit’s spirit. On the contrary, her indomitable will created a small world that she painted in vivid colours, filling it with joy and kindness and capturing it in its true light.

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit died in her village, in extreme poverty, alone and almost blind, on April 16, 1998. She is buried in Kryvorivnia and her modest home has been turned into a small museum.

It was only a few months after the independence of Ukraine, in April 1992, that Paraska Plytka Horytsvit was officially rehabilitated.

Hutsul life (cont'd)

Legacy & exhibitions

After Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit’s death in 1998, Oleksandr Chaika, who was studying her life, passed his research on to filmmaker Maksym Rudenko.

A few years ago, artist Inha Levi, Maksym Rudenko and Kateryna Buchatska discovered Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit’s archive during a trip to the Hutsul village of Kryvorivnia. They found thousands of negatives in a dusty old box hidden in the corner of a room. The team then spent hours, days and months cleaning these items and processing the negatives into photos, all of which finally resulted in an exhibition dedicated to Paraska Plytka-Gorytsvit - Overcoming Gravity - in Mystetsky Arsenal in Kyiv. It became hugely popular, exploring a previously unknown artist and opening up new aspects of Ukrainian culture to the public. Subsequently, the exhibit travelled to major cities of Ukraine.the

“Paraska’s contribution to the development of art is much greater in the context of feminist art and the nonconformist movement of the 1960s. She did not use political slogans, but confirmed her worldview through art, through dialogue and her attitude to the immediate environment,” affirm the curators.

Using modern media, i.e. a camera, Paraska Plytka Horytsvit offers us an author’s vision of a vanishing world, of traditions and a particular lifestyle; she teaches us to travel without leaving the comfort of our homes; and she shows us how it was possible to preserve some freedom of expression within the Soviet system. Her work illustrates the possibility of “overcoming the gravity of social laws and Soviet rules”.

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit (portraits)

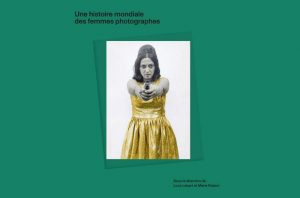

In November 2020, the French Editions Textuel published the much-anticipated World History of Women Photographers (Une histoire mondiale des femmes photographes), a collective survey presenting the works of 300 women photographers, including four prominent Ukrainian women: Sofiya Yablonska-Oudin, Iryna Pap, Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit and Rita Ostrovska.

Read also:

- Engineer Wienerberger’s unknown photographs of the Holodomor

- How a free-spirited country girl from Ukraine became an intrepid adventuress & 1930s travel blogger

- Kyiv circa 1890 in color(ed) photographs

- Hutsuliya – the vivid colours of Ukraine’s Carpathian mountaineers (Photos)

- Ukrainian mosaic: five unique ethnic groups

- Traditional Hutsul wedding in the Carpathians (photo report)