Over the past days, Belarus State television has shown several times footage with Belarus oppositionist Roman Protasevich confessing to his alleged “crimes.” The young man was pulled off a hijacked plane together with his girlfriend when returning to Vilnius from a holiday in Greece, incarcerated in the KGB prison in Minsk, and potentially facing charges of terrorism, which carries as a maximum the death sentence.

The first brief footage showed him visibly beaten up, already confessing to his “crimes”, and the rest that followed was to be expected.

The much longer footage broadcasted on June 3 was the end result: modeled as a sort of one-on-one television show Roman Protasevich gave a full confession to an interviewer, who pretended to be very understanding but actually showed quite clearly that he was merely an actor in a very nasty set-up and his interest was purely “professional.”

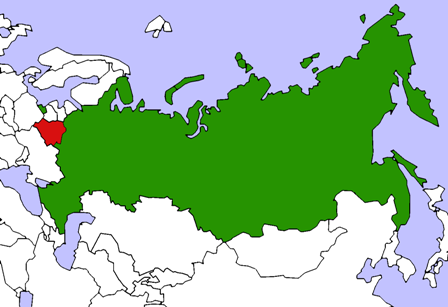

Andropov became head of the KGB in 1967, and immediately decided that his main task was to fight “ideological diversion.” He set up the Fifth “Dissident” Directorate, added new articles to the Criminal Code and developed the political use of psychiatry as a systematic means of repression.

Is there a resumption of political psychiatry in the former USSR?

In 1972 he hit hard at the dissident movement by arresting two of its leaders, Viktor Krasin and Pyotr Yakir. After several months of intense interrogations, under the direct supervision of Andropov himself, both cracked.

The method used was typical “Andropov-style”: Yakir was the son of Marshal Iona Yakir who had been executed in 1938, after which the whole family was arrested and the fourteen-year-old Pyotr was viciously tortured and subsequently sent to the Gulag. He was released by Khrushchev only in 1956. Severely traumatized he had become an alcoholic, and this was used to break him.

Krasin served nine years in the camps under Stalin, and being charged with “treason” he was threatened with the death sentence, something he could not face. His KGB interrogator skillfully turned him around, and in the end, both he and Yakir spilled their beans and gave a vast amount of information to the KGB. The dissident movement barely survived. After the trial both were brought to Andropov’s office for a chat; the cat playing with his mice in optimal format.

The method was used many times, in different ways.

In 1978 Georgian dissident and later Georgian President Zviad Gamsakhurdia was forced to a public recantation in which he stated "how wrong was the road I had taken when I disseminated literature hostile to the Soviet state” and in which he spoke of a “pharisaic campaign launched in the West, camouflaged under the slogan of 'upholding human rights.'"

In 1980, during my first trip as a courier to the dissident movement, I met a young thoughtful man in Leningrad, Valery Repin, whose main task was to provide help to families of political prisoners. He was arrested soon after my visit and left behind a young wife with a baby girl.

For a long time, he withstood the interrogations by the KGB, until one time he walked through the corridor to his next interrogation when “by coincidence”: the door to a room was open and he saw his wife with the baby standing there. The door was quickly closed, and his interrogator apologized for the mistake and added: “we have arrested your wife too. Your child will go to a State children’s home.”

That moment Repin cracked and named dozens of dissidents.

In the mid-1980s the KGB used yet another trick to break people. Political prisoners who had served their sentence were arrested again, sometimes on the day of their release, and told either to sign a statement and refer from any further activity or to face a new term of imprisonment. Not all could withstand the pressure. They also used so-called ”pressure cells,” where political prisoners were locked up with hardened criminals with the task to beat them up and thus force them into a confession. Undoubtedly the same method is used today.

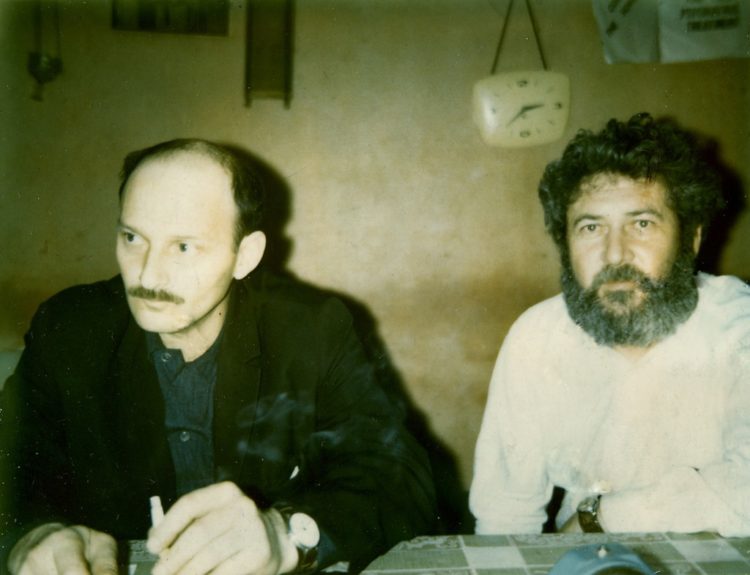

Viktor Krasin took the courageous step in 1983 to publish a short book in which he explained how he had been broken. The booklet, “Sud” (Trial), was published by a fellow dissident, Valery Chalidze, who had emigrated to the United States and felt it was necessary to also hear Krasin’s story. Definitely, not all agreed with him, and even ten years ago when I edited and published the much more extensive memoirs of Krasin, titled “Duel – Notes of an Anti-Communist,” still many could not understand why I took such an effort to help him publish his book.

Working with Krasin on his book was not easy. Because although he seriously tried to be honest about what had happened and understood that nothing could take away the enormous damage he had inflicted on the dissident movement, he still tried here and there to “upgrade” himself by writing nasty things about other dissidents. In a way, he wanted to “equalize” his own mistakes by promoting mistakes by others. In several instances, I intervened and refused to include the text, which made him very angry and upset, but in the end, he conceded.

The same has now happened to Roman Potrasevich. He is in hell, and there is no escape. The Belarussian KGB are faithful heirs to Yuri Andropov, and they will play with him as long as they wish.

The fact that they have his girlfriend will make things only worse – it is a repetition of the Repin scenario. In the end, they will spit him out when he is no longer needed. But he won’t be able to rejoin his friends and earlier social environment, and he won’t be able to look at himself in the mirror. His life will be in shambles, and one can only have pity on him.

The perfidiousness of the Lukashenka regime knows no boundaries, and I fear much more will be coming, alas. Put on your seat belt.

No, Belarusian dissident Protasevich is not a neo-Nazi. But the Kremlin sure wants you to think so