History weaponized

Just as heavily armored “little green men” invaded and occupied Crimea, and Russian tanks entered eastern Ukraine to wage war against the Ukrainian Armed Forces, another silent front opened in the classrooms of Crimean and Donbas schools.

The occupant administration removed the Ukrainian language and history from curriculums in the schools of the occupied Donbas, justifying it by a “decreasing popular demand.” Textbooks on Ukraine’s culture and history were replaced by new ones, brought in by Russian “humanitarian convoys” – those that are also reported to supply separatist fighters with weapons and ammunition.

Classes in Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar have met the same fate on the occupied peninsula, freeing up space for new Russian language classes and pro-Russian “patriotic” and military education.

[boxright]

A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics

[/boxright]

This occurrence is nothing new in Ukrainian history. One of the teachers in Donetsk fittingly compared the suppression of Ukrainian culture and language in schools to the Soviet period.

Already back then the USSR authorities closed Ukrainian schools en masse, Russian language teachers received higher wages than the Ukrainian ones, and dissertations were possible to defend only in Russian, to pick just a few examples from the post-war period. And we can go even further back in history – the Executed Renaissance of the 1930s, the suppression of Kobzarism, the 1876 Ems decree by Tsar Alexander II censoring Ukrainian language books, just two years after banning education in any language but Russian…

We can follow this common thread unfold in Russo-Ukrainian common past for hundreds of years.

The suppression of the Ukrainian identity in the Occupied Territories is therefore merely a continuation of Moscow's centuries-old strategy to uproot it.

This strategy took on many shapes and adapted its justification to any given zeitgeist, but its goal remained unchanged.

The 18th-century tsars forcibly converted "schismatic" Uniates, whose faith was portrayed as a result of the corrupting Western influence, while the Eastern Orthodoxy – preached in Russian and administrated by the Russian Most Holy Synod – was the only true faith of the Empire. Ukraine was termed “Little Russia,” while its inhabitants were presented merely as one of the constituent parts of the Russian nation.

However, the Bolshevik revolution and its internationalism forced a renewed discourse – now, the Russian-speaking proletariat in the cities represented progress towards communism, hindered by the Ukrainian-speaking peasant class. Open nationalism came back into play with Stalin, who positioned Russians as the first and foremost nation in the Soviet Union, thus reintroducing open Russification.

[boxright]

[/boxright]

His successors attempted to veil this strategy as “Sovietisation”, but the effect remained the same – an encroachment on the Ukrainian culture, history and language as excesses of “bourgeois nationalism.”

Finally, it stands to mention one discourse used particularly often by the Kremlin propaganda, that is equating Ukrainian nationalism with the World War II Ukrainian Insurgent Army and through it to Nazism. Through oversimplification and manipulation of history, displays of Ukrainian national identity are then described as a resurgence of fascism and Nazism, and there is no better defender from fascists than Mother Russia.

The current “Russkiy Mir” ideology does nothing more than to build on this legacy of past centuries. With little regard to ideological coherence, Stalin, Lenin, tsars, and the Orthodox faith are equally venerated and reshaped into a sense of nostalgia for the times of strength, power, and unquestionable authority.

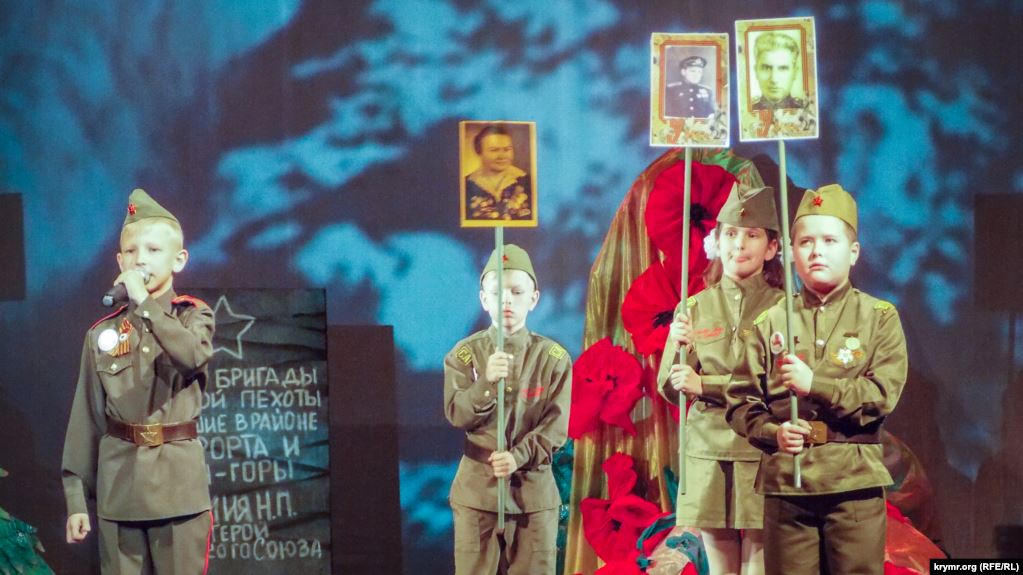

Constantly fuelled fears of the popular (and mutually interchangeable) trio of enemies, that is fascism, Ukrainian nationalism and the West, foster a siege mentality and justify the militarization of society. So just as Ukrainian language classes are replaced with the Russian language, patriotic and military education, so is the Ukrainian identity replaced with loyalty to Russia, devotion to authority, and veneration of war.

Building a new generation

As we discussed in an earlier

article, this strategy goes beyond a mere disinformation campaign. Rather than coercing the population of the Occupied Territories into accepting a set of policies, a sort of “virtual reality” is created through medial, social, and political manipulation, convincing the population of the necessity and desirability of such policies, even of accepting a given identity.

Any other points of reference, which may disrupt the created reality and therefore disrupt the building of the desired identity, must be taken out of the equation.

In some aspects, the strategy in Crimea and Donbas differs.

On the peninsula, children are raised like any other citizen of the Russian Federation. Yunarmia plays a vital role in promoting military-patriotic education, just like anywhere else in the country. Paramilitary and cadet classes are established all the way down to kindergartens, with military officers or ex-officers serving as instructors.

Access to Ukrainian and Tatar language and history education is suppressed as not to interfere with identity building.

In the occupied Donbas, however, there is still a certain sense of regionalism.

However, the omnipresent veneration of the Great Patriotic War in both instances serves to ground all of the content in history with black and white morality, teaching young generations who their idols and enemies are from the very beginning.

Why this is happening in Crimea is not difficult to deduce.

Moscow’s intention is to integrate the peninsula into the Russian Federation, therefore its inhabitants should not deviate from those of other regions. Its strategic and military value can be seen as a further reason for the militarization of its population.

from the pro-state media keeping the flame going.

At the first glance, the efforts in Donbas seem to raise new citizens of Donbas and Luhansk, not of Russia. The children in "DNR" are indeed taught to be patriots of the Donetsk People’s Republic.

However, as the new "DNR" doctrine states, Donbas is, and always has been, Russian. And this "Russian Donbas" is a merely younger brother or a subdivision of the greater Russian family. Just a continuation of the same old strategy, where Donbas serves as a microcosm for that Ukraine, which the “Russkiy Mir” ideology wants to shape.

Regional or Russian identity?

The question is, which of these two identities, the regional or the Russian one, is stronger?

According to a recent opinion poll in the Occupied Territories, when the respondents were asked to choose between joining Ukraine, Russia, or remaining independent, more than half of them stated the desire to join the Russian Federation, while only 12% wished to rejoin Ukraine.

[boxright]

Facts & figures in occupied Donbas. Is reintegration a realistic prospect?

[/boxright]

This also represents a serious challenge for Ukraine's future reintegration of the Occupied Territories. It poses not only the risk of a resurgence of violence but also a potential conduit for Russian activities even after Ukraine reclaims occupied Donbas.

This means that the educational and social efforts will play just as important a role in the reintegration as the security or economic ones.

Another dangerous side of this strategy is that it increases the risk of child soldiers. Reports indicate that dozens of minors, some younger than fifteen, joined separatist armed formations, while their training included shooting from rifles and planting mines.

A Ukrainian captured by the Orthodox Army witnessed boys at the age of fifteen among them, as well as underage girls training to be snipers and bragging with numbers of kills. The circumstances of their recruitment remained mostly unclear, though it likely involved a combination of volunteering and coercion. The current Russian “educational” efforts instill militaristic values into the Donbas youth, and thus significantly increase the likelihood of the former.

The West has been long accustomed to seeing Russia merely as a "hard power." Here we can see that its "soft" capabilities cannot be underestimated, especially in its Near Abroad. Moscow indeed presents an alternative to the Western liberal democracy, based on the Russian superiority, tradition, faith, devotion to authority, and to the country's past.

If the new generation is denied access to alternative reference points, such as through embracing their Ukrainian identity, they have no choice but to accept the only "reality" offered to them.

Read more:

- Stolen childhood: Russian propaganda and militarization of Crimean youth

- Parades and propaganda: how Russia erases the Ukrainian identity of kids in occupied Crimea

- Ukraine has not “lost” uncontrolled Donbas yet, new poll shows (2016)

- Most people in occupied Donbas prefer reintegration with Ukraine, new survey shows (2019)

- Facts & figures in occupied Donbas. Is reintegration a realistic prospect?

- How Russia militarizes minors in occupied Donbas