- that there is no contradiction between an ethnic and civic nation;

- why he believes in the "third Ukraine";

- that Ukraine is a country where the adrenaline is always high and where capitalism is "by default";

- why the fate of the world is being decided in Ukraine now;

- the greatest thing that the EU achieved;

- whether we can consider Ukraine a European country.

This is part 2 of our interview; read part 1 here.

You have touched on the subject of nationalism, and here there are many interesting questions. Back in 2012 in Odesa, you said that the ethnic and civic concepts of nation-building are struggling in Ukraine, but each of them lacks the strength to win. You suggested a certain third concept. Do you still have this view?

Yes, I call it the third Ukraine. Not in the chronological meaning that there was first, the second, and the third, but between the two, between the Ukraine of the west and the Ukraine of the east. Ukraine of the center, both geographically, politically, and ideologically. To a large extent, I believe that Kyiv, as a city of two revolutions, became of this Ukraine of the center.

I like to repeat this phrase, as Professor Roman Shporliuk from Harvard once said: the peculiarity of Kyiv is that it speaks the same language as Donetsk, and votes in the same way as Lviv.

I speak of this third Ukraine as a certain potential, an opportunity. Whether it will be implemented depends on two factors: first, whether there will be a political project, and second, whether Ukrainian reforms will succeed.

This thesis about the third Ukraine was first expressed by Mykhailo Dubyniansky, a Ukrainian publicist.

I also think that after the Euromaidan Revolution, there is yet another city that represents this third concept of Ukraine: Dnipro. We have a new axis: Lviv-Kyiv-Dnipro. The question is whether we can continue this axis and how far it will last. The key cities are Kharkiv and Odesa. And they are very problematic ones.

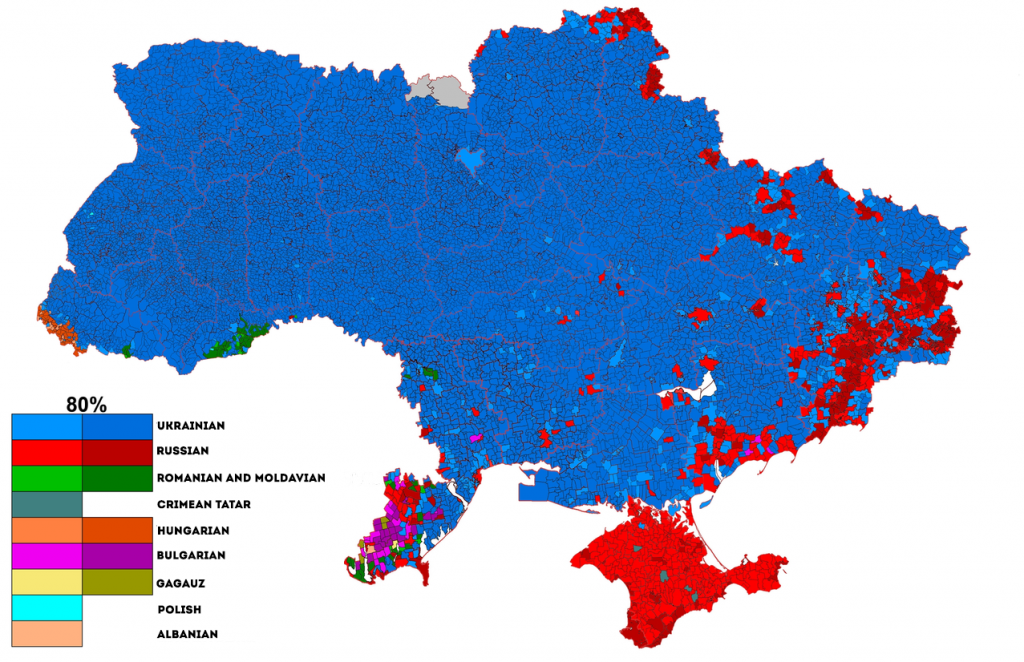

The Ukrainian nation is built as a civic nation, the only question is who will be the core of this nation. Conventionally speaking, Lviv or Donetsk. My preferred answer is Kyiv

Now on this thesis of a civic or ethnic nation. I don't think that's the right contradiction to make. Either this or that usually does not work. The question is how to make both the first and the second, not a zero-sum game, but a value-added game.

The division into ethnic and civic nations is largely artificial because there are almost no pure ethnic nations and almost no pure civic nations. Every ethnic nation has a significant proportion of national minorities, every civic nation is built around a certain ethnic core.

So my thesis is that the Ukrainian nation is built as a civic nation, the only question is who will be the core of this nation. Conventionally speaking, Lviv or Donetsk. My preferred answer would be Kyiv as the core of this nation. There is a potential for this, and to some extent, I even believe that Zelenskyy's victory is part of this very trend, although so far it is poorly realized.

Then there is another rather provocative question, such as the status of the Russian language. If we are talking about some middle way between Lviv and Donetsk, then what should this status be, if any at all?

I had a solution, but Ukrainian politicians were not ready for that. What will Ukrainian politicians do now – they will squeeze the Russian language out of all possible spheres, including the public sphere. I do not judge whether it is good or bad. I think it is ineffective.

The proposal which was developed earlier by a group of scholars from Germany and Ukraine, includes three simple theses: Ukrainian is the only state language, period; second, Russian or other languages may have the status of a regional language, but, and this is the third, only on the basis of certain procedures. Procedures mean that a local referendum must take place, which must be prepared for a long time.

Regional language means that two languages operate equally in those regions: Ukrainian and Russian, not just Russian. This means that all officials must be fluent in two languages and respond by the one addressed to them.

I believe that this thesis was good before the Maidan and the Russian aggression. But after the Russian aggression, Russian became the language of the enemy, so it is clear that the Ukrainian elite will displace this language and the chances of this liberal model are reduced.

I can say by historical analogies that the war that started in 2014 can play the same role in the history of the Ukrainian state as the Arab-Israeli war for Israel in 1967. It acutely nationalized that state. And I guess this happens one way or another in Ukraine, even under Zelenskyy. Even Zelenskyy, who says that “there is no difference” and “what difference [does it make what language one speaks].” Even he follows this path of nationalization.

Foreigners often associate Ukraine with oligarchs, corruption, seasonal workers, and war, according to the recent New Europe Center research. Here is a question to you as a historian: what can we add here that could be our productive business card?

My image of Ukraine is that of an extremely interesting country. A country where the adrenaline is always high.

I would mention another image that we forget: Ukraine as an anti-Semitic country. And this image is very strong, although it is often not expressed, but implied.

I'm not a professional image-maker but I can say as a historian. I think that the image of Ukraine is a country that, so to speak, tries and does not give up. She tries to deal with reforms, tries to deal with war, with everything. It doesn't always work, but it's important that she not give up.

That is, my image of Ukraine is that of an extremely interesting country. A country where the adrenaline is always high.

Timothy Snyder once said very well that Europe is prose and Ukraine is poetry. It is not a mystery that life in the West is good but boring. Here it may not be good, but never boring. Ukraine is an adventure. The image of Ukraine is that of a good adventure. Something very important is being done here, something very interesting. There are no final results yet, but it is worth being here at this time.

Timothy Snyder once said very well that Europe is prose and Ukraine is poetry.

The impact of what occurs here will extend far beyond Ukraine. It affects all neighboring countries. First of all Russia, but also Moldova, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and the whole region. Because it is Ukraine that secures the stability of this region.

I will say one last thing. I think that the fate of the world is being decided in Ukraine now, without exaggeration, the fate of the dominant model. The world will follow an authoritarian-populist path or the world will return to what is called Western liberalism.

The issue of Western liberalism is very interesting. In particular, in the West there is a growing tendency, especially for researchers, to delve into the topic of socialism, even to promote it in some way, while in Ukraine, on the contrary, we are finally trying to build capitalism and build a middle class. And here is a certain divergence. Would you agree with that?

The divergence exists. I ask economists about this. Conventionally speaking, this is the dilemma we call Hayek or Keynes, whether it is the Chicago School or the London School. Is it bold capitalism or regulated capitalism? The economists say that the solution is rather simple, if not too simple: first Hayek, then Keynes.

When a country needs rapid growth to get out of this, then control must be minimal. But when it rises, then the state starts certain social programs. Now we have nothing to pay for these programs.Our property is not well protected, so our capitalism is not Chicago school, but, you know, western-style with cowboys so far.

But again, it is necessary that there be political forces that will build these projects. I do not see these forces yet. What is being done in Ukraine, in my opinion, is simply spontaneous capitalism, capitalism by default. Just as we have democracy by default and capitalism by default. Good capitalism requires one condition - protected property. And our property is not well protected, so our capitalism is not Chicago school, but, you know, western-style with cowboys so far.

Now I will move on to the question of a new political force that should fix this. Who should it be? I read a thesis of yours that it could be the new generation. But is there any potential in that generation, given its rebellious spirit? Even during the Maidan – it actively manifested against dictatorship, but couldn’t create a holistic political project.

First of all I really like your generation. It's like a compliment, but a true compliment. I believe that the emergence of your generation, in particular, you personally, is one of the greatest achievements of Ukrainian independence. This is serious, because it was impossible even ten years ago. I lived a little and I can see. You are already different, you are already behaving differently. This is a new quality.The emergence of your generation is like the anchor that anchored this ship on the course we are now on. The return of Russian or Belarusian realities is no longer possible, period.

There are, however, two problems with your generation.

First of all, you have certain traits that prevent you from forming political projects. This is, in particular, the fact that you are a generation of horizontal connections. Vertical hierarchy is alien to you. That is why political projects will always be difficult for you. Because the political hierarchy must be a hierarchy.

And second, it may be too early to expect anything from you. Because the way of such projects has to be the way of trials and errors. You need experience. There was no such generation that could come so quickly. All the time I give an example of the generation of the 60s. When it came to the 1968 revolution, it lost that revolution. But twenty years later, it came to power in elections. They were already 40+ years old. Then they started changing this world. So I give you what is called in English benefit of the doubt. In a positive sense.

The emergence of your generation is like the anchor that anchored this ship on the course we are now on. The return of Russian or Belarusian realities is no longer possible, period. If your generation was in Russia or Belarus, the result would be interesting. In Russia and Belarus, this generation has not yet happened. People are the same, but you have the experience, they do not have this experience.

After Euromaidan we often stress that Ukraine is part of Europe, meaning also the EU. Perhaps you as a historian could explain: where does Europe really end?

We can criticize the European Union for many things, but the main thing it has achieved is "never again."

Europe means a lot of different things. Old Europe meant Christian Europe and Ukraine belonged to it because it was a Christian country. The fact that Ukraine became a Christian country immediately included it in the European space. There is a very good study by the German historian Christian Raffensperger. He shows that ca. 75% of marriages made by Kyiv kings were marriages to the West.

Interwar Europe was more like a Europe of anti-liberalism, a Europe of communism or fascism. And in that sense, Ukrainians were also in that Europe, because they had both.

For me, contemporary Europe means not only prosperity but above all the absence of war. A major source of war in Europe was the conflict between France and Germany, which began at least with the Franco-German War of 1870, if we disregard Napoleon. Now such a war is impossible.

We can criticize the European Union for many things, but the main thing it has achieved is "never again."

As for Ukraine, I believe that Ukraine is European because it has managed to reconcile with the Poles. Whatever we may say about the current relations between nowadays Poland and Ukraine, still, generally speaking, the Polish-Ukrainian reconciliation has taken place. You can't imagine a war for Lviv or Przemyśl now. And that was the reality a few decades earlier.Generally speaking the Polish-Ukrainian reconciliation has taken place. You can't imagine a war for Lviv or Przemyśl now. And that was the reality a few decades earlier.

I can quote brilliant intellectuals in the 1970s, who were afraid that with the fall of Communism, the Polish-Ukrainian war for Lviv would start immediately. Luckily, it never happened. There is no Ukrainian politician who claims that Przemyśl is a Ukrainian city; likewise, I do not know any Polish politician who sees Lviv as a Polish city.

Unfortunately, that is not the case with Russia. There are many Russian politicians and intellectuals who claim that Ukraine has territories that must belong to Russia. If they would think otherwise, there would be no war in Donetsk and no annexation of Crimea.

If I may say so, Ukraine is European in the west, there is no Polish-Ukrainian war there, and it is not European in the east, because a war is going on there.

How far will Europe spread to the east? The key issue is Russia. The whole of Europe is built on a system of reconciliation. There was French-German reconciliation, there was Polish-German reconciliation, there was Polish-Ukrainian reconciliation, the key is Russian-Ukrainian and Russian-Polish reconciliation. Definitely, we have to strive for it. But it can not happen now while Putin is in power, He does not understand the language of reconciliation, but only the language of force.

But my thesis is also that, before and if Russian-Ukrainian reconciliation would ever happen, Ukrainians have important homework to do, and that is Ukrainian-Ukrainian reconciliation.

This publication is part of the Ukraine Explained series, which is aimed at telling the truth about Ukraine’s successes to the world. It is produced with the support of the National Democratic Institute in cooperation with the Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, Internews, StopFake, and Texty.org.ua. Content is produced independently of the NDI and may or may not reflect the position of the Institute. Learn more about the project here.

Read also:

- Why post-Euromaidan anti-corruption reform in Ukraine is still a success

- Seven years after Euromaidan: how much has Ukraine progressed?

- Historian Yaroslav Hrytsak: “Ukraine is in a state of permanent revolution”

- The lessons of Euromaidan: why the Belarusian revolution is at a stalemate

- Decentralization — a true success story from Ukraine

- 55% of polled EU citizens support Ukraine’s EU membership, but negative perceptions still prevail

- More than half of Ukrainians see Ukraine’s future in EU, only 13% with Russia: Poll

- How Ukraine can become a European Silicon Valley

- Ukraine in review: the biggest stories of 2020