In the mid-1970s, political confrontation between the USSR and the West reached such heights that it threatened to escalate into a world war. Therefore, after lengthy negotiations, 32 European countries (except Albania), the USA, Canada and the Soviet Union signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in Helsinki on 1 August 1975.

The Helsinki Final Act finally fixed the borders that had been established in Europe after the Second World War. In addition, the USSR became a commercial partner of the West. In exchange, the Soviet Union pledged to observe the humanitarian section of the Final Act, in particular, human rights under the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights from December 10, 1948, Article 19:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

On 12 May 1976, Andrei Sakharov and his supporters founded the Moscow Helsinki Group. The Ukrainians came second, on 9 November 1976. Later, on 25 November 1976, a Helsinki Group was founded in Lithuania, on 14 January 1977 – in Georgia, on 1 April 1977 - in Armenia. In Poland, an independent public group – the Workers’ Defense Committee, later changed to Committee for Social Self-defense – had been active since September 1976. In January 1977, a human rights association called “Charter 77” was launched in Czechoslovakia. A special Congressional committee was created in the US

Thus, the Helsinki human rights movement quickly became international.

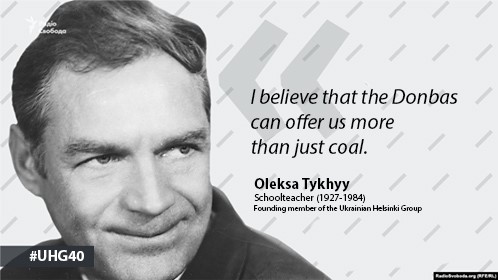

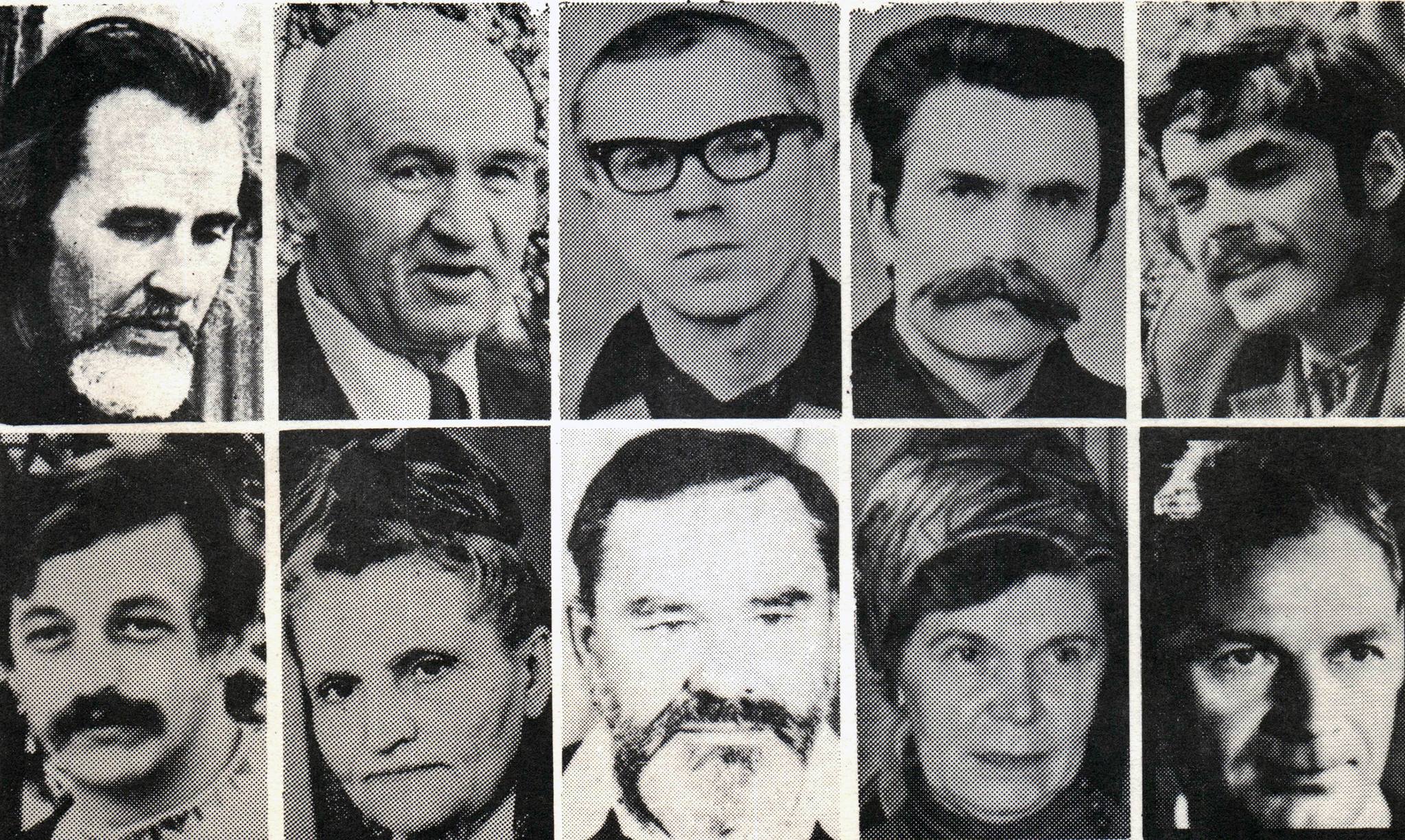

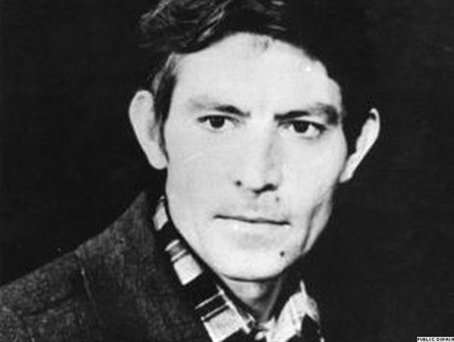

The legal human rights organization in Ukraine was founded on the initiative of writer and philosopher Mykola Rudenko, Soviet Army General Petro Hryhorenko, chemist Oksana Meshko, science fiction author Oles Berdnyk, and lawyer Levko Lukyanenko. The group generally had 49 members during its entire existence.

The state for man, and not man for the state

On 9 November 1976, the members signed a Declaration to promote the implementation of the Helsinki Agreements and Memorandum No.1. The main goal was to acquaint governments that had participated in the Helsinki Conference and the international community with human rights violations in Ukraine, and protect the rights of Ukrainian citizens living in other Soviet republics.

Memorandum No.1 exposed the crimes of Communism: genocide and ethnocide, forced dispossession, the Holodomor of 1932-1933, political repressions of the 1930s, elimination of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), extermination of civilians by the KGB disguised as “insurgents”, total Russification, and persecution of Shistdesyatnyks. The members also pointed to a constitutional legitimacy that would allow Ukraine to leave the USSR.

Memorandum No.5 indicated that the essential attribute of a civilized state is the presence of opposition, and the basic principle should be “The state for man, and not man for the state”

. Activists demanded the right to leave and enter the country freely, the free flow of ideas and opinions, elimination of censorship, permission to create free associations and unions, release of political prisoners, and abolition of the death penalty.

Human rights activists initiated a revolution in the consciousness of citizens terrorized by the totalitarian Communist regime.

In authoritarian Soviet republics, people began behaving like free citizens, exercising their constitutional right to freedom of speech, press, demonstrations, and associations. Independent public opinions were voiced openly. Now, demagogic statements about “interference in the internal affairs of the USSR” became inadmissible as they violated fundamental human rights.

To liberate Ukraine from colonial rule

The group was engaged not only in human rights issues. As the global colonial system continued to disintegrate, the Ukrainian Helsinki Group reminded the world that Ukraine was still subjugated to a foreign power, and raised the issue of recognition of Ukraine by the international community.

In an interview with Hromadske Radio, UHG member Myroslav Marynovych stated that for him the issue of Ukraine’s independence and protection of human rights in the Soviet Union were one and the same:

“I have never distinguished between human rights and national rights. When I was recently writing my memoirs and looking through materials in the Chronicles of Current Events, there were quotes by several dissidents, including Ukrainians, who stated that human rights and national rights were identical. It was much later that activists began distinguishing between them, and even opposing them.”

According to UHG member Yosyf Zissels,

“the purpose [of the UHG] was Ukraine’s liberation from colonial rule, but the methods of this struggle took on a human rights dimension. We found a weak spot and started working with that.”

Read also: Ukrainian dissident Krasivsky: Russia is our historical enemy. Only by fighting back can we survive

Movement unites different nationalities

A very important factor in the creation of the movement was the Soviet suppression and liquidation of Ukrainian armed resistance in the early 1960s, incarnated by what remained of the UPA Army. The movement united not only Ukrainians, but also representatives of Russian and Jewish communities, who joined the Group after the arrest of several of their members. This was very important because it meant that not only Ukrainians, but also other ethnicities that lived in Ukraine were ready to protest.

Thus, it brought together people of different nationalities with different views who understood that no human rights could exist under colonial rule because only an independent state could guarantee basic freedoms.

Before, western countries believed that Ukraine was the USSR’s zone of responsibility, and did not have a liberation movement similar to those in Africa or Southeast Asia. After the creation of the UHG, things began to look a little different.

All members repressed

In response to the activities of the Ukrainian opposition movement, authorities resorted to mass repressions – in 1977, prominent members of the organization were arrested and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

As a result of large-scale repression and persecution, the majority of UHG leaders were imprisoned as of 1979. Moreover, not only did the Soviet totalitarian regime fabricate political cases against them, but also charged them for criminal deeds in order tarnish their reputation.

As of March 1981, all the members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group were either in camps or in exile.

Despite mounting pressure and mass arrests, the Group did not disband, but continued to expand, recruiting new members even in camps and exile; two foreigners joined the group in 1982, and six more in late 1987.

Of all the Helsinki groups in the USSR, only the Ukrainian one continued to operate in the camps.

Documents were smuggled out of captivity. The External Representation of the Helsinki Group published a monthly newsletter “Bulletin of Repression in Ukraine”, the Washington Committee supported rights guaranteed to Ukraine under the Helsinki Agreements, the Vasyl Symonenko Ukrainian publishing house “Smoloskyp” (Torch) published the Group’s documents in Ukrainian and English, and news about the Group was broadcast regularly on Radio Liberty. Ukrainian human rights activists were not forced to go underground and signed documents in their names, openly declared their position and demands, appealing to Soviet law and international legal documents signed by the USSR. The Ukrainian Helsinki Group released 30 memorandums, declarations, manifestos, appeals and newsletters.

On 23 September 1981 in a report to the 13th National Congress of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies in Pacific Grove, California, Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky, famous professor and political scientist spoke about the Ukrainian movement:

“... there’s no doubt that facts testify to the importance of Ukrainian dissidents. The sacrifice of these brave men and women demonstrates the indomitable spirit of the Ukrainian nation. Their fight for human and national rights is in line with global progress in universal freedom. Ukrainian dissidents believe that truth and freedom will overcome. People who are lucky enough to live in free countries should believe just as much.”

Predecessor of the first political party

During Glasnost and Perestroika, most Helsinki dissidents were released and resumed their activities, which quickly took on a political character. On 7 July 1988, members established and officially registered the Ukrainian Helsinki Association, which in 1990 transformed itself into the Ukrainian Republican Party, the first political party in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian civic group to promote and implement the Helsinki Agreements is a landmark in the history of the Ukrainian liberation and human rights movement. The tireless work of its members, along with other factors, led to the independence of Ukraine, and contributed to the rule of law and the development of civil society. On 1 April 2004, the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union was established as an Association of public human rights organizations. Today, 30 human rights organizations are represented in the Association.

Updated from this article