The Crimean Peninsula has long suffered from water shortages, but these are now often exacerbated by the ever-more frequent winters with little-to-no rain or snow. In the last several months, under Russian occupation, those difficulties have become critical: according to Russian officials, the region has seen its reserves of potable water decline by 60 percent and will entirely run out of supplies of this critical natural resource sometime in July or August (Gazeta.ua, May 21). The situation is creating a serious public health crisis in Crimea and could prompt Moscow, which has few other options, to engage in a new military action against Ukraine to gain access to water supplies, especially as Ukrainian officials and commentators have made clear that Kyiv is not prepared to sell water to the occupation authorities (Moskovsky Komsomolets, May 19).

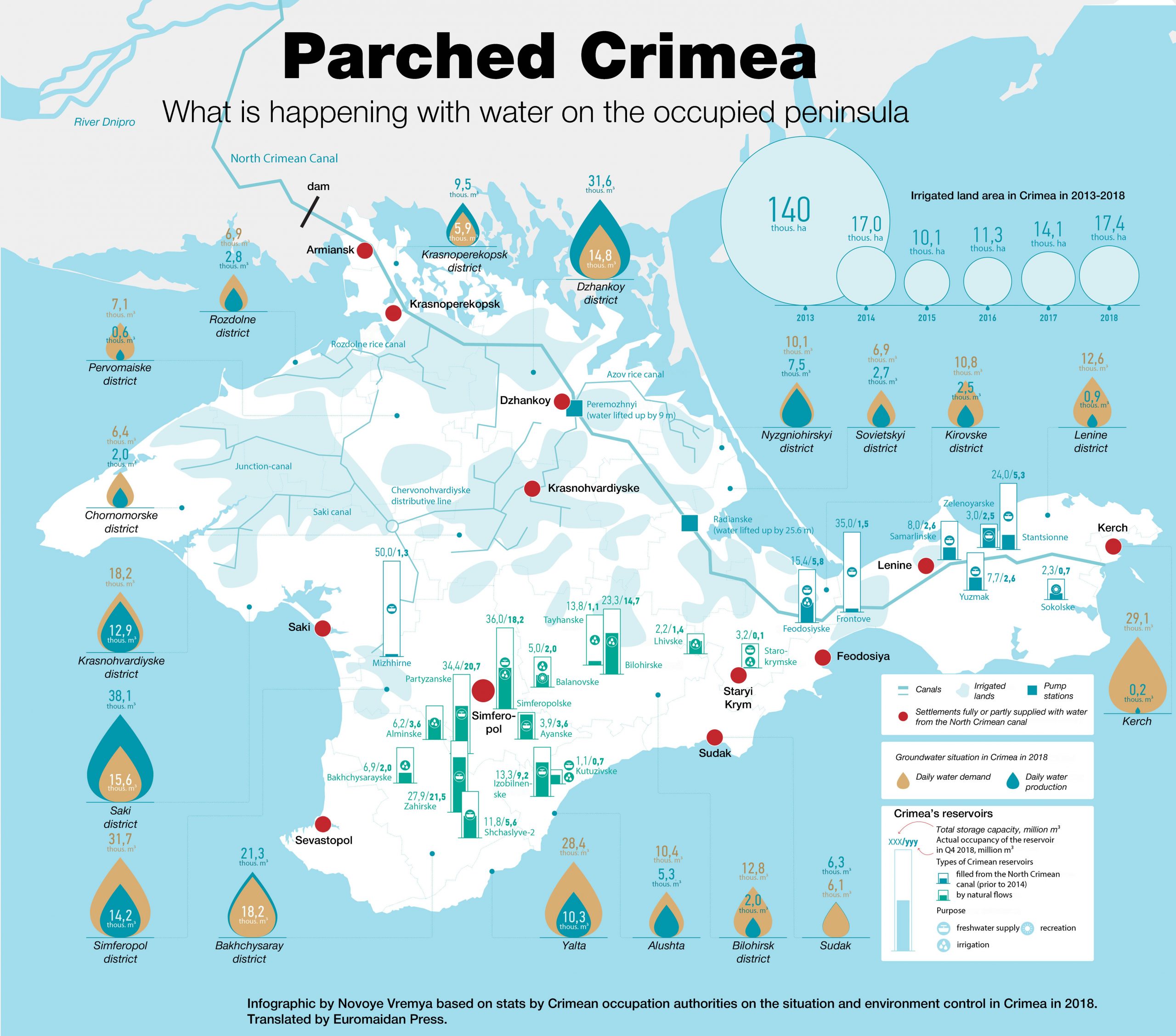

This crisis has been building for some time (see EDM, February 26; Geopolitical Monitor, April 24). Until the Russian annexation in early 2014, 85 percent of the drinking water for Crimean residents came via the North Crimean Canal, from the Dnieper River. But after Russian forces arrived, Ukraine abruptly ended that practice, forcing the occupiers to rely on local wells, ground water and reservoirs. The peninsula has 22 reservoirs, with a combined capacity of 334.2 million cubic meters. At present, however, some of them have already completely dried up, and the remainder are at critical levels. They were about two-thirds full a year ago but have reportedly been drawn down to less than a third now (Apostrophe, May 17).

The occupation authorities blame the current crisis not only on Kyiv’s intransigence but also on the enhanced need for water during the pandemic. Ukrainian officials and experts, however, disagree with that contention. The water shortages, in their view, are entirely the result of the occupation itself. If it ends, so too will the water crisis. As Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Oleksii Reznikov recently put it, “[W]ater for Crimea from other parts of Ukraine will come only after de-occupation. This is the united position of the government” (Gazeta.ua, May 21).

The Kyiv-based writers note that the 1949 Geneva Convention specifies that “responsibility for providing the population” with such necessities as safe drinking water lies with the occupying state. If Ukraine were to give water to the Russian occupiers, these writers fear, that would constitute recognition of the occupation. In fact, that is not necessarily the case: Israel, for example, provides water to Palestinian areas under its control but does not thereby recognize Palestinian claims. Nonetheless, Kyiv believes otherwise and is unlikely to change its mind.

The Russian occupation authorities currently are trying to address the problem by drilling more wells and extending pipelines into cities; moreover, they have announced plans for establishing water-purification plants. But groundwater levels in much of Crimea have fallen dramatically. They are currently too low for fruits and vegetables to be planted in the northern half of the peninsula, and the construction of purification plants like those in Israel will not be completed for some time. Meanwhile, Crimea faces the prospect of water shortages for both agriculture as well as the resident population (Ren.tv, May 21; RIA Novosti, May 19).

Trending Now

Not only is Crimea running out of water and losing any chance to save the situation on its own, Yury Smelyansky of the Kyiv Institute for Black Sea Strategic Research asserts, but the occupation authorities have often played up this issue in order to put pressure on Kyiv via Europe. Indeed, he notes, what Moscow outlets say about water for Crimea has paralleled Moscow’s efforts to expand its control into other parts of Ukraine. When Putin invaded Ukrainian territory in 2014, he expected to seize a much larger portion of it than he was able to, including the places from which Crimea had historically received its water. That pattern raises the question as to whether the current “hysteria” in Crimea about water shortages reflects only that direct problem or presages a new Russian move against Ukraine (Apostrophe, May 17)

Much of what the occupiers are saying now is in the realm of fantasy, Smelyansky contends. In order to power enough water-purification plants to provide a daily minimum 16 liters of water for each Crimean, the Russian authorities would need to construct “about ten atomic power stations,” something beyond Russia’s capacity and an action sure to spark international outrage given the environmental consequences of such a move. Meanwhile, Kyiv will not shift its position either, no matter how much pressure the West and Moscow put on it to do so. That is because there are looming water shortages in Ukraine itself, and giving water to the Russian occupation would only exacerbate them.

That increases the possibility that Moscow may decide on a military option, a thrust northward into Ukraine proper to gain control of water for the peninsula before a full-scale humanitarian disaster hits later this summer. Indeed, such a resource crisis, if unaddressed, might prompt new Western demands for Russia to give the peninsula back to Ukraine. Both Russian and Ukrainian officials have talked about that possibility, with the former encouraged and the latter frightened by the fact that earlier this year, Ukrainian security officers found “a cache of weapons and explosives near the North Crimean Canal” (0552.ua, February 18; see EDM, February 26).

The water situation in Crimea was dire then; but it is even more so now. And consequently, the possibility that Moscow will launch just such a military strike cannot be ruled out, especially as the Russian authorities can currently count on the rest of the world being distracted by the coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, Moscow might calculate that it would be able to present any such move as a “humanitarian” gesture rather than as the naked military aggression it would so obviously be.

Read More:

- Ukraine’s water blockade of Crimea should stay, because it’s working

- Russia can’t solve Crimea’s water problem

- Putin moving from ‘Great Victory’ to hostility to entire world – and young Russians are ready to follow him, Ilchenko says

- Kyiv and Moscow square off over legal arrangements for the Black Sea

- A compromise with Russia that respects core Western principles is an illusion – James Sherr

- What if Russia wins in Ukraine? Consequences of Hybrid War for Europe (Part 1)

- The E40 waterway: Economic and geopolitical implications for Ukraine and the wider region