On April 24, the Ukrainian Parliament adopted a first reading of the bill “On Inland Water Transport,” finally codifying important planned reforms pertaining to riverine transportation in Ukraine—in particular, on the Dnipro River (Mtu.gov.ua, April 24). This new law creates a framework regulating the functioning and development of domestic riverways as well as launches a liberalization of this sector. If the bill passes its second reading (following additional input from interested businesses—UNIAN, April 24), Ukraine will come into compliance with the obligations found in its Association Agreement with the European Union, at last opening its river transportation market to foreign companies, external investments and foreign-flagged ships (notably, including military vessels) (Rada.gov.ua, January 17).

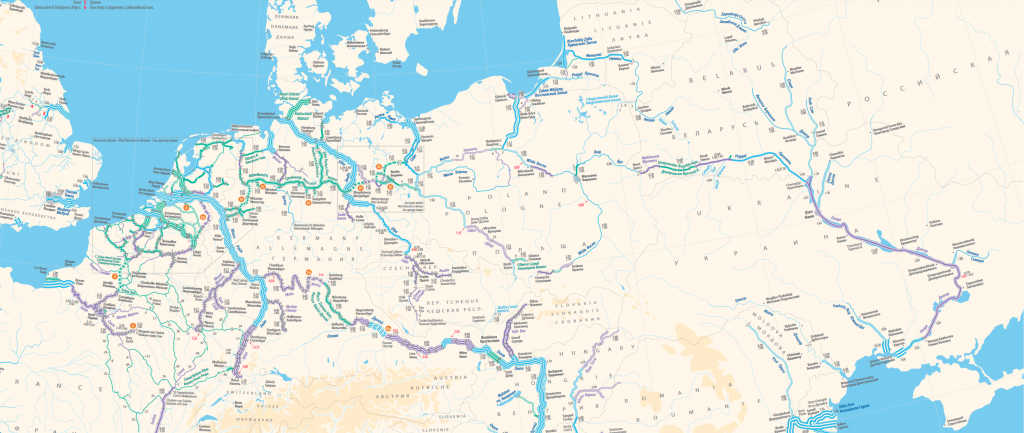

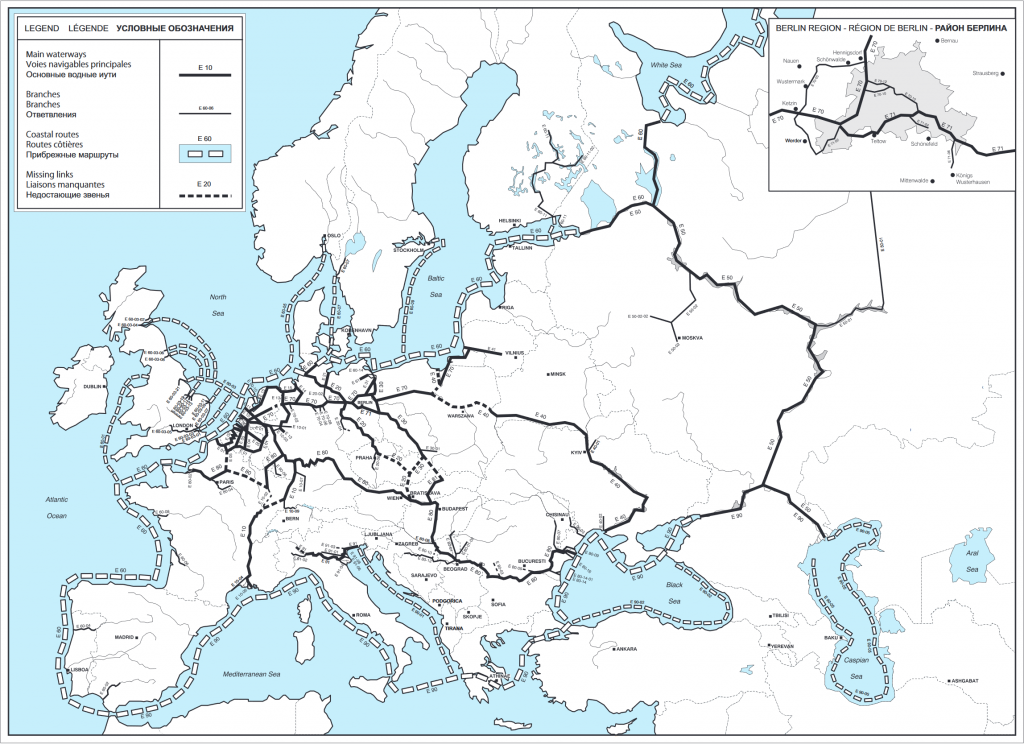

According to Vladyslav Krykliy, Ukraine`s minister of infrastructure, the law is instrumental for Ukraine’s economy as well as general compliance with European infrastructure norms and principles. Apart from the restoration of domestic shipbuilding enterprises and the creation of new jobs, the new law will importantly allow Ukraine to proceed with the realization of the so-called E40 waterway project. This more-than-2,000-kilometer-long route aims to connect the Black and Baltic seas, effectively bridging the Polish port of Gdańsk and Ukrainian Kherson via the Vistula River, Bug Canal, and the Pripyat and Dnipro rivers (see EDM, February 18, April 28, May 4). This project will permit the maritime transport of oil and oil products, fertilizers, wood, grain, metal and metal products, as well as other cargoes to Europe, Africa and Asia via the Baltic-Pontic Isthmus (between the Baltic and Black Sea).

Moreover, the waterway could be integrated with current freight flows across regional/trans-regional railway and road corridors. Greater use of riverine transport would also reduce road repair costs for Ukraine by one billion hryvna (over $37 million) over the next four years (Mtu.gov.ua, April 24).

The idea to link the two seas via the Baltic-Pontic Isthmus is hardly a novelty (see West, Russia face off in Belarus over Baltic–Black Sea waterway project). Ancient history aside, the first contemporary idea on the matter appeared in 1996 and was supported by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). These plans were again front and center in the “European Agreement on Main Inland Waterways of International Importance” (AGN) multilateral treaty, joined by Ukraine in 2009 (Cfts.org.ua, September 16, 2019). Between 2017 and 2018, the project became part of bilateral Ukrainian-Belarusian negotiations (Gazeta.ru, July 22, 2017).

Perhaps, the most discouraging aspect of the project is its cost, said to reach over $13 billion.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Infrastructure is considering several sources to finance the project. The government is ready to allocate 500 million hryvna ($18.6 million) annually during the next four years, which should be enough to conduct all the necessary upgrades. With proper dredging works, barges with carrying capacities of 5,000–6,000 tons would soon be able to navigate the Ukrainian section of the waterway (Biz.liga.net, February 13). Additionally, the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) are tentatively ready to invest in the project. Since the E40 fits in with planned trade routes connecting the Netherlands and Türkiye, Dutch companies are willing to participate as well.

Trending Now

Notably, the E40 could be integrated into the Three Seas Initiative (3SI), a coordinated collection of intra-regional infrastructure development projects that involves 12 EU members in Central and Eastern Europe (YouTube, September 17, 2018). With Poland a part of the 3SI, and Ukraine and Belarus members of the EU’s European Neighborhood Policy and Eastern Partnership, this project shows promise.

The E40’s value also comes from its numerous potential linkage options to other regional and transcontinental transportation corridors. Namely, the Ukrainian-Belarusian-Polish route could link to the European E70 waterway, thus connecting the Black Sea with Western Europe (Ukurier.gov.ua, May 12, 2016). The E40 might also be integrated with the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (Ukraine has been a part of this trans-Eurasian transit corridor since 2015). The project, connecting the Baltic, Black and Caspian Seas was already discussed with Chinese officials (Investinkherson.gov.ua, accessed May 12).

In this regard, the Ukrainian port of Kherson (at the southern end of the E40) could be developed into a key node of transcontinental trade. Plans are already underway to transform the city into a river logistics hub with a modern all year-round navigable river fleet (including small river icebreakers). Cargo flows via Kherson are expected to reach two million–four million tons by 2030 (Cfts.org.ua, February 6). Also, Nibulon, the only Ukrainian agricultural company with its own fleet, is ready to invest in the port, which may upgrade annual trade between Ukraine and Belarus to ten million tons (Ukrinform.ua, October 3, 2017). Additional plans include construction of a dry port and a potash fertilizer granulation plant, which will serve freight between the Middle East and Ukraine and Europe (Tavrianhorizons.in.ua, October 10, 2017).

In particular, the E40 could permit the passage of military vessels, including small-class North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ships, and thus overcome certain limitation stipulated by the 1936 Montreux Convention regarding international naval access to the Black Sea (Svpressa.ru, September 15, 2019). However, some challenges may arise—primarily related to the fact that Belarus is formally a treaty ally with Russia. Yet, given Minsk's behavior and recent steps, this could change: for example, on November 12, 2019, the ministries of defense of Belarus and Poland (a NATO member) notably discussed bilateral military cooperation (Mil.by, November 12, 2019).

Development of the project is likely to result in adverse actions by Russia. According to Rostislav Ishchenko, the E40 will directly challenge Russian trade across the Don–Volga route, potentially decreasing the latter’s importance (Zvezdaweekly.ru, September 18, 2019).

The E40 notably may lead to the revitalization of a centuries-old transcontinental transportation/trade corridor, connecting two important European seas and more deeply integrating Ukraine (and Belarus) into the EU’s infrastructural and economic frameworks. Yet, given outstanding financial, geopolitical and ecological obstacles to its completion, the concept of the E40 still requires deeper strategic analysis and higher levels of agreement between all the parties involved.

Read More:

- West, Russia face off in Belarus over Baltic–Black Sea waterway project

- EU emerges as leading donor for Partnership countries in fighting COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences

- What if? Hybrid War and consequences for Europe (part 1)

- Russia’s occupation of Crimea, Donbas war not “serious violations” in Council of Europe’s new sanctions procedure

- Europe fails to see Moscow using economics as a weapon not only against the former Soviet states but against it as well, Tsybulenko says

- Intermarium countries can no longer count on West to defend them against Russia, Honcharenko says

- Intermarium countries becoming Ukraine’s main advocates, Portnikov says

- Intermarium – an idea whose time is coming again

- Moscow worried about Ankara’s plans for canal bypassing Bosporus Strait

- 68% of Ukrainians want pro-European reforms even without EU membership prospect