That this horror for Ukrainian peasants was intentionally created by Stalin is commonly accepted. However, the political (and partly historical) debate whether Holodomor was a genocide of Ukrainians goes on. The reluctance of Germany in 2019 to approve a petition that demands the official recognition of Holodomor as genocide is the best example of this still continuing political struggle.

In this article we have already explained why Holodomor was not only a mass famine among Soviet peasants because of collectivization but was directed against ethnic Ukrainians specifically. Here are 18 countries that have officially recognized the Holodomor as genocide.

Yet, as the topic is researched more and more, new facts become available that not only prove further that Holodomor was genocide, but also amend the common narrative about unfortunate Ukrainian victims of Stalin’s madness.

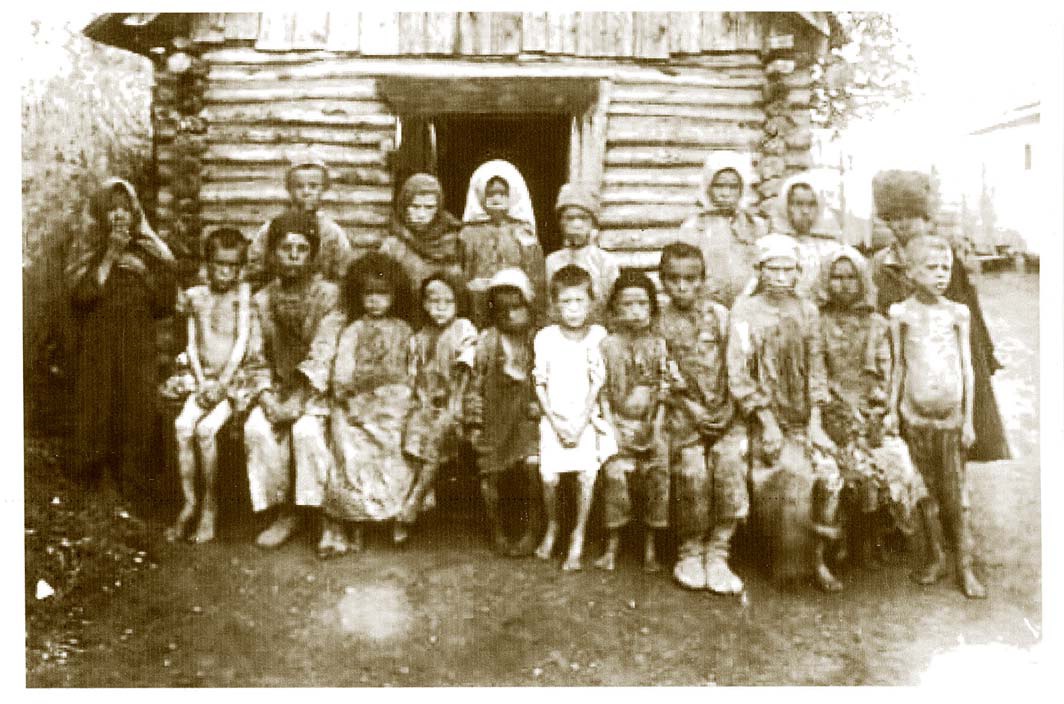

In fact, Stalin did this because he feared Ukrainians and their movement towards wider autonomy. Around 5,000 peasant revolts against the Soviet policy of collectivization with more than 1 million involved took place in Ukraine just before the Holodomor.

This largely overlooked fact proves that Ukrainians did resist Soviet occupation not only in 1917-1919 but throughout the 1920s and up to 1932 when the Holodomor was designed to finally break down that independent spirit.

Although not entirely successful, it was a devastating blow for the Ukrainian nation that is still visible in the Russified cities of Eastern Ukraine today.

Why revolts took place in Ukraine but much less frequently in other parts of the Soviet Union

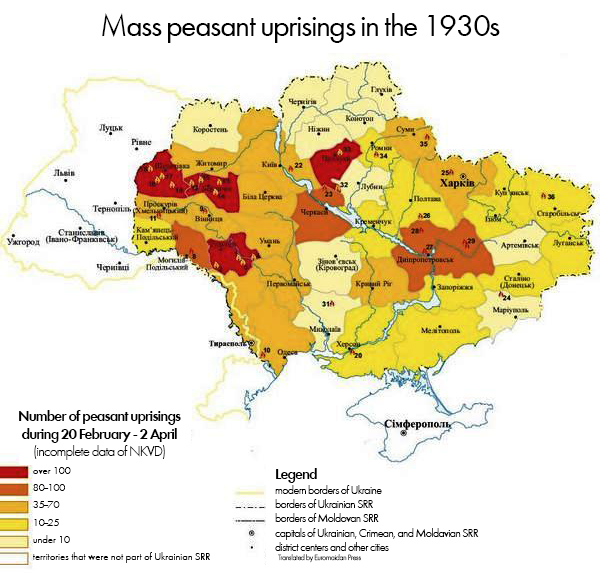

In 1932 Stalin was gradually losing control over Ukraine. The Communist Party was not entirely unified because local Ukrainian communists were often prepared to stand in opposition to the policies pursued in Moscow. Additionally, according to this article by Ukrainian historian Volodymyr Tylishchak, in the first seven months of 1932 alone, law enforcement authorities recorded more than 900 mass protests in the Ukrainian SSR, which was about 57% (!) of all anti-government protests in the USSR during that time. Bohdan Patryliak counts more than 1,000 revolts in February-March 1930.

- Read also: How Stalin crushed the Euromaidan of 1930

One example is the riots in the Zolochiv district in Kharkiv region in April 1932. On the night of April 15, up to two thousand rebels from the district’s 13 villages сaptured a train depot where grain was being stored. In spite of being fired at by guards, the peasants emptied three wagons filled with grain.

Moreover, the massive withdrawal of Ukrainian peasants from collective farms was dangerous for the authorities. In the first half of 1932, 41,200 farms withdrew from the collective farm system in Ukraine.

Volodymyr Viatrovych, Ukrainian historian and former head of the Institute of national memory, compares 1918 with events going on now in Russo-Ukrainian relations:

What is now called a new kind of war, referring to the hybrid war waged by modern-day Russia, is about the same as in 1918, when some local "authorities" were created in parallel with legitimate power. Kharkiv is declared a "Soviet republic", which asks for "help" from the Bolshevik regime in Russia. The help comes and by the force of bayonets tries to establish itself in the territory of Ukraine.

However, taking into account the Ukrainian national movement, Bolsheviks had to create the Ukrainian SSR and starting a policy of Ukrainization. At the same time, such a compromise could not exist too long. The Ukrainian movement was becoming stronger. Partially liberal Lenin’s New Economic Policy maintained and even facilitated the class of rich Ukrainian peasants who were becoming the driving force for the Ukrainian urbanization of cities. At the same time, the new wave of Ukrainian cultural uprising started, which was later destroyed by Stalin in the 1930s and became a notorious “Executed Renaissance”. Whenever attempts at communist economic policy were conducted in villages, like military communism in 1919-1921 or Stalin’s collectivization after 1929, mass revolts and oscitancy of official Ukrainian communist powers would occur.

Taking all this into account, the Holodomor cannot be explained only by some social reasons, by Stalin’s policy, industrialization and “the need of bread for the cities” which was the case but only on the surface, in the official documents. In the background, Stalin wanted to subjugate Ukrainians, who constituted around 24% of the total Soviet population and, at the same time, the largest poll for peasant’s revolts and second-largest national culture in the Union. Fears of Stalin were explained by himself in his letter to L. Kaganovich from 11 August 1932 where he says that Ukraine is the biggest problem right now, particularly as he is suspicious about the Ukrainian communist party (500,000 people) and openly hostile to Ukrainian peasants.

Such Stalin’s thoughts also correspond with his policy of breaking away with internationalism and promoting Russo-Soviet chauvinism that was particularly well examined in the book of David Brandenberger National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity. Today, while in Ukraine 79% of people consider Holodomor as genocide, in Russia Putin continues the policy of glorification of Stalin.

Ukrainian intellectual Vitaliy Portnikov also compares the establishment of Soviet Ukraine in 1919 with the contemporary conflict and emphasizes that Stalin was an expert in the national question. During the 1930s, his imperial ideology starts appealing to the memory of the Muscovite princes and Russian emperors. And Stalin no longer saw any contradiction between building communism and appealing to the Russian empire, Ivan the Terrible becoming one of his favorite characters.

Having served as the first nationalities commissar in the Soviet government, Stalin could not fail to remember that the Bolsheviks had established control over Ukrainian lands only a decade earlier, after a bloody war. And this was not a civil war as in Russia. This was a war of the Russian Red Army and its henchmen in Ukraine against Ukrainians. If one is to use modern political vocabulary, it was a war against Ukraine with the help of the “Donetsk People’s Republic.” Only then the “Donetsk People’s Republic” won.

"As for the rural kulak in Ukraine, it is much more dangerous to us than the Russian kulak ..." - in 1920 already, one of the Bolshevik leaders Leon Trotsky emphasized. And his words became particularly true during the revolts of 1929-1931. The increase in tension in the Ukrainian village is best illustrated by the increase in the number of acts of terrorism. While 173 terrorist attacks were carried out in 1927 against the representatives of the Soviet authorities and rural assets, in the 11 months of 1928 there were 351, and in 1929 the bodies of the prosecutor’s office recorded 1,437 terrorist acts. One should take into account that “terrorism” in the Soviet Union was not how it is perceived today.

In total, during the 1930s, the prosecutor’s office recorded over 4,000 mass revolts in Ukraine. The number of participants in these actions is estimated at nearly 1.2 million people. Guerrilla units continued to operate in different regions. Some of their leaders in Ukrainian villages were turned into legends. "We, the children, instead of playing hide-and-seek, were entertained by the "bandit Klitka [name of one of the legendary protagonists]," recalled the Ukrainian writer, a native of Lokhvitsa, Mykola Petrenko.

During 1930 and 1931, the prosecutor’s bodies uncovered dozens of clandestine peasant organizations and "groups." It is still not definitively established which of them were real and which were invented by the Chekists themselves. However, one thing remains certain – the Ukrainian peasantry did resist the regime.

The revolt lasted only a few days. Armed with hunting rifles and pitchforks, the rebels began their action on one of the farms and went to nearby villages, recruiting their neighbors. The rebels were supported by some party activists and planned to go to Pavlograd, where, according to the agreement of one of the leaders of the uprising, they had to be supported by the police department. But in the end, those plans failed. To suppress the action, the authorities threw hundreds of better armed and organized security officers. Thirty rebels were shot, two hundred were imprisoned.

Witnesses to those events still live in Ukraine. However, even today some of them are still wary of talking about the revolt. Many of them once denied any ties with relatives participating in the revolt.

As Ukraine discovers more and more facts about the Holodomor and breaks away from the narrative of victimization, the Holodomor Museum in Dnipro will be renamed the "Museum of Holodomor Resistance".

2019 petition to Bundestag – update on the struggle for international recognition as genocide

At the same time, the official international recognition of Holodomor as genocide is slowly developing.

- Read more about the recognition issue at: Holodomor, Genocide & Russia: the great Ukrainian challenge

In the winter and spring of 2019 more than 56,000 people signed a petition to the German Bundestag to recognize the Holodomor as genocide. The Bundestag has yet to finally vote on the petition. However, preliminary remarks by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs show double standards. The Ministry rejects the possibility to apply the UN convention on genocide retroactively in time, although this was done to recognize the Holocaust as genocide. Also, the Foreign Ministry claims that artificial famine was not only in Ukraine but also in some parts of Russia and Kazakhstan. However, it ignores the fact that in those Russian territories mainly ethnic Ukrainians lived at that time, and regarding Kazakhstan, it’s entirely justified to recognize the death of around one million people there as genocide too.

The member of the Bundestag Petition Committee Arnold Faatz considers such logic as from the Foreign Ministry dangerous.

It contradicts the assessment that we rightly give today to the illegal actions of the National Socialist regime in Germany. Indeed, then soon the Nazis will begin to demand that Hitler’s genocide, which also took place before the definition of this concept, was also overestimated accordingly. After all, this also happened before 1951.

Faatz believes

that such a decision by the Foreign Ministry “means kneeling before Russia.” For now, 18 countries have recognized the Holodomor as genocide, including the US in 2018. However, even on the background of the 2014 Russian aggression against Ukraine, the narrative that Russian and Ukrainian are something very close and not antagonists is still well maintained in the discourse, not least because of Russian contemporary propaganda and media efforts. Vitaliy Portnikov comments on this:

The same people who know about the deliberate expulsion by the Stalin regime of the peoples of the Caucasus or the Crimean Tatars — on the basis of their nationality — do not believe that the policy of the Bolshevik Central Committee could be directed specifically against Ukrainians. The first big lie in the perception of Holodomor lies in this unwillingness to see and acknowledge obvious facts.

Read more:

- So how many Ukrainians died in the Holodomor?

- Was Holodomor a genocide? Examining the arguments

- The Holodomor of 1932-33. Why Stalin feared Ukrainians

- New film shows Kazakhs they suffered a Holodomor too, infuriating Moscow

- See which countries recognize Ukraine’s Holodomor famine as genocide on an interactive map

- “Let me take the wife too, when I reach the cemetery she will be dead.” Stories of Holodomor survivors

- How Stalin starved 1930’s rural Ukraine to quash political enemies: Anne Applebaum interview