The Russian government’s efforts to undermine and push out of general use Turkic and Finno-Ugric languages are well-known, but its attempts to destroy Slavic ones in favor of standard Muscovite Russian are less well-known but far more radical and far-reaching, according to Siberian commentator Yaroslav Zolotaryev.

Like its predecessors, the Russian Federation likes to present itself to the world as “the defender of certain ‘Slavic interests’” on the international scene while at the same time within the country continues the destruction of unique Slavic languages of the peoples of Russia and replacing them” with Muscovite Russian, the commentator says.

The Slavic languages of central Russia were long ago declared “’dialects’ of the Moscow standard and destroyed,” he continues; but “up to the present, the languages of Slavic peoples relatively far from Muscovy – the Pomor, the Don and the Siberian – have preserved themselves comparatively well” given the state’s opposition to them and the people who speak them.

Tragically, while all three are spoken by members of the older generation, none is supported by other than “groups of enthusiasts who attempt to create a literary standard” without help and far more often against the active opposition of the Russian state despite its international commitments.

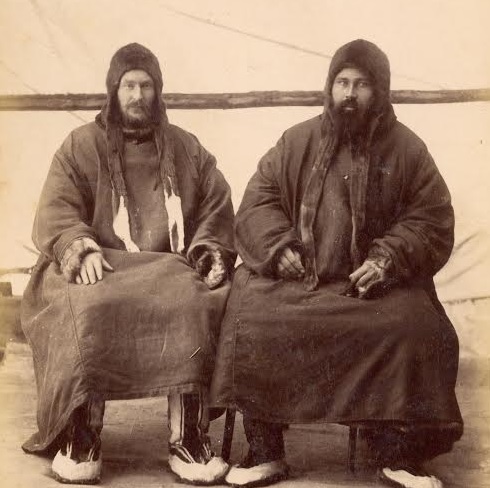

The Pomor dialect is “a representative of Old Russian languages which now is actively seeking recognition as a separate language” spoken by the Pomor people of Arkhangelsk and adjoining areas. Its enthusiasts, Zolotaryev says, are “attempting to codify the language and create a literary tradition.”

Pomor, he continues, “has a distinctive phonetic system and grammar which corresponds to the norms of the Novgorodian language of the middle ages,” a language which is “much more ancient than the Moscow dialect which lay at the basis of the literary norms developed in the 18th century.”

“In fact,” Zolotaryev says, “the Pomor language is the only living heir of this language which now remains. No serious efforts to defend it are being carried out. Parents teach it to their children at home but no books are published in it, no television is broadcast in it, and there are no schools, in short nothing like what minority languages in Europe enjoy.

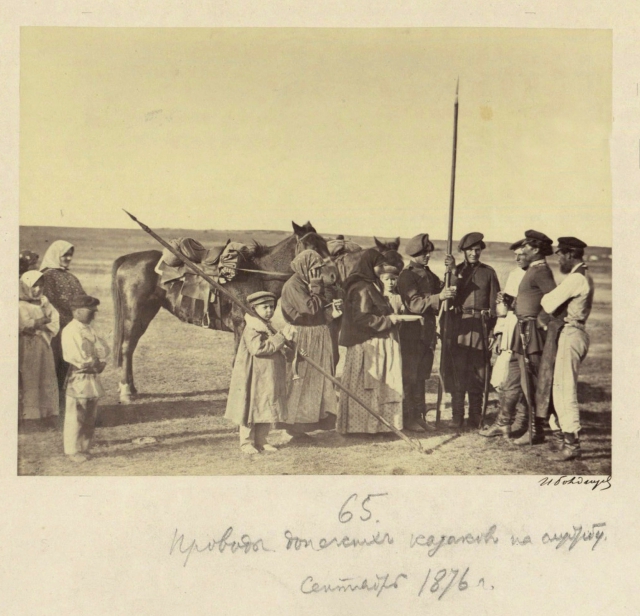

The second of these three Slavic languages is the Don language, the language of the Don Cossacks. Despite de-Cossackization [the Soviet policies to destroy the Cossack people], the language continues to be used; and it enjoys the support of some Cossacks but is actively opposed by the state which insists that the Cossacks are a social stratum of Russians rather than a separate ethnic community.

The Cossack language arose together with the Cossacks in the 17th century, Zolotaryev says. And by 1918, “when the Don received independence, it was declared that the Don language would be one of the state languages of the Cossack Republic. Unfortunately, the Don Republic died in the struggle with communists” and little came of that.

Now, “as in the case with Pomor and Siberian, there is a movement for the rebirth of the language which is conducted on a private basis and does not have any government support.” In Rostov oblast, the Cossacks are told that “they are Russians,” and there is not a single newspaper in Cossack.

And the third of these Slavic languages is Siberian. It emerged among the oldest settlers of the region and took shape in the 17th and 18th centuries, in many ways influenced by Pomor. By the late 19th century, the great Russian lexicographer Vladimir Dal declared that “the language of the Siberians is just as different from Russian as Ukrainian is.”

With collectivization and the forced influx of people to Siberia in Stalin’s times, the Siberian language was in many cases overwhelmed by Russian. But in the first years of this millennium, there was a mass movement which sought to promote its rebirth. Moscow and the FSB worked hard to close down this effort declaring it “extremist.”

Thus, Zolotaryev sums up, “three really distinct Slavic peoples – the Pomors, the Cossacks and the Siberians – are being destroyed in Russia: their languages not only are not being developed but the state often persecutes those who try to do so.”

Read More:

- Broad coalition of non-Russians launch Internet petition drive against Putin’s language policies

- New Siberian website provides data on Russification of non-Russians and repression of Russians

- Why Ukraine’s language law is more relevant than ever

- Should Ukraine take over the Russian language? Scrutinizing Prof. Snyder’s arguments

- Vitaly Portnikov: the Ukrainian language is Putin’s arch-enemy

- Ukraine adopts law expanding scope of Ukrainian language

- Ukrainian writer & publisher: Language is the most important marker of national identity

- Russia’s war against the Ukrainian language

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics

- Professor Michael Moser: Ukrainians should respect their language and culture

- Burning of Ukrainian-language books continues in Crimea

- Terrorists in Luhansk ban study of Ukrainian history and language

- Moscow’s success in gutting Crimea’s independent media and Two meanings of ‘Russianization’

- Warning to Kremlin: Its non-Russians likely to become the Irish of the 21st century

- Moscow deliberately undercounting ethnic Ukrainians in Russia, Kyiv official says

- A real ‘wedge’ issue: Ukrainian regions in the Russian Federation