On 16 July the law "On provision of the functioning of the Ukrainian language as the State language" came into effect, eliciting the reincarnation of many myths and misinterpretations around Russian speakers in Ukraine. This law was an answer to scandalous Kivalov-Kolesnichenko language law which was adopted back in 2012, which granted Russian the status of a “regional language” in a number of regions. A number of oblast and district councils recognized Russian as a regional language: for this, 10% of the population in the region considering Russian (or Romanian and Hungarian in the case of two oblasts), as their native language was sufficient. The law caused much criticism both in Ukraine and in the West.

The Venice Commission considered the law “unbalanced, as its provisions had disproportionately strengthened the position of the Russian language without taking appropriate measures to confirm the role of Ukrainian as the state language and without duly ensuring protection of other regional and minority languages.

This law had not been vetoed by the president until April 2018, when a new law on language policy was adopted. It aimed to strengthen the state language’s role and to regulate its use in education, media, and business without infringing on the sphere of private communication. However, it also reinvigorated myths and horror stories about penalties and punishments for those who speak Russian, which were actively distributed by opposition MPs and Russian media.

Deconstruction of the myths

According to the new law, newspapers and websites in foreign languages will not disappear: they are required to have Ukrainian versions, with exceptions made for products in EU languages and languages of indigenous peoples. Books, newspapers, and magazines will be required to publish no fewer than 50% of their copies in Ukrainian. In the public sphere, the default language will be Ukrainian but people will be able to speak whatever language they like upon the agreement of both parties, so Russian and other languages of minorities are likely to be spoken as freely as before.

Historical background

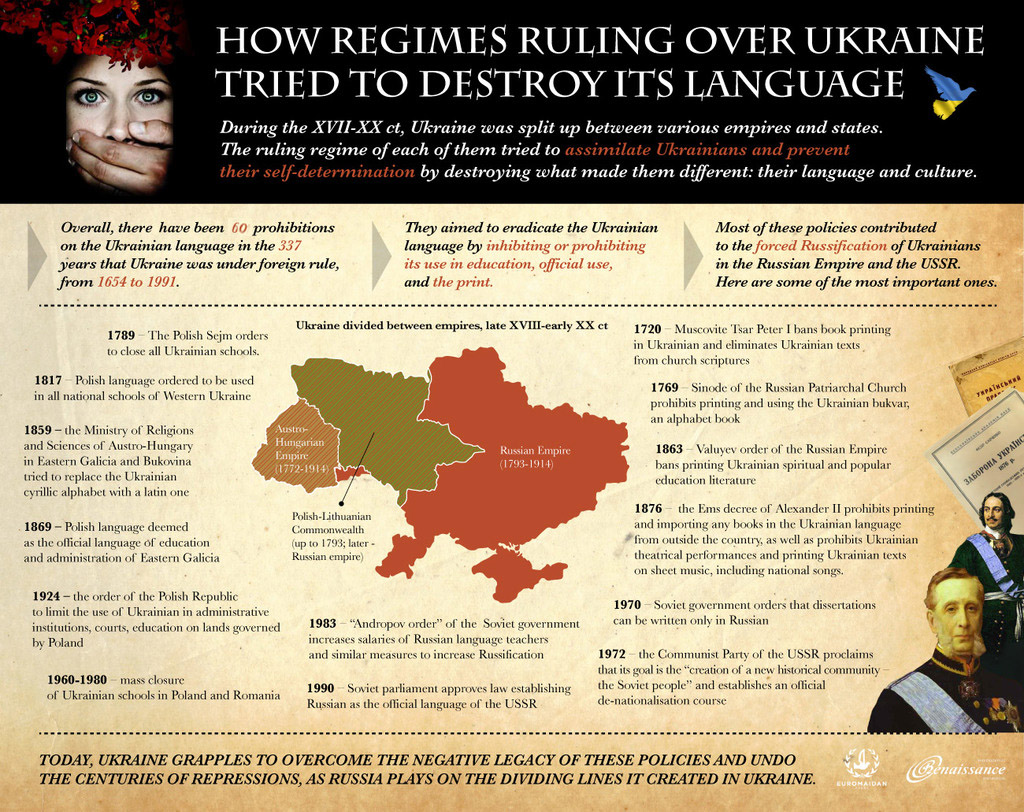

In Ukraine, Russian language and its status are both consequences of the imperialistic and Soviet past. Due to its post-colonial status, the Ukrainian language was pushed to the margins of all areas of life.

In Tsarist Russia, the Ukrainian language suffered from numerous prohibitions. For instance, in 1863 Valuyev Circular, a decree suspending the publication of many religious and educational texts in Ukrainian, or as the Russians called it, Little Russian, denied its existence:

“...a separate Little Russian language has never existed, does not exist and cannot exist, and that their dialect, used by commoners, is just the Russian Language, only corrupted by the influence of Poland; that the common Russian language is as intelligible to the Little Russians as to Great Russians, and even more intelligible than the one now created for them by some Little Russians and especially by Poles, the so-called Ukrainian language. Persons of this circle, who are trying to prove the contrary, are reproached by the majority of Little Russians themselves for separatist plots, hostile to Russia and disastrous for Little Russia.”

This decree was strengthened in 1876, when Tsar Alexander II signed the Ems Ukaz, banning the use of Ukrainian in public sphere: printing and importing literature and sheet music, staging the performances in Ukrainian or including national songs in theatre plays.

The end of the Russian Empire did not mean the end of cultural colonialism: aggressive imperialistic methods were successfully inherited by the Soviet Union. The Ukrainian language had suffered from a so-called “linguicide” presented as globalization aiming to turn Russian into a Soviet variant of lingua franca. The quintessence of Soviet vision of Ukrainian is displayed in Maxim Gorky’s quote about the translation of his novel “Mother” into Ukrainian in 1926:

“It seems to me that translation of this novel into the Ukrainian dialect is also unnecessary. I am very much puzzled by the fact that people who have in front of them the same goal, not only reaffirm the difference between dialects, but also try to make a language out of a dialect and even oppress those Great Russians who have found themselves as a minority in the area of the respective dialect.”

Source: Nashe siohodni, Vaplite, No. 3, 1927, p. 137.

Ironically, even nowadays the funhouse mirror of Russian propaganda still distorts reality with the same primitive methods, triggering a painful déjà vu. This hysteria is most pronounced by odious Russian politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky, having a renommée infused in populist, propagandist and anti-Ukrainian sentiment, who claims that both the Ukrainian language and Ukrainian nation do not exist.

“This so-called Ukrainian language was created by the Austrians, who called the western part of Russian people ‘Ukrainian.’ Now it’s still going on and that is why Donbas is on fire… It’s a burp of the Austro-Hungarian empire,” said Zhirinovsky.

After the times of aggressive Russification, accompanied by the extermination of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, came a period of “soft” linguistic assimilation using another type of weapon - humor. Soviet media created an image of Ukrainians as provincials - naive and not very educated. They were allegorically shown as bizarre peasants speaking some macaronic language - a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian. For instance, a duet of stand-up comedians, Shtepsel and Tarapunka, popular in Soviet times, represented a traditional division of roles: rational and intelligent Shtepsel speaking Russian versus simple-minded thickheaded Tarapunka speaking surzhyk - a chaotic blend of Ukrainian and Russian.

What is even more interesting, this tendency was reflected also in independent Ukraine. For instance, in comical shows by Kvartal 95, at the time headed by Volodymyr Zelenskyy who is now the President of Ukraine, the Ukrainian language was used for mocking and burlesque only. Furthermore, in the TV show Servant of the People, in which Zelenskyy played the main role, it was said that the question of language is used by oligarchs to divide people, distracting their attention from economic problems.

Andriy Bohdan, the Head of the Presidential Administration, has also claimed that Russian should become a regional language in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts if it helps to strike a balance and to stop the war in Donbas.

The Shtepsel and Tarapunka duet was, after all, in some way a metaphor of reality: it was far more prestigious to speak Russian than Ukrainian, especially in the urban space. Moreover, this tendency is still relevant, especially in the eastern and southern parts of Ukraine. This makes the widely-circulated thesis about the language law oppressing the rights of Russian-speakers not very logical.

The permanent simultaneous use of two languages in Ukrainian media caused the phenomenon called “linguistic schizophrenia” - a cultural policy of mixing two languages, which can lead to the gradual displacement of one of them. Therefore, the mission of the language law is to protect the status of the state language giving it the opportunities for development. However, members of opposition parties used the law for manipulations, stating that it divides Ukrainians into two camps.

Russia uses the same rhetorics claiming to “protect” the rights of the Russian-speaking population of Donbas. But actually, without this language law regulating the status of Ukrainian as the only state language, it is rights of Ukrainian-speaking people that are in danger.

The hypocritical speculation on “oppressed Russian-speakers,” nevertheless, has nothing to do with reality and clashes with Soviet politics of aggressive Russification, where Ukrainian words were deleted from dictionaries, and Ukrainian was artificially brought closer to Russian in the linguistic reform of 1933. In fact, Russian is still very widespread in Ukraine, remaining in the position of a Big Brother in such spheres like business, industry, science, and politics. Language is still being used by Russia as a tool of manipulation and power.

The statement that Russian is being banned from the private sphere is ridiculous since the new language law does not ban books, websites, and press in Russian or any other language, but only creates an enabling environment for the state language to flourish using the methods of soft power. Ukraine still has its stigmas and traumatic reputation with its linguistic and national identity having been jeopardized, so the thesis that protection of the state language separating Ukrainian people does not look very logical.

Read also:

- Language bill must be approved to stop aggression against Ukrainian, says writer

- Professor Michael Moser: Ukrainians should respect their language and culture

- Ukraine creates free online courses of Ukrainian language for foreigners

- The Ukrainian language is gaining ground, official says

- Should Ukraine take over the Russian language? Scrutinizing Prof. Snyder’s arguments