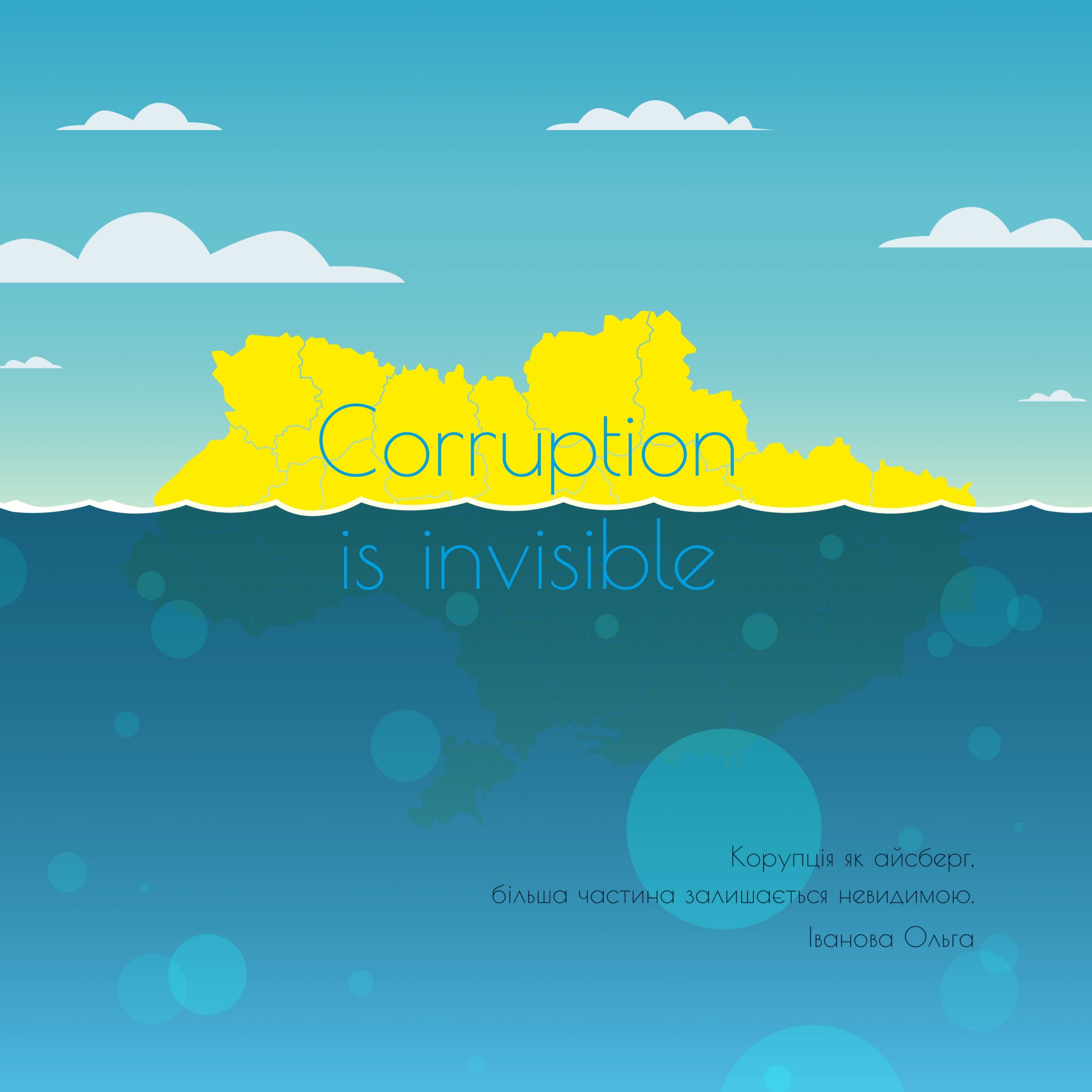

The researchers confirmed that corruption usually gets to the top of the list of Ukraine’s major problems. In their latest survey, it is rated third after high living costs and warfare in eastern Ukraine. However, the researches went further and divided corruption into levels – top-corruption, domestic corruption, and corruption in business. In this case, the last two types of corruption, which people encounter on a daily basis, would be at the bottom of the list.

“If we replace the word ‘corruption’ with ‘political corruption’ we would receive the same third place. So when citizens talk about corruption as a serious problem, first of all they mean top-level political corruption,” says Ivan Presniakov, anti-corruption expert at USAID ENGAGE.

To a large extent, the disproportion in perception might be caused by media coverage. When telling about corruption, media aim at news related to embezzlement committed by top-officials. As the respondents of the study told, the main reason for corruption in Ukraine is the lack of punishment for it and, correspondingly, the most effective measure in fighting it is to punish the top-corrupts and make punishment inevitable. The second popular measure is to deprive MPs of their immunity.

Also, research reveals that 41.5% of respondents confirmed that either they or their family members had encountered corruption over the last year. This indicator has dropped significantly since 2007 – by almost 25%.

“Two-thirds of the respondents justify their involvement in corruption by caring about their safety, comfort, and desire to resolve problems quickly. A quarter of respondents does not take part in corruption due to understanding of harm of corruption for society, desire to live according to the rules, and moral satisfaction from saying ‘no’ to a corrupted person,” says Maksym Kliuchar, Deputy Director of USAID SACCI.

One of the examples of caring about safety are cases when people had to bribe doctors to receive better services.

Presniakov says that talking about the corruption experiences of citizens, one should take a look at which state institutions citizens interact with the most. Healthcare institutions are at the top of the list – 63.8% of respondents used medical services.

“So when we talk about encountering corruption and how it drops over the years, we should understand that to a large extent that changes in experiences in the healthcare system are a driver of change,” says Presniakov.

However, according to the researcher, if we measure not the ratio of encountering corruption among the general population, but the relative ratios of corruption in specific fields, some other leaders in corruption would emerge.

“Higher education leads in providing corruption experiences: six out of ten people who interacted with the sector said that they were requested to give a bribe, proposed a bribe themselves, or used personal contacts in it,” says the expert.

The researchers also observed a huge disbalance between those whom Ukrainians consider responsible for fighting corruption and those wanting to fight corruption. Citizens see the president, Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) and the Cabinet of Ministers as having primary responsibility for curbing corruption, while common citizens, media, and civil society organizations are among those trying to do it.

“What we see as a problem is that in 2018, only 10.6% of respondents think ordinary citizens are responsible for fighting corruption. This is the lowest indicator among the results of the previous 11 years. And compared to 2015, this indicator dropped almost by 13%. Also, we asked whether society can have an influence on decreasing corruption. Most citizens chose so-called passive answers regarding it. The most popular one is that they can’t influence it, and the second popular answer is that they simply shouldn’t give bribes. So some activities are not on the agenda,” says Presniakov.

The researchers identify that the greatest demotivator which prevents citizens from holding an active position is a belief that they can’t change anything, safety concerns, and a threat of financial instability of them and their families.

Among the respondents, 36.4% of citizens said that they are ready to join anti-corruption activities. These activities include participation in Public Councils, protests, informing law enforcement institutions about corruption, support for NGOs etc. 11.5% of the respondents stated they already took part in such activities.

Meanwhile, leading anti-corruption NGOs in Ukraine started working on building the mental bridge between top-corruption and finances of ordinary citizens.

In particular, Transparency International Ukraine, Anti-Corruption Action Centre (AntAC), and CASE Ukraine with the support of USAID launched a campaign to raise awareness of how much money citizens give to the state in the form of taxes.

According to the NGOs, tax payers finance the state treasury the most, and 73% of its revenues come from taxes paid by ordinary citizens.

“There aren’t any ‘free state services’ – all of them are funded from our taxes. In average, a Ukrainian family with two working people gives the state more than $4,000 a year. In large cities – nearly $5,000. It is important to understand the numbers and how they fill the state budget; then, you start thinking as an owner [of the money],” said Vitaliy Shabunin, head of the AntAC.

The AntAC and CASE Ukraine launched the site cost.ua where every citizen can check how many taxes he really pays.