On 28 September 2017, Ukraine's new law on education entered into force. Called to advance Ukraine's badly needed education reform, it has been praised for introducing the concept of competence-orientation and giving schools more independence, as well as increasing teachers' salaries from the average $202 to $370. However, this wasn't the reason for its international fame: in the weeks after its adoption on 5 September, Ukraine has come under attack of its neighbors for Article 7 of the law stipulating that in all Ukrainian schools, Ukrainian will be the language of instruction after Grade 4 (with the exception of schools for Crimean Tatars, an indigenous people of the Crimean peninsula occupied by Russia in 2014, and concessions made for EU languages, in which one or more subjects can be taught after Grade 4):

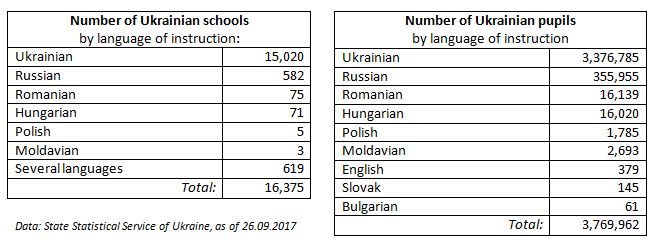

- The foreign ministers of Hungary, Greece, Romania, and Bulgaria have complained to the Council of Europe and OSCE about the violation of the rights of their minorities in Ukraine on 14 September (although the Greeks don't have classes studying in Greek, so the law doesn't even influence them, and there are only 61 students studying in Bulgarian in Ukraine);

- Hungary had taken the most fierce opposition. On 19 September, the Hungarian parliament unanimously adopted a resolution condemning the new Ukrainian law. The Hungarian foreign minister Peter Szijjarto announced on 27 September that Hungary would block all steps related to Ukraine's euro-integration within the European Union and guaranteed that "all this will be painful for Ukraine in future.”

- The Romanian Parliament adopted a resolution expressing its "deep concern" about the law. Romanian president Klaus Iohannis criticised the reforms and canceled a planned visit to Kyiv. After a meeting with Romanian education minister Liviu Marian Pop, his Ukrainian colleague Liliya Hrynevych said on 27 September that the language Article will be "clarified and detailed."

- The Russian Duma called the law "an ethnocide of the Russian people."

As well, on 21 September, the Zakarpattia regional council issued an appeal to President Poroshenko demanding he vetoes the new bill.

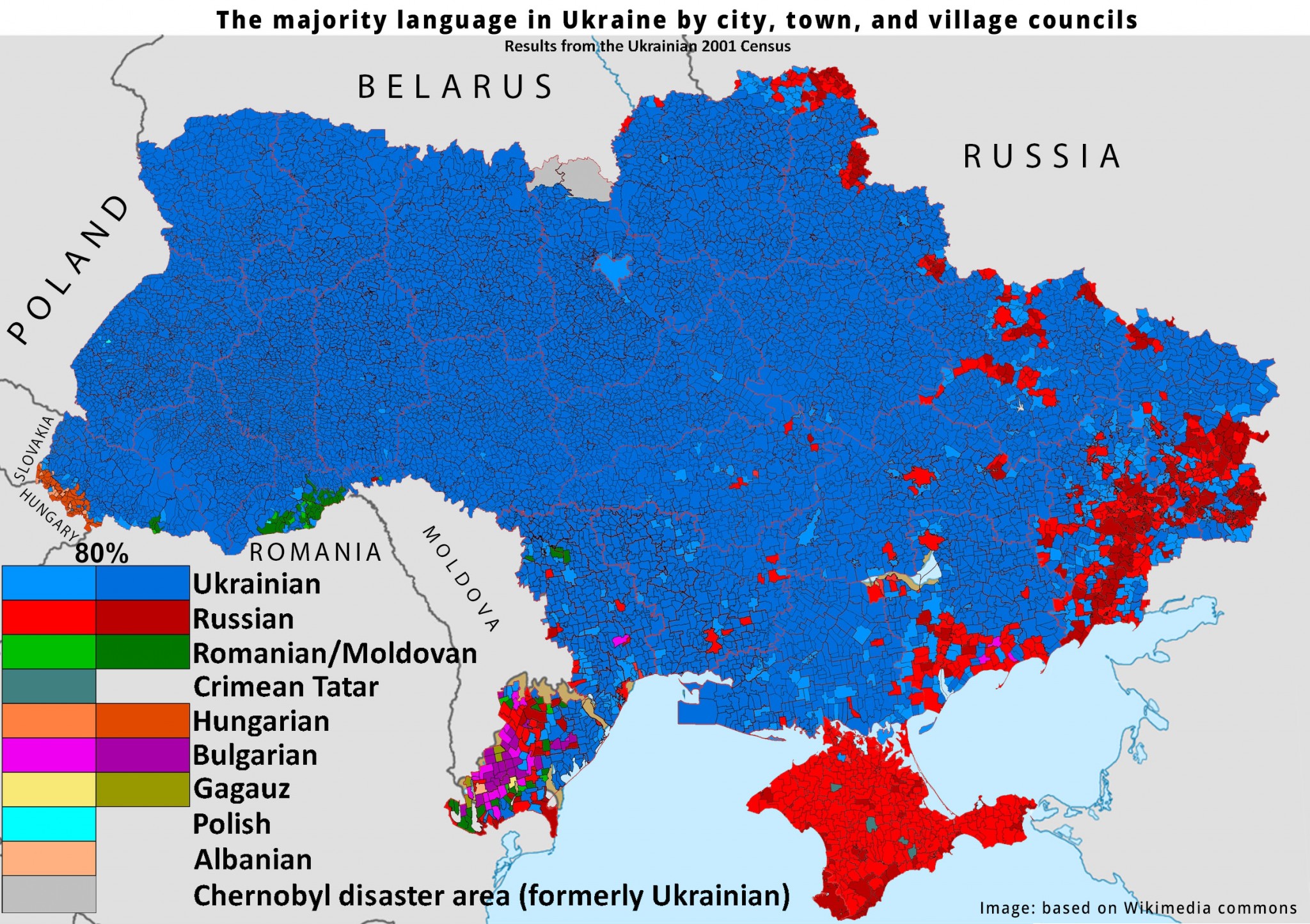

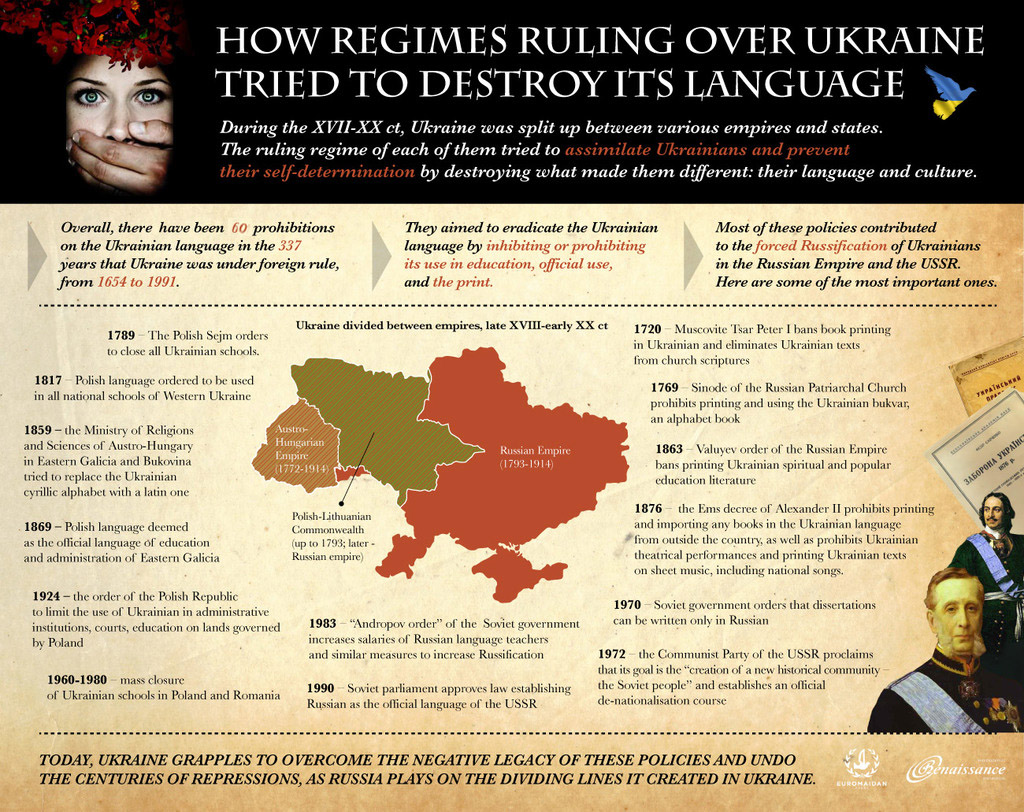

The supporters of the new language provisions cite the need to improve currently dismal levels of Ukrainian ability in some areas with large ethnic minorities, where children can now go through their entire school career being taught mainly in Russian, Hungarian, Romanian, or other languages, which prevents the children from integrating into Ukrainian society, pursuing a university education and job opportunities, as well as breeds isolationism and separatism. As well, these children’s poor grasp of the state language prevents them going on to jobs in national and local administration, and weakens the unity of a 46-million-strong country under huge pressure from Russian aggression, officials say: Ukrainian foreign minister Pavlo Klimkin called it a matter of national security. As a result of centuries of linguicide that Ukraine suffered under different empires, the official state Ukrainian remains de-facto subjugated to Russian till this day.

Does the language Article of the Ukrainian new education law violate Ukraine's international commitments, as Hungary claims? Or is it in line with European practice, like Ukrainian officials say? Euromaidan Press talked with experts in the field to find out.

European approach to ethnic minorities is very diverse

Up till now, ethnic minorities in Ukraine had schools with instruction in their native language, and Ukrainian being studied only as a subject. Roughly 10% of Ukrainian students studied in such schools, with the overwhelming majority of them Russian.

According to Ukraine's education minister Hrynevych, this led to 60.1% of Hungarian and Romanian school graduates flunking their Ukrainian language exam, barring their road to universities.

Hrynevych stressed that the countries criticizing Ukraine have much weaker protections for Ukrainian minorities at home: none of them have schools with the entire education process in Ukrainian. There, students from the Ukrainian national minority has a chance to study Ukrainian only as a subject, or selected subjects in Ukrainian. Everything else is studied in the national language of the country. Thus, Hrynevych concludes, the proposed law is normal European practice.

But experts say it's not so simple. Vyacheslav Likhachev, an expert of the Congress of National Minorities of Ukraine and researcher of the Ukrainian far right, told Euromaidan Press the law doesn't directly violate any European norms, but really such phrasing doesn't make sense because there exist no abstract European norms, and every situation is unique, as is the legislature and education practice. There are countries that haven't undertaken any commitments at all - like France, which hasn't ratified either the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, nor the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages:

"France doesn't have the legal term 'national minority.' In France, everybody is French, irrespective of their religion and ethnic background. The situation is different in other countries. There are countries which provide minority languages an official status, like Finland, where Swedes comprise a minuscule part of the population, but the whole cycle of education, including university education, exists in Swedish, and Swedish has an official status.

As a rule, in Eastern European countries, minority languages don't have this position. For instance, in Romania, there exists one lyceum with education in Ukrainian and that's it. The Romanian government can formally say that it's preserving the Ukrainian language and education opportunities in it for the Ukrainian minority, but this is one education institution where one can study if one is very determined, but in general everybody studies in Romanian-language schools. Hungary, as far as I know, doesn't have any schools with education in Ukrainian, but the Ukrainian minority there isn't large either. Poland has one Lithuanian gymnasium and Lithuania has one Polish one. This is the normal situation for minority languages in Eastern Europe."

Prodded by its neighbors, on 28 September Ukraine had sent the law for assessment to the Venice Commission. Likhachev is convinced that it corresponds to European practice, and doesn't contradict either the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities or the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages:

"Article 8 of the Charter which envisions quite broad and envisions different mechanisms with which the government fulfills its duties to preserve the languages of national minorities in the education sector: it either ensures the availability of preschool, elementary, high school education in the minority languages, or promotes the learning of minority languages. The mechanisms are wide. Generally speaking, if a government abandons education in minority languages but preserves its commitments to facilitate their learning, that means legally Ukraine is not violating any norms and commitments it has undertaken."

Collateral damage of de-Russification

Nevertheless, the Ukrainian situation is specific, Likhachev says. First, Ukraine has many ethnic minorities, they are numerous, and live compactly. For instance, Hungary is home to only several thousand ethnic Ukrainians, while there are 150,000 Hungarians in Ukraine, according to the 2001 census.

Second, the Ukrainification of the language of education was intended to de-Russify the education system and has nothing to do with the Romanian and Hungarians.

"It's apparent that Ukraine's education system needs to be Ukrainified, it's a measure against post-colonial, post-imperial Russophonia. The legislation that existed allowed many more opportunities for using Russian in the education de-facto than there were de-jure: it led to a situation when Russian crowded out Ukrainian or at least prevented receiving a full-fledged education in Ukrainian. In many universities, teaching was often done in Russian, works were accepted in Russian," the expert told.

According to him, the minorities suffered collateral damage from the primary aim of the language section of the law, de-Russification, as the requirements were unified for all languages, and nobody targeted them specifically with Ukrainification. Even though the graduates of Hungarian schools in Zakarpattia do worse in the final tests, and face problems with entering Ukrainian universities, and just speak Ukrainian much worse in general. The problem of insufficient knowledge of Ukrainian by ethnic minorities exists, but dealing with it wasn't the aim of this law.

Children need real multilingualism

According to Yuliya Tyshchenko, an expert of the Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research who participated in projects to implement multilingual education in Crimea before it was annexed by Russia, Ukraine's national minorities need real multilingualism, something that they lack now as they know only their minority language well. For this, parents and teachers need to be worked with, and world practices needs to be studied and taken into account.

"The practice is very different. Italy has a multilingual model of education. In Finland, there is Swedish. In Latvia, there is Polish and Russian. Russian-language children there have possibilities to go to schools that have four different models determined by the education ministry, and those can be varied too. Schools have a right to experiment and self-determination. The gist of multilingual education is to study subjects in the minority language together with the state language. During one year there can be 60% in Russian, 20% in Latvian. The older kids get, the more there is in Latvian, but they still have some options to study in their native language. They do the same for Polish schools, and even have one Ukrainian school. At graduation, Russian-speaking children know Latvian, Russian, English, German at a level to be competetive.

If we take the Finnish experience, they have the Vaasa province where the majority is Swedish-speaking. They have different practices, includng the so-called invasion method. From grade 1, two languages are studied, with very interesting methods. The invasion is basically 'walking' into a different-language environment. There are special methods with which Swedish-speaking kids study Finnish. The majority of subjects are studied in Finnish, but this doesn't contradict the possibilities to use both over the whole process."

Tyshchenko thinks that Ukraine should look for methods of language learning that work, and its problems would be solved, and notes that if Crimea wasn't occupied by Russia, the multilingual education model with studying Crimean Tatar, Ukrainian, and Russian would have started working in some education institutions on the peninsula. When she was working on the Crimean multilingualism project, it were Russophonic parents who signed their kids up for the multilingual kindergarten in Bakhchysarai in 2013-2014. However, the current law is flawed because of its lack of flexibility - each minority has a different historical background and has to be dealt with in a different way:

"In Ukraine, the amendment to the law leaves only one model: to study in the minority language in primary school and further on to have it as a subject while studying in the state language. I think we could have acted more flexibly here. We have good practices in Zakarpattia with the Slovak school, and in the Chernivtsi Oblast with introducing multiligual education. The Hungarians were always against it. The situation with Hungarian schools doesn't encourage multilingualism at all, and the schools are against any sort of experiment, but they need to be worked with. We need to stimulate them so that there would be more Ukrainian there, so the whole process wouldn't be in Hungarian. This doesn't mean the changes have to be radical, I think."

Сommunication problems and Hungarian elections

The leaders of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine took an uncompromising position during discussions on the language policy of the law and lobbied to preserve its status-quo at any cost, civic activist Taras Shamayda, who attended public discussions related to the law, told Euromaidan Press.

Moreover, at a meeting of the Hungarian political parties with socio-political associations of the Carpathian region in the Romanian city of Băile Tușnad in July 2017, Ukrainian MP Vasyl Brenzovych, chairman of the Society of Hungarian Culture of the Zakarpattia Oblast, told of large-scale information campaigns, collection of signatures, and political pressure with which his Society opposed the "anti-Hungarian" policy of the Ukrainian government. Now, Hungary is furious: not only did Foreign Minister Szijjarto threaten to block Ukraine's euro-integration aspirations in the EU, President Orban went as far as to suggest using military force in Ukraine.

Balasz Jarabik, a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment in Washington who lives in Budapest, told Euromaidan Press

these words are mostly meant for domestic consumption: there is an election campaign underway in Hungary. It is unlikely Hungary will find ways to block Ukraine's Association Agreement with the EU, and while Hungary criticized EU sanctions against Russia, it never moved to block them. What irritates Hungary the most is the suddenness with which Article 7 got into the law: right before the final vote, while the reform was prepared inclusively for 1.5 years with consultations, and up to September 5 envisioned minority languages being the languages of instruction in all stages of the education process, the expert told. According to Mykhailo Svystovych, an activist of the civic movement "Vidsich," the decision to change the law was made under pressure from activists who lobbied for a version of the law outlawing education in minority languages altogether and was essentially a result of hyperdemocracy.

Meanwhile, Péter Krekó, Executive director at Hungary's Policial Capital Institute, told Euromaidan Press that this rhetoric is not limited to Ukraine and might not be connected to elections:

"Recently, we had serious diplomatic conflicts with Netherlands (downplaying diplomatic relations), Croatia, Romania (threatening to block their OECD membership), just to mention a few. I think this is the modus operandi of Hungarian diplomacy, when it comes to EU and NATO countries and countries in their sphere of influence such as Ukraine, but not with Russia and some other Eastern countries such as Azerbaijan with whom we are having a friendly relationship. This issue is a symptom of the general radicalization of Hungarian foreign policy and toppling of East-West balance."

Vladyslav Likhachev notes that despite these obvious influence of Hungary on the leaders of the Hungarian minorities in Ukraine, Ukraine's communication failures exacerbated the problem:

"There is a problem with the leaders of the minorities being dependent, money-wise and in other ways, on right-nationalist circles, especially in the Hungarian case. They took an uncompromising position from the very start. But at the local level, the minority communities were not offered explanations on what the existing situation leads to, when minority school graduates de facto don't know the Ukrainian language and they have no other way of integration and professional growth apart from traveling to Hungary and entering university there. The communities basically lose them. Communicating and consulting with representatives of minorities was absolutely crucial, but this was nowhere to be seen. Apart from this, the communities don't understand that, unlike Russian, Hungarian and Romanian are EU languages, and have additional opportunities under the law - they can remain the language of instruction for a limited number of lessons and preserve their place in the education system somewhat. And, as EU languages, they can be used in limited quantities in higher education, which actually expands their role - previously, the language of instruction of all higher education was only Ukrainian.

So the law does give opportunities to preserve minority languages in education and in some spheres even expands it. Communities didn't know any of this, the communities were only outraged that they were being deprived of their native language. The process of communicating was flunked."

Now, the international storm arising from the adoption of the law is perhaps the least of Ukraine's worries, although it did already exacerbate Ukraine's foreign relations: hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian citizens, the loyalty of whom was already problematic already due to a dual identity and the activities of Hungary, are now offended by the Ukrainian state. As well, there could be problems with implementation - the transition period it envisions for the Hungarian and Romanian schools to transition to education in Ukrainian is quite short, the expert tells:

"One or even two years to prepare teachers that formerly taught in a minority language to teach in Ukrainian is insufficient time. I am not sure that the Ukrainian government is ready to undertake the responsibility of preparing teachers for this, as well as programs, learning materials for teaching the minority languages as subjects and not the language of instruction, so they would not forget their language and at the same time be competitive in the Ukrainian-language environment. Theoretically, we can proclaim that the knowledge of the state language for all minorities is, first, obligatory since they are Ukrainian citizens, and second, gives them equal opportunities in Ukrainian life which they were deprived of until now. But how it will be implemented in practice in the case when the innovations will be resisted by both parents and children we will see only in practice."

Meager protection of the rights of Ukrainians to their language abroad

Ukraine's strong protection of the language of its minorities inside the country, to the state of their inability to speak the state language, stands in contrast to the situation with the protection of Ukrainian by its neighbors, embittering Ukrainians against any international remarks about their internal language policies.

In Russia, where there are 1.93 mn ethnic Ukrainians officially, and 10 mn unofficially, there is not a single school with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, and Ukrainian is studied as a separate language in several schools in Ufa, Vorkuta, Krasnodar, Murmansk, and Penza, along with several Sunday schools across the whole country, the Head of the International Ukrainian Coordinating Council Mykhailo Ratushnyi told DW. The meager protection of Ukrainians inside Russia has been a stumbling block between the countries far before the war in Donbas. Russia cited the low demand from Ukrainian parents, but Ratushnyi says that the Russian authorities ignored the needs of the Ukrainian minority and intimidated activists by visits from the FSB.

As of 2011, 51,000 ethnic Ukrainians, for 49,000 of whom Ukrainian is the native language, lived in Romania, where the authorities took upon themselves the obligation to provide education to the ethnic minorities without the request of parents. This is 10,000 less

than in 2001. But today elementary and 8-year schools with Ukrainian being the language of instruction are absent in Romania. The only comprehensive Ukrainian educational institution is the Taras Shevchenko Pedagogical Lyceum in the city in Sighetu Marmaţiei, which is flaunted off by the Romanian authorities at every bilateral and international meeting. Nevertheless, a Ukrainian diplomat who worked in Bucharest a few years ago told DW that the number of its students is falling and the local Romanian authorities are engaged in a hidden agitation campaign to discourage their children from studying in Ukrainian. But the largest assimilation of Ukrainians already happened in the 1960s, when Ceausescu's regime closed down all the Ukrainian schools.

8,000 Ukrainians live in Hungary, where Ukrainian is recognized as a minority language. However, there are no schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction in the country. The authorities explain this by a lack of demand from the Ukrainian community.

The practices and conditions for minorities in Ukraine and the neighboring countries should be studied systematically and a dialogue should be held, Yuliya Tyshchenko told Euromaidan Press. Regarding minorities in Ukraine and Romania, 10-15 years ago, a mutual monitoring about the rights of both was conducted. There was also a monitoring conducted with Russia, which revealed that indeed the conditions for studying Ukrainian there are very bad, the expert said.

The Head of the International Ukrainian Coordinating Council Mykhailo Ratushnyi told DW that the Ukrainian government should protect the interests of Ukrainians abroad more actively. Now, there is no Ukrainian state program to work with the diaspora like the ones Poland, Russia, Romania, Hungary and other countries have. He suggests that a separate state organ would improve the situation.

Reverse sequence of events

Ukraine is making changes to its education law to overcome the centuries of Russification which were directed at assimilating the Ukrainian nation by destroying its language. Paradoxically, the legislation determining Ukraine's language policies today had been adopted in the USSR, Vyacheslav Likhachev told Euromaidan Press - the absence of a consensus and clear view of what the state language policy has to be led to a situation in limbo which is starting to be justified now, but with a wrong sequence of events:

"We cannot build a house starting from the roof. We need to build it starting from the foundation. To identify the foundational questions of Ethnopolitics, the Ukrainian state has to understand what it is from the viewpoint of Ethnopolitics. Is it a unified state where all the people are Ukrainians at the level it is in France, where there is no education in minority languages, and no schools for indigenous people? Or does it envision a broad national-cultural autonomy for ethnic groups, like other countries? I think that Ukraine has to define these things for herself, and adopt basic, framework documents, a state concept of ethnic politics and laws on national and cultural autonomy which would create a legal basis for national culture, education, media without creating conditions for territorial claims. The idea of a national-cultural autonomy was once conceived in such a manner, to allow national minorities to realize their rights without creating national-territorial autonomies. For Ukraine this is a very important thing, considering the situation with the occupation of Crimea. These projects are ready, are being discussed. And Ukraine must adopt a law on language.

In this context, 'from this date we start to Ukrainize all the school education' looks like voluntary arbitrariness. Perhaps what's more important isn't how this is perceived abroad, although this matters for Ukraine at the international stage, but how this all is perceived by Ukrainian citizens belonging to ethnic minorities. And they perceived this as a violation of their rights, because previously the Ukrainian legislation gave very wide possibilities for education in minority languages. But this is a consequence of the government not working systematically in this direction, and not understanding conceptually what kind of government it is building. This is one of the chief tasks which the government should undertake on the legal level."

Nevertheless, the expert says that Ukraine can't roll back its decision and must aim to minimize the negative consequences by making colossal efforts to communicate and implement the tasks outlined in the law in the necessary terms, and use the possibilities outlined in the law to teach what could be taught in the minority languages, and, most importantly, teach the languages themselves so that they will not be lost by representatives of the minorities, as well as to inform about the minorities and the international community about the additional options which Hungarian and Romanian enjoy as EU languages.

Read also:

- Ukraine’s new education law unleashes international storm over minority language status

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics