Since 2014, propaganda in the Russian-occupied territories of East Ukraine has been trying to ensure the obedience of the local population as hard as it can. Children and the young people are particularly targeted, not least as the potential soldiers of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine. Ideologists in the proxy “republics” controlled by the Kremlin overdose their minds with so-called “patriotism,” aiming to mutually alienate Ukrainian citizens living on the two sides of the frontline.

But what is the object of this self-made “patriotism”? Is it Russia, which sends its militants to East Ukraine but refuses to incorporate the areas they seized into itself? Or Donbas, two-thirds of which remain under the control of the Ukrainian government? Or the so-called “DNR/LNR,” not recognized by anyone in the world, including Moscow?

It appears that the occupiers are not able to decide on this.

“What’s the name of your Homeland?”

At the end of March 2014, Russian war journalist Viktoria Ivleva came to Donetsk Oblast in East Ukraine, hoping to grasp the concerns of local residents in the time of tectonic political shifts occurring around them. It was a month after former President Yanukovych, who had used to see the Donbas region as his stronghold, fled from Ukraine to the Russian Federation. The power had changed in Kyiv following the victory of Euromaidan revolution, and Russia had occupied and annexed Crimea. Violent clashes were taking place in Donetsk and other East Ukrainian cities but the confrontation had still not reached an open military phase.

While the future of Donbas seemed unclear for everyone, the people whom Ivleva met those days manifested a strikingly broad palette of civic identities. A male resident of Donetsk, who identified himself as a “Russian-speaking Ukrainian,” confessed that the sense of Ukraine as his homeland had been dormant in him until recently but awoke under the influence of the Kremlin’s aggressive policy. However, he could not profess his commitment to Ukraine without a risk to his life unless he was at home, “covered with a pillow.”

Another interlocutor, a young Stalin admirer, sympathetically recalled the allegation of his schoolteacher that “forced Ukrainization was underway but we Russians [russkie] must remember our origins and not succumb.” In Donetsk, Ivleva also attended a rally held under the slogans of combating “fascism,” unification with Russia, and the “referendum on the self-determination” of Donbas. “Russia is my Motherland!”, one female speaker emphatically declared during the rally; her words were acclaimed by the public.

To make things even more complicated, the psychological alienation from Ukraine was not always tantamount to one’s self-identification with Russia. A metallurgist from the industrial city of Makiyivka (close to Donetsk) told Ivleva he would not object if Russia seized Donbas much like it had done to Crimea. “This is not my country,” he said about Ukraine. Surprisingly, however, when the journalist asked him where was his country, he responded: “Nowhere. There is no country that’s mine.”

Soon after this conversation, on 7 April 2014, pro-Russian forces in Donetsk announced the creation of the so-called “people’s republic” (“DNR”). Luhansk separatists followed them with the “LNR” in three weeks.

Russia’s hybrid forces invaded East Ukraine and ensured the affirmative results of the bogus “referendums” on the “DNR” and “LNR” self-determination in May 2014. But the Kremlin leaders did not do what the man from Makiyivka mentioned: the areas of Donbas beyond Ukraine’s control were not annexed to Russia.

In result, the ideologists of the new “republics” had to deal with the vacuum in the mindsets of the people that they declared their “citizens.” If the separatists had previously benefited from this vacuum, now they urgently needed to fill it. A school textbook on Donbas history for kids aged ten to eleven published in Russian-occupied Donetsk in 2015 contained a quote from Ivan Ilyin, Vladimir Putin’s favorite philosopher: “People without a Homeland become the dust of history, faded autumn leafage driven from place to place and dragged by foreigners through the mud.”

In the time of war, “DNR/LNR” education bureaucracy got preoccupied with the questions that echoed those that Victoria Ivleva asked in March 2014:

- What is the name of the country you live in?

- What’s the name of your Homeland?

- My large Homeland is...

- If you were asked to select a country you want to live in, which one would you chose? Why?

These are the questions recommended in 2015 for a primary school children’s survey in the “DNR”-controlled territory. It is unclear whether such a survey indeed took place and if it did, what were the outcomes. We can trace, however, the basic measures made by the occupation authorities to make the answers to such kind of questions politically desirable… and the mess these measures actually cause.

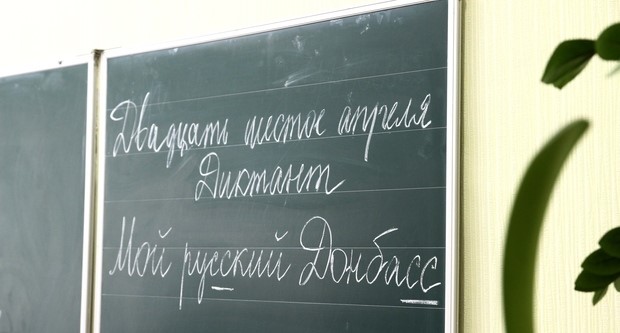

Cutting out Ukrainian language, purging Ukrainian history

In October 2014, the “DNR education ministry” defined Russian as the language of teaching and learning in all the schools and universities it could reach. A year later, textbooks specially brought from Russia substituted the majority of the Ukrainian ones used in the curriculum. For the ones which were impossible to replace, self-proclaimed “LNR leader” Igor Plotnitsky ordered all the mentions of Ukrainian state symbols be removed at the start of the 2016/17 academic year. Following this, first-graders were instructed to tear out the pages featuring the Ukrainian flag and anthem from the books.Authorities in Donetsk literally called teachers to trash Ukrainian history textbooks.

Autumn-2014 also witnessed the abolition of the school subject of Ukrainian history. Luhansk puppet officials announced that they “got rid” of this course because it was “spoiled by [Ukrainian] nationalists.” The new authorities in Donetsk literally called teachers to trash Ukrainian history textbooks. They boasted about their intention to end the “politicization of the past”—implying that impartiality meant the rejection of Ukrainian narratives.

The top priority was to silence the interpretations of the 1932—33 Holodomor Famine in Soviet Ukraine as a planned Stalinist genocide and the history of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army as a chapter in the history of Ukraine’s national liberation struggle. Self-styled “DNR education minister” Larisa Polyakova even labeled the use of the term “German-Soviet War” instead of the official Soviet-time “Great Patriotic War” in relation to 1941—45 a manifestation of Ukrainian nationalism, which, she claimed, “verged on Nazism.”

Read also: Holodomor: Stalin's genocidal famine of 1932—1933 | Infographic

Once the history of Ukraine disappeared from the school timetables, Donbas separatists found that not only “nationalists” but also the Bolsheviks who had promoted the Ukrainian language in the 1920s were to be revenged. A new textbook introduced under the “DNR” claims that Donbas was attached to Soviet Ukraine without the consent of “the people” (as if the Bolsheviks acted differently in other cases). Linguistic Ukrainization of the Soviet public life, reads the textbook, run against the passive resistance of the entire population of the region and was allegedly possible only through intimidation and repression.

In other words, the Ukrainian language and culture are represented as historically “alien” and “useless” for the local population. Their diffusion is depicted as a threat to “our” Russian culture, and this serves as an excuse for an aggressive “self-defense.”

“Russian World” for kids: studying taiga

Cleansing of the education from anything that looks essentially Ukrainian means, to a large extent, an exercise in its cultural colonization by Russia. “We see ourselves as a part of the Russian World,” states “education minister” Polyakova, “and all the people who remained in Donbas in 2014 are Russians [russkie].” Schoolchildren are taught to think of Donbas as a “Russian land” since the unclarified beginnings of its history.The course of “civic education” implies the “Russian World idea” to be taught—without saying what this mysterious thing actually means.

The course of “civic education” introduced in every school under the “DNR” contains a large category entitled “Donbas and the Russian World.” The category includes the overview of Russian history (or, more precisely, the topics ascribed to Russian history) and its personages, from epic heroes to “great emperors.” It implies the study of Russia’s state symbols and her place on the world map, as well as looking into the selected pieces of Russian art, folklore, and traditions such as the manufacturing of matryoshkas (Russian nesting dolls) and bell industry. The course program also mentions the “Russian World idea” to be taught—without saying what this mysterious thing actually means.

The official school program of “civic education” suggests a list of literature in order to gain a supposedly better understanding of the children’s homeland. This indicative list consists exclusively of the books of Moscow publishers and articles in Moscow journals, released both before and after the collapse of the USSR. The typical titles are Our Soviet Motherland, “‘I Am a Citizen of Russia’ Project,” and Russia Is My Motherland.

At the same time, the glossary attached to the program defines homeland (Rodina) as a “citizen’s birthplace.” A person, it reads, “spends her childhood in this place. This can be a country, city, village, or settlement.”

The “civic education” course also aims to teach the models of behavior generalized to ethnic stereotypes. The topic “Russians don’t surrender!” is designed to familiarize children with the so-called traits of the “Russian character” like endurance and selflessness so that they wanted to follow the example of Russian soldiers. Children should be driven to a nationalist conclusion: that the “Russian character” is unique and allegedly determines the peculiarities of Russian history.

The joint “parliamentary” newspaper of Donbas separatists once explained what is the advantage of this uniqueness:

“You can be poor but have a strong military spirit [like Russians] and vice versa: live prosperously but not know what side guns fire from, how to throw hand grenades, and how to assemble and disassemble a Kalashnikov rifle.”

In practice, the massive reorientation of teaching towards Russia is a real challenge for school students. Sometimes it causes comical situations like the one described by a Donetsk resident:

“My son came home and asked: ‘We’re studying what taiga is. [Known also as ‘snow forest,’ taiga is the most common biome in Russia.] And where do we have taiga?’ I had to explain an 8-year-old schoolchild that we live in another country.”

“Non-Russia”: forging local patriotisms

The taiga incident reveals the weak spots of “civic education” in occupied Donbas.

The category “Donbas and the Russian World” occupies one-third of the “civic education” course. The other two parts are entitled “Donbas is my native land”(or “Donbas is my Homeland”) and “Educate in yourself a citizen of the Donetsk People’s Republic.” Technically, all three categories are equivalent. One cannot infer that any of them is deliberately prioritized.

The course program solemnly proclaims:

“The Donetsk People’s Republic aspires to the future when it will constitute not only a single state but also a united nation [yedinyi narod] bound by common values, spiritual senses, and commonness of historical destiny.”

To put this another way, the document favors the emergence of a new community different from those living in the Russian Federation or “LNR”-seized territory. Moreover, “DNR”’s “Conception of the Patriotic Education of Children and Studying Youth” and its “state educational standards” refer to “our nation” [nash narod], or the “nation of the Donetsk People’s Republic,” as if it were not even a dream but an existing fact.

In February 2016, the questions “Who are we?” and “How the young should identify themselves?” were discussed at the round table in the unlicensed “Luhansk University” (the legitimate university institutions work now in evacuation in the Ukraine-controlled town of Starobilsk). Speakers admitted the rising feeling of uncertainty and anxiety among the residents of “LNR”-ruled areas. The head of the Department of Pre-University Training stressed that these conditions compel to inculcate in Luhansk youngsters the idea of belonging to a “self-sufficient ethnos,” which is nonetheless a part of the “Russian civilization.”Each fake “people’s republic” declares itself (rather than Russia) a Fatherland/Motherland and “our country” for the people living within its zone of reach.

Read also: Displaced universities: 18 Ukrainian colleges are exiled in their own country

Each fake “people’s republic” declares itself (rather than Russia) a Fatherland/Motherland and “our country” for the people living within its zone of reach. Such a discourse is unimaginable in annexed Crimea where Russia was declared the only fatherland once and forever. On the contrary, the educational documents and even the anthems of the Donbas “republics” use this particularist wording extensively. Although this strategy is obviously inappropriate from the semantic point of view (given that there are neither fathers nor mothers nor a single schoolchild born under the “LNR” or “DNR”), it underpins the ideas of “military duty” and self-sacrifice in the war against Ukraine.

The ideological workers in occupied Donbas find it hard to clarify what is the correlation of such concepts as “native land,” “region,” and “country,” how far “large” and “minor” homelands reach, and what is the extent of “general,” “regional,” and “local” patriotisms. The new name of the Donetsk Republican Regional Museum incarnates this chaos, as is the topic “Native land: A part of the large country” copypasted from a Russian school program to a “DNR” one.

Ironically, the de facto authorities in Donetsk authorized for using the newest Moscow-published textbooks that contain maps without a trace of either “DNR” or “LNR.” The maps show the whole Donbas as a Ukrainian territory, while annexed Crimea is presented as a “federal subject” of Russia. In this context, a question in another textbook also delivered by Putin’s “humanitarian convoy” to Donbas sounds like unintentional trolling of the separatists:

“Which map can you find and show you land [krai] on:

- Political & administrative map of Russia

- World physical map

- Political map of foreign Europe.”

Only the “A” answer is considered correct by the authors...

Boomerang principle

But this obsession with “unnatural” nations is the very reason why the attempt to draft a new identity in Donbas frightens some of ardent “Russian World” advocates. In the fall of 2014, one of them, Moscow historian Andrey Marchukov, expressed his deep anxiety about the so-called Novorossiya project triggered as a guise of the Russian hybrid war in Ukraine. While this project could become a temporary ally in the anti-Ukrainian fight, Marchukov contended, strategically it would only harm the interests of Russia. In his completely Ukrainophobic article (written, significantly, within the framework of the fundamental research program of the Russian Academy of Sciences), he warned:The weakness of today’s Russia consists in the hypertrophy of her symbolical agenda. This symbolical superstructure threatens to turn against her.

“Suppose that at first everything will be as conceived: ‘Novorossiya’ identity will be constructed as a local variant of the all-Russian identity. But then the question arises of how to put it into practice. The regional specificity will be maximized: otherwise, what is the point of an ‘extra’-identity when there is a Russian one? So it can eventually turn from regional to self-sufficient. A subidentity can acquire the chief role, pushing the all-Russian one to the periphery of consciousness. [...]

‘Novorussianness’ is a complete fancy: there is no separate and clearly designated ethnos, from which the formation of a national collective (even as a subidentity) is presumed. There is no its own history as the history of this and only this region: its milestones, events, and heroes; after all, they are either aliens (those who belong to the “steppe history”) or the common ones, Russian and Russian-Soviet.”

In January 2015, ex-“prime minister of DNR” Aleksandr Borodai admitted that his and his accomplices’ dream about “Novorossiya” remained on paper. Meanwhile, the cultivation of “republican” loyalties in the wreckage of that dream—the “DNR” and LNR”—has been, to a large extent, an improvisation. The self-styled authorities are concerned about slowing down the outflow of young people (potential taxpayers, workforce, soldiers, and voters) to other regions of Ukraine—and Russia too.

Sometimes the education bureaucrats in occupied Donbas employ all possible means, from persuasion to intimidation, to make the parents keep raising and educating their children in the territory where there is neither peace nor law. One can expect the further propaganda of “uniqueness” and “virtues” of quasi-“republics,” which would distinguish their residents from both Ukrainian and Russian neighbors. Significantly, by mid-2016, as much as 31% respondents said they were different from the residents of other Ukrainian regions and the Russian Federation.

In view of this, the thesis on “artificial” identity, which long was an asset of Russian imperial rhetorics, may work as a boomerang able to suddenly hit those who launched it. Back in September 2013, when the Kremlin, trying to obstruct Ukraine from signing the Association Agreement with the EU, started a trade war against her, Ukrainian journalist Pavlo Kazarin emphasized that the opponent was not as invincible as it pretended to be:

“The weakness of today’s Russia consists exactly in the hypertrophy of her symbolical agenda. [...] Russia substituted superstructure for basis. And now this symbolical superstructure threatens to turn against her.”

This conclusion seems particularly noteworthy when it comes to the attempts at children’s ubiquitous indoctrination—both in occupied Donbas and Russia herself.