A Ukrainian bill that would make it easier for congregations to shift from the Moscow patriarchate to the Kyiv one, the Kremlin’s decision to sacrifice Patriarch Kirill’s contacts with the Vatican, and new data on the shifting balance of religious groups in Russia are all religious developments with more than religious implications.

New laws in Ukraine to give more rights to individual congregations

First of all, Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada yesterday took up two amendments to the law on freedom of conscience and religious organizations which if approved are likely to trigger new conflicts with Moscow even as they make it easier for Ukrainian congregations to shift from subordination to the Moscow Patriarchate to that of the Ukrainian one.

Not only do the amendments re-assert the right of congregations to make these decisions on their own without interference from the hierarchies, but they also define those congregations not in terms of the membership claimed by the leadership but by the actual active participants in religious life.

Given that many of the parishes, especially those subordinate to the Moscow Patriarchate claim as members all ethnic Russians in their area, regardless of whether they ever go to church or not, that sets the stage for meetings by active congregants that are likely to vote for a change in subordination.

If that occurs on a massive scale, the Moscow Patriarchate could quickly lose its dominant position in Ukraine among the Orthodox, something that Russian churchmen and officials fear and that commentator Petr Likhomanov argues in Rossiiskaya gazeta shows that Kyiv, having failed to win autocephaly will now use "raider" methods to take control of religious life in Ukraine.

He suggests this could turn the struggle between the two denominations of Orthodoxy from a cold war into a hot one and notes that among those speaking against the amendments were the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, the Apostolic Nuncio in Ukraine (which supposedly fears this tactic will be used against the Uniates), and the Lutherans.

Moscow Patriarchy isolating itself from the West

Second, several days ago, Metropolitan Illarion of Volokolamsk who heads the Moscow Patriarchate’s foreign affairs department, while in Italy, denounced a statement by a Uniate leader against the Moscow Patriarchate, declaring that such comments “sow distrust between the Orthodox and the Catholics.”

Illarion’s remarks, which clearly had the approval of Patriarch Kirill and his backers in the Kremlin, suggest that Moscow has decided to reignite its campaign against Uniatism and thus shoot down all the progress toward cooperation between the Moscow Patriarchate and the Vatican achieved in Havana, when Kirill and Pope Francis met.

That is the conclusion of Kyiv commentator Kateryna Shchetkina who says that this reflects the Kremlin’s decision to isolate Russia from the West and in fact to put up a new “iron curtain” that all of its subordinates, including the Moscow Patriarchate, will have to obey.

Kirill, of course, she notes, was anything but happy about Putin’s seizure of Crimea because it opened the way for Moscow to lose control over the Russian church in Ukraine. Now, he has even more reason to be unhappy because the progress he made in developing contacts with the Vatican has been blocked as well.

That opens the way for a further loss of influence by the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine, Shchetkina suggests, and in turn means that the Kremlin has decided to support elements in Russian Orthodoxy who are opposed to any modernization of church policy or contacts with the West.

Changing balance between religious communities in Russia reflects policies of favoritism and persecution by government

And third, on Monday, at a press conference devoted to the release of new maps on the bishoprics of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Russian Federation, speakers stressed the changing balance of the official entities of religious life in that country over the last five years.

Archmandrite Savva, deputy head of the administration department of the Moscow Patriarchate, noted that in 2009, there was approximately one bishopric for each of Russia’s federal subjects but that now there are 181, with many regions having more than one bishop. He added that this process of administrative growth was close to completion.

Roman Silantyev, head of the Center for the Geography of Religions

in the Patriarchate, said that over the same period, the Russian church had built or restored “more than 5,000 churches in which services are held “not less than once a month, including about 3,700 where they are held once a week or more often.”

Silantyev added that as a result of this growth, “at present, the share of Orthodox organizations among all registered ones has reached 60 percent and is continuing to grow. Fifteen years ago,” he continued, the Russian Orthodox Church had “fewer than half” of all such “legal” entities.

Over the same period, he said, some other faiths have also experienced growth in the number of registered religious facilities, including the Old Believers, the Buddhists, the Muslims, and supporters of the Armenian Apostolic Church. But others have seen the number of their facilities decline.

The largest of those suffering declines in number of facilities since 2009 are “pseudo-Orthodox sects” (down 40 percent), the New Apostolic Church (down 25 percent), and the Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Baptists (all down five percent). Silantyev didn’t say so but most of these declines reflect Russian government repression.

Related:

- Assassination attempts, Russian court orders against Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Kyiv Patriarchate) in Moscow

- Religious persecution continues in occupied Donbas

- Statement of heads of Evangelical Protestant Churches of Ukraine on religious persecution in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts

- Scholar: Russian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate supports repressions, militarism

- Chaplin, ‘a Zhirinovsky from the Orthodox Church,’ says mass repressions necessary and reasonable

- Authorities ready to demolish only Ukrainian church in Russia

- How Russia used Orthodox fundamentalism to hijack the Church Council in Crete

- How the Moscow Patriarchate is creating a separatist Lavra “Republic” in Kyiv

- Pro-Russia militants in occupied east Ukraine torture Protestant pastor to convert to Russian Orthodox Church

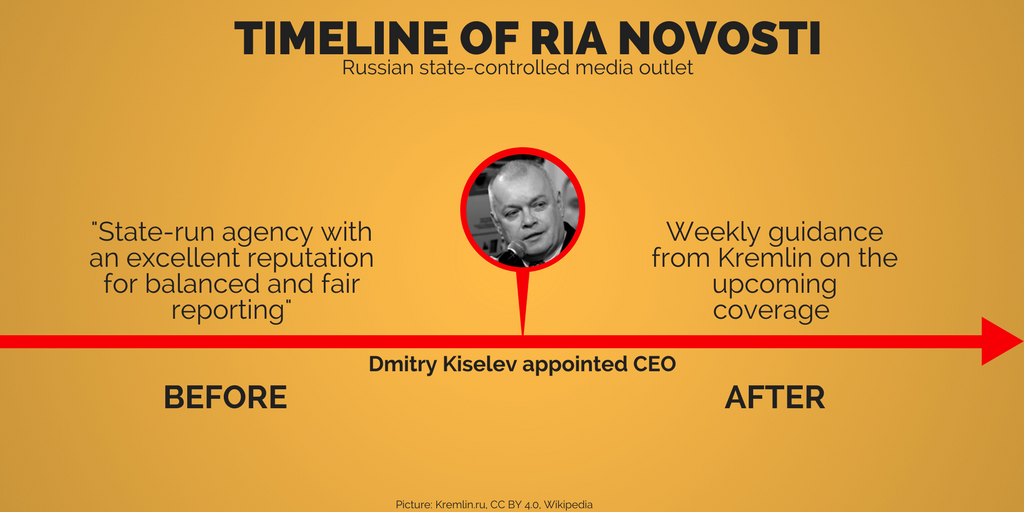

- The Kremlin turns priests into obedient “comrades”

- The Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate resembles the CPSU of Soviet times

- Moscow Patriarchate beefs up its staff for hybrid operations against Ukraine