This is Part 3 in a series. Prior articles:

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 1

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 2. Stories of Ukrainians in the Red Army

On May 22 Volodymyr Katriuk, a Ukrainian World War II veteran and a suspected participant in the massacre of the 186 inhabitants of the Belarusian village of Khatyn [1] passed away in Canada. For years his name had been at the center of a diplomatic row between Russia and Canada over Russian plans to extradite him to Moscow in order to stand trial for his role in the massacre. In 1999 a Canadian court had cleared Katriuk of war crimes, finding him guilty only of falsifying his name in 1951 to obtain Canadian citizenship. Later in 2008 NKVD documents surfaced further indicting Katriuk of having been complicit in the massacre. At the time of his death he remained no.2 on the Simon Wiesenthal Center's "List of Most Wanted Nazi War Criminals."

Just a reminder: Nazi collaborator Vladimir Katriuk (killed innocent ppl in Khatyn in 1943) still lives in Quebec https://t.co/Ciu5R69ud2

— Russia in Canada (@RussianEmbassyC) May 6, 2015

It sometimes happens that Westerners know little about Ukrainians and Lithuanians except their reputation as anti-Semites and willing collaborators in the Holocaust

By no means is Katriuk the only Ukrainian accused of collaborating with the Germans during WWII. Following Stalin's decisive collaboration with Hitler in forming their deadly Nazi-Soviet Alliance in 1939, Ukrainians also participated in the Soviet mode of collaboration. On 17 September 1939 the USSR invaded and annexed Eastern Poland into the "Soviet sphere of influence" under the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. During this period of alliance and cooperation between Hitler and Stalin, a series of meetings and conferences between representatives of the USSR and Nazi Germany were held to discuss how to deal with their common enemies. The best known of these meetings were the Gestapo-NKVD Conferences. In one such meeting on 29 April 1940, representatives of the Ukrainian SSR met with Alfred Schwinner from the German consulate. The “Jewish question” was on the agenda:

![Still from the movie “The Soviet story” showing an excerpt from a German archival document which in part reads “The Soviet representatives started with discussion of the Jewish question. The Germans expressed their point of view that Jews are not a nationality to them, and they disagree that it was a question of race and religion, however [The USSR] acknowledged that the German government had the right to choose refugees ... ”](http://euromaidanpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Screenshot-of-Soviet-Story-made-2015-06-15-at-10.20.44-PM.png)

Still from the movie “The Soviet Story” showing an excerpt from a German archival document which in part reads “The Soviet representatives started with discussion of the Jewish question. The Germans expressed their view that Jews were not a nationality to them, and they disagreed that it was a question of race and religion, however [The USSR] acknowledged that the German government had the right to choose refugees ... ”

The two sides would eventually agree upon on something quite radical: in exchange for the Germans handing over any Ukrainians residing in Germany, Jews and German communists who had fled to the USSR would be forced back into the hands of the Germans. [2] Many of these would perish in the German concentration camps.

In Russia today, the topic of the Soviet-Nazi or Russian-Nazi collaboration remains buried, yet in true “pot calling the kettle black” spirit, Russia puts the blame for collaboration and atrocities on Ukraine, while perpetuating the historical myth that the Russians were blameless and have always been “anti-fascist.” In the context of today's conflict, it is a myth that Putin has found rather easy to perpetuate for propaganda purposes, because unfortunately Ukrainians have long been associated with the stigma of nationalism, even under Soviet rule. In this light, a number of Jewish commentaries and reports from the Polish underground resistance during early WWII routinely questioned the loyalty of Ukrainian elites in the Kresy to the Polish state, accusing them of collaborating with the Soviet invaders in September 1939, not because they were willing communists, but rather nationalists who wanted to build a Greater Ukraine “pod płaszczykiem współpracy” [under the guise of cooperation (Polish) - Ed.] with the Soviets. [3]

Even more prominent in the western mind are Ukrainian nationalists more than eager to build a Greater Ukraine “pod współpracy” with the Germans. In John-Paul Himka’s words, “It sometimes happens that Westerners know little about Ukrainians and Lithuanians except their reputation as anti-Semites and willing collaborators in the Holocaust.” Writing in April 1939 just before the outbreak of WWII, Leon Trotsky in his own fashion stated that

... [S]ince the latest murderous 'purge' in the Ukraine, no one in the West [Ukraine] wants to become part of the Kremlin satrapy which continues to bear the name of Soviet Ukraine. The worker and peasant masses in the Western Ukraine, in Bukovina, in the Carpatho-Ukraine are in a state of confusion: Where to turn? What to demand? This situation naturally shifts the leadership to the most reactionary Ukrainian cliques who express their “nationalism” by seeking to sell the Ukrainian people to one imperialism or another in return for a promise of fictitious independence. Upon this tragic confusion Hitler bases his policy in the Ukrainian question.”

But what was Hitler’s policy and how did it impact the Ukrainian peoples?

On 6 February 1933, a report was dispatched from the German consulate based in Odesa to Konstantin Von Neurath back in Berlin telling the tale of Ukraine's forced famine, the Holodomor, confiscation of grain from the peasants by "shock" brigades, how peasants were "handing over everything in their possession" and how the Soviets were failing to fulfill grain requisition plans. [4] Stalin had completed his most efficiently brutal genocide by the time Hitler assumed power in Germany, when the genocide of Jews and Slavs was but a concept yet to be fulfilled.

Ukraine was swallowed whole during Operation Barbarossa, which helped ensure that some of the worst atrocities of the Holocaust, happened on Ukrainian soil.

Nazi propaganda exploited Soviet crimes for cynical self-service. How Nazi propaganda would later treat for example the Katyń massacre is reasonably well understood. [5] But the Holodomor also appeared in Nazi propaganda, albeit in garbled form. In a speech on September 12 1936, Hitler used the image of the Starving Soviet to indict general Marxist-ideological failings and compared it to his own plans.

“If the Urals” he said “with their vast wealth of raw materials, Siberia with its rich forests, and the Ukraine with its vast fields of grain were in Germany, it would be swimming in surplus under National Socialist leadership. We would produce and every single German would have more than enough to live on. But in Russia the population is starving in these huge areas because a Jewish-Bolshevist leadership is incapable of organizing production and thus according the worker practical help.” Germans would go on to conduct a cynical and Anti-Semitic hearts-and-minds campaign over the peoples they had conquered during Operation Barbarossa.

But despite posing as liberators from the starvation and misery inflicted by “Godless” or “Jewish” Bolshevism, as Nazi propaganda put it, Hitler’s planners also used starvation as a weapon, killings millions of designated “racial enemies” the Slavs, including Ukrainians. On August 11 1939, Hitler told Carl Burckhardt that he needed control of Ukraine so that “no one can starve us out as they did in the last war.” In Nazi genocidal thinking, keeping the Germans at home fed would come at the complete expense of the peoples of Eastern Europe. Discussing what the possibility of starving millions of Ukrainians meant, armaments specialist Hans Laykauf wrote on December 2 1941:

Scooping off the agricultural surplus in the Ukraine for the purpose of feeding the Reich is therefore only feasible if traffic in the interior of the Ukraine is diminished to a minimum. The attempt will be made to achieve this:

- by annihilation of superfluous eaters (Jews, population of the Ukrainian big cities, which like Kyiv do not receive any supplies at all);

- by extreme reduction of the rations allocated to the Ukrainians in the remaining cities;

- by decrease of the food of the farming population. [...]

When we shoot the Jews to death, allow the POWs to die, expose considerable portions of the urban population to starvation and in the upcoming year also lose a part of the rural population to hunger, the question remains to be answered: who is actually supposed to produce economic values? [6]

Under the Generalplan Ost, the German master-plan for colonisation of the East of Europe, 65% of the inhabitants of western Ukraine would either be starved to death or scheduled to be deported to Siberia.

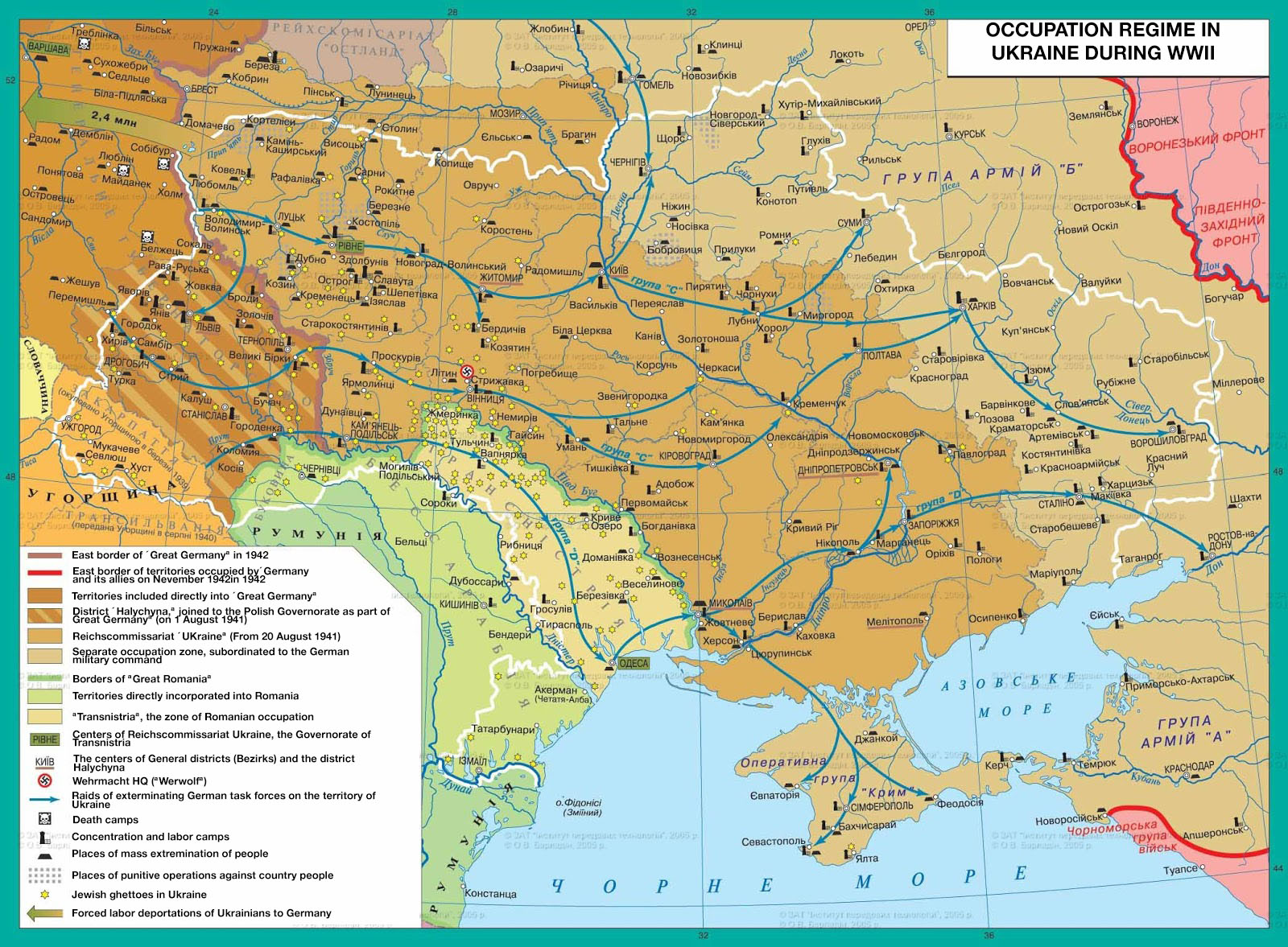

Regardless of Laykauf’s short term thinking, in the long run the answer to his question was going to be the Germans themselves. The very concepts of “Ukraine” as a state and “Ukrainian” as a people were going to be eliminated, and the territory of Ukraine, like the territory of Russia was going to become Lebensraum - Germanised and colonised “Living Space” for the German volk. To this end, under German rule the Ukrainian lands were going to be partitioned, the largest portion of which (with over 17 million inhabitants) came in the form of a civil administrative territory approved by Hitler on August 21 1941 designed to oversee the Germanification of most of Western Ukraine and including territory outside of Ukraine's contemporary borders - The Reichskommissariat Ukraine. It was to be headed by Erich Koch, a man who is on record as having stated, "If I meet a Ukrainian worthy of being seated at my table, I must have him shot." [7]

Under the Generalplan Ost

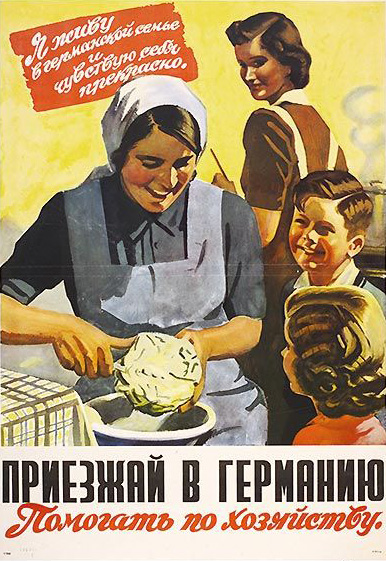

, the German master-plan for colonisation of the East of Europe, 65% of the inhabitants of western Ukraine would either be starved to death or scheduled to be deported to Siberia. [8] The rest would either be Germanised or serve as latter day helots to German overlords. During WWII over 2.4 million Ukrainians would find themselves being forcibly deported to Nazi Germany to work as “Ostarbeiters” - slave labourers in factories and servants to German families who had been indoctrinated by Nazi propaganda to view them as sub-human. Nazi propaganda in Russia and Ukraine depicted Ostarbeiter life as cheerful and voluntary, but in reality it was nothing of the sort.

But Hitler and his regime had one designated racial enemy beyond the Slav, and that was of course, the Jew. At the infamous Wannsee Conference on January 20 1942, it was agreed by all those present to step up the already ongoing extermination of all the Jews of Europe in line with Hitler’s wishes by means of "evacuation" (a favourite Nazi euphemism for genocide), i.e. forced deportation to the German concentration and extermination camps along with ghettoisation and liquidation. According to the minutes of that meeting, they estimated there were more than 11 million Jews throughout Europe to be killed. Reinhard Heydrich estimated that out of this number the European part of the USSR contained over 5 million Jews, Ukraine almost 3 million and that in and of itself was only a conservative estimate because according to Heydrich the numbers only incorporated those "who still adhere to the Jewish faith, since some countries still do not have a definition of the term 'Jew' according to racial principles." [9] That Ukraine had a proportionally high Jewish population (some of its towns such as Berdychiv were once known as “Little Jerusalems” for this reason) and the fact that, unlike Russia, Ukraine was swallowed whole during Operation Barbarossa, helped ensure that some of the worst atrocities of the Holocaust, happened on Ukrainian soil.

A foretaste of what was to come began on June 29 1941 in Lviv. Barely a week after the launch of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s Wehrmacht was already into western Ukraine. When the Germans entered Lviv they found that the city had been subject to a scorched earth policy conducted by the Soviets where anything deemed of value (munitions, factories etc) to the enemy that couldn’t be moved was destroyed. The Germans also found that the NKVD just before they fled the city had also executed 4000 political prisoners. It was this that served as a pretext to what followed. Antisemitic Nazi propaganda promptly slandered Lviv’s Jewish population by tying them to the NKVD murderers. The intent was to deflect any local anti-Soviet feeling directly onto the Jewish population and thus entice locals to become complicit in Hitler’s genocidal campaign.

The utilisation of Soviet atrocities as a means of winning locals to the Nazi cause would be a propaganda tactic repeated across the eastern front, including the Baltics, Belarus and even Russia itself. This tactic was not specific to Ukraine, however the poisonous effects of what the Germans did and the way they utilised local nationalist collaborators practically everywhere they went lives on to this day. Within the course of a month in Lviv from the day it was captured, at least an estimated 6,000 Jews perished via a series of pogroms organised by the Germans along with Ukrainian nationalists. That the Germans had Ukrainian nationalist help is not in dispute although some controversy persists over the role of Roman Shukhevych and the Nachtigall Battalion. Not for nothing has Lviv in June-July 1941 been called “a nightmare of carnage and chaos.” [10]

Trailer for “A Mentsh.” A documentary film made in the Yiddish language about the tragedy of Lviv’s Jews in WWII and a man who wants to keep the memory of Lviv’s Jews alive. The term “a Mentsh” refers to a good person full of love and empathy.

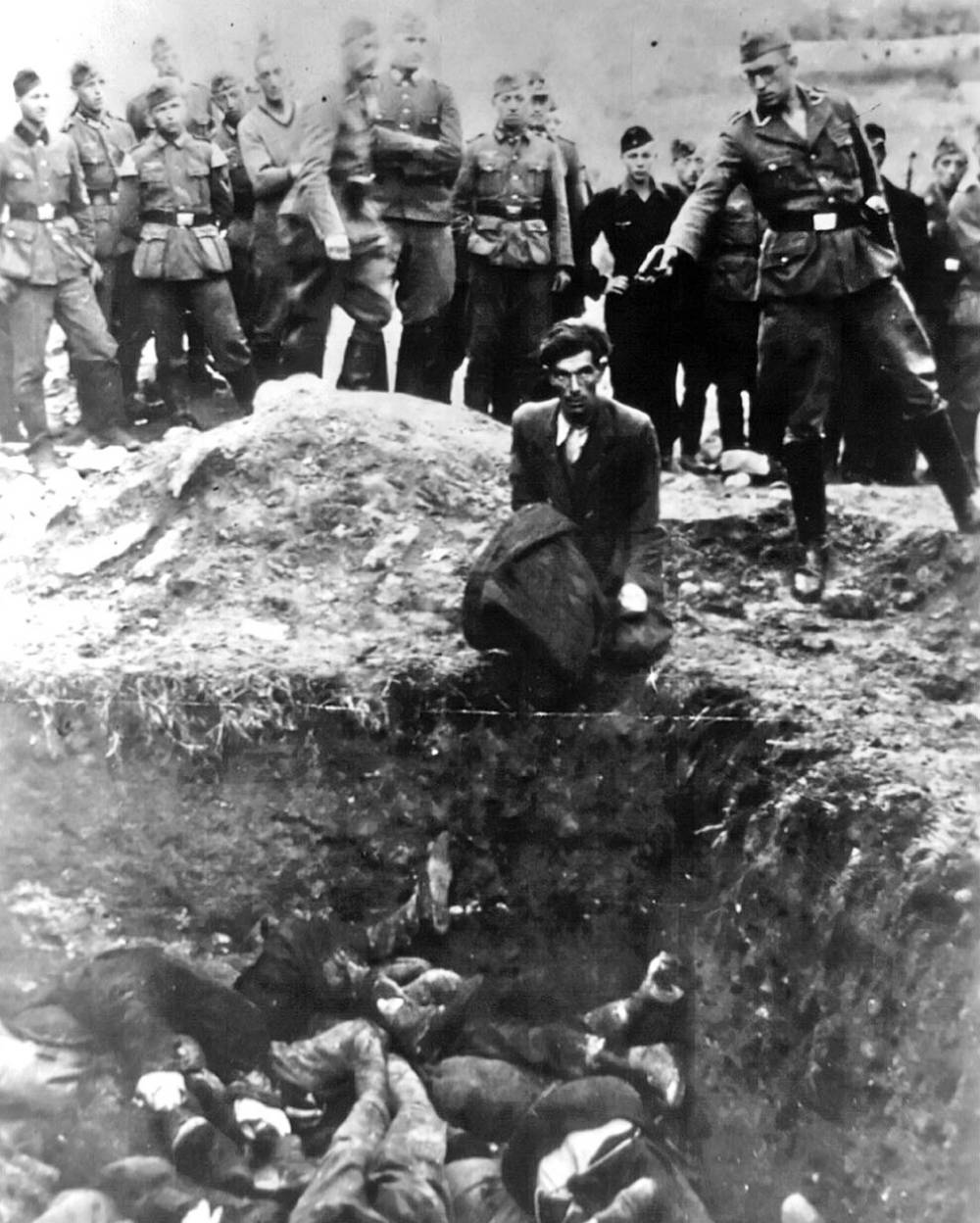

Throughout the German occupation, organised pogroms became a sad feature across the Ukrainian countryside. By far and away the most infamous atrocity of the Holocaust on Ukrainian soil is the Babyn-Yar massacre. On September 19 1941 the Germans captured Kyiv. Here as elsewhere on the eastern front, the retreating NKVD put into practice their scorched earth policy by dynamiting and setting fire to buildings deemed useful to the enemy. The Germans made no attempt to put these fires out. Instead they were used as the pretext to round up Kyiv’s Jews.

On September 29, orders in Russian and Ukrainian were given by the Germans on pain of death for all Jews to come to a Jewish cemetery near vul. Dorogozhytska with their belongings. Here they would be stripped before being force-marched under German and local nationalist collaborators to the Babyn-Yar ravine just outside Kyiv. At Babyn-Yar and within the space of just 2 days, almost 34,000 Jews would be shot and buried in mass graves - arguably the largest single massacre of Jews in the Holocaust.

The Germans would continue to use Babyn-Yar as an execution site for thousands more Jews, Soviet POWs and other “racial enemies” for a further 2 years. Exactly how many are buried at Babyn-Yar is still unknown, but totals of 150,000 victims are not out of the question. [11] Here it is worth noting that after WWII Soviet antisemitism together with official aversion to acknowledging the Holocaust on its territory prevented authorities from allowing a single memorial at Babyn-Yar to commemorate the mass of Jewish victims. In 1961 the Soviet writer Yevgeniy Yevtushenko published a poem dedicated to the Jewish victims of “Babi-Yar” and which also condemned Nazi and Soviet Antisemitism. The Soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich then set his poetry to music and in the following year premiered his Symphony No13 based on Yevtushenko and Jewish themes.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No13

Both Yevtushenko and Shostakovich were pressured by the Soviet state to change their works of art so that “Jewish suffering” became “Soviet suffering” and thus maintain the state line that denied the special nature of the Holocaust in Ukraine against the Jews of Ukraine. [12] It was only after the collapse of the USSR that the Jewish victims at Babyn-Yar could be properly recognised.

All in all by war's end, the Jews of the Ukrainian SSR had been devastated by the Holocaust. In 1986 the American historian Lucy Dawidowicz published a list of the number of Jews exterminated by country based upon pre-war censuses. By that list the Ukrainian SSR had a Jewish population of 1.5 million of which 900,000 died between 1942-44, representing a 60% death total. By contrast using the numbers of Dawidowicz, only 11% of the Jewish population of the RSFSR (107,000 out of 975,000) became direct victims of the Holocaust. [13] In a more recent survey, 1.5 million Jews are deemed to have perished throughout the whole of what is now Ukraine, which is more than half of Heydrich’s estimate for the total number of Jews of Ukraine!

Ukraine's high losses of Jews compared to Russia’s Jews are due to the fact that only a portion of western Russia proper fell into the hands of the Wehrmacht and even the territory they conquered was occupied for less time than the Ukrainian territory. If the modern day Russian state is in any mood for cynical gloating over this, it shouldn’t! After all, Russia has yet to come to terms with the Nazi-Soviet Alliance that existed between 1939-41 and in fact started World War II. But under German plans, what happened in Ukraine was going to happen in Russia too. Not only would the Russian Jews be exterminated, the Wehrmacht would have had the help of Russian nationalists to assist them.

60% of Ukraine's Jews had perished in the Holocaust

Just beyond the north east of Ukraine lies the Russian city of Bryansk. On October 6 1941 this city was captured by the Germans, after which local Russian nationalist collaborators actually went beyond their Ukrainian counterparts and quickly established a semi-autonomous “Lokot autonomy.” Arguably the most famous of the Lokot collaborators was Bronislav Kaminski who would go on to earn notoriety for his role in the crushing of the Warsaw uprising of 1944. The “Lokot autonomy” only lasted until August 1943, by which time the whole area it covered had been rendered “Jew-free” and remarkably without the Wehrmacht supervision or organisation that was present in the Holocaust in Ukraine.

Another telling statistic of note is the numbers of “Righteous Among the Nations.” Russia only has 197 persons recognised for their heroism in saving Jews from slaughter during the Holocaust, compared to Ukraine which currently has 2,515 such persons. Only Poland, France and the Netherlands have more!

Whilst Putin and his ilk continue to point out that Ukrainians made the mistake of welcoming the Germans as liberators, they seem to forget that it ever happened in Russia. The reality is different. This footage shows a parade of the Wehrmacht and local Nazi collaborators and supporters held in Pskov on June 22 1943. Even so, regardless of how useful a Russian or a Ukrainian could be to the Germans in the interim, when it came to the matter of exterminating the Jews of Europe, Russians and Ukrainians were nonetheless still considered “sub-human” to the Germans.

If there is one Ukrainian nationalist that has earned infamy over and above all others, it is Stepan Bandera.

Even before WWII Bandera’s name had been associated with bloodshed in Poland, notably the assassination of the Polish politician Bronisław Pieracki in 1934, for which Bandera was imprisoned at Wronki. Before his imprisonment Bandera was already climbing up the ranks of the OUN (Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists) which up until 1938 had been led by Yehven Konovalets. Konovalets' assassination by an NKVD operative quickly prompted a leadership struggle between Stepan Bandera and another somewhat more conservative nationalist, Andriy Melnyk. The followers of each would eventually become known as the OUN(b) an OUN(m). Not that Wilhelm Canaris, head of German military intelligence (Abwehr

) initially cared too much about this, as the OUN received cash from him in exchange for intelligence about Poland. The Abwehr cash given to the OUN is rather well known, even if others in the Nazi leadership such as Alfred Rosenberg were more fickle about funding the OUN. [14] In September 1939 Bandera managed to escape from Wronki after which he stayed in Kraków where he built his personal base of followers and plotted an armed uprising in Soviet-occupied Ukraine.

On 30 June 1941 after the Germans had marched into Lviv, Bandera’s OUN(b) proclaimed the “Declaration of Ukrainian Independence,” Point 3 of which proclaimed that the new Ukraine would work with Nazi Germany. These facts have given Bandera the reputation of being a would-be Ukrainian Quisling. But the Germans were not in any mood to tolerate a new independent Ukraine, regardless of how much it may or may not have collaborated with Hitler’s wishes. There would not even be an equivalent of the “Lokot autonomy” here, and so on 6 July 1941 Bandera was arrested. He would eventually be placed into the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany. As for Melnyk, he would also end up at Sachsenhausen after trying to proclaim an independent council in Kyiv.

Despite his imprisonment, how culpable is Bandera for the actions his followers undertook during his imprisonment? One of the most notorious acts of bloodshed that the Bandera name is associated with are the massacres of perhaps up to 100,000 Poles (and Ukrainians) in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia in 1943-44. The blame for these massacres usually falls on both the OUN(b) and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). Although the OUN and UPA weren’t technically one and the same, many OUN members served as UPA soldiers and officers, and vice versa. What this means is that those in the UPA who took part in the Volhynia and Eastern Galicia massacres would still have been Bandera followers. According to this analysis, Bandera wasn’t directly involved, which may be true. But if it can be argued that those who initiated the massacres believed that in doing so they were exercising a spirit of Bandera which demanded a Ukraine free of Poles, then Bandera cannot be completely excused from blame for imbibing that spirit. [15]

What happened in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia remains an uncomfortable history for Ukrainians and Poles to read, but even here, there are some genuine Ukrainian heroes. Romuald Niedzielko has documented over 1,340 cases of Ukrainians who risked their own lives to save Poles from these massacres. Despite these massacres which have long soured Polish-Ukrainian relations, there is still good hope that true reconciliation between Poland and Ukraine is possible in the same way Germany now has good relations with Poland and Israel. Last year Poroshenko tried to urge that reconciliation by insisting Poles and Ukrainians must forgive each other for past mistakes. Now there is a planned joint Polish-Ukrainian Historical Commission to investigate the massacres.

It is in continuing efforts to recognize its history that Ukraine has recently passed what some view as controversial "history laws" recognising the UPA as fighters for Ukrainian independence. Whatever flaws of Ukrainian historiography critics see in these laws, for example, that they may prohibit academic discussion of the nastier side of the UPA, for example, Ukraine is still in a far, far superior position than Russia is currently in facing the nastiest aspects of its history. It is a history of Ukrainians serving as “Hilfswilligers” and including “Trawnikis,” such as Ivan “the terrible” aka “John” Demjanuk who served as a concentration camp guard at Sobibor. Ukrainians also served in General Vlasov’s “Russian Liberation Army” to the Waffen SS Galicia division, formed in 1943 as the eastern front was sagging and as the Germans were desperately looking for any allies even if it meant temporarily compromising on their “racial principles” to try and stop the Red Army from advancing. In 1944 this Waffen SS division found itself annihilated near Brody, after which its battered remains were re-organised and sent to conduct anti-partisan activity in the Balkans and on the Austrian border. In 1945 the remnants of this division surrendered to the western allies. Other remnants were sent to France for retraining and to do likewise to the French resistance, but here they proved less than reliable for the Germans as many Ukrainian servicemen simply defected (or attempted to defect) to the French resistance. For Osyp Krukovsky

, joining the French resistance completed a circle of military service which saw him fight on both sides of the war. He had originally enlisted into the French Army on September 7 1939. [16]

In 1944, both Melnyk and Bandera were released by the Germans in the vain hope that both would conduct anti-Soviet activities and thus slow the Red Army advance in Ukraine. Also released that year from German captivity was Pavlo Shandruk who had served with the Poles in September 1939 and who won a Virtuti Militari, Poland’s highest military decoration for bravery against the Germans before being imprisoned. Shandruk was to chair a “Ukrainian National Committee,” a German puppet government but which was only recognised on 12 March 1945. But Shandruk had other ideas. After reorganising the Ukrainians serving in the Wehrmacht such as the Waffen SS Galicia into a “Ukrainian National Army” he promptly had them move westward to surrender to the western allies in both Germany and Italy. Shandruk also lobbied Władysław Anders to have them recognised as pre-war Polish citizens (regardless of whether this was true or not) so that they would be saved from Soviet deportation and the Gulag camps. As with the Ukrainians who served in the French Foreign Legion, the dark question of “did this allow war criminals to avoid prosecution?” still looms over the men Shandruk spared from the Gulag, particularly over the men who served in the Waffen SS Galicia. In 2013 the pursuit of this question led to a rather bizarre situation over two men currently living in the US who by simple coincidence happen to share the same name Michael Karkoc.

Conclusion

In Ukraine, the era of Soviet-influenced historiography is now coming to an end. As a result, the Holocaust that the USSR denied for so long, as well as the true role of Ukrainians in WWII - good and bad, can finally have a chance to be openly discussed and given proper contextualisation. As I typed these words this BBC news article was published about the taboos concerning the Holocaust created under Soviet rule now being lifted in Ukraine. As a result, Holocaust memorials are being erected in Ukraine and younger generations will have the chance to learn facts that their parents and grandparents were denied under Soviet education.

What future generations will learn about Ukraine’s Nazi collaborators, whether they were willing or forced to collaborate under threat of death, will undoubtedly be difficult to swallow and will make for uncomfortable reading. But Ukrainian history is far from a simple history. It’s very complexity has led to the persistence of some very crude stereotypes held in the West and which Putin and his entourage have tried to tie to today's situation.

Jan 12, 42: “Russia’s defeat should provide Ukraine with opportunity to join Europe’s political system” – Ukrainian nationalists to Hitler

— RT's WWII Tweets (@Voina_41_45eng) January 12, 2015

One of the many tweets from @Voina_41_45, RT’s account dedicated to covering WWII. The phrase “Europe’s political system” here is an obvious double entendre.

We know the tropes; Russian state press depicted the Euromaidan protests as some kind of Bandera coup and the current leadership a fascist Junta. These arguments have been refuted over and over again. For all of Poroshenko's flaws, he has never had a high-ranking military career and is certainly not akin to a Prayut Chan-ocha (whom Putin seems to support). Nor has he had a career as a KGB thug in the same way Putin has. As for Bandera, it’s inconceivable he would ever approve of a revolution in the name of democracy for Ukraine's freedom started by someone of Muslim faith in which not just Ukrainians but Belarusians, Armenians, Georgians, Tatars and even Russians all took part and died (two of the Heavenly Hundred, Igor Tkachuk and Mykola Dziavulsky were born in Russia). And Bandera’s most fanatical modern followers (namely “Right Sector” and “Svoboda”) have been decisively rejected at the national ballot box since. Whereas in Russia the man who says the Nazi-Soviet pact is “justified” enjoys the kind of consistently high approval rating that only a tyrant who injects a fascist style cult of personality and who brainwashes his people with hatred and lies can enjoy.

In World War II the number of Ukrainians who took up arms and fought for the allies (here including the USSR) far outnumbered those who, forcibly or otherwise, took up arms or collaborated with the Germans. As I said in Part 1, not all Ukrainians in WWII can be painted with the same brush and certainly not the crude one coming out from the Kremlin. In total, Ukrainian war losses against the Germans were proportionally far higher than Russian war losses. To paraphrase Norman Davies here, if you think all Ukrainians were nationalists but all the Red Army combatants were “Russian,” you need to think a bit harder!

[hr]Prior articles in this series:

Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 1

Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 2. Stories of Ukrainians in the Red Army

[1] Here it must be stated that Khatyń should not be confused with Katyń. Because of the extremely similar names of the two in the USSR a campaign was deliberately conducted after WWII to commemorate the victims of the 1943 Khatyń massacre as a means of deflecting attention from the memory of the Soviet massacre of nearly 22,000 Polish POWs.

[2] N. Davies, God’s playground: A history of Poland. Vol 2, p444.

[3] For more details on the matter see C. Mick, Incompatible Experiences: Poles, Ukrainians and Jews in Lviv under Soviet and German Occupation, 1939-44.

[4] J. Bednarek et al., Poland and Ukraine in the 1930’s – 1940’s, Unknown Documents from the Archives of the Secret Services. Holodomor The Great Famine in Ukraine. 1932–1933, No 98, p289-90.

[5] See K. Ledford, Mass Murderers Discover Mass Murder: the Germans and Katyń, 1943

[6] As cited in Nuremberg Trials document 3257-PS. Quoted in S. Welch, “'The Annihilation of Superfluous Eaters': Nazi Plans for and Uses of Famine in Eastern Europe”

[7] As quoted in Koch’s Wikipedia page

[8] V. Kosyk, The Third Reich and Ukraine, p261.

[9] A full translation of the minutes of the Wannsee Conference can be accessed here.

[10] M. Gilbert, Second World War (revised edition), p204.

[11] P. Magosci, A History of Ukraine, p633.

[12] For more on Yevtushenko and Shostakovich see M. Wigglesworth, “Mark’s notes on Shostakovich’s Symphony no13.”

[13] L. Dawidowicz, The War against the Jews, p403. Also cited here. A similar figure is also offered by P. Magosci, Op cit., p633.

[14] Wilhelm Canaris was head of the Abwehr until 1944. Here it must be noted that the character of Canaris is somewhat enigmatic. Whilst it is clear Canaris was himself a German nationalist, he also personally despised Hitler. On the basis of allegedly passing intelligence to Germany’s enemies, he was arrested and executed in Flossenbürg concentration camp on April 9 1945. Alfred Rosenberg who was in a position to also fund the OUN distrusted it for being too rooted in “Austrian Galicia”. See C. Hale, Hitler’s foreign executioners: Europe’s dirty secret, p143-44.

[15] Such an analysis of this type wouldn’t be too dissimilar to Ian Kershaw’s “working towards the fuhrer” concept as an analysis of the relationship between Hitler and his subordinates. Hitler was a distant ruler, although the difference between Hitler and Bandera was that Hitler chose distant rule. Bandera was forced to be distant by his imprisonment.

[16] For more on Krukovsky and the Waffen SS Galicia division, see M. Logusz, Galicia Division: The Waffen-SS 14th grenadier Division 1943-1945.