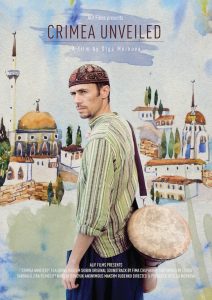

The red potter’s wheel whirls anti-clockwise, turning round and round while artisan hands expertly coax a new vase from a lump of clay – a recurring image in director Olga Morkova’s documentary film “Crimea Unveiled”, screened at the Ukrainian Institute in New York on March 25th.

This potter’s wheel was a symbol for the central figure of the film, artist Rustem Skibin – a Crimean Tatar forced to relocate to Kyiv upon the Russian invasion. The plight of one skilled craftsman, a vanishing art form, the tragic decline of a culture and a whole nation – these were the larger themes of the documentary.

Mr. Skibin now continues to produce his traditional ethnic pottery in Kyiv. But the consequences of Russian invasion and annexation continue to be disastrous for indigenous Tatars in Crimea. The film ends with Ms. Morkova’s words: “We don’t know what will happen, but we must be patient. We will wait and submit ourselves to the whirl of the universe.” For Crimean Tatars, the potter’s wheel keeps turning…

Following the film, Ayla Bakkalli, USA. representative of the Indigenous Crimean Tatar Mejlis (their highest executive-representative body), expanded on the history and present situation of Crimean Tatars. (Ms. Bakkalli traces her ancestry back to two strands of Tatars in Crimea – one to the 12th century and the other to nomads several millennia ago.)

Ms. Morkova’s beautifully crafted short film related how almost all Crimean Tatar artists and artisans died off in Uzbekistan, where their entire Crimean population was forcibly exiled in cattle cars by the Soviets in 1944. More than 100,000 deportees perished from starvation and disease. Following Ukrainian independence, about 250,000 had returned. Then, in 2014, came the “little green men.”

The film’s director Olga Morkova, a Ukrainian of Russian origin from Sevastopol, explained how “Crimea Unveiled” afforded her the opportunity to show “the other Crimea, not just like other destitute and wretched displaced peoples in the world, but artists who are committed to carry on their culture.” The sponsors listed for her documentary include the US Embassy in Kyiv, the Fulbright Association, and the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation. Ms. Morkova has now initiated her next project – a documentary about Mustafa Dzhemilev, leader of Crimean Tatar National Movement and a member of the Ukrainian Parliament since 1988. This will be produced by Crimea SOS Initiative in Kyiv.

In her talk, Ms. Bakkalli said there is no question where Tatars’ sympathies and allegiance lie: “We Crimean Tatars told our Russian neighbors, we are more Ukrainian than you. The Russians were always imperialists, never the Ukrainians. Our genocide began with Catherine II and her confiscation of our lands. We assess historical facts to fight Russian propaganda. All Crimean Tatars want to be with Ukraine because a strong Ukraine means peace. Currently we see a return to horrific Soviet times; now the world has been destroyed…”

Ms. Bakkalli added that rarely mentioned are the current penalties for not embracing Russian citizenship (which amounts to de facto recognition of Crimea as part of Russia): no right to work in the public sector, no drivers license and you cannot study in state schools. Most civil servants are now Russians. Coupled with harsh censorship, police state monitoring and an absence of democracy, it is no wonder that Tatars fear Crimea becoming another Ossetia or Abkhazia scenario.

According to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHRC), over 20,000 uprooted Crimeans fled across the newly established borders to find haven in Ukraine. And the systemic human rights abuses by Russian occupiers keep escalating, with banning of public events and restrictions on elemental freedoms of association. Hardly reported were the recent severe beatings of two Tatars on a Crimean bus just for speaking their native language. Others fared much worse. Ms. Bakkalli described one 39-year old who wanted to enlist in the Ukrainian army; he was killed and his mutilated body thrown out in a bazaar. Even non-activists are found hung or killed.

One of Ms. Bakkalli’s slides showed a young Tatar woman under a Crimean flag during Maidan. On a light blue background, this official flag features a golden symbol – the “tamga”, which suggests an inverted “tryzub” or trident, but is actually an abstract tribal seal historically used by Eurasian nomads. The captions revealed this Tatar girl spoke in Ukrainian: “Maidan is a Tatar word… we are proud to be Ukrainian.”

Ms. Bakkalli cautioned that any videos showing “Crimean Tatar” support for Russia are just Moscow propaganda taking advantage of a different group, the Khazar Tatars, instead of the Crimean Tatars, who are all pro-Ukraine.

Responding to a question about why there is so little official action from Türkiye and other Muslim states, Ms. Bakkalli stated there are currently 5 million Crimean Tatars living in Türkiye. While their is widespread grass roots support, the Turkish-Russian energy agreements complicate the political situation. She continued: “Even much of the Muslim world is hearing of Crimean Tatars for the first time. The Middle East is volatile with its own issues, which does not leave much room for Crimean Tatars.”

In a private conversation with this author, Ms. Bakkalli added: “The Crimean Tatars are much more modern; our women do not wear veils. We also need to remember that Crimean Tatars were content to live in a democratic Ukraine for almost a quarter of a century.”

Perhaps the most important point made by Ms. Bakkalli was the significance of the April 2014 official declaration by Ukraine that the Crimean Tatars are the indigenous people of Crimea and the recognition of their self-governance by the Mejlis. (Ms. Bakkalli is also Advisor on Indigenous Matters to the Permanent Mission of Ukraine to the United Nations.)

With this decisive action, Crimea now falls under international norms and becomes part of a much larger global forum of 370 million indigenous peoples world-wide. For Ukraine this is critical because it provides additional compelling legal arguments against Russian claims and annexation of the Crimean peninsula.

This article first appeared in The Ukrainian Weekly, April 12, 2015