In the year since Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution, Russia has done much to undermine Ukraine’s sovereignty. It annexed Crimea and began a war along Russia’s border with Ukraine. In his remarks from a March 2, 2015 conference entitled “Ukraine, Russia and the EU: Europe, a Year after Crimea Annexation” held in Berlin, historian Timothy Snyder examines the tactics used in Russia’s recent aggressive actions in Ukraine against the backdrop of European history, and, specifically the history and memory of World War II. His insights and conclusions are important for anyone interested in looking critically at what is happening in Ukraine, Russia, and Europe today, and how it is we got here.

What does it mean to rehabilitate the history of the Soviet Union when part of the history of the Soviet Union is precisely the history of contact with Nazi Germany?

Snyder argues that Russia’s threat to Ukraine is but one aspect of a much larger strategy that threatens the entire European order. The enormous stress that Ukrainian and European institutions are under today due to Russia’s actions are “precisely the point” of Russia’s attempt to destabilize and dismantle not only Ukraine, but Europe. Moreover, Russian propaganda manipulates our understanding of European history, channeling our memories in a way that exports its own responsibility for the Soviet Union’s crimes during World War II. Snyder presents and historically contextualizes two literary examples, one from a Gulag memoir, the other from a WB Yeats poem, to show how the steady, progressive dismantling of an integral whole into its constituent parts is as much the essence of Russian totalitarian propaganda in the past as it is now. The strategy is the same, whether breaking a political prisoner in the Gulag or dismantling a nation or union of nations.

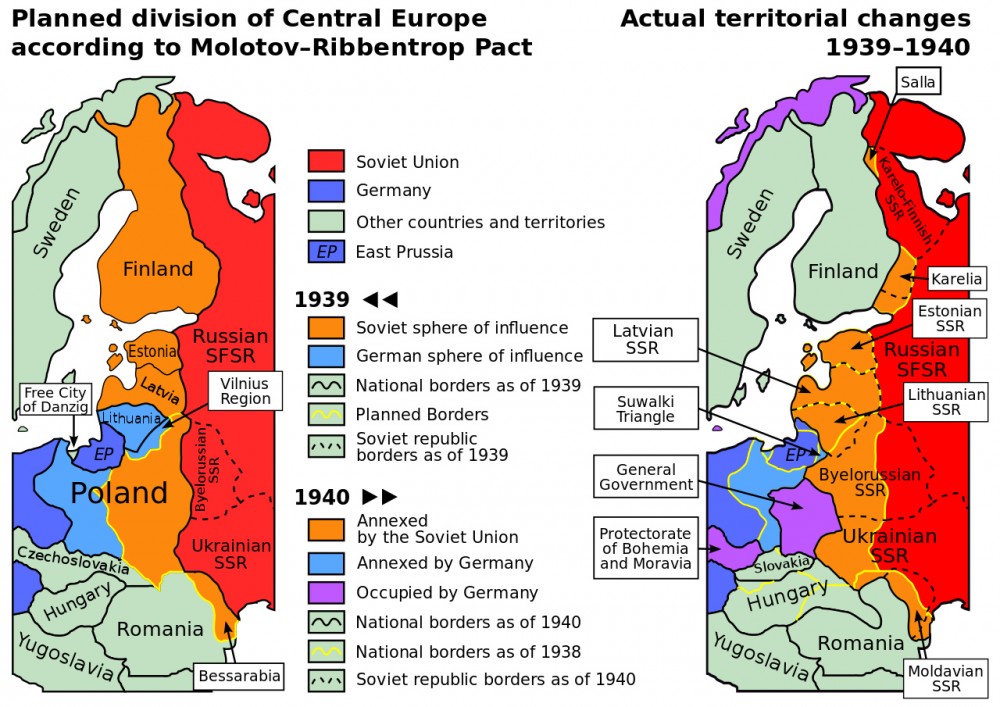

Snyder begins with a discussion of the last time Europe was divided and European systems were destroyed. He considers the signing by Hitler and Stalin in 1939 of the now infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as the beginning of the end of the European order. The Pact in effect made the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany allies, who then proceeded to invade and divide a good deal of Eastern Europe between them. “Stalin made an alliance with Hitler in order to turn European energies against themselves,” states Snyder.

The reason why Putin makes an alliance with the Far Right is to destroy the European Union. It’s the exact same line of thinking

For most of the 20th century Russia viewed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as abhorrent. As recently as 2009, Russian President Putin considered the Pact “immoral.” However, just a few months ago in November 2014, and to the dismay of observers, President Putin stated that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact wasn’t that bad after all. “The Soviet Union just didn’t want to go to war. What’s so bad about that?” In so stating, Putin in effect rehabilitated the very Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that began the Second World War. Moreover, Snyder adds, Putin rehabilitated the Pact for the exact reasons that Stalin made the agreement in the first place. Just as Stalin pursued a strategy of alliances with Hitler to undo European order, Putin too is currently pursuing a strategy of alliances with the extreme right in Europe. “The reason why Putin makes an alliance with the Far Right is to destroy the European Union. It’s the exact same line of thinking,” says Snyder.

As awful as this seems, Snyder argues that something much deeper is going on with Putin’s rehabilitating an alliance that began a world war. Snyder points out that there is “a deeper abyss” here, one in which the responsibility for the crimes of World War II and the Holocaust that occurred within the Soviet Union is shifted onto other ethnicities and nationalities. This is precisely what we hear in Russia’s rhetoric about Ukraine’s “junta” and “fascist Kyiv coup.” More importantly, such a shift leaves an enormous chapter of history uninvestigated and unconfronted. This thesis takes some unpacking, which Snyder accomplishes by examining how we view and remember historical events.

Viewed from the prism of the West, our memory of the Holocaust is of the horrific concentration camps and images of trains. World War II, however, began as a shooting war, and the camps and trains came later.

But of course, the Holocaust began as a shooting campaign in Eastern Europe, carried out by Germans and local people of many ethnicities. And it took place all the way east as far as German troops went. Russians took part in the Holocaust too. And this is an uninvestigated and unconfronted chapter of history. The one thing that almost all of them had in common was a Soviet passport. They had either joined the Soviet Union in 1939 or 1940 when the Soviet Union expanded westward or they were citizens of the pre-war Soviet Union. Either way, the Holocaust as it began and the Holocaust in which half of the Jewish victims died was carried out on the territories which had been the Soviet Union with the massive collaboration of Soviet citizens. I say Soviet citizens because all attempts to classify them by ethnicity have to fail. Attempts to classify them I think by ethnicity is usually someone’s nationalism fighting against someone else’s nationalism. Now the Holocaust took place all the way east as far as German troops went. It took place in Smolensk, it took place in Kaluga, as far east as German troops went. Russians and others took part in the Holocaust. I stress this not to single out Russians, who behaved exactly as everyone else did in this situation. I say this to stress that there’s a great uninvestigated chapter of history here, a great unconfronted chapter of history here. And the question I’m trying to ask … What does it mean to rehabilitate 1939? What does it mean to rehabilitate an alliance with Adolph Hitler when there is no prior confrontation with Nazi war crimes on your own territory? … What does it mean to rehabilitate the history of the Soviet Union when part of the history of the Soviet Union is precisely the history of contact with Nazi Germany?

It is significant that our very memory of the Holocaust and the crimes of WWII is from Soviet sources, and from the recollections of Soviet citizens, Jews and others. The Soviet Union, and Russia afterwards, has channeled the memory of as well as the blame for these crimes away from itself and towards others. Russia has in effect channeled the tremendous political energy arising from these crimes toward ethnicities that were already disliked for other reasons. “Soviet propaganda tried very hard to associate the Holocaust with Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and western Ukrainians.” There were indeed plenty of Holocaust perpetrators in those countries. But there were also many Holocaust perpetrators in other places, including Russia, which seems to have escaped blame almost entirely.

The Soviet Union also exported blame for these crimes to the West, its capitalist system, and to fascism, as a general category. And, of course, it created the myth that all the evil deeds of fascism were undone by Russia in the Great Fatherland War.

Snyder argues that this export of responsibility for history is happening again today. “Just as then, so now, blame for the Soviet past or blame for the Nazi past in the Soviet Union is exported, is externalized. Now all of the Ukrainians are somehow fascists.” Even though Ukraine in fact suffered proportionally much more in World War II than Russia, the Ukrainians are now presented as the “fascists”. The blame is thus ethnicized all over again. Fascism as an idea, and the West as backers of this idea, has been fully resuscitated. That is the familiar refrain we hear daily from Russian state media. The legitimate government of President Yanukovych was overthrown by a fascist junta with the help of the US secret services and the like. This is quintessential Soviet reasoning and Soviet style myth-making.

What’s bizarre about this resuscitation of Soviet mythology and Soviet-style externalization of responsibility is that it is taking place at the same time as the history of Russia’s cooperation with Nazi Germany is also being rehabilitated. “This is where things start to get truly dark and truly strange,” remarks Snyder.

Russia presents itself as anti-fascist while it is in reality being pro-fascist. To embrace both of these legacies at the same time, Snyder goes on to argue, means that Russia is actively shifting its war mythology from a defensive stance to an offensive one. He believes we are likely to see the commemoration of the Great Fatherland War, which was indeed a defensive war, being used as the justification for an offensive war in Ukraine. “There’s a slippage of Russian memory going on in which a defensive war is becoming an offensive war.”

For those in the West, of course, what is being exported is a giant contradiction. Russia is clearly moving way to the right, yet at the same time, we see Russia proclaim that it is everyone else that is moving to the right. Here Snyder invokes a classic passage from WB Yeats’ The Second Coming, a moving poem written in 1919 in the aftermath of the First World War:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Snyder argues that as in this passage, Russia’s fundamental contradiction and tension between pro-fascism and anti-fascism is part of a larger strategic policy which has been “loosed upon” the West and from which the West is currently suffering. It is part of a larger policy of making things fall apart, indeed of making Europe fall apart. “Russia does not have a proposal for a better Europe. There is, however, a Russian strategy for making the Europe that exists fall apart.”

Snyder goes on to list some of the “symptoms” of Russia’s disintegration strategy already encountered in Europe:

- support of client states inside the European Union;

- support of separatism from the European Union and separatism within European states;

- support of right-wing populism inside European Union member states;

- support of fascism, fascists and neo-Nazis inside the European Union;

- the provision of a political theory about how things should fall apart.

The fundamental political logic of the European Union is that there’s a positive relationship between civil society, sovereignty and integration. Civil society helps sovereignty, integration helps sovereignty. Where a sovereign state is weak, civil society can help. European integration can also help. The Russian proposition is to take away integration and to take away civil society, and leave sovereignty all by itself. That’s a different political theory…. This is not the version of Europe we have come to know.

Russian propaganda also uses contradiction and cacophony to confuse, distract, and generally interfere with processing thoughts.

Snyder then reveals some powerful insights and examples of how Kremlin propaganda has in fact succeeded in engaging our minds and how little we’ve noticed. Russia doesn’t just use the standard propaganda of lies and distortions. Russian propaganda also uses contradiction and cacophony to confuse, distract, and generally interfere with processing thoughts. From the contradictory ideology of being the “pro-fascist anti-fascist”–of supporting the right while claiming to be the left–to Putin’s rehabilitating the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, all of these contradictory positions and statements are in fact a deeply powerful form of Russian propaganda. And it has pervaded directly and indirectly how we talk about Ukraine, and therefore Europe and ourselves. “If I am a pro-fascist anti-fascist, I am filling your minds with things that contradict…. Contradiction is part of the point. The propaganda which has been “loosed upon” you … is meant to be contradictory. It is meant to make it impossible to think.”

If Nemtsov is murdered, then you claim it was the Ukrainians, you claim it was the Chechens, you claim it was the Islamic fundamentalists, you claim it was the opposition itself, you claim it was the American secret services. And by the time you’ve made all of these claims, it becomes harder to talk about what actually happened. There’s political marketing, another very important kind of propaganda, where, for example, you tell some people that Ukrainians are all anti-Semitic, and then you tell other people that Ukraine is part of the international Jewish conspiracy.… There is no Ukrainian state but the Ukrainian state is oppressive. There is no Ukrainian nation, but all Ukrainians are nationalists. There’s no Ukrainian language but Russians are being forced to speak it.

Snyder concludes that thus far the Kremlin has succeeded, though not quite as expected. Although in many ways Russia has won the war in Ukraine, things have actually gone much worse than the Kremlin anticipated. “Kharkiv is still in Ukraine. Odesa, still in Ukraine. Even a good deal of Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts are still in Ukraine. There’s no way the Russian offensive was about getting bits of Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts and Crimea. It was much more ambitious than that.” The propaganda tactics applied to Europe, on the other hand, have actually worked much better than the Kremlin expected. As a result, “what were the tactics have become the strategy.” In other words, what began as an anti-Ukraine European propaganda campaign, has now become a propaganda campaign directed against Europe itself. “Europe has proven to be a softer target than Ukraine.”