Wikipedia defines a troll as Internet slang for “a person who sows discord on the Internet by starting arguments or upsetting people, by posting inflammatory, extraneous, or off-topic messages in an online community… with the deliberate intent of provoking readers into an emotional response or of otherwise disrupting normal on-topic discussion.”

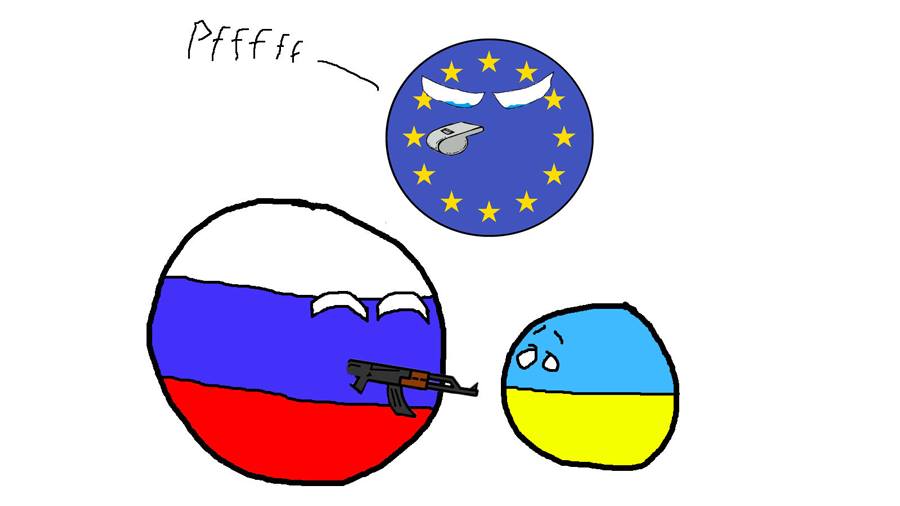

In the wake of the Crimean Anschluss, Moscow has deployed trolls against Ukraine, and Ukrainian news outlets have published long lists of people and sites they say feature the activity of pro-Putin trolls.

But there have been very few articles which consider Russian trolling from the inside, from the perspective of those Moscow is using for this purpose. An article on Sobaka.ru today in which someone who says she was recruited, trained and used as a troll against Ukraine provides an unusual glimpse into that world.

The site says that “Petersburg is glorified across all of Russia as the cradle of information wars and ‘Internet trolls,’ which took shape in an elite living complex in Olgino and later shifted closer to the center of the city.” Speaking on condition of anonymity, a former troll describes her life in its employ and why she didn’t last long in that capacity.

Many people who become trolls are attracted by ads that promise high pay but provide few details on what anyone hired would do. Those who apply, she says, are interviewed about their past employment and then asked to “’rewrite’” some real news story. One had the sense, she continues, that the group would hire anyone who could write and speak Russian.

And those who had been looking for a good job with high pay almost always said yes when told that they would begin at 45,000 rubles (750 US dollars) a month, she says, noting that no one asked any questions about their “personal political convictions” before they were offered a position.

On the first working day, which extended from 9:00 am to 5:30 pm, the former troll says, she and her colleagues were asked to come up with 20 news stories of which about 75 percent of the content was to be real and the rest invented. The office reminded her of a school, she says, one in which one would be fined for being late and required to leave promptly at the end.

The trolls were identified as employees of the Federal News Agency, and they put up most of their stories on Ukrainian sites, including ones like the Kharkov News Agency at nahnews.com.ua. Ostensibly in Ukraine, all those posting on it were based in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The anonymous former troll says she had the sense that she was part of “some kind of social experiment or reality show,” especially since the 20 or 30 trolls in her office at the time were constantly monitored by television cameras. Managers gave relatively little guidance except the obvious: no one was to criticize Putin and the separatists were to be called militants.

Her fellow trolls, she continues, were mostly young people from other cities with higher education and not stupid. Some were quite informal with piercings and the like. She divides them into three categories: those who had no real idea what they were doing, those who would do anything for money, and those who bought into the line. There were very few of the last.

The former troll says that her bosses were concerned only about boosting the number of visitors to the sites where she and the others operated. That led them to include stories about murders, rapes, crime, show business, and gays because those stories could be counted on to attract more attention than others.

It took her a long time to decide to stop trolling, she says, because the pay was so good and she feared she could not get another job with as high an income. But the job made her nervous and many of her friends oppose the Putin regime. Finally, “at a certain moment,” she says, she “understood that [she] was ashamed of saying what [she] was involved with.”