It is time to think about whether Ukraine needs territorial integrity if it threatens to paralyze the country and turn it into a conglomerate of regions that are oriented in opposing directions.

It is time to think about whether Ukraine needs territorial integrity if it threatens to paralyze the country and turn it into a conglomerate of regions that are oriented in opposing directions.

On the territory of the Donbas (referring in this article to the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts -Ed.) the wave of seizures of administrative buildings by Russian militants is spreading. Ukrainian law enforcement is unable to mount an effective counterattack. One can look for different reasons, but one obvious one is the inability of top government leadership to make decisions, caused by doubts about the loyalty of law enforcement and the support of the local population. Instead of offensive tactics, the tactic chosen it to isolate the region from the rest of the country, turning it into a kind of quarantined zone. As a result, an actual border has been created inside the country between the unstable Donbas and the remaining oblasts, where the pro-Russian forces are still only attempting to enflame the situation in the administrative centers in order to hold countless meetings and where the majority of the residents support the struggle against separatists.

However, Kyiv is attempting to negotiate a compromise with the Donbas, embodied in the old regional elites, as if this could calm the situation. The latest signals appear to suggest a softening of the demands by the regionals regarding the expansion of the rights of oblasts rather than federalization and granting the Russian language the status of regional, rather than state, official language. Tyzhden sources report that before Easter, the monopoly owner of the Party of Regions Rinat Akhmetov met with colleagues and decided to support territorial integrity. In turn, acting President Oleksandr Turchynov and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk stated in the Verkhovna Rada, on April 18, that the central government was ready to give the Russian language official status in the regions where a large minority of Russian speakers resides, and also to grant the individual local administrative units financial and economic autonomy. They even agreed to eliminate the oblast and district state administrations while shifting their authority to local elected bodies.

In this context, it is important to remember that territorial integrity is very necessary for any state, but that it still is much less important than the preservation of sovereignty and self-determination. Attempts to place territorial integrity above the state's ability to function normally and to develop dynamically can drive anyone into a trap similar to the ones where Bosnia and Herzegovina have ended up. However, there is the successful experience of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, which split peacefully in order to avoid confrontation on where and how to proceed.

In this context, it is important to remember that territorial integrity is very necessary for any state, but that it still is much less important than the preservation of sovereignty and self-determination. Attempts to place territorial integrity above the state's ability to function normally and to develop dynamically can drive anyone into a trap similar to the ones where Bosnia and Herzegovina have ended up. However, there is the successful experience of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, which split peacefully in order to avoid confrontation on where and how to proceed.

It is important to make sure the price of keeping the Donbas in Ukraine -- in other words, concessions to the regional elites -- does not become unreasonably high for the future of the entire state. After all, from the financial and economic perspective, as well as the ideological and political ones, this region has been a weight that for all these years has been holding back the market and democratic transformation of Ukraine, as well as its national consolidation and European and Euro-Atlantic integration.

Suitcase without a handle

The Donbas has traditionally provided the electoral base for reactionary and anti-European forces. This was the case during the last parliamentary elections, with 8.8 million people who voted for the Party of Regions and the Communist Party -- almost 30% (2.5 million) of the inhabitants of the region. In 2010, it provided 3.7 million out of 12.5 million votes for Yanukovych for president. If the residents of the Donbas (including Crimea) had not participated in the 2010-2012 elections, then neither Yanukovych nor the Party of Regions would have had any chance to come to power. Thus, in 2010, the votes between Tymoshenko and Yanukovych would have been distributed as 55.1% against 38.7% (in fact it was 49% against 45.5%), and in 2012, the Party of Regions and the Communist Party of Ukraine together would have received only 34.4% ( and not 43.2%). Similar proportions would have occurred during the elections of 2002-20007.

In other words, without the Donbas, Ukraine would not have had to go through everything that the country has experienced for the past 12 or even all 23 years of independence. After all, it is the voting results in the Donbas for the Party of Regions and the Communist Party that brought them to power. Even after being disillusioned with their former idols, the local residents still did not vote for pro-European and pro-Ukrainian forces but simply boycotted the polls (out of 4.1 million that voted in 2010, only 3 million voted in 2013).

In other words, without the Donbas, Ukraine would not have had to go through everything that the country has experienced for the past 12 or even all 23 years of independence. After all, it is the voting results in the Donbas for the Party of Regions and the Communist Party that brought them to power. Even after being disillusioned with their former idols, the local residents still did not vote for pro-European and pro-Ukrainian forces but simply boycotted the polls (out of 4.1 million that voted in 2010, only 3 million voted in 2013).

Even in the economic sphere, the Donbas is in no way an economic engine for Ukraine or a particularly promising region for the medium term. Its current specialization consists of the old and extremely energy intensive steel industry, the coal industry, which is unprofitable due to the high cost of extraction, and the heavy machine industry that is not competitive on the global market. On top of everything, the region has inflated employment in almost all industries, which in the future will mean chronic unemployment and social problems due to the closure of unprofitable production.

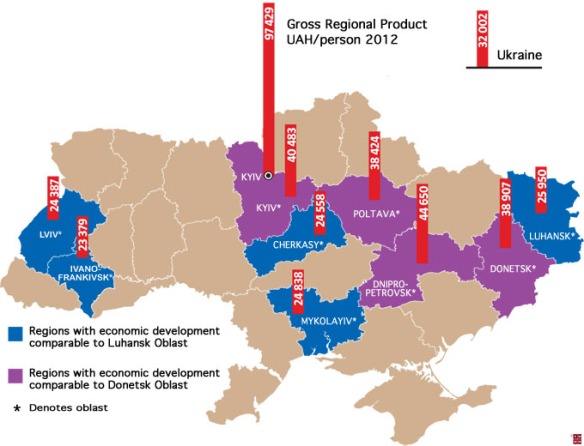

The argument that the Donbas feeds Ukraine and maintains a higher standard of living at the cost of its own citizens is an outright lie. Its share of exports in recent years did represent almost a quarter of the country's total, but it is decreasing. However, the gross regional product (GRP) of the region represents only 16.3% of the national figure (without Crimea and Sevastopol), which is comparable to its share of the population. The per capita GRP in the Donetsk Oblast is slightly higher than the national average, and in Luhansk it is significantly lower when compared to other regions. In 2012, the GRP of the Donetsk Oblast was lower than in the Dnipropetrovsk and Kyiv oblasts (without the city of Kyiv) and comparable to the figure for the Poltava Oblast. In the Luhansk Oblast, it was equal to Cherkasy, Lviv, Ivanofrankivsk and Mykolayiv oblasts and slightly higher when compared to Kirovohrad and Chernihiv oblasts.

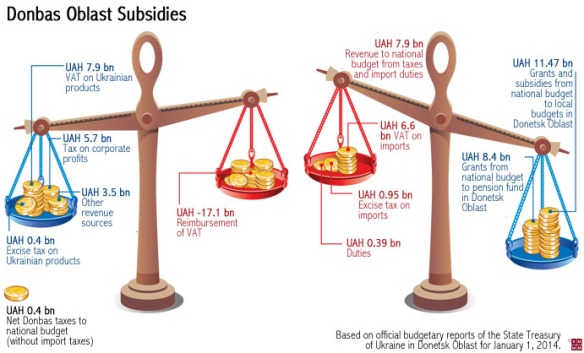

At the same time, the ratio of the average wage in the Donbas and the rest of Ukraine is better that the GRP per capita. And the total revenues to the state budget of Ukraine from the Donbas Oblast (excluding taxes on imported products cleared on its territory) in 2013 represented only UAH 404.6 million (!) As for the taxes on imports (duties, excise taxes and VAT), then their collection in the Donetsk Oblast last year totaled UAH 7.94 bn, and 95% formed the net proceeds from the region to the state budget. However, first of all, this oblast is a border state and many of goods that go through customs here are then sold in other oblasts (therefore such taxes and duties cannot correctly be considered as belonging the region where they cleared). Secondly, in 2013 the amount of subsidies from the state treasury in local budgets and regional offices for the pension fund amounted to UAH 19.83 bn, which is 2.5 times greater than all the taxes collected on imports.

Thus, the direct state subsidies to Donetsk alone exceeded $1.5 bn. Another $100 million of last year's revenues to local budgets came from income taxes on the salaries of miners and soldiers. Both categories of taxpayers are totally dependent on government subsidies (miners) and direct payments (military) from the state treasury. An even greater dependence to the grants from Kyiv can be observed in the Luhansk Oblast, because their own revenues to the budgets at all levels are much lower. Perhaps, for this reason, the main office of the State Treasury, the Pension Fund of Ukraine, and the Ministry of Revenues in the birthplace of Oleksandr Yefremov (Party of Regions leader, born in Luhansk -- Ed.) for a long time has not even published detailed data on the structure of revenues and expenditures of local and state budgets in the region, as well as the pension fund ( in contrast to their colleagues in Donetsk).

Donbas is significantly different from the rest of the southeast regions. The survey conducted April 10-15 by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) captures the distinct differences between them. Yes, the greatest number opposing the idea of separating their land and joining it with Russia among all the southern and eastern oblasts are in Mykolayiv (85.4%), Kherson (84.6%) and Dnipropetrovsk (84.1%) oblasts. In the Kharkiv oblast the number is 65.6%, and in the Donbas barely over half (in Donetsk - 52.2%. in Luhansk 51.9%). Only in Donbas is there a clear majority for the Customs Union - 72.5% in Donetsk and 64.3% in Luhansk. In Dnipropetrovsk, Mykolayiv and Kherson oblasts, there is a significant majority of supporters for Ukraine's integration with Europe over those who support the Customs Union with Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. However, there is still a high percentage of undecideds.

The gap in the perception of reality in a number of other indicators also provides many reasons for discussing the South on the one hand and the Donbas on the other (views similar to those in Donbas are expressed only in the Kharkiv Oblast and to a lesser extent in the Odesa Oblast). However, in the case of these two oblasts, there is significant internal heterogeneity. Only in the Donbas is there a majority of people who believe that Moscow is honestly protecting the interests of Russian-speaking citizens of the Southeast. In the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, 33.4-43.4% of those polled support, in one way or another, the possible deployment of Russian armies in Ukraine. In the Donetsk oblast, 44.8%, and in Luhansk, 42.7%, declared that they in some fashion support the possible annexation of the regions by Russia. The share of the population that said that, in the event of invasion, it would go to the Russian side or would welcome them is much higher than the percentage that would be willing to put up armed resistance. For comparison, in other southern and eastern regions there is a 27 point preponderance (except for the Kharkiv Oblast) of those who are ready to engage in armed struggle with the intruder over those who would support his aggressive actions.

The limits of "compromise"

It is this Donbas that is a part of Ukraine and a burden that the country could have carried longer, taking steps for its modernization and integration with the rest of the regions (which has not been done since independence). However, if the result of the "compromise" with the regional elites is an agreement for going backward -- further "donbasisation" of the entire country, thereby imposing on it the vision of development that prevails in the eastern region -- then this kind of price is not acceptable. The danger is magnified by the fact that by making concessions to the separatists because of the desire to hold on to the Donbas, the central government will agree to extend the budgetary and administrative autonomy and to give official status to the Russian language in all the southeastern regions -- especially in those where the prospects of pro-Russian separatists are much weaker now, but which, after concessions, may increase dramatically.

Preserving the privileged status of the Russian language, already the dominant language in the Ukrainian information space, for half of the country under the openly far-fetched pretext that the rights of the Russian-speaking population must be protected will mean the eventual displacement of the Ukrainian language in the southern and eastern regions and its weakening nationwide. For the primarily Ukrainian-speaking rural areas in the Southeast (which comprise the greater portion of territory in all its oblasts, except for the Donbas), this will mean the imposition of the official status of the Russian language, thus actually resuming Russification, only now on the level of state policy. Since the concept of the "Russian World" is based specifically on the expansion of the Russian language, this will only strengthen Moscow's claims to Ukrainian territory. After this, the pro-Russian part of the population will hardly become less Russian-speaking. Instead, in 20-30 years, the ratio of Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking inhabitants in these regions will resemble present-day Donbas, with all the resulting consequences.

Decentralization, even without federalization, threatens the central government with the complete loss of control over the regions. Henceforth, in many of them ( and not necessarily only in the South and East) this vacuum will be filled by Russia, which will move to de facto direct contacts with the oblast authorities. The bag of tricks available to influence a given region and bring a chosen "elected governor" to power is more numerous than what can be done on a nationwide scale. However, Kyiv will no longer be opposed by marginal street thug separatists and armed saboteurs, but by legitimately formed authorities of this or that country, as was the case recently in Crimea. The formal basis for such separatism will be based (and Moscow and the local anti-central forces don't even hide it) on the likelihood of European and Euro-Atlantic integration of Ukraine, the protection of the Ukrainian-speaking population in the southern and eastern oblasts against discrimination, the integration of the residents of those oblasts in one humanitarian space, and the protection from the influence of the propaganda of Russian media. That way, individual regions will actually gain the right to veto the adoption of any strategic decisions regarding the development of the country.

The example of the Czech Republic and Slovakia demonstrated that a peaceful separation is much better that being forced to coexist, as in Bosnia and Herzegovina. If it becomes impossible to stabilize the situation in the Donbas without concessions to the regions that conflict with the normal functioning of the state, then perhaps it is better to hold a referendum to determine if the residents are willing to step into the future with the rest of the country. However, this must be carried out by commissions formed by the Central Election Committee of Ukraine and not by "green men" as in Crimea. If the residents do not agree, then they should be given the option for self-determination.

A positive example

In the early 1990s, the extensive negotiations on the new distribution of powers between the federal center and the republican authorities of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, which started after the Velvet Revolution of 1989, stalled. The Czechs and the Slovaks could not agree on changes to the Constitution. The Czech Republic sought to "return to Europe" and actively carry out market reforms, while Slovakia feared this would bring about significant unemployment and a sharp decline in living standards. The Slovaks supported at most a loose confederation, and the Czechs a strong federation. The division of Czechoslovakia took place despite the fact that it was not sought either by most Slovaks or Czechs (among Slovaks, 37% were "for"; among Czechs, 36%), but it immediately improved relations between the two nations, and the two former parts of one country ended their conflicts. Slovakia for a time went its own way -- until 1998 its prime minister was the authoritarian and corrupt Vladimir Meciar. Privatization was carried out slowly and with significant violations: many companies fell into the hands of local government officials and functionaries of the ruling party.

Unlike the Czech Republic, Slovakia has not carried out market reforms. The country has not participated in the process of active rapprochement with the EU and NATO. Instead, for a while, it continued to flirt with Moscow. However, after the defeat of Meciar in the 1998 elections, Bratislava began to catch up with the more successful Prague on the road to reform and joined the European Union and NATO.

By Oleksandr Kramar, Ukrainian Week, May 1, 2014

Translated and edited by Anna Mostovych

Original text: http://tyzhden.ua/Politics/108355