by Artyom Krechetnikov, BBC Russia, Moscow

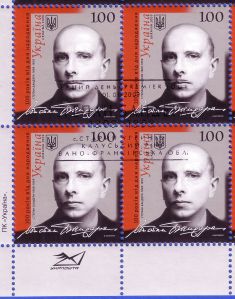

The figure of Stepan Bandera is once again in the spotlight, in connection with the revolutionary developments in Ukraine. Moscow commentators and participants of pro-Russian demonstrations in Crimea call the new government of Ukraine “Banderites” after Stepan Bandera, portraying him as the devil incarnate.

In the estimations of observers, the followers of of the leader of OUN/UPA constitute only one minute segment of the “Orange” movement, but they attract a lot of attention because of their radicalism and excess. In real politics, they do not have any chance of affecting the policies of the government. This is just a scare tactic meant to discredit the proponents of European Orientation.

(The uninformed often say “Benderites” instead of “Banderites”, perhaps because of a subconscious association with Ostap Bender – a fictional character from the novel “The Twelve Chairs” by Soviet authors Ilya and Yevgeni Petrov).

As for Stepan Bandera himself, his legacy is a tangle of truths, half-truths, and myths.

Myth 1 – Bandera was Hitler’s puppet.

The Germans released Bandera from the Polish prison where he had been serving a life sentence for organizing the assassination of Bronislaw Peratsky, Minister of Internal Affairs of Poland.

However, Bandera continued to state publicly that Ukrainians must rely solely on themselves, since no one else was interested in an independent Ukraine, and that any collaboration with Berlin would only be a tactical and temporary necessity.

For this reason, he parted ways with the pro-German official leader of OUN [Organization of Ukrainian Nationals], Andriy Melnyk, who, in contrast with Bandera, is not celebrated by contemporary Ukrainian nationalists.

In February of 1940, the OUN organization split into two wings, named OUN (B) and OUN (M).

In the spring of 1941, OUN (B) created a Ukrainian legion in Poland consisting of 800 men grouped into two battalions, “Nachtigall” and “Roland.” This process was conducted by Yaroslav Stetsko, Mykola Lebed and Roman Shukhevych. Bandera did not participate directly, but it is difficult to imagine that his closest associates acted without his consent.

On the German side, the formation of these battalions was controlled by the Abwehr [German intelligence service]. Admiral Canaris realized Bandera’s men were difficult, but saw them as men of action. According to some sources, he found it useful to support an OUN state, while pretty much offering Bandera and his associates only vague promises.

On the night of June 30, 1941, the “Nachtigall” battalion entered Lviv along with other Wehrmacht divisions. On the same day, Bandera’s allies, headed by Stetsko, gathered at the Lviv Opera House to proclaim the “Act of Revival of the Ukrainian State”.

Lev Shankovsky, OUN historian and also an active participant, later wrote that his organization “was prepared to collaborate with Germany in the common struggle against Moscow” – but only if Ukrainian independence was recognized.

However, Hitler was furious and gave orders to “crush anyone who empowers this Slavic trash.”

Bandera was arrested in Krakow on July 5th and imprisoned in the concentration camp in Sachsenhausen, spending more than three years in solitary confinement – actually, in a special block for “political persons.”

In his novel “The Third Card”, Soviet author Yulian Semenov portrayed this as a German Secret Service operation with the long term aim of creating credibility for Bandera in the eyes of Ukrainians – but there is no evidence for this.

Moreover, Hitler’s position towards any kind of Slavic statehood is well known. In the views of many historians, the leaders of the SD [Sicherheitsdienst, the intelligence division of the Nazi SS] “pulled the wool over his eyes” in order to strike a blow against their competition in the Abwehr.

In their propaganda leaflets, the Germans called Bandera an agent of Stalin. OUN (B) and the newly formed (1942) Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) were outlawed, but they maintained an informal truce with the Germans.

With the defeated Reich grasping at every straw, on September 25 1944 the German authorities freed Bandera, brought him to Berlin, and offered their cooperation. Instead, Bandera insisted on the precondition that they recognize the “Act of Revival”. No agreement was concluded, and Bandera remained in indeterminate status on German territory until the end of the war.

Myth 2 – “Nachtigall” Battalion organized a pogrom against Poles and Jews in Lviv.

According to the conclusions of a government commission for the study of the OUN and UPA, created in 1997 by the order of Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, the murders of Jews, Polish intelligentsia, and Soviet sympathizers in the first days of the occupation of Lviv, known as the “Slaughter of the Lviv Professors” (Lviv Civilian Massacre), were all the work of the German SD and a nationally-oriented unorganized mob.

While one might suspect official Ukrainian historians of not being objective, we do know that immediately following the proclamation of the “Act of Revival”, “Nachtigall” personnel were given a week off, and their German advising officer, Theodor Oberländer, was demoted and called back to Prague.

Several investigators have not ruled out the possibility that some of the pogrom participants might have been “Nachtigall” soldiers in civilian clothes.

The version placing the blame on “Nachtigall” was manufactured by the Soviet Union in 1960 and was directed mainly against Oberländer, who at that time was Minister of Displaced Persons in the government of Konrad Adenauer.

On the eve of abandoning Lviv, the NKVD [People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the Soviet Union] shot to death 2,466 inmates of the local prison. Similar mass executions occurred in other Western Ukrainian cities. In Drohobych, there were 1,101 “category one losses;” in Stanislav (now Ivano-Frankivsk), 1000; in Ternopil, 674; and in Rivne, 230.

Roman Shukhevych’s brother was one of those executed.

“Because this occurred while we were retreating under enemy fire, the prison staff did not always have time to carefully bury and conceal the corpses,” testified the NKVD Ukrainian prison chief, A. Filippov, in Moscow on July 12.

The stench of bodies decomposing in the summer heat was so strong that Germans working on the premises of the Lviv prison wore gas masks. The public was immediately granted access, which to a large extent provoked the pogrom.

Goebbels shared these horrific findings with the press in neutral countries. This information became graphically imprinted in the eyes of world opinion.

In the view of a number of historians, the USSR authorities decided to lump their own atrocities with the Nazis’, and blame them all on “Nachtigall”.

Myth 3 – The Banderites and the SS Division “Galicia” were one and the same.

The “Galicia” Division, which was formed from local volunteers in April 1943 by the German occupants, had no connection with OUN/UPA. Attempts to bring Bandera and his followers to the Nuremberg Tribunal regarding the SS were calculated only for the benefit of the uninformed.

“Galicia” was a part of the Waffen SS and was assigned only for the front lines.

In July 1944 the division was defeated by the Red Army near Brody. The Germans pulled its tattered remnants to the rear, only to use them later against Slovak and Yugoslav partisans.

In February 1944, one of its regiments participated in the destruction of the Polish villages of Podkamen and Huta Penyatska, where 800 more of their members were killed.

In the final phase of the war, the division became part of the 4th Panzer Corps SS, which was active in Austria.

On April 24, 1945, Berlin’s puppet “Ukrainian National Committee”, headed by Pavlo Shandruk, claimed authority over the “Galicia” Division, but this had no practical implications. On German maps, the division functioned as a German unit until the end of the war.

Between May 8 and 11, the “Galicia” Division surrendered to the Allies and took no part in postwar combat in Western Ukraine.

Regarding the ultimate fate of “Nachtigall” and “Roland”, the Germans incorporated them into the 201st Defense Battalion which reported to the army, not the SS. The battalion spent about nine months fighting partisans in Belarus.

In autumn of 1942, because of the German government’s reluctance to recognize the sovereignty of Ukraine, [Ukrainian] personnel in the 201st Defense Battalion refused to renew their contracts and were sent home. Commander Roman Shukhevych was released after interrogation by the Gestapo. In 1944 many of them, including Shukhevych, joined the ranks of the anti-Soviet underground.

Myth 4 – West German intelligence agents murdered Bandera.

On October 15, 1959, KGB agent Bohdan Stashynskiy met Bandera in the hallway of his apartment building in Munich and shot him with a special pistol ampule packed with potassium cyanide. OUN security forces and West German police had foiled four previous attempts on the life of the nationalist leader. In a secret decree, Stashynskiy was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

The Soviet Union laid the blame for Bandera’s assassination on the German Special Service, composing an elaborate story that he possessed some compromising materials about Oberländer and had tried to blackmail him.

Two years later Stashynskiy surrendered to the German Special Service on his own recognizance, and was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Because of the growing international scandal, Khrushchev disbanded the KGB’s special section for political assassination, yet Moscow continued to officially deny any involvement in the death of Bandera up until the era of perestroika.

Mirror images of each other

According to “An Inquiry regarding the Number of Soviet Citizens who perished at the hands of OUN bandits during the period 1944-1953,” signed on April 17, 1973 by Ukraine’s KGB head Vitaliy Fedorchuk, the number of victims of the Banderite partisans amounted to 30,676 people, including 8250 military and security forces.

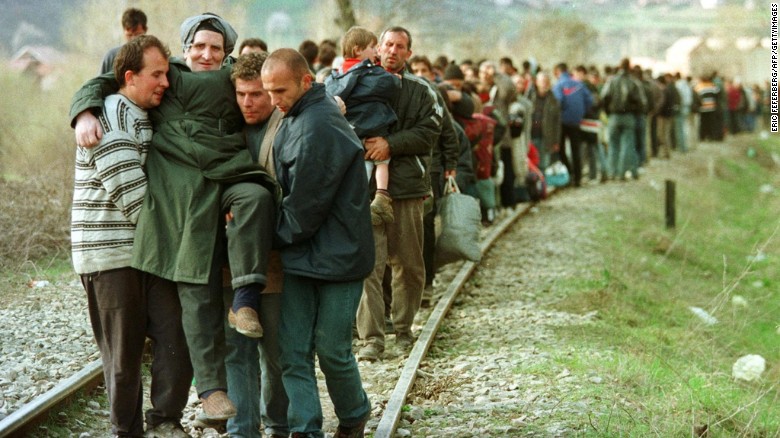

According to the May 26, 1953 Classified Decree of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, “Questions regarding the western regions of the Ukrainian SSR” – their own [Soviet] authorities had killed 153,000 people, sent 134,000 to the Gulag, and deported 203,000 during the same period. Every third or fourth family in Ukraine was affected.

Both sides exhibited extreme cruelty.

There are documented cases of the OUN executing prisoners by tying their legs to bent trees and tearing their bodies apart. The Communist author Yaroslav Halan was hacked to death with a Hutsul hatchet in his home. They murdered people from other areas of the USSR sent by the Soviet government to work in their region. These included teachers and medics dubbed “Easterners” by the OUN members.

For their part, the Soviet authorities hung partisans and guerrillas in city squares, leaving the corpses plainly visible in order to catch anyone trying to remove the bodies for burial. To turn the populace against the OUN, special groups of MGB [Ministry for State Security of Soviet Union, precursor to the KGB] pretended to be OUN members and went to remote villages and hamlets, where they murdered people and plundered their farmhouses.

In “One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich,” Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote about a Western Ukrainian teenager with the code name “Hopchyk” who was “sentenced like an adult for carrying milk to the Banderites in the forest.”

In the opinion of independent historians, Bandera was a radical nationalist by conviction and a terrorist in his methods. Had he been able to create and lead the Ukrainian state, it would certainly not have been liberal and democratic. If Ukraine dreams of a European future, then Bandera is not the figure who should be displayed on its shield.

On the other hand, Stalin and [Chief of Soviet Secret Police] Dzherzhinsky were far greater criminals – with more victims, at any rate. If some Russians can openly praise them without incurring any repercussions from society or the state, then why can’t some Ukrainians justify Bandera?

by Artyom Krechetnikov, BBC Russia, Moscow

http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/russia/2014/02/140227_bandera_myths.shtml

Translated by Anna Palagina and Adrian Bryttan

Edited by Robin Rohrback and Adrian Bryttan