The process was led by the new State institution, the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation (UCF), launched in 2017. Since then tectonic changes for Ukrainian culture — in the broadest sense of the word – have begun. The foundation has supported not only individual projects but has also provided institutional support for initiatives. The range has been wide, including education, research, and book publishing, as well as projects making culture popular.

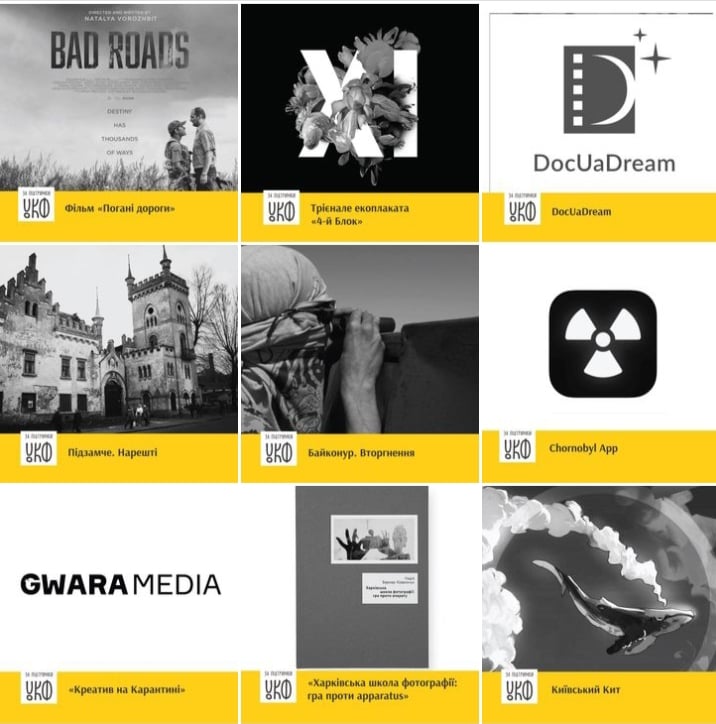

Among the most recent projects supported by the UCF are:

The film Bad Roads by Natalya Vorozhbit which tells the story of war-torn roads leading to and from the war in eastern Ukraine. The film was awarded at the Venice Film Festival, one of the world’s oldest and most prestigious cinema events.

International Triennial the 4th Block, a festival for unique designers of eco posters and social projects.

DocUaDream, the School of Documentary and Media for teenagers from Donbas which helps children of war take their first steps in documentary filmmaking, photography, and journalism.

@pidzamche.nareshti. The initiative which united activists and citizens of the district Pidzamche in Lviv.

Baikonur. Invasion. A documentary about two Ukrainian researchers sneaking onto the classified territory of the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to watch the launch of the Soyuz rocket.

@chernobylapp The first mobile app depicting the Chornobyl nuclear disaster, providing a virtual tour of Chornobyl to learn more about the tragedy.

Creativity on Quarantine, a series of publications about the success of cultural initiatives during the COVID pandemic which have not been hampered by the quarantine.

Monograph on the Kharkiv School of Photography titled “Game Against the Apparatus.” Author Nadia Kovalchuk is a longtime supporter of the Kharkiv School of Photography, regarded as a unique phenomenon of Ukrainian culture.

Kyivwhale, an ecological project creating the largest media sculpture from recycled plastic. The project demonstrates that plastic is not trash but can be used as a resource for many purposes.

To understand the scale of changes in Ukraine’s cultural sphere since the Euromaidan Revolution and in particular the evolution since the establishment of the UCF, a brief review of previous periods is warranted.

How Soviet Union policy totally distorted Ukrainian culture

Initially, after Ukraine declared Independence, the importance of cultural policy was underestimated. So were the cultural figures. Their only option was to follow the official party line or to be independent and conceal their work deep underground. This manner was left from the Soviet Union. During the Soviet era, cultural policy served the purpose of propaganda. To veer from this path, artists of all fields would place themselves in serious danger by the State apparatus.

In different periods, the level of threat by the Soviet State for independent writers, poets, artists, performers, and many others was severe. Some cultural figures managed to subtly integrate symbolic narratives into their works. However, it was impossible to do so on the issue of national identity. The apparatus was constantly monitoring for any hint of national independence or freedom of thought.

Dozens of prominent cultural figures were subject to harsh measures of repression during Stalin’s Great Terror. In Ukraine, from the 1920s to the 1930s, an entire generation of artists was either exiled to Siberia or liquidated.

In place of an authentic living culture, the Soviet propaganda machine substituted an artificial pejorative form. This form is often referred to as sharovarshchyna (from the term for Ukrainian men’s folk pants sharovary). The intent was to portray Ukrainian identity as primitive and representative of crude peasantry.

How culture gained freedom, but no support

After the collapse of the USSR, Ukrainian culture experienced freedom. However, having been fettered for decades, the country’s cultural identity lacked vision, cohesion and strategy and, what is most crucial, money.

Meanwhile, Sharovarshyna was still imprinted on a nationwide scale.

With the advent of the global economic crisis of the 1990s, cultural policy was among the least vital concerns on the public agenda. All categories of artistic creation were left far behind and had no material basis for development.

Cultural support was an element of the EU Eastern Partnership initiative launched in 2009. For the first time, Ukrainian cultural institutions were granted access to the partnership’s grant allocations. Looking back, Kateryna Botanova, independent art curator and critic, describes how during the first three years of the program’s onset, attempts to establish a partnership with the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture were unsuccessful.

“The mandate of the program to help and support cultural policy reforms in Ukraine has been effectively covered in dust, in part due to the sincere misunderstanding by domestic cultural officials of what this cultural policy is and why it is needed.”

Botanova summarizes the dilemma in simple terms, saying that as of 2010, the cultural sphere in Ukraine has clearly been divided along two lines – State and Non-State (official and non-official). The State (official) line that has controlled the funds in the State’s budget has been stymied by a large-scale network of corrupt cultural institutions inherited from the Soviebt Union. While the non-State (non-official) line has been led by oligarchs.

Cultural journalist Kateryna Stukalova describes the period in much the same way, saying that in the 1990s it became clear to cultural figures that interaction with simulated State institutions was meaningless and ineffective. Meanwhile, the consumer market could not support the existence of artists, even for mere survival.

“The inevitable drift of Ukrainian art into the arms of oligarchic clans and its incorporation into a new quasi-feudal social structure began.”

Some of the oligarch projects were and still are quite successful; for example, the renowned PinchukArtCenter, an international modern arts center. Founded in 2006, the center is a project of the Victor Pinchuk Foundation. As its name connotes, the foundation was established by media magnate Viktor Pinchuk, among the richest Ukrainian oligarchs.

At the same time, with some exceptions, the Ukrainian cultural field has become apolitical.

“As long as contemporary art existed in its parallel world, without making any articulated demands from the State, demonstrating self-sufficiency and almost not commenting on political processes in artistic language, the State has learned to use its autonomy and lack of claims to budgetary resources. There were two parallel worlds — the modern art process with its own resources and survival strategies and the State apparatus — a decorative facade that simulated ‘culture management’ and is guided by completely inefficient, disconnected from reality, and opaque principles of activity,” Stukanova wrote.

Among the prominent cultural events of the first decade of the 2000s, Botanova mentions the formation of a new staff complement for the Kyiv Arsenal National Art and Culture complex. The new team’s goal was to make the center the Ukrainian Louvre. The opening of the art center Isolation in Donetsk was also an important event. The center was moved to Kyiv with the onset of the war in Donbas. The original center in Donetsk has been turned into a concentration camp of the Russia-backed, self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR).

- Read also: Three warders who tortured prisoners in occupied Donbas “concentration camp” ID’d as Russian citizens

Botanova points to another cultural achievement supported by an oligarch — Rinat Akhmetov, indisputably the richest in Ukraine. The country’s first and only grant program to support iZ culture was established by the Rinat Akhmetov’s Foundation.

In addition to the above, in recent years Ukrainian artists have had opportunities to carry out networking with other European artists and arts facilities through funding by the EU’s Eastern Partnership Culture Program.

Botanova names the year 2010 as the last before the fall into the political quagmire of the runaway president Viktor Yanukovych.

And then the Euromaidan Revolution erupted. Together with social-political changes, the revolution raised cultural policy to the level of national importance.

Development after the Euromaidan Revolution

First of all, during the protests, cultural figures by far were not silent and at some points led the process.

When the revolution ended in February 2014, it became clear that the country, as well as the nation, could not survive without a cultural policy and common narratives. It also became clear that the old models no longer worked.

The approach was for various cultural activists to unite in a Cultural Assembly. They tried to introduce reforms to the Ministry of Culture. When this attempt failed, they started demanding its liquidation, replacing it with different corresponding agencies.

The plan did not work, and the ministry exists to this day. However, there were some positive outcomes. Many competent representatives of the cultural field saw opportunities to develop cultural policy. As well, new agencies did start to appear — among them, the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, the Ukrainian Book Institute, the Ukrainian Institute, and the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.

Step by step, Ukrainian culture started to make its way through the thorns of bureaucracy and the weeds of stereotypes. Sharovarshyna was not totally eliminated, but movement in the right direction definitely began.

The role of the UCF in this process has become crucial. Simply because it exists, the institution represents significant changes to the old ineffective mechanisms.

For the first time in Ukraine’s Independence, because of the UCF, the State has provided opportunities for grassroots initiatives to form the cultural agenda. Moreover, the development and formation of common values in civil society has become a priority for the State.

The first results and disappointments

Some of the projects supported by UCF.

Through a competitive selection process, the UCF supports projects that contribute to its goals:

- Providing a favourable environment for the development of intellectual and spiritual potential of individuals and society;

- Ensuring wide access for citizens to national cultural heritage;

- Supporting cultural diversity; and

- Encouraging integration of Ukrainian culture into the world cultural space.

During the three years since its inception, the UCF has supported 1,685 different projects amounting to UAH 1.5 bn ($54 mn). Summarizing the work, Yuliya Fediv, the first executive director of the UCF, noted that the need for continued State funding is significant.

According to Fediv, during the last three years, the foundation has received 6,386 applications from numerous organizations proposing an entire spectrum of projects. In 2018, there were 716 applications; in 2019 there were 2,059; and in 2020 there were 3,611.

The UCF is not ideal and has had its share of scandals, with some related to the allocation of State funds. The most recent controversy has been over the number of known successful initiatives that were rejected in funding after the appointment of the new UCF’s management in spring 2021.

“Our delight over the new transparent cultural institution that was finally opened in Ukraine was short-lived,” says the statement released by the film festival Kharkiv MeetDocs after it was rejected in funding this year.

According to the statement, the total audience of the festival is 4,000,000 viewers, this year it received 450 points out of 500 possible from UCF, but eventually was not even accepted to the negotiation procedure.

Similar things have happened to a number of known initiatives. Among them Mute Nights Festival, 10th Festival of silent cinema and modern music, Dovzhenko Centre, cultural institution keeping Ukraine’s cinema legacy, 5th cinema festival Kyiv Week of Critics, V Forum of Creative Industries, and others.

Soon, it will be visible whether such a recent turn is indeed the beginning of serious problems. However, so far it is clear that the very existence of the UCF has laid the groundwork for the ongoing development of Ukrainian culture. After long years of Soviet oppression and neglect by various governments, culture has finally made it onto the agenda.

Read also:

- New Lviv Museum showcases clandestine avant-garde art outlawed during Soviet era

- Recovering the forgotten names of the Ukrainian avant-garde

- Who’s winning on the Ukraine-Russia historical narrative battlefield?

- A taste of Ukraine’s poetic Renaissance executed by Stalin

- Modernized past: how today’s Ukrainian culture combines tradition and modernity