The tsarist government decided to subjugate the remaining troops. After using the remaining Zaporizhzhian Cossacks in the Russo-Turkish War (1787-1792), the Russian government began resettling them on the territories recaptured from the Turks - between the Kuban River and the Sea of Azov, where the Nogai Tatars, who had been exterminated by Russian troops, had previously roamed. On July 2, 1792, Empress Catherine II of Russia issued a decree on the resettlement of Ukrainian Cossacks in this region.

The new land of the Ukrainian Cossacks

Thousands of Ukrainian Cossacks and their families moved to the Kuban region. They formed 40 kurins (units of Zaporizhzhian Cossacks) that were immediately included into the Black Sea Army. Ukrainian Cossacks were well-known for their riotous behaviour and disregard for orders, so the Russian government was more than eager to absorb them into the Black Sea Army as quickly as possible. Their main mission was to protect the borders and frontier regions. The Black Sea Cossack Host also took part in Russian military operations.

The settlers were given a plot of land on 30,000 square kilometres stretching between the Kuban and Yeya Rivers. The main headquarters of the Black Sea Army was located in Katerinodar, founded in 1793 (today’s Krasnodar in the Russian Federation).

The ranks of the Black Sea Cossacks were replenished mainly by Ukrainian Cossacks from Chernihiv and Poltava provinces, Sloboda Cossacks from Kharkiv province, as well as troops from various Ukrainian Cossack Hosts that had been previously abolished, such as the Ust-Dunai, Azov, Buz units and others. The resettlement campaigns took place in 1808–1811, 1820–1821, 1832, and 1848–1849.

The Ukrainian Cossacks of the Kuban lived under difficult conditions. Mortality was high; in order to survive, they were forced to tame the harsh environment of the Kuban region, and their settlements were constantly attacked by the Adyghe, Turks and other Caucasian peoples.

Planned resettlement and incorporation of the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks into the Black Sea Army initiated the first stage of Russification. The next stage came about in 1860, when the Black Sea Cossack Army was integrated into the western divisions of the Caucasus Line Cossack Host, created in 1832, which consisted mainly of Russian soldiers whose mission was to conquer and pacify the Northern Caucasus. This combined army was called the Kuban Cossack Host (Кубанское казачье войско); formed in 1860, this administrative and military unit composed of Kuban Cossacks existed formally until 1918.

Despite targeted Russification of these settlements, many facets of Ukrainian Cossack customs and culture were preserved in the Kuban region. Writer, historian, ethnographer and appointed Otaman of the Black Sea Army Yakiv Kukharenko (1800-1862) vividly described the daily life of the Black Sea Cossacks. In his popular play/operetta - Chornomorsky Pobyt (Black Sea Life) - he chronicles the life of Kuban Cossacks at the end of the 18th century and during their settlement in the Kuban region. In 1878, the operetta was adapted to the stage by Mykhailo Starytsky and presented as Chornomortsi, with music by Mykola Lysenko. Kukharenko also corresponded with many Ukrainian cultural and literary personalities, in particular with Taras Shevchenko.

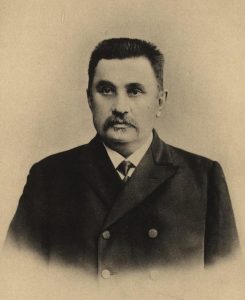

Another prominent figure from the Kuban was Fedir Shcherbyna (1849–1936). He was an eminent statistician, economist, sociologist and historian of the Kuban region, whose scholarly works were highly valued in tsarist Russia. In 1904, he became a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. From 1917 to 1920, Shcherbyna, despite his advanced age, was an active participant of the Ukrainian movement in the Kuban.

In 1920, Shcherbyna emigrated to Prague, where he took part in diverse activities of Ukrainian academic and scientific institutions. He worked as professor at the Ukrainian Academy of Economics in Podebrady and the Ukrainian Free University. In 1924 he became full member of the Shevchenko Scientific Society.

Fedir Shcherbyna also wrote some epic poems, namely Chornomorets (1919) and Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1929). He was buried in Prague. However, in 2008, with complete disregard for his last wishes to be buried in the Kuban and without his family’s permission, Shcherbyna’s ashes were re-buried in Krasnodar, RF with the support of Russian diplomats and the pro-Russian Orthodox Church of the Czech and Slovak Lands. Once again, a famous Ukrainian personality - Fedir Shcherbyna - was appropriated by the Kremlin, thus spreading and enhancing the myth of the “Russkiy mir” (Russian world).

The Kuban Cossacks continued the traditions of the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, spoke Ukrainian and, accordingly, identified themselves as Ukrainians. According to the census conducted in tsarist Russia in 1897, more than 900,000 Ukrainians lived in the Kuban region, accounting for 47.4% of the population. It was the largest ethnic group in the region. In some districts of the Kuban region (Katerynodarsky, Yeisky and Temriutsky), Ukrainians made up the majority of the population.

Rebellion in the Kuban

Following the 1917 February Revolution in Petrograd and World War I, the Russian Empire began to disintegrate. As the Cossack Hosts were basically loyal to the emperor rather than to Russia, the end of the monarchy in March 1917 meant that many Cossacks felt they no longer needed to remain loyal to Russia. When Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, bringing an end to the Romanov dynasty, the Kuban governing council, the Kuban Rada (parliament) in March 1917 proclaimed itself the sole administrative body of the region.

On February 16, 1918, the Kuban Rada proclaimed the independence of the Kuban People’s Republic from Bolshevik Russia. On December 4, 1918, the government changed the name of the region to Kubansky Krai; its territory included Kuban Oblast, the Black Sea and Stavropol provinces, as well as Terek Oblast.

A few days later, the members of the Council voted a resolution to join Ukraine as a federal structure. A delegation from the Kuban, headed by the chairman of its Legislative Council, Mykola Riabovil (1883–1919), visited Kyiv and was received by Hetman of Ukraine Pavlo Skoropadsky. Diplomatic ties were thereby announced between the Kuban People’s Republic and the Ukrainian People’s Republic.

For his part, Hetman Skoropadsky provided some assistance and support to the Cossacks, including weapons and ammunition. However, it was not enough to save the Kuban from the Bolsheviks. Unfortunately, this region was cleared of the Bolsheviks not by the Ukrainian army, but by Anton Denikin’s anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army, which fought for a “united and indivisible” Russia. During the Russian Civil War, the White Army achieved an important victory despite being numerically inferior in manpower and artillery. It resulted in the capture of Katerinodar and Novorossiysk in August 1918 and the conquest of the western part of the Kuban by the White armies. Later in 1918 they took Maykop, Armavir and Stavropol, and extended their authority over the entire Kuban region.

Many Kuban Cossacks served in this army, in particular under General Andriy Shkuro, who was from a Ukrainian Kuban Cossack family. After officially joining Denikin’s White Army, he was appointed commander of the Kuban Cossack Brigade. Shkuro led the Kuban Cossacks to Moscow to liberate Russia from the Bolsheviks, but the Cossack Host suffered many losses and casualties during this campaign. In the meantime, the leadership of Denikin’s Volunteer Army hunted down and persecuted Ukrainian activists in the Kuban. In June 1919, Mykola Ryabovil, one of the main political leaders of the Ukrainian Kuban community, was assassinated by agents of the Volunteer Army. Riabovil’s politically-motivated assassination had great resonance; political organizations and parties rose up in protest, and the Kuban Cossacks began to desert more massively from Denikin’s army.

Denikin’s Volunteer Army, whose leadership was trying to restore the old order - a single and undivided tsarist Russia - eventually lost support and was defeated by the Bolsheviks. In the spring of 1920, the Kuban fell to the Bolsheviks, and the Kuban People’s Republic with its pro-Ukrainian orientation ceased to exist. The Host was finally dissolved by the Bolsheviks, and many Cossacks emigrated to Western Europe, where its leaders hoped to continue their fight for freedom and find support for their cause among foreign leaders.

Ukrainization in Kuban (1923-1933)

From 1923 to 1933, in order to enhance party institutions and legitimize Soviet rule in Ukraine, the Communist Party brought in a series of measures favouring the Ukrainian language, as well as Ukrainian literature and culture. This period is commonly referred to as the era of “Ukrainization”.

Of course, the Bolshevik regime was opposed to the Kuban becoming part of Soviet Ukraine, but it was forced to agree to Ukrainization in order to stabilize its rule and placate the Ukrainian peasants. According to the 1926 census, Ukrainians made up 66.58% of the population of the Kuban. In total, there were more than 3,100,000 Ukrainians residing in the Kuban region (45.48% of the total population).

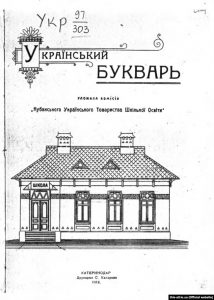

In 1923, two Ukrainian schools were opened in Krasnodar. Over time, schools in the villages and towns of the region, even some technical schools and institutes, began to switch to Ukrainian. Ukrainian textbooks were published in Krasnodar in 1926, and most institutes of higher learning changed the language of instruction to Ukrainian. Ukrainian-language newspapers, journals and radio broadcasts appeared. Administrations switched to Ukrainian and Ukrainian cultural life flourished and spread across the region.

However, the Ukrainization policies of the Kuban were abruptly reversed at the end of 1932. Moscow included the Kuban in the North Caucasus Krai, which made possible the further Russification of the Kuban Cossacks, and the Ukrainian language lost its official status.

The December 14, 1932 publication of the grain procurement resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of People’s Commissars demanded that all official paperwork and publications of the “ukrainized” districts of Kuban be immediately translated into Russian, as the Russian language was “more intelligible for the people of the Kuban”. These measures were followed by Stalin’s man-made famine - the 1933 Holodomor. At the same time, advocates of Ukrainization were persecuted, imprisoned or sent into exile. Schools, offices and administrations were forced to work in Russian. Ukrainian-language press and radio disappeared. Russians from the northern regions were encouraged to settle in depopulated areas of the region. Kuban Ukrainians were henceforth registered as Russians. The local Ukrainian dialect was mocked and labelled as “Cossack chitchat”, just a lesser dialect of the Russian language.

World War II and the years thereafter…

Anti-Bolshevik sentiments persisted and the Kuban continued to resist Soviet rule. As a result, during World War II, many Kuban Ukrainians fought against the Soviets, either integrating the Ukrainian Insurgent Army or the ranks of the German Wehrmacht.

Partisan units continued their struggle for freedom well into the 1940s and 1950s, when the Cossack Insurgent Army (Козача повстанська армія or КОПА) - an analogue to the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) - fought against the Bolshevik army and the Nazi occupation forces.

Meanwhile, the Soviet regime pretended that everything was fine and dandy in the Kuban. In 1949, one of the first Soviet colour films, The Kuban Cossacks, shot at the Mosfilm studio, enjoyed great popularity. It depicts the happy life of people working on collective farms in the Kuban. Record harvests are gathered in the fields, collective farmers are awarded orders and medals, and the tables of Kuban families are laden with food and drink. The Kuban Cossacks, who once fought against the Soviet government, are now peaceful collective farmers working for the good of their socialist homeland. And, of course, they all speak Russian.

It was during those difficult years, from 1927 to 1949, that Ivan Piddubny (1871–1949), a prominent Ukrainian strongman, lived in the Kuban city of Yeisk. He corrected his nationality in his passport, crossing out “Russian” and writing “Ukrainian”. Despite the fact that Piddubny was of Ukrainian origin and considered himself Ukrainian, the Russians tried and are still trying to present him as a “Russian strongman”. Ivan Piddubny died from a heart attack, but undefeated, on August 8, 1949, in the town of Yeisk, Kuban Oblast, RF. He was buried in Yeisk in a park outside the city. A plaque with the following tribute was erected near his grave – “Here lies the Russian bogatyr!”… although Ivan always proclaimed that he was Ukrainian.

Despite strong Russification of the region, the Kuban population managed to preserve and foster the Ukrainian language and traditions. The Kuban Cossack Chorus, which has existed since 1811 and is the oldest choir in Russia, has grown to become one of the leading concert ensembles in Russia. It regularly tours abroad and has appeared in dozens of foreign countries. A significant part of the songs in its repertoire is in Ukrainian.

It is interesting to note that the Krasnodar Philharmonic is named in honour of Ukrainian composer Hryhoriy Ponomarenko, who was born in the village of Morivsk, Chernihiv Oblast, Ukraine in 1921. It was only in 1972 that he moved to the Kuban, where he lived and composed until his death in 1996.

After the fall - 1991

The modern Kuban Cossack Host was re-established after the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991. There were several attempts to create an autonomous republic in the Kuban, but they were unsuccessful. However, in the early 1990s, Ukrainian life, traditions and culture grew and spread across the region, although officially Ukrainians made up a little more than one percent of the population in the region. Ukrainian newspapers, publications and public organizations appeared in the Kuban. Some schools began offering optional courses in the local “lingo”, for which the Ukrainian-language textbook Kozak Mamai was used.

Unfortunately, this Ukrainian movement was not strong enough to impact daily life and resist Moscow’s authoritarian directives. Since the late 1990s, Moscow has carefully controlled the so-called “Cossack revival” in the Kuban and has hastened to impose stereotypes of the “Russkiy mir” on Kuban residents. On its part, Ukraine has done little to support and encourage the declining Ukrainian Diaspora in the region.

Not surprisingly, in 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea and launched the war in the Donbas, many so-called “Kuban Cossacks” went to the Ukrainian Donbas to support the Russian-controlled militants. There were isolated protests against the Russian authorities in the Kuban at that time, and the Kuban People’s Republic was momentarily declared, but it was quickly quashed by the Kremlin.

The history of the Kuban of the 20th century illustrates the tragic history of the ethnocide of a large part of the Ukrainian nation, people who were aware of their Ukrainian identity, but who were brutally Russified and continue to be Russified. As political analyst Paul Goble so aptly says:

“This history does not mean that the Kuban should be annexed to Ukraine any more than the ethnic resettlements, which Stalin sponsored after the Holodomor in the Donbas, mean that that region should be detached from Ukraine. But, what it does mean is that Ukrainian arguments should be taken seriously rather than dismissed out of hand as they all too often are.”

Photo gallery of the Ataman tourist complex near the village of Taman - the first settlement of Ukrainian Cossacks in the Kuban in the late 18th century. The museum complex exhibits Cossack buildings from all over Black Sea Kuban.