“In their New Year's greetings, presidents tell us about GDP growth, lower inflation, 'implementation', 'diversification', and other obscure terms. In general, they convince us that we've started living better..., so very often we just put our TVs on mute during the president's address... Tonight it's going to be different.”

Also, the whole style of the speech was informal and personal, including short comments from ordinary Ukrainian citizens and TV-stars to show that the President is just the same as all Ukrainians.

By content, however, the speech was manipulative and logically erroneous, using emotions and analogies to promote indifference to national identity and national symbols, such as street names and monuments. This provoked outrage from public leaders of different political persuasions.

At the same time, the speech has rekindled a discussion regarding the model of the Ukrainian nation: either ethnic-based or only political. This discussion is especially important as the Russian hybrid war is still ongoing, also in the identity battleground, while a large part of Ukrainian citizens do not identify themselves or share values and attributes of Ukrainian ethnicity.

Zelenskyy’s New Year greeting can be read in English here.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qo7JDweEAYs[/embedyt]

“What is the difference” - the main message of Zelenskyy’s speech

“What is the difference?” was the main message of Zelenskyy’s speech. It was disgraceful for Ukrainians and reportedly praised in Russia. Russian citizens point out that in his speech Zelenskyy made all people equal regardless of national boundaries or political views. For them, it was a radically opposite message to that of Putin, who constantly refers only to those who voted for him and declares others to be enemies.

For Ukrainians, and first of all ethnic Ukrainians (who speak Ukrainian, share Ukrainian culture, history, and values), the message of Zelenskyy was disastrous as it de-facto proposes to make Ukrainian culture in Ukraine only one among other minority cultures, without any special national status. Just a few examples of the messages that Zelenskyy expressed:

- He equates Ukrainian as a “native language” in western Ukraine with Crimean Tatar, Hungarian, and Russian as native languages in some parts of Ukraine, asking “what is the difference” what language one speaks, and eliminating the special attitude to Ukrainian as the national language.

- The speech claims that only economic prosperity matters, while symbols are meaningless. Zelenskyy says about his Ukraine: “Where the name of the street doesn't matter because it is lit and paved. Where it makes no difference, at which monument you're waiting for the girl you love.”

- The speech urges overcoming the distinction between pro-Russian Ukrainian citizens and Ukrainian nationalists to live together in one country as they all are citizens. This statement was especially badly accepted on the background of the still ongoing war with pro-Russian separatists, many of whom were Ukrainian citizens. Such statements also go in line with the Russian narrative that war in Ukraine is a civil war.

- All these and similar statements were packaged in nice words, expressed emotionally, making the speech manipulative. As with the example of monuments, in no way can love for a girl be an argument for indifference over what monument stays on the street. Nonetheless, such speeches work.

In fact, “What’s the difference” recalls a Soviet argument used to russify Ukraine in the 1970s and 1980s. It was simply easier to use Russian as a more popular language worldwide than Ukrainian. “What’s the difference” in reality means “let Russian dominate because it’s not important what language one speaks.”

Two models of Ukrainian nationhood debated after Zelenskyy’s speech

However, not the speech itself is that important, but the public discussion that was triggered by it. The important issue of identity in Ukraine is that two parts of the population have two different visions of what Ukrainian nationhood should be.

The first vision, mostly supported by opposition to Zelenskyy, is that of ethnic-based nation and state, like Poland or Israel. In the constitutional laws of Israel, for example, it is clearly stated that “Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people." Language, cultural identity and history are important and meaningful for this type of nation.

The second vision, supported by so-called progressive pro-European opinion leaders as well as Russian-speaking minorities, is of a political nation, based on the similar rules of the game and common future. Political system and benefits from participation in this system are the glue that unifies the nation in this case. The USA and especially Canada are models of this type.

By no means, simple is the choice between these two ways. On the one hand, the historical fight of Ukrainians for their independence was based on strong ethnic solidarity. Due to such things as Ukrainian songs, language and culture, Ukrainians survived in a totalitarian system as a separate people. Finally, Ukraine is the only place in the world where Ukrainians have a chance to build their nation-state.

Therefore, for a large part of society, it is unacceptable to develop Ukraine as a multi-ethnic society, according to the Canadian model, as it will mean the loss of Ukrainianness in this state. Last but not least, in the context of the Russian hybrid war, ethnic solidarity is what makes Ukrainians strong and unified as well as separate from the Russian nation. Multi-ethnic society in Ukraine with a strong Russian minority, as soon as it obtains legal status, will be vulnerable to Russian aggression that aims at the destruction of the Ukrainian state.

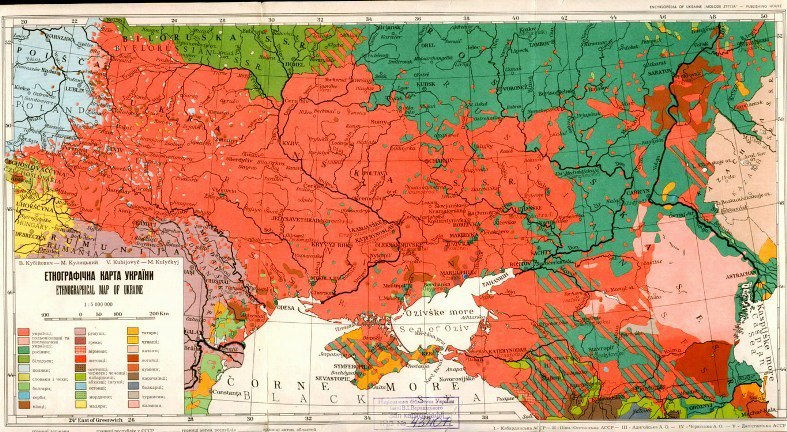

On the other hand, to implement a mono-ethnic ideal in Ukraine, as in Poland or Israel, is not easy. Only in the western part of the country is the population 90% or more Ukrainian. Regarding other oblasts, especially in the southeast, identity became more complex after the two World Wars, Holodomor and Soviet repression. There is a strong Russian minority in the southeast, also Ukraine includes such regions as Bessarabia (south of Odesa oblast) with several ethnic groups or Crimea with huge population of Crimean Tatars some of whom now resettled in non-occupied Ukraine.

Finally, a large part of society in reality still shares a kind of Soviet identity, artificially created since the 1930s. For these people, any ethnicity has small significance, as does language. “What is the difference” is their typical argument, although they mostly speak Russian as more internationally present language and oppose any Ukrainization, interpreting it as backward.

Coming back to Zelenskyy’s speech, the interesting point is that both liberal and conservative intellectuals of Ukrainian society criticized it. For obvious reasons, the speech was directed against an ethnic vision of the Ukrainian nation. Ukrainian nationalists were absolutely outraged. However, many liberals were also dissatisfied. For example, Hennadiy Druzenko, former Government Commissioner for Ethnonational Policy, has been actively promoting the narrative of the “unification of nation” not on the cultural, language or ethnic basement. At the same time, he criticized Zelenskyy’s speech rigorously:

Having rejected Ukrainian cultural identity as the glue that holds Ukrainian society together, Zelenskyy offered nothing in return. He did not call the enemy an enemy. And he offered no vision of a common future. He said nothing about the same rules of the game for everyone.

Zelenskyy as the manifestation of post-Soviet identity in Ukraine

The debates between Ukrainian conservatives and liberals, who indeed exist in public space although not in the form of classical parties, can be long, argumentative and productive, leading to complex and balanced decisions. This was the case with laws on language policy or broadcasting quotas, for example.

Read also: Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

Zelenskyy’s speech, however, was neither conservative nor liberal in the modern sense. Rather, it was the manifestation of post-soviet identity in Ukraine. And this is nothing unexpected.

Larysa Masenko, professor of Philology at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, claims that Zelenskyy is the representative of neither Ukrainian nor Russian people but Soviet, just as many other Ukrainian citizens:

At the time of the collapse of the USSR, the totalitarian project of creating a single "Soviet people" based on the Russian language from the multiethnic population achieved considerable success in Ukraine. Soviet social engineering has succeeded in forming within the Ukrainian community a fairly numerous layer of denationalized "ordinary Soviet people"... Volodymyr Zelenskyy is a representative of this assimilated part of the Ukrainian society. This is evidenced by all his creativity – both the comedic production of his studio Kvartal 95 and the films and series of its production, much of which was created in collaboration with Moscow.

That is why Zelenskyy says in his speech what Ukrainians disparagingly name a “sausage rhetoric” - that name of a street doesn’t matter if it’s paved.

The strength of this Soviet or post-Soviet identity in Ukraine is exploited by Russian propaganda and chauvinism, Larysa Masenko claims. As evidence, she provides citations from Zakhar Prilepin’s article “Ukrainians don’t exist? What a pity”:

The Ukrainian language exists. Ukraine as a state is also there, there is a Ukrainian idea, a yellow-blue flag, a trident [national emblem], Bandera with Petliura and Mazepa [Ukrainian military leaders], Shevchenko's Kobzar, Ukrainian nationalism, and Ukrainian literature, but there is no such people and never has been.

Yet more explanatory were thoughts by Russian journalist Oleksandr Chalenko at the web-page Russian idea:

Yes, there is the Ukrainian language, the Ukrainian alphabet, Ukrainian literature, embroidered shirts, Ukrainian “history”, Ukrainian national “heroes”. There are millions of people who sincerely consider themselves “Ukrainians”, but nevertheless no “Ukrainians” exist in nature. It’s just that all these “movas” [Ukrainian language] and “Ukrainian literature” exist autonomously from those people who live in the territory of modern Ukraine, and have no contact with them in any way. Why don't they touch? Yes, because approximately 90% of Ukrainian citizens are Russian people. They don’t use any “mova”, and generally nothing “Ukrainian” in their everyday life.

Of course, such statements are an exaggeration. However, post-Soviet people sharing post-Soviet identity are indeed numerous in Ukraine and give Russian ideologists reasons to use such statements in their propaganda.

Larysa Masenko in her article also drives attention to the scene from the comic show of Kvartal 95, Zelenskyy’s former studio, which was shown just after presidential speech. The show, as usual, was in Russian and consisted of a parody on a popular Ukrainian folk song. “The music is beautiful, the words are legible, performed for the first time soberly,” - the comment to the song stated.

Ukrainians were portrayed as outward and constantly drunk. That show is broadcasted in the most popular TV-channel 1+1. It was watched by one-quarter of the whole TV audience on New Year’s Eve.

Read more:

- Ukraine’s main challenge: to solve its identity crisis

- Ukrainian writer & publisher: Language is the most important marker of national identity

- Euromaidan, rebirth of the Ukrainian nation, and the German debate on Ukraine’s national identity

- Can Ukraine escape the post-communist trap?

- Russian as a minority language in Ukraine vs Russian as Putin’s weapon: Is there a compromise?

- Ukraine creates free online courses of Ukrainian language for foreigners

- Should Ukraine take over the Russian language? Scrutinizing Prof. Snyder’s arguments

- Russian as a minority language in Ukraine vs Russian as Putin’s weapon