“Of course, we want the Russian-speaking population, not only in the Donbas but in all Ukraine, to enjoy equal democratic rights. I would like to draw your attention to the fact that 38% of citizens of the country consider themselves Russian-speaking in Ukraine. And from next year, as we know, all Russian schools will be transformed into Ukrainian…”

At the same time, Artem Miroshnychenko, a pro-Ukrainian civil activist was killed by gangsters in government-controlled Donbas after his Ukrainian language triggered their aggression. Meanwhile, the Venice Commission praised Ukraine’s new education law that protects the Ukrainian language in schools but criticized the absence of a law on the protection of minority languages.

All this leads to the question, whether there is any balanced decision for language controversy in Ukraine and what will be the impact of the planned introduction of Ukrainian as the language of instruction in the last 200 Russian-language schools

Read also: Zelenskyy’s first Normandy and the illusion of progress

How the murder of Artem Miroshnychenko illustrates the language issue in Ukraine

The recent murder of Artem Miroshnychenko in the Donbas town of Bakhmut provoked a new wave of discussion regarding language laws in Ukraine. People started sharing in social media posts saying “I will tell you what is the difference. Artem Miroshnychenko was killed for his language”, answering in that way the typical argument against any language policy that sounds like “what is the difference [what language one speaks]”

Although the Ukrainian language as the trigger for the murder of Artem was not yet proved by the court and only reported by an anonymous witness who did not want to speak publicly, the political views of Artem, his firm pro-Ukrainian position and Ukrainian language made him well-known in his mostly Russian-speaking town Bakhmut, located some 50 kilometers from the frontline.

Artem Miroshnychenko was a civil activist in the “Bakhmut Ukrainian” NGO which promotes Ukrainian culture and language in the town. The NGO and Artem himself were actively engaged in volunteering for the Ukrainian army. They facilitated the provision of equipment in the initial stage of the war, then supported wounded soldiers.

Artem was beaten on the street near his home. He was thrown with his head against the sidewalk. After a serious operation and coma, Artem died on December 6.

“There was a journalistic investigation. There was a witness and her testimony. At the moment, she refuses to give her testimony again in court because she fears for her life,” says Serhiy Miroshnichenko, the brother of murdered Artem.

The unnamed woman heard the beginning of the argument when two teenagers (Mykola Barabash and Alexander Baryshok, currently arrested for the time of court hearing) clung to Artem Myroshnichenko on the street, and he answered something to them, and they asked aloud:

“Can you speak a normal language?"

After that, they started beating Artem.

While the witness refuses to testify in the local court, the lawyer and coordinator of the Public Hall of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union Alexander Kadyevskyi is asking to have the Kyiv court continue consideration of the case where the witness can feel safe.

Although all these facts are reported merely from people’s words, they perfectly reflect the atmosphere in eastern Ukrainian towns like Bakhmut, where the Ukrainian language is often perceived with caution and is not supported by local governments that several times tried to declare Russian as an official regional language as soon as Kyiv starts to abstain from language issues.

That the Kremlin considers all Russian-speakers as Russian people who constitute a single nation was often stated by Putin in a much more radical manner than recently at the Normandy summit. Answering to this constantly in the last 5 years, Ukrainian activists several times gathered for demonstrations in support of Ukrainian language when any language legislation was voted by the parliament. People brought posters with themselves where it was written: “Speak Ukrainian so that Putin will not come to protect you.”

Education law and Ukrainization of schools in Ukraine: an attempt to solve the problem

In 2017, as part of pro-Ukrainian reforms launched after the Revolution of Dignity, parliament adopted the new Education Law. Among many changes, the law stated firmly that Ukrainian is the language of instruction at schools. Although the norm is not absolutely new for Ukraine, it was not entirely implemented before. In reality, schools were able to choose the language of education, balancing between the preferred language by parents and the decisions of local authorities.

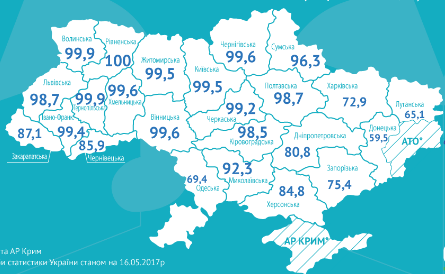

Nonetheless, throughout the whole 28-year history of independent Ukraine, the share of Russian-language schools has been decreasing steadily. In 2008 there were still 2,827 such schools in Ukraine (providing instruction for about 1/5 of all pupils). In 2015 there were 614 Russian-language schools left, while in 2019 the number decreased to only 194. Today, 92% of all pupils in Ukraine study in Ukrainian, only 7% in Russian and less than 1% in Hungarian, Polish, Romanian and Moldavian.

The number of those who would like to study Russian as a foreign or native language, additionally to Ukrainian, is also decreasing. In 1998, 39.7% believed that pupils should learn Russian as much as Ukrainian. By 2019, the number had decreased to 26.9%.

Therefore, the new law so sharply criticized by Russia and Hungary is in reality only concluding the long-time trend towards the Ukrainization of schools that started earlier. Nonetheless, Hungary is blocking any possibility for Ukraine’s membership in NATO, claiming that the Ukrainian government is discriminating against ethnic Hungarians.

Contrary to the critique, the law secures the possibility for minorities to study their native language or educate children on their native language. There are two norms in the law that should be viewed together:

- In 2020 all Russian-language schools and in 2023 all other-language schools should be transformed into Ukrainian-language schools. Studying Ukrainian is compulsory for everybody in Ukraine.

- At the same time, minorities have the right to study their native language additionally if there are enough pupils to form a group in a class. Moreover, they have the right to be educated entirely in their native language in primary schools (first 4 years, until pupils from minorities know Ukrainian sufficiently to study in it from the fifth year).

The real problem is that the rights of minorities can be realized only following the law (on the rights of minority languages) that does not exist yet. This is the critique expressed by the Venice Commission, although the commission at the same time praised the law for its promotion and equal opportunity for everyone to learn the state language. The commission in its report has also acknowledged the history of the prohibition of the Ukrainian language in the Russian empire and the Soviet Union and expressed the importance of its promotion and development.

Read also: A short guide to the “linguicide” of the Ukrainian language | Infographics

The Ukrainian Minister of Education Hanna Novosad has confirmed that since September of 2020 all Russian-language schools will be turned into Ukrainian-language ones as required by the law. However, she also confirmed that the Ministry is working on the new law on the languages of minorities in education to secure their rights properly. Also, the Ministry is working on a separate law on private schools that will allow more variety in the language of education than in state schools. When these two laws are adopted, the remarks and notes of the Venice Commission regarding the protection of minority languages are expected to be fulfilled, at least in the sphere of education.

What else can solve the language issue and unify Ukrainian identity

Read also: Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

As president Zelenskyy answered on Putin’s complaints during the Normandy summit on 9 December, everybody in Ukraine can speak any language unless it is a specific public sphere of politics, education or broadcasting. “Even today, speaking about it, I can continue in Russian” - said Zelenskyy and indeed told several sentences in Russian. That Russian is his mother tongue is not a secret. On the other hand, in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian hybrid war, this is a strong argument against Russian claims. It is much harder for Putin to continue his mantra of discrimination of Russians in Ukraine when the president of the country himself is Russian-speaking.

The laws and Ukrainization by the state policy do matter and do have an effect, as the recent successful case with music quotas proves. Yet to make the country more unified and resistant to foreign hybrid aggression, the language is probably the most important but not only and not enough tool. The task is also to unify and associate with each other regions with some differences in culture or stereotypes about each other.

For this purpose, many nationwide programs were launched in Ukraine, both by government and by civil society. Exchange programs dispel destructive myths, and bridge the east-west divide in Ukraine.

Such exchange programs are planned to be expanded in 2020. According to the new state budget, 500 million UAH are allocated for the “Unifying the Country” education project. More than 100,000 pupils will be able to travel to other regions of Ukraine in 2020 to increase their awareness of the goals of their fellow pupils, as well as their way-of-life.

Several civil initiatives, such as New Donbas or Drukarnia facilitate communication with students from different regions through creative workshops, develop civil society in Donbas around creative spaces.

The Ukrainian Leadership Academy is an exceptional project by its scale. It is implemented annually in all regions of the country. The Leadership Academy applies the system of holistic education to teach active youth during one year between school and university, making them potential changemakers.

Yellow Bus is yet another creative project that brings an information aid and cinema to the Donbas regions depressed and destroyed by war.

The list can be continued with many more projects, as well as Ukrainian films and books, more and more of which are created each year. All this just as the statistics about schools above signify that Ukraine is going to overcome regionalism that was the common political problem extensively exploited by Russia.

Read more:

- Ukraine adopts law expanding scope of Ukrainian language

- Why Ukraine’s language law is more relevant than ever

- Ukraine creates free online courses of Ukrainian language for foreigners

- Should Ukraine take over the Russian language? Scrutinizing Prof. Snyder’s arguments

- Vitaly Portnikov: the Ukrainian language is Putin’s arch-enemy

- Language policy in Ukraine and the experience of Finland and Israel