The 1910s and 1920s were a period of global transformation that was reflected in philosophy, literature, and art. People were captivated by the development of technology and the promise of future progress. Against the backdrop of new discoveries, the avant-garde movement in art emerged, with Futurism and Constructivism as the most radical. Artists everywhere expressed the desire for a complete break with the past and the creation of a "new man." The avant-garde on the territory of the Russian Empire and the early Soviet Union is often affiliated either with communist ideology or with Russian nationality. However, the reality is different. Ukrainians and their ethnic culture influenced this exciting new genre of art immensely – yet are still overlooked.

Trypillia Culture is an archaeological name for an agrarian civilization which flourished in the territory of Ukraine from 5,400 to 3,000 BCE. The Trypillia culture is especially known for its ceramic pottery. The surface of the pottery was typically decorated with inscribed ornamentation in the form of spiraling bands. Pictured: Ceramic pottery and figures from Trypillia Culture. Source: we.org.ua

Trypillia Culture is an archaeological name for an agrarian civilization which flourished in the territory of Ukraine from 5,400 to 3,000 BCE. The Trypillia culture is especially known for its ceramic pottery. The surface of the pottery was typically decorated with inscribed ornamentation in the form of spiraling bands. Pictured: Ceramic pottery and figures from Trypillia Culture. Source: we.org.ua  Known as the Balbal stone statues, dating from 4,000 BCE, hundreds of them stand on the steppe lands stretching from Ukraine to Mongolia. They are believed to have been erected by tribes of nomads as monuments of sacral art. Pictured: Stone statues at Khortytsia island on Dnipro river in southern Ukraine. Source: http://ostriv-x.blogspot.com

Known as the Balbal stone statues, dating from 4,000 BCE, hundreds of them stand on the steppe lands stretching from Ukraine to Mongolia. They are believed to have been erected by tribes of nomads as monuments of sacral art. Pictured: Stone statues at Khortytsia island on Dnipro river in southern Ukraine. Source: http://ostriv-x.blogspot.com

Avant-garde and the USSR

You have said that avant-garde artists wanted not just to create art, but also to change the world. What are the ideas through which they wanted to change the world? These ideas are commonly grouped under the term “life-affirming.” Each of these artists wanted to reveal our human nature, so that a person could actually change their life, understand the world creatively, and treat the world responsibly. Art is not just a picture that can be hung on a wall to decorate a home. Art must have a very strong influence on a person and lead them toward some form of change.

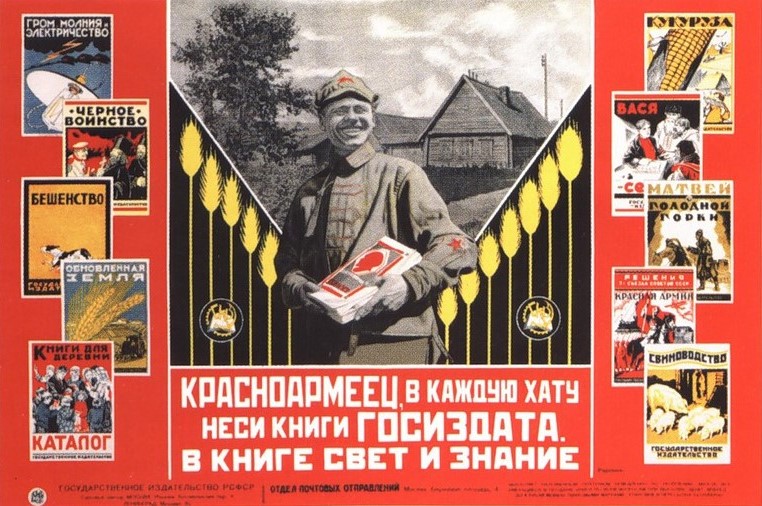

Artists "were invited" to join exhibitions devoted to the first of May (International Workers’ Day) and to paint decorations for parades and other mass events popular at that time. Those who refused, or depicted something different from the official ideology, faced repressions and forced emigration.

Kazimir Malevich, the best-known Ukrainian avant-garde artist, wrote in the 1930s: "Communism is endless hostility and a breakdown of peace and calmness, for it seeks to subjugate any thought and destroy it. No bondage knew such slavery as communism, for the life of any person here depends on his next chief."Malevich was heavily shocked by tragic events of the Soviet destruction of the Church by repressions, and by the Holodomor in the 1930s. He depicted his feelings in paintings like: The Running Man and Where Sickle and Hammer Are, there is Hunger.

Russian, Ukrainian and international avant-garde

Regarding the Ukrainian, Russian, or international avant-garde, is it possible to distinguish among them? As far as distinctions go, they probably have some validity. The avant-garde itself, in its aspirations, defined itself as an international trend – as something supra-national. It’s no accident that many avant-garde artists were enthusiasts of Esperanto [the most widely spoken artificial international auxiliary language - Ed]. They had the desire to develop a sort of universal artistic language which would tend to very simple forms – rectangles, circles, and so on. It could be open to interpretation, unlike realistic scenarios, where one must still understand history, life, context. In the avant-garde, so to speak, it was all metaphysical. As for the issue of Ukrainian or Russian: first, the very term Russian avant-garde originated because of the Russian Empire. Artists lived in the territory of the Russian Empire, therefore they were all called Russian, according to the principle of citizenship. Probably, avant-garde artists themselves would not see much of a division between the Ukrainian and Russian artists. On the other hand, we understand that any work of art is based on something. And the Ukrainian artists, who drew from their own culture, created a completely different tradition than the French or Italians. Art of any time arises from yesterday, in one way or another. It’s the result of certain traditions – it evokes responses and appeals to one’s roots. These were very strong here, in Ukraine. At our exhibition, we have centres of avant-garde shown on a map. The village of Skoptsi and the village of Verbivka are shown on par with Paris and Krakow, as well as Kyiv and other cities. Thanks to three artists – Aleksandra Ekster, Evgenia Prybylskaya, and Natalia Davydova – two new centers of avant-garde appeared on the Ukrainian map: the village of Verbivka in the Kyiv Oblast and Skoptsi in Poltava Oblast. In these villages, in 1915 -1916, peasant craftspeople were making embroidery and carpets, according to the sketches of three artists. As a result of such communication, the professionals were enriched with the colors and elements of folk art. Subsequently, the bright color range was a feature of Oleksandra Ekster's art

For more information on artists of the Ukrainian avant-garde, check out this interactive project.

Read more:

- A taste of Ukraine’s poetic Renaissance executed by Stalin

- Modernized past: how today’s Ukrainian culture combines tradition and modernity