Many events worldwide are commemorating the centenary of the Russian revolution of 1917. Most are funded by the Russian government and rarely include Ukraine in the discussion. The artistic exhibition FALLEN. Revolution --- Propaganda --- Iconoclasm in the University of Essex (UK) fills in that gap by focusing on the global relevance of Ukrainian issues, as the country recently demolished all the symbols reminding of the 1917 Revolution in its process of decommunization.

The rise and fall of Lenin

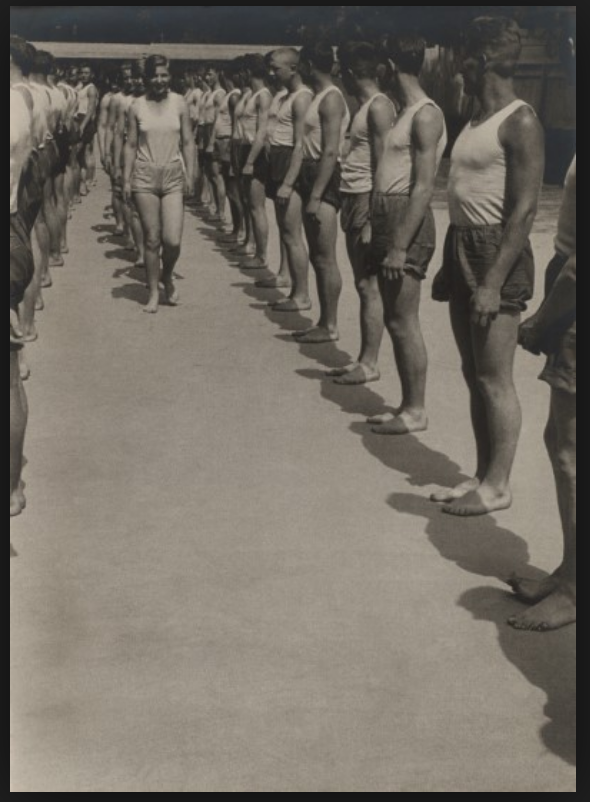

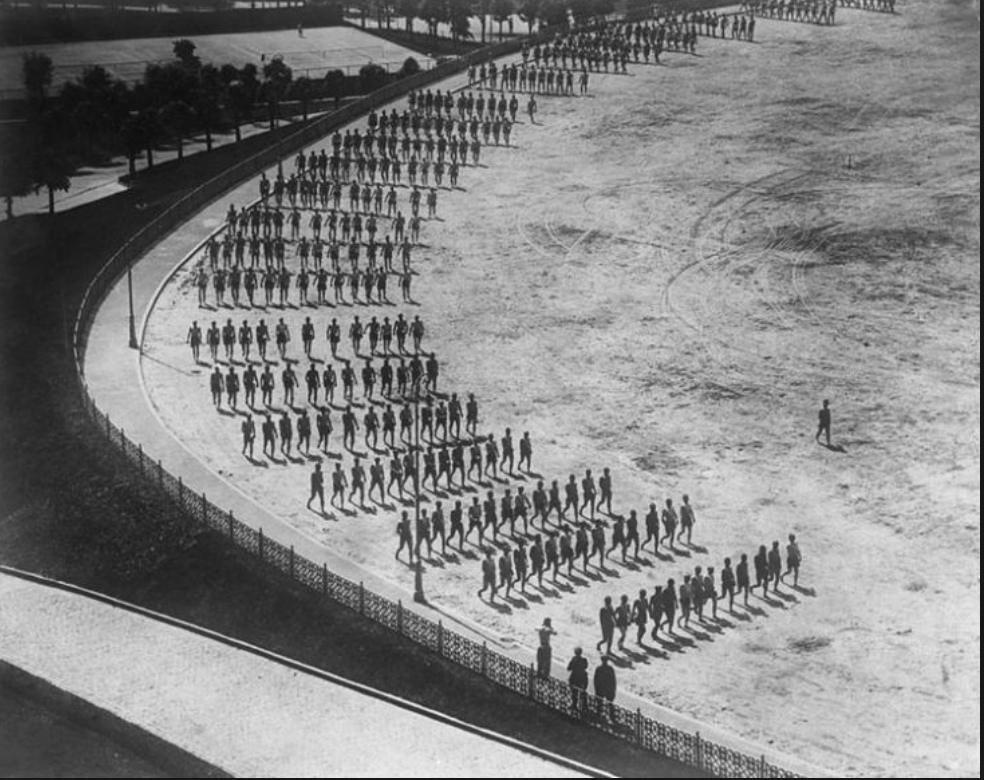

With the fall of the Russian Empire, replaced by Bolshevik Russia and the expansive Soviet Union, a revolutionary social system with ambitions to establish a new world order searched for the visual symbols to construe, and construct itself. Praise for a totalitarian system leading its faithful to a communist bright future peeked out of kindergartens and central squares. Many of the "faithful" practiced onlym superficial fidelity, accepting the official ideology for career advancement. Others believed in the Soviet utopian goals. FALLEN explores the rise and fall of the cult of Vladimir Lenin, from the exhilaration of the early Soviet years to the systematic imposition of a personality cult that was used to enforce the will of the Communist Party. The exhibition features propaganda paintings, photography, posters, and film by artists including Alexander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutsis and Sergei Eisenstein, and even a 4-meter long model of Lenin’s finger from the vast 100-meter high sculpture proposed for the Palace of the Soviets.

One hundred years later, Ukraine lived through another revolution which launched the demolition of any reminders of the old ideology. After the Euromaidan protests of 2013-2014, which finished in the ousting of Ukraine's Russian-leaning President Yanukovych and his replacement by a pro-Western government, a spontaneous "Leninfall," followed by official decommunization laws, tore down all the monuments to the communist icon in the country.

Lenin. Niels Ackermann’s photographs document the often violent act of taking down the sculptures, with some discarded near to where they fall, while others become the subject of creativity and humor, such as when Lenin is transformed into Darth Vader. Yet others are hidden away to be clandestinely venerated.

What does it mean to suddenly remove the symbols of this totalitarian ideology? And what will come to fill the empty pedestals? These are some of the questions that viewers of the exhibition FALLEN. Revolution --- Propaganda --- Iconoclasm might ask. Euromaidan Press talked to the exhibition's co-curator Myroslava Hartmond, Research Associate at the University of Oxford, UK and owner of art gallery Triptych: Global Arts Workshop in Kyiv, Ukraine to get some answers.

Euromaidan Press: Let's start with the title of the exhibition. What is an Iconoclasm?

Myroslava Hartmond: In a very wide sense, it's violence against symbols. The title of our event refers to the recent example of "Leninfall," but it also means the destruction of churches, cathedrals, Tsarist monuments etc which happened after the October revolution. The idea is to show that history comes full circle and that these things are happening today. It's a symbolism of violent destruction.

The recent "Leninfall" in Ukraine is actually the third wave of communist statue removal, a powerful image which got featured in the international media. In Ukraine, the symbols of the communist regime became associated with the regime of Yanukovych, and Lenin, who became somewhat obsolete after 25 years of Ukraine's independence from the USSR, got re-politicized, in the political context of the Revolution of Dignity, Crimean occupation, and war with Russia.

But "Leninfall" isn't something which is unique to Ukraine. Myroslava sees many parallels with the Confederate monument processes in the USA, as well as the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in South Africa and the UK. Rhodes, a British politician, state figure, and colonizer was the centerpiece of a big debate in South Africa touching upon the ethics of having statues of a racist head of state in public spaces.

What does make it unique in Ukraine, however, is the scale. In August 2017, the Head of the Institute of National Remembrance Volodymyr Viatrovych reported that in the process of official decommunization, 2389 monuments were dismantled, of them, 1320 Lenins, making Ukraine a Lenin-free zone, at least until October this year, when a monument to Lenin and Kalinin, another communist leader, were restored in the Odesa Oblast contrary to the law on decommunization.

Why is this the third wave for Ukraine? After all, the Baltic states removed all their Lenin statues shortly after independence. Myroslava says it's partially because of the sheer numbers. In 1991, Russia had some 7,000 Lenin statues. Ukraine, at a fraction of its size, had 5,500, making it the Soviet republic with the highest Lenin density. But as well, there was a lack of consensus between various governments and even local populations. Some people opposed removing Lenins.

Myroslava Hartmond: The symbolism of this statue is a separate question. Christianity has a lot of powerful images, and many Christian statues today. The exhibition is asking: is the statue obsolete? Doe the statue have space in the modern public space? As an expression of political ideology, it's getting squeezed out. It's not part of the modern city. We don't remove many statues, but we don't install many statues in the West. China and North Korea is the place where you see statues going up. The aesthetic preferences of Western liberal regimes turn towards abstraction, with public sculpture replacing political statuary.

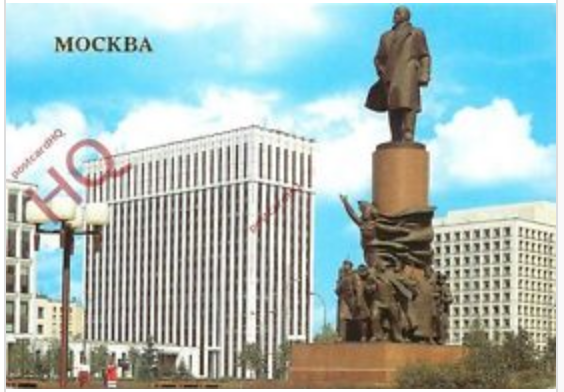

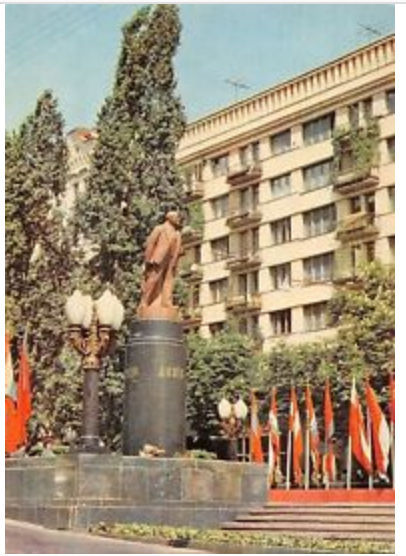

What's interesting in Soviet sculptures is that they looked back at the monumental language of the 19th century and modernized it, created an internationalist Soviet style. it established a collective Soviet identity, brought coherence to public spaces in the 15 Soviet republics, as well as satellite states. Soviet monuments were erected in Africa and Latin America and left their footprint in every public space. It was a type of cultural colonization. Of course, it's difficult to talk about colonization in Ukraine, as Ukraine a type of colony itself, being one of the Soviet republics for the longest time. So, the Baltic states had fewer statues, and more collective will to get rid of them.

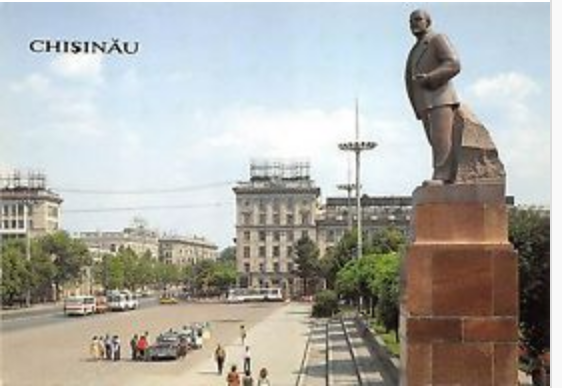

/ Postcards of Lenin statues in the former Soviet republics displayed at the exhibition:

Euromaidan Press: Are there any lessons from decommunization which Ukraine can share with the world?

Myroslava Hartmond: First and foremost, any changes to the public space should account for the will of the population. There should be some form of debate, feedback, a discussion around changes. That's something I feel was very lacking in Ukraine. The decommunization laws were passed a long time after the Lenins started falling. A lot of people didn't identify with the actions of the activists, who started tearing down the statues spontaneously, and they didn't support the laws.

Then again, it's never too late to start this debate. I feel that the discussion was absent. Then again, it shows just how little the population takes part generally in political debate. There is lots of apathy. Very few people feel that something they say would ever make a difference. So it's part of the larger problem, which can also be part of the longer legacy of disenchantment with politics. The fact that so many Lenins were left standing shows the passivity of local administrations.

I cannot help but feel that a part of Lenin's longevity in Ukraine was due to, frankly, Lenin himself. As it was the totalitarian system that established which exterminated any activity of the population for generations ahead. In the USSR, the Gulag served as a home for the politically active. 26 years after the fall of the Soviet system, political passivity still plagues Ukraine.

Related:

- Series of events in London will mark centenary of Ukrainian Revolution of 1917

- Ukraine remembers 100 years of revolution

- The Ukrainian Revolution of 1917 and why it matters for historians of the Russian revolution(s)

- Can America look to Ukraine for guidance on their growing monument problem?

- Ukraine’s European integration impossible without decommunization

- The real clash of civilizations: Last Lenin comes down in Kyiv as Stalin cult rises in Moscow

- Lenin statues to stand in Russia, but to fall in its successor states, Shtepa says

- Toppling of Lenin Monument in Kyiv Spurs ‘Monument Showers’ in Ukraine

- “Leninopad” (“Falling Lenins”) Tonight in Ukraine

- Kharkiv says good bye to largest Lenin statue in Ukraine

- Ten myths about decommunization in Ukraine

- Here’s how Kyiv’s subway would look like with Nazi symbols instead of Soviet ones

- Whose names disappeared from the map of Ukraine? Interactive decommunization map

- Ukraine’s European integration impossible without decommunization