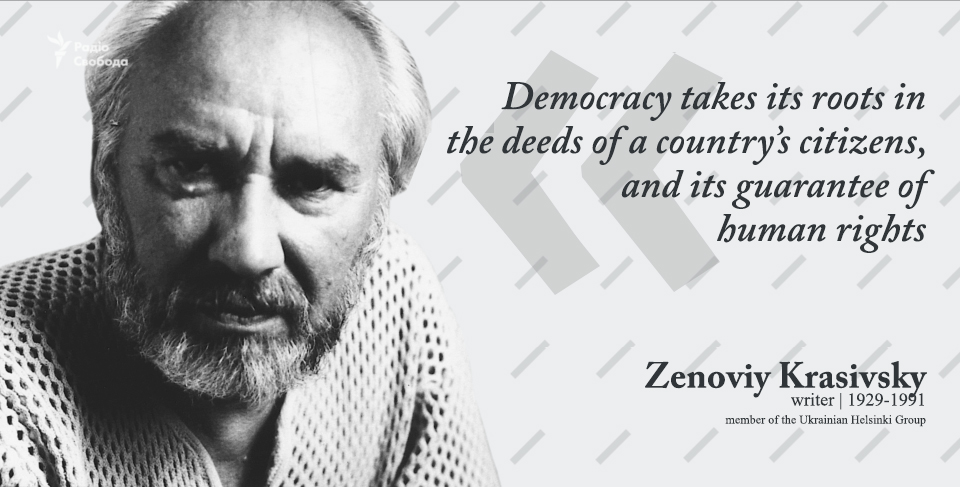

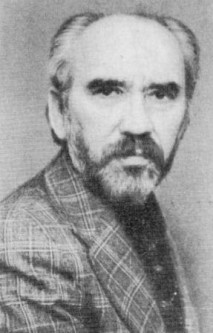

Friend and dissident Yevhen Sverstyuk called him a “kind-hearted knight in an old suit of armour”. His friends called him “Zenko”, remembering his subtle sense of humor, honesty, unfeigned patriotism and nationalist sentiment, which took their source from his love for Ukraine. Those who knew Krasivsky say that he was a happy man because he had talent and a great love.

Zenoviy Krasivsky was born on 2 November 1929 in the village of Vytvytsya (western Ukraine) and raised in a patriotic peasant family. His father fought with the Sich Riflemen [military unit fighting for Ukrainian independence from 1918 – 1920-Ed.], and during his youth, he was plunged into the war waged between UPA and the Soviet NKVD.

The Krasivsky family paid dearly for their open love of Ukraine: in 1945, his elder brother shot himself so as not to fall into the hands of the NKVD, his other brother was sentenced to 20 years of hard labour in Siberia, and in 1947 Soviet authorities confiscated the family’s property, and exiled his parents to Kazakhstan.

Krasivsky managed to escape and hid in the Carpathians. During a skirmish, he was severely wounded and arrested in 1949. He was interrogated and tortured for 21 days.

Zenoviy Krasivsky spent most of the next 26 years in prisons, camps, and exile. He was forcibly interned for “treatment” in a psychiatric hospital, which dissidents say is the most difficult form of repression. But, it was in the prison mental hospital that he found love.

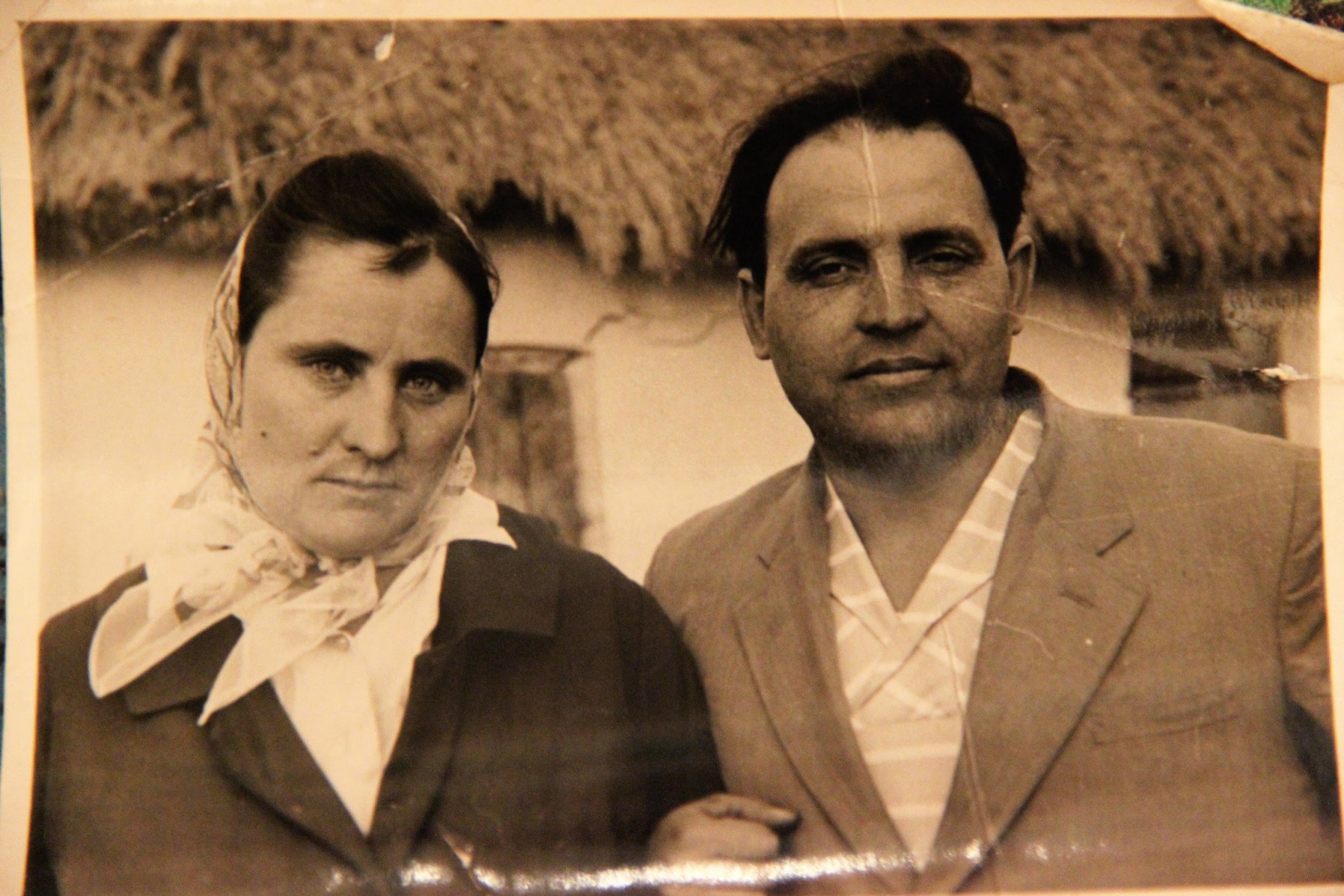

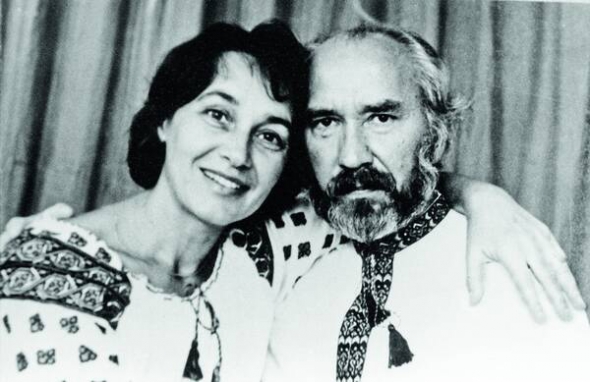

Doctor Olena Antoniv, first wife of Vyacheslav Chornovil (another member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group) met Krasivsky in a special hospital in Smolensk prison. Due to his poor condition, he was forcibly transferred to a hospital in Lviv where Olena visited him regularly. They got married as soon as he was released from hospital. Zenoviy considered that Olena was “a gift of life and love”.

In March 1980, Zenoviy Krasivsky was again arrested and sent without trial to Siberia. Olena followed him to Tyumen Oblast in Russia. They returned to Lviv in 1986.

On February 2, 1986, Olena died suddenly and tragically in a car accident. Zenoviy Krasivsky wrote the following lines in his memoirs:

“You cannot gauge my pain on a simple weight balance. The paradox of her death has entered the paradox of my life.”

Ihor Kalynets, a “Shistdesiatnyk*” (Sixties) poet recalls the Krasivsky couple:

“I saw with my own eyes how they much they loved each other, how much they respected and honoured each other. It was a true romance. Zenyk took Olena’s death very hard… It was a terrible blow...”

*(The “Shistdesiatnyky” (Sixties) movement is a literary generation that began to publish in the second half of the 1950s, and played an important role in popularizing samvydav (samizdat) literature and, most of all, in strengthening the opposition movement against Russian state chauvinism and Russification. They were completely silenced by mass arrests from 1965–72, and the movement died out at the beginning of the 1970s.-Ed.)

For ten years, Iris Akagoshi, an American member of Amnesty International, wrote to Zenoviy Krasivsky, supporting him morally and encouraging him to emigrate to the United States. However, when he was released from the psychiatric hospital, Krasivsky chose not to emigrate, and wrote the following statement when he joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group in 1979:

“I don’t consider it appropriate to say that I entered the ranks of human rights activists to vent my grievances and personal anger publicly. All my life, I’ve tried to control my anger for the enemies of my people; I’ve learned to love my people and sacrifice myself for my country. Quite early, I realized that the essence of human happiness lies not in final victory, but in our sacrifice for the ultimate ideal.”

Zenoviy Krasivsky left behind several poetry collections and correspondence. He started writing poetry in Vladimir Central Prison in Russia, and immediately gained fame and recognition in Ukrainian literary circles. His collection of poems called “Nevolnytski Plachi” (Lament in Captivity) was written in dungeons built for “enemies of the empire” under Catherine II, and was miraculously smuggled out and sent abroad. Krasivsky was punished even more severely, but his poems survived because prisoners copied and passed them from hand to hand.

In January 1991, Krasivsky spoke the following prophetic words:

“We have one historical enemy: Russia. Russia has taken everything from us. If we don’t realize this, if we don’t organize ourselves, if we don’t fight back, there will be no miracles. Our trouble is that our people have lost hope. But, an enslaved nation has no other choice. We must understand that our salvation lies in true love for our people, language, and customs.”

Time has shown that Zenoviy Krasivsky was not mistaken.