Today Ukrainians around the world commemorated the Holodomor, the terror famine Stalin directed against the peasantry in the first instance in Ukraine. But there is one nation that has never established a day to remember the victims of collectivization -- the Russians -- and the reasons for that say much about these two nations now.

On Kasparov.ru today, Moscow commentator Elena Galkina points out that unlike the Ukrainians, Russians don’t like to recall this day, “perhaps because,” she says, “constant recollection about those destroyed by the bestial state machine for its own ‘greatness’ is a medicine against slavery.”

Galkina says that she personally disagrees with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko’s characterization of the Holodomor as “a manifestation of the centuries-long hybrid war which Russia has been conducting against Ukraine.” Indeed, it was a war “but not of Russia against Ukraine but of the empire against the personality.”

In 2014, Russia became the incarnation of the imperial mindset, while Ukraine became an exemplar of the defense of the human personality, the result of divergent paths that the two peoples selected much earlier and continue to pursue.

The Soviet authorities, she writes, viewed people “as material for the construction of a powerful state” and thus took actions that “developed the main line of the Russian Empire.” That is something “the subjects of the USSR understood very well.” Many driven into the collective farms said that the initials of the CPSU stood for “the Second Serf Law of the Bolsheviks.”

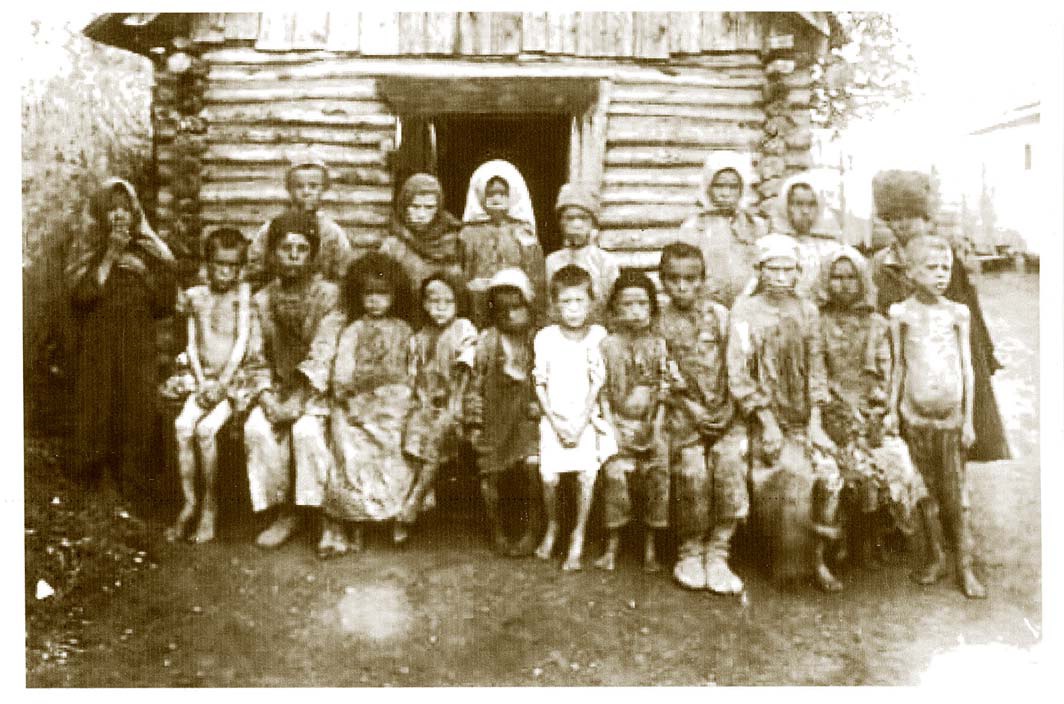

The tsarist authorities were also quite prepared to see the peasants suffer in order to sell grain abroad and promote their own goals. But the Soviets took this to a qualitatively “new level” and that lead to the deaths of millions of Ukrainians as well as of others in Kazakhstan, Belarus, and even the Russian Federation itself.

“After the collapse of the Soviet Union,” Galkina writes, “Russia had a chance to become a democratic country, but the chekist-nomenklatura elite killed it in the 1990s.” Many of its leaders viewed the people of the Russian Federation as simply cannon fodder for their favored “social-economic experiments.”

Ukraine in contrast has been able to function “without inhuman experiments on people, and as a result, its society has become many times stronger and freer than the Russian,” the Moscow commentator writes.

Emblematic of this is that “in Russia, there hasn’t been and isn’t now a day of memory for the victims of collectivization. And this is evidence of the obvious: the population of the Russian Federation remains enslaved by the empire” whose leaders don’t care about human beings but only about their own temporary power and glory.