Seventy-five years ago today, the Soviet Union began to occupy Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, act the West never recognized as legitimate but that lasted until 1991. Despite the distance in time from those events, Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite says that the Baltic peoples must remain vigilant with regard to the Russian threat.

Speaking on what in Lithuania is the Day of Mourning and Hope, Grybauskaite said that what followed the Soviet occupation in 1940 – “repressions, exiles, GULAGs, and terrible losses” – “have forever been etched in the memory of the people” and “forces us not to end our vigilance to defend our statehood and freedom.”

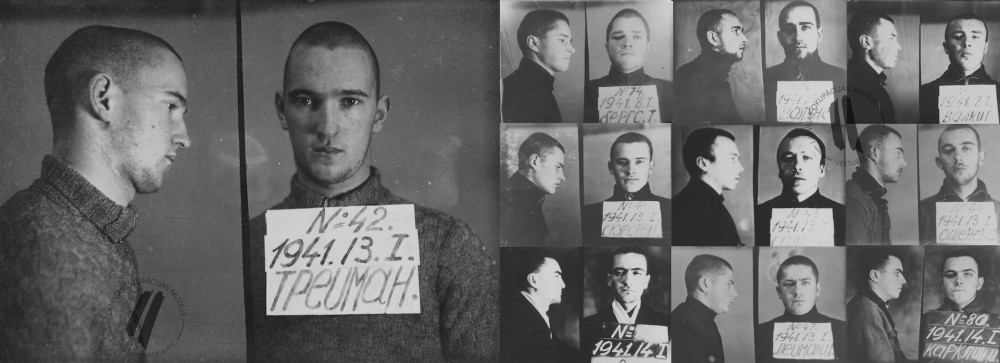

On the night of June 14, 1941, with the arrival of Soviet troops, began the first mass exiling of Lithuanians to the most distant parts of the USSR. According to the Vilnius Center on Genocide and Resistance

, in the first years of occupation alone were killed, imprisoned or exiled, about 23,000 people. By 1953, that number had risen to 280,000.

Today, in the Vilnius Cathedral in their honor was performed the premier of “Requiem in Honor of the Defenders of Freedom” and tomorrow there will be a minute of silence in their memory as well. In the coming days, similar commemorations will be held in Lithuania’s two Baltic neighbors, Estonia and Latvia.

Given the distance in time and the fog of Soviet and Russian propaganda, many have forgotten what Stalin did in 1940, have accepted Moscow’s explanations for it, and have failed to see how little has changed in the Russia modus operandi with regard to its neighbors as the world can see in the cases of Georgia and Ukraine.

In a commentary posted online today, Boris Sokolov provides a summary of what happened 75 years ago, why it was and remains illegitimate, and why the defenders of Stalin and his successors, by occupying the Baltic countries, helped set in train forces that led to the demise of the Soviet Union.

The events of June 14, 1940, are still a matter of dispute for many, the Moscow commentator says. “Many historians characterize this process as an occupation, while others call it an incorporation.” But those who deny it was an occupation fail to acknowledge that they are draining that term of all possible meaning.

“According to the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

of August 23,1939 and the Soviet-German Treaty on Friendship and Borders of September 28, 1939, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia fell in ‘the Soviet sphere of influence.’” At that time, Stalin insisted on the opening of Soviet bases in the three and the signing of mutual assistance treaties.

But the Soviet dictator did not immediately move to occupy the three, Sokolov notes. “He considered this issue in the context of a future Soviet-German war” but decided to move ahead when despite his expectations France quickly fell victim to German aggression in the late spring of 1940.

On June 8, with the fall of France clearly only a matter of days, the commentator continues, Stalin “decided to put off any attack against Hitler until 1941 and concerned himself with the occupation and annexation of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia and also took Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina from Romania.”

On June 14, Moscow presented an ultimatum to Lithuania concerning the introduction of additional Soviet troops into that country and demanding the formation of a pro-Soviet government there. “The next day, Soviet forces attacked Latvian border posts, and on June 16 similar ultimatums were presented to Latvia and Estonia.”

As Sokolov writes, “Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn recognized that resistance was hopeless and accepted the ultimatums,” although some political figures in each opposed doing so. Immediately, Moscow introduced six to nine Soviet divisions into each of the countries and used their power to demand and get the replacement of the three governments with Soviet regimes.

“In principle,” Sokolov says, “the occupation and annexation of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia in 1940 carried out by the USSR with the threat of force but without direct military actions does not differ from exactly the same ‘peaceful’ occupation by Nazi Germany of Austria in 1938, the Czech Republic in 1939, and Denmark in 1940.”

That in turn means, he argues, that not only the annexation but all the succeeding events in the three Baltic countries “up to the end of the 1980s” were “an open farce” and “illegal.”

Sokolov also notes that in the three Baltic countries, “the introduction of Soviet forces and the ensuing annexation was supported by only part of the indigenous Russian-speaking population.” It was backed by “the majority of Jews who saw in Stalin a defense against Hitler.” But “demonstrations in support of the occupation were organized with the help of Soviet forces.”

It is true,” he says that “in the Baltic countries authoritarian regimes were in place” before the Soviets came, “but these were soft regimes, and unlike the Soviets did not kill their opponents and preserved to a definite degree freedom of speech. In Estonia, for example, in 1940, there were found only 27 political prisoners.”

“The main part of the population of the Baltic countries did not support either the Soviet military occupation or in a still greater degree the liquidation of national statehood.” Instead, they formed partisan detachments – “the forest brothers” – who fought against the Soviet occupation of the Baltic countries “up to the beginning of the 1950s.”

But the Soviet occupation of the Baltic countries had an even bigger impact on the future of the USSR. Many apologists for Stalin “consider it axiomatic that Gorbachev destroyed the USSR,” according to Nikolay Klimontovich whose words Sokolov cites, “but this was done not by Gorbachev but by Stalin” when he sought to reconstitute the empire by seizing Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania among others.

That is a lesson not only for the Baltic nations and the West but also and perhaps even more for those Russians who think that Vladimir Putin is doing them a favor by invading and occupying parts of Ukraine.