Russian opposition leader Aleksey Navalny, like many others in Russia and abroad, says that referenda both past and future are the only basis for resolving the conflict over Crimea and that earlier votes in the Saarland provide a useful analogy on how to proceed.

But Russian commentator Andrey Illarionov says that Navalny and by implication others who share his confidence in a referendum as a solution in the case of Crimea are misguided and that the history they invoke is both more complicated and less positively useful than they imagine.

And he suggests that a more useful comparative case for Crimea, its current plight and its possible future, is not the two Saar referenda but rather the annexation of Eastern Pomerania and Danzig by Adolf Hitler, an action that became the trigger of Germany’s broader invasion of Poland and thus the start of World War II in Europe.

Navalny, Illarionov says, made “several mistakes,” above all about the population of Crimea, the citizenship status of its residents, and the relationship between the number of residents and the number of citizen-voters. The population of Crimea is “not three million but 2,285,000.” Not all of these people are citizens of Russia, and the share of those who could take part in a referendum is thus an inaccurate mirror of the population as a whole.

Moreover, Illarionov says, Navalny is wrong to equate the earlier Crimean referendum with the Scottish referendum on independence. “Scotland’s territory was not occupied by foreign forces,” and no one imposed the idea of a referendum on it in violation of laws. And of course, “the majority of [Scotland’s] people voted against leaving Great Britain.”

But perhaps Navalny’s biggest error – or at least the one that could have the greatest impact on the uninformed – is his suggestion that the two referenda in the Saarland (in 1935 and 1955) are appropriate models for the future of Crimea.

With regard to the first, the vote took place in “complete correspondence” with the Treaty of Versailles. No one recognized the Saar as part of France: it was under international administration. And at the time of the vote, Illarionov continues, the Saar “was not occupied by German forces,” in sharp contrast to the situation in Crimea.

With regard to the 1955 vote, “the idea of an independent Saarland state did not receive the support of the voters” and “this was interpreted as the desire of the Saar population to join West Germany.” It was not part of France, it was the subject of international negotiations, and its borders were never recognized as those between France and Germany.

“As is clear from this brief historical outline,” Illarionov says, “both Saar referenda and more generally both processes of defining the internationally recognized status of the Saar differed in principle from the operation of the conquest of Crimea by Russian forces and the forced alienation of part of the territory of an independent state in favor of the aggressor.”

As Illarionov points out, “the key distinction between the Saar methods of defining sovereignty and those employed in the Crimean case is the constant, scrupulous, and long-term application of the instruments of international law in the first case and the absolute lack of these in the second.”

“Violations, and in particular crude violations, of international law are corrected not by referenda however significant they are presented or even in fact are but by the instruments of international law,” Illarionov says; and that is something Navalny clearly does not get.

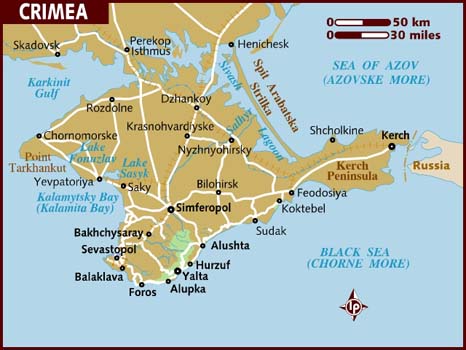

Both Eastern Pomerania and Crimea were annexed at the end of the 18th century by a major European power; both remained within them for a lengthy period; both as a result of the defeat of these powers became part of states beyond the borders of their former rulers; and both were territories that some in the former imperial centers felt properly belonged to them.

“The independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity of the two newly formed states (Poland and Ukraine) were officially recognized as the heirs of their former sovereigns (Germany and Russia); and the borders of these new states were supported by international agreements and the statutes of international organizations (the League of Nations and the UN).”

Both, Illarionov continues, were within the borders of these new states for about a generation. Both were subject to aggression from their former sovereigns, and both of these regions “were occupied and annexed by the attacking powers.” The two occupiers renamed the regions, but that was not the end of the story.

Eastern Pomerania and Danzig remained part of Germany for just under six years, after which it again became part of a restored Poland. The ethnic groups associated with the aggressor (the Germans) suffered both collectively and personally as a result. And when it was restored to Polish control, it was renamed.

These things did not happen as a result of any referendum, Illarionov points out. Rather, they came about “with the help of the instruments of international law [in the form of] the decisions of the Yalta and Potsdam conferences of the victorious powers in World War II.” He strongly implies that the ultimate fate of Crimea will be similarly decided.