My subject today is “memory of the Great Patriotic war in Russia’s expansionist policy.” I will talk in more detail about Latvia’s experience and how it conflicts with Russia’s political discourse on the Second World War. Latvia's experience acquires a new relevance in the context of Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea.

But firstly I wish to share my thoughts on why the ideologization of the Great Patriotic War is necessary for Russia’s domestic and foreign policy. Nobody denies the major role played by Russia or the USSR, in the victory over Nazism or the enormous sacrifices made to secure this victory. However, today I wish to focus on the myth of the Great Patriotic War, a myth that the Putin administration has reanimated and enhanced on a new scale since the 60th anniversary in 2005 of the end of the war.

This myth interweaves two potent narratives, that of power and of suffering

, and is a cornerstone of Russia’s identity. It is emotionally highly charged and useful for communication.

The narrative of power

The task of the myth is to argue that Russia is all-powerful and cannot be conquered. Russia is an impregnable superpower. The myth is perpetuated by the historical memory not just of the war or of the Soviet-era as a whole, but it is also fuelled by memories of Tsarist Russia. It is interesting that until the 9th of May 2014, army parades in Moscow were dominated by the Soviet symbol of the red star, but last year this was replaced by a symbol of the Tsarist era – the yellow and black colours of Saint George. The myth maintains the conviction that if the lustre of the superpower has dimmed due to some mistake of history, it must be restored, because power confers entitlement. Indisputable evidence of power is the size of conquered territory. At the start of the Second World War, after Hitler and Stalin’s pact to divide Europe, the Soviet Union expanded to the borders of 19th century Tsarist Russia. As a result of the Second World War, the Soviet Union was given unlimited power over the Baltic States, Central and Eastern Europe and a defining role in the bipolar post-war world. Putin and Russia’s spin doctors draw inspiration from memories of this imperial past. This can also be seen in Russia’s conduct in Ukraine, which Russia considers to be its backyard and not a nation and country which has a right to choose its own path and friends.

The narrative of suffering

Suffering is an equally inspiring element of the myth of the Great Patriotic War. The road to a powerful country is through suffering. It demands victims. The victims of Soviet industrialisation – millions starved and crushed in the Gulag – suffered in the name of a bright future. Stalin’s purges of the 1930s are justified by his image as a great leader who won the war. The huge human losses suffered by the Soviet army due to Stalin’s purges and incompetence are justified by victory. The suffering of the past can be transformed smoothly into a readiness to suffer in the name of the future. The Soviets learned the art of suffering. In the 1960s, Khrushchev promised overtake the USA in just a couple of years and attain communism within a generation. However, when neither goal was achieved, the Soviet people were left to suffer in the name of a brighter future. The post-soviet citizen has inherited the ability to suffer quietly, perhaps explaining why current EU and US sanctions have no impact on Putin’s popularity.

Functions of the myth

As far as Russia’s domestic policy is concerned, the myth of the Great Patriotic War serves to galvanize its people

. It is a means of reaffirming the unity of the people and the leader. Belief in Putin’s wisdom is thereby strengthened. In foreign policy, the myth is a message to the world that like during the times of Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union, Russia has a right to zones of influence. This right takes precedence over the post-war international order, because Russia is mighty and it has suffered. In regard to countries which regained their freedom as a result of what Putin considers to be the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century – the collapse of the USSR – the myth of the Great Patriotic War has another useful characteristic. It is a means of disseminating and preserving Soviet identity across borders, as well as an instrument of dividing societies in countries neighbouring Russia.

Russia wants to be a country which inspires fear and therefore respect. After the chaotic steps towards democracy in the 1990s, Russia has not made any special effort to find a new identity. The myth of the Great Patriotic War incorporates imperial pain from loss, like a body that remembers an amputated joint. This fuels resentment, which evolves into a craving for revenge and expansionism.

Rehabilitation of the Hitler–Stalin Pact of 1939

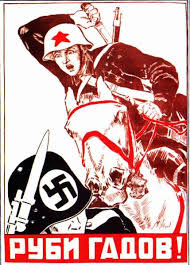

At the end of last year, Vladimir Putin broke Soviet-era silence and unveiled a new layer in the myth of the Great Patriotic War. Putin took steps towards the rehabilitation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, saying that “the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression agreement with Germany. They say, 'Oh, how bad'. But what is so bad about it, if the Soviet Union did not want to fight?” As we know from history, the Soviet Union did want to fight, and during the period from 1939 to 1941, it did so as an ally of Nazi Germany. In accordance with the borders drawn up in the secret protocols of the pact, the Soviet Union occupied the Baltic States and Bessarabia, invaded Finland, and occupied eastern Poland. Having realized the promise of the Pact, the Soviets organised a military victory parade together with the Wehrmacht. Historian Timothy Snyder, commenting upon Putin’s “what is so bad about it” statement, points out that “What is happening is an attempt by the Kremlin to move from one account of Russia in World War II to another – a shift in national historical memory that would have implications for all of Europe.” Snyder sees the implications in this shift: “As today’s Russia fights a war of aggression in Eastern Europe, the Kremlin seems increasingly ready to merge the traditional Soviet self-image as a country that defeated the Nazi aggression with Stalin’s own actions as a glorious aggressor.”

Russia’s aggression of 2008 against Georgia and its current offensive against Ukraine are evidence that the positive spin on the Hitler-Stalin Pact as part of the myth of the Great Patriotic War will become increasingly pronounced. Because once created, myths do not stay immutable. In order for them to be effective, they must absorb new political and ideological developments and requirements. Close to the heart of the Kremlin’s policies is a world divided into zones of influence, instead of a world, which, respecting the free choice of each country, is bound by international agreements. The task of the myth is to provide justification for this ideology.

[hr]Other proceedings from the conference "Usage of the topic of WWII in the Russian political discourse":

Memory of the Great Patriotic war in Russia’s expansionist policy

Occupation of Crimea repeats Latvia’s occupation by USSR

The “Great Patriotic War” as a weapon in the war against Ukraine

Russian media operates by law of war, tapping into Great Patriotic War myth

Soviet myths about World War II and their role in contemporary Russian propaganda